Scenario Overview: Employee Data Theft Investigation

What you are investigating: An employee is suspected of exfiltrating sensitive company data shortly before resigning or being terminated. The goal is to determine what data was taken, how it was taken, when it happened, and where it went, using a realistic, end-to-end lab scenario that combines Windows endpoints, removable media, email and chat, and cloud storage.

What makes this scenario different from generic “malware” cases: Data theft often uses legitimate tools and normal workflows (emailing files, syncing to cloud drives, copying to USB, printing, taking screenshots). That means you must focus on correlating multiple weak signals into a strong narrative: file access + compression + device connection + outbound transfer + account activity.

Lab deliverables: (1) a timeline of key actions, (2) a list of files/folders likely exfiltrated, (3) the suspected exfiltration channel(s), (4) supporting artifacts and screenshots, and (5) a short “executive-ready” summary of findings and confidence levels.

Lab Setup and Storyline

Characters and systems: You will investigate “Alex Kim,” a sales engineer with access to customer lists and pricing. Alex used a Windows 11 laptop (endpoint), had access to a shared file server (or SharePoint/OneDrive library), and used corporate email and chat. The security team reports unusual outbound activity and a spike in file access during Alex’s last week.

Assumptions for the lab: You have already acquired the necessary images/collections for the endpoint and relevant cloud exports. You are not re-learning acquisition or integrity steps here; instead, you will practice analysis and correlation. If you are building the lab yourself, you can simulate activity by copying a “Sensitive” folder, compressing it, and transferring it via USB and a personal cloud account.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Primary questions: Did Alex access sensitive data outside normal duties? Was it copied to removable media? Was it uploaded to personal cloud storage? Was it emailed out? Did Alex attempt to hide traces (deleting archives, clearing histories, using private browsing, renaming files)?

Investigation Plan: Hypotheses and Evidence Map

Start with hypotheses: H1: Alex copied sensitive files to a USB drive. H2: Alex uploaded files to a personal cloud account (e.g., Dropbox/Google Drive personal). H3: Alex emailed attachments to a personal address. H4: Alex used a collaboration app (Teams/Slack) or web upload. Your job is to test each hypothesis with artifacts that can confirm, refute, or narrow scope.

Build an evidence map: For each channel, list the artifacts you expect to see and what they prove. Example: for USB exfiltration, you want (a) device connection evidence, (b) file copy traces, (c) the archive or staging folder, and (d) timestamps that align. For web upload, you want (a) browser upload traces, (b) cloud client sync logs (if installed), and (c) identity/account evidence tying activity to Alex.

Define “sensitive data”: In real investigations, “sensitive” is defined by policy and business owners. In the lab, define a folder like C:\Data\Sensitive\ containing customer lists, pricing, and contracts. Create a short list of “crown jewel” filenames to search for (e.g., Customer_Master.xlsx, Pricing_2026.xlsx, TopAccounts.pptx).

Step-by-Step: Endpoint Analysis Workflow (Windows)

Step 1: Establish the user context and working days

Goal: Identify Alex’s user profile(s), typical working hours, and the “window of interest” (e.g., last 14 days). This helps you spot abnormal bursts of activity.

Actions: Enumerate user profiles, confirm the primary account used, and note time zone configuration. Identify the last logon days and any unusual after-hours sessions. Create a working timeline window (for example, from the day HR notified Alex to the termination date).

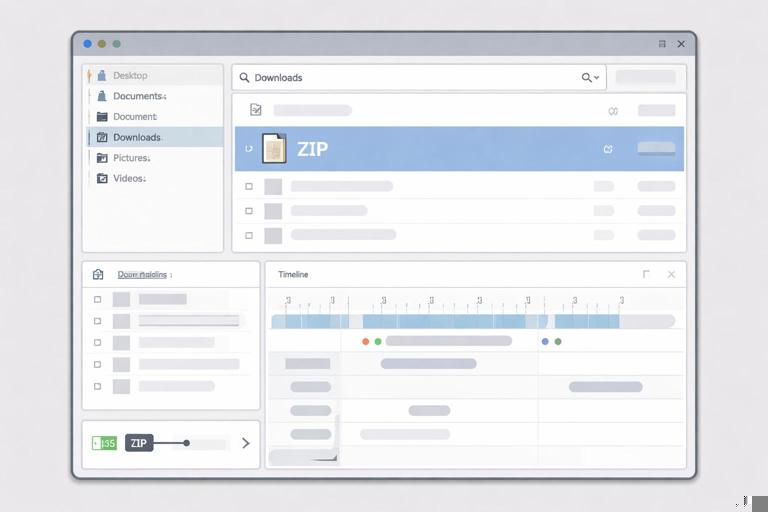

Step 2: Identify likely staging locations

Goal: Data theft often involves staging: copying files into a single folder, compressing them, then transferring. Common staging locations include Desktop, Downloads, Documents, temp folders, and cloud sync folders.

Actions: Search for recently created folders with names like “backup,” “personal,” “old,” “archive,” “transfer,” or innocuous project names. Look for large archives (.zip, .7z, .rar) and disk images (.iso). Identify “burst creation” patterns: many files created/modified within minutes.

Practical example: If you find C:\Users\Alex\Downloads\Q4_notes.zip created at 21:43, check whether many sensitive files were accessed shortly before 21:43 and whether a USB device connected around that time.

Step 3: Detect compression and packaging activity

Goal: Packaging is a strong indicator because it converts many files into one transferable object.

Actions: Look for installed archiving tools (7-Zip, WinRAR) and their recent file lists or configuration traces. Also consider built-in Windows compression (ZIP via Explorer) which may not leave “app logs” but will leave file system traces and recent item references. Identify archive filenames that resemble business content but are out of place.

What to record: Archive path, creation/modification timestamps, size, and any evidence of deletion (e.g., archive exists in Recycle Bin or is referenced but missing).

Step 4: Correlate removable media usage with file activity

Goal: Determine whether a removable drive was connected and used as a destination for copied data.

Actions: Identify connected USB storage devices and note device identifiers, volume labels, and connection times. Then look for evidence that files were accessed and copied around those times. Pay attention to “destination” hints: recent file references that point to drive letters like E:\ or volume names like SanDisk.

Practical check: If a USB device labeled BACKUP was connected at 21:50 and disconnected at 22:05, look for (a) archive creation at ~21:43, (b) file access bursts 21:30–21:45, and (c) references to E:\Q4_notes.zip or similar.

Step 5: Look for evidence of cloud sync clients and uploads

Goal: Employees often use personal cloud storage. Even if the company blocks installers, web uploads can still occur.

Actions: Check for presence of cloud sync client folders (e.g., Dropbox, Google Drive, Box) under the user profile. Review sync logs (if present) for upload events and filenames. If no client exists, pivot to browser artifacts indicating uploads to cloud services.

What to record: Account identifiers (email used to sign in), sync folder paths, log timestamps of uploads, and filenames. If you find a personal account email in a config file, that becomes an attribution anchor.

Step 6: Examine email and collaboration traces on the endpoint

Goal: Determine whether files were sent out as attachments or shared via chat.

Actions: If Outlook or another email client is used locally, look for local caches and attachment remnants. For webmail, focus on browser evidence of attachment uploads and “compose” activity. For collaboration apps, look for local caches that store downloaded or uploaded file metadata.

Practical example: A browser history entry for mail.google.com at 22:10 combined with a local file access to Q4_notes.zip at 22:08 suggests an attachment attempt, even if you cannot see the sent message content locally.

Step 7: Identify anti-forensic behavior without over-claiming

Goal: Suspects may delete archives, clear browser data, or uninstall tools. Your job is to document indicators, not assume intent.

Actions: Look for recently deleted archives in Recycle Bin, missing files referenced by recent items, sudden gaps in browser history, or uninstall traces for archiving/sync tools. Note whether system cleanup utilities ran. Correlate timing: deletion shortly after transfer is more meaningful than deletion days later.

Language discipline: Prefer “consistent with” and “suggests” unless you have direct proof. Example: “The archive was created and then deleted within 20 minutes, consistent with staging for transfer.”

Step-by-Step: Server/Share Evidence (If Applicable)

Goal: Confirm whether Alex accessed sensitive data from a shared location and whether access volume was abnormal.

Actions: Review file server access logs (or SharePoint/OneDrive access reports) for reads/downloads. Identify spikes: many files accessed in a short period, especially outside normal hours. Compare Alex’s activity to peers if you have baselines.

What to extract: File paths, timestamps, client machine name/IP (if available), and operation type (read/download). This helps prove that the sensitive data was accessed even if the endpoint lacks full traces.

Step-by-Step: Cloud and Identity Correlation (Without Re-teaching Collection)

Goal: Tie endpoint activity to cloud actions: downloads from corporate storage, uploads to personal storage, or external sharing links.

Actions: Use the exported audit logs to find events that match your endpoint timeline window. Look for: bulk downloads, creation of sharing links, external sharing invitations, and sign-ins from unusual locations or devices. Correlate with endpoint indicators such as browser sessions and local file creation.

Practical correlation pattern: If audit logs show “downloaded file” events for Pricing_2026.xlsx between 21:20–21:35 and the endpoint shows a ZIP created at 21:43 containing pricing documents, you can argue a coherent sequence: cloud download → local staging → packaging → transfer.

Timeline Construction: Turning Artifacts into a Narrative

Goal: Produce a timeline that a non-technical stakeholder can understand, while preserving technical references for validation.

Method: Build a table-like structure with columns: Time, Source, Event, Confidence, Notes. Use multiple sources per key event when possible. A single artifact can be misleading; two or three aligned artifacts are persuasive.

Example timeline entries (illustrative format) 2026-01-03 21:18 Cloud audit Alex downloaded Customer_Master.xlsx High Corporate OneDrive download 2026-01-03 21:31 Endpoint Multiple sensitive files accessed Medium Burst of file opens in Sensitive folder 2026-01-03 21:43 Endpoint Created Q4_notes.zip (2.1 GB) High Archive in Downloads 2026-01-03 21:50 Endpoint USB storage connected (label BACKUP) High Device ID/serial recorded 2026-01-03 21:52 Endpoint Reference to E:\Q4_notes.zip Medium Recent item indicates copy to USB 2026-01-03 22:07 Endpoint Q4_notes.zip deleted Medium Recycle Bin entry presentConfidence scoring: “High” when you have direct logs or multiple corroborating artifacts; “Medium” when you have indirect references; “Low” when it is plausible but uncorroborated. This prevents overstatement.

File Scoping: Determining What Was Likely Taken

Goal: Create a defensible list of files likely exfiltrated, even if you cannot recover the final transferred archive.

Approach: Start from the sensitive folder definition and identify which files were accessed during the window of interest. Then look for: (a) files included in an archive (if you can inspect it), (b) filenames referenced in recent items and application MRUs, (c) server/cloud logs showing downloads, and (d) any remnants of the archive contents.

Practical technique: If the archive is missing, use a “staging folder reconstruction” method: identify a folder created shortly before the archive, list its contents from file system metadata, and compare to the sensitive data list. If the staging folder was deleted, look for references to its path in recent items or application traces.

Attribution: Proving It Was This User on This Device

Goal: Tie actions to Alex rather than “someone on the laptop.”

Actions: Correlate interactive logons, user profile paths, and app usage under Alex’s profile. For cloud actions, tie sign-in identifiers to Alex’s corporate account. For removable media, show that the device was connected during Alex’s session. If multiple users exist on the device, explicitly rule them in or out by comparing activity windows.

Common pitfall: Assuming that because a file exists under C:\Users\Alex\, Alex created it. Instead, show that the file was created during Alex’s logged-in session and that related artifacts (recent items, app MRUs, browser sessions) also belong to Alex.

Decision Points: When to Escalate the Scope

Goal: Know when your current evidence is insufficient and what to request next (without repeating acquisition procedures).

Escalation triggers: (1) strong evidence of USB transfer but no visibility into what was copied, (2) evidence of web uploads but unclear destination account, (3) signs of external sharing links in corporate cloud, (4) indications of a second device or remote access.

What to request: Additional logs from proxy/DNS, DLP alerts, endpoint security telemetry, cloud app security logs, or the physical USB device if available. Be specific: “Need proxy logs for 21:30–22:30 on 2026-01-03 for host X to confirm uploads to drive.google.com.”

Reporting in a Data Theft Case: Structuring Findings for Stakeholders

Goal: Present findings clearly to HR, legal, and security leadership, separating facts from interpretation.

Recommended structure: (1) Allegation and scope, (2) Systems examined, (3) Key findings (bullet list), (4) Timeline of events, (5) Likely data involved (scoped list), (6) Exfiltration channels assessed (USB, email, cloud, chat) with evidence for/against each, (7) Gaps and limitations (what you could not confirm), (8) Appendices with artifact references and screenshots.

Example “key finding” phrasing: “On Jan 3 between 21:18 and 22:07, Alex’s account accessed multiple files in the Sensitive folder, created a 2.1 GB ZIP archive in Downloads, and connected a USB storage device labeled BACKUP. Artifacts indicate the ZIP was copied to the removable drive. The ZIP was later deleted from the endpoint.”