Why These Artifacts Matter: Registry, Event Logs, and Persistence

Windows investigations often hinge on three complementary sources: the Windows Registry (configuration and state), Windows Event Logs (auditable system and security events), and persistence indicators (mechanisms that make code run again after reboot or user logon). Together, they answer practical questions such as: What was configured on this host? What actions did the system record? What makes the suspicious program keep coming back? This chapter focuses on how to collect and analyze these artifacts and how to interpret them in a way that supports a defensible timeline and root-cause analysis.

Windows Registry Essentials for Examinations

What the Registry is (in forensic terms)

The Registry is a set of hierarchical databases (“hives”) that store configuration for the operating system, users, installed software, services, drivers, and many security-relevant settings. Forensics work with the Registry typically involves offline analysis of hive files copied from disk rather than live querying, because offline analysis preserves a stable snapshot and allows you to correlate timestamps and values without changes occurring during review.

Key hive files and where they live

Most investigations rely on a small set of hive files. System-wide hives are stored under C:\Windows\System32\config\ and include SAM, SYSTEM, SECURITY, and SOFTWARE. User-specific hives live in each profile directory, most commonly NTUSER.DAT and UsrClass.dat under C:\Users\<user>\ and C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\. When collecting, include the hive files and their transaction logs (for example, *.LOG1, *.LOG2) because they can contain recent changes not yet fully committed to the hive.

Registry timestamps: what they mean and what they do not

Registry keys have a “LastWrite” timestamp that updates when the key is modified (for example, a value is added, changed, or deleted). This is useful for timeline building, but it is not a direct “program executed at this time” indicator. A key’s LastWrite time can change due to legitimate system activity, software updates, group policy refresh, or user settings changes. Treat LastWrite as a “configuration changed around this time” signal and corroborate with other artifacts such as event logs and file system metadata.

Collecting Registry Hives (Practical Steps)

Step-by-step: acquire offline hive copies

When you have access to the disk (image, mounted copy, or offline volume), collect the following as a baseline: SAM, SYSTEM, SECURITY, SOFTWARE, and for each relevant user: NTUSER.DAT and UsrClass.dat. Also collect the transaction logs next to each hive. If you must collect from a live system, use built-in mechanisms that create consistent snapshots (for example, Volume Shadow Copy) or use tools that can safely copy locked files; the key is to avoid partial copies of active hives.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Step-by-step: verify you captured the right user hives

On multi-user systems, confirm which profiles exist and which are relevant. Enumerate C:\Users\ and note profile folders, then match them to SIDs in the Registry (for example, HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\ProfileList in the SOFTWARE hive) to map user names to SIDs. This mapping matters because many persistence locations are stored per-user under HKEY_USERS\<SID>\... when loaded offline.

High-Value Registry Locations for Persistence and Execution Clues

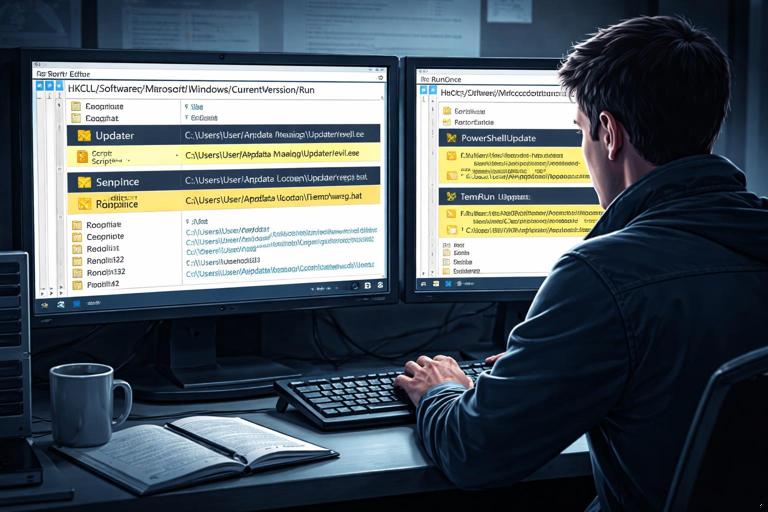

Run keys and RunOnce keys

One of the most common persistence techniques is adding a value that launches a program at user logon. Check both machine-wide and per-user locations: HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run, HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce, HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run, and HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce. In offline analysis, HKCU corresponds to the user’s NTUSER.DAT. Look for suspicious value names (random strings, masquerading as system components) and suspicious data (paths in user-writable directories, encoded commands, or use of powershell.exe, wscript.exe, mshta.exe, rundll32.exe).

Services and drivers (SYSTEM hive)

Persistent code often runs as a Windows service or driver. In the SYSTEM hive, examine HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services. Each subkey represents a service/driver and contains values such as ImagePath (what runs), Start (when it starts), and Type. Pay attention to services set to start automatically and pointing to executables in unusual locations (for example, under a user profile, temporary folders, or obscure subdirectories). Also note that CurrentControlSet is a pointer; you may need to identify which control set is active by checking Select in the SYSTEM hive.

Scheduled tasks references

Scheduled tasks are a major persistence mechanism. While task definitions are stored as files, the Registry contains supporting information. Review task-related keys such as HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Schedule\TaskCache for task names, GUIDs, and paths. Correlate Registry entries with the corresponding task files under C:\Windows\System32\Tasks\ to see the exact command line and triggers.

Winlogon and userinit shell modifications

Attackers sometimes modify logon-related values to launch additional programs. Check HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon for values like Shell and Userinit. The default Shell is typically explorer.exe, and Userinit typically points to userinit.exe (often with a trailing comma). Additional executables appended here are suspicious and should be validated against event logs and file presence.

AppInit_DLLs, Image File Execution Options, and other “special” hooks

Some persistence and execution control techniques rely on less common Registry features. AppInit_DLLs (in HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Windows) can force DLLs to load into processes, though modern protections reduce its usefulness. Image File Execution Options (IFEO) under HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Image File Execution Options can be abused with a Debugger value to hijack execution of targeted programs. When you find these, treat them as high priority because they can indicate stealthy persistence or defense evasion.

Per-user persistence beyond Run keys

Per-user persistence can hide in many places: HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Policies\Explorer\Run, HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\StartupApproved (tracks startup items approval), and application-specific auto-start settings. Also review HKCU\Software\Classes\CLSID and related COM registration areas if you suspect COM hijacking, especially when a legitimate application loads a COM object that resolves to a user-writable path.

Interpreting Suspicious Registry Data (Practical Heuristics)

Step-by-step: triage a suspicious auto-start entry

When you find a candidate persistence value (for example, a Run key entry), apply a consistent checklist: First, parse the command line carefully (quotes, arguments, environment variables). Second, resolve the path and determine whether it is user-writable or unusual for the claimed software. Third, check whether the file exists and whether there are nearby companion files (scripts, DLLs, configuration). Fourth, note the key’s LastWrite time and the value’s data, then pivot to event logs around that time to look for process creation, service installation, scheduled task registration, or logon events. Finally, look for redundancy: attackers often set multiple persistence methods so removal of one does not stop execution.

Common red flags

Red flags include: executables launched from AppData, Temp, ProgramData subfolders with random names; command lines that use -enc or long base64 strings; scripts launched by wscript/cscript; LOLBins such as rundll32 pointing to non-standard DLLs; and entries that mimic Windows components (for example, “Windows Update Service”) but point to a non-Microsoft path. A single red flag is not proof; treat it as a lead to corroborate.

Windows Event Logs Essentials

What Event Logs provide

Windows Event Logs record structured events from the OS and applications. For forensics, they can show authentication activity, service installation, task registration, policy changes, and sometimes process creation (when auditing is enabled). Event logs are especially valuable because they often contain precise timestamps, user context, and event IDs that can be correlated with Registry changes and file creation times.

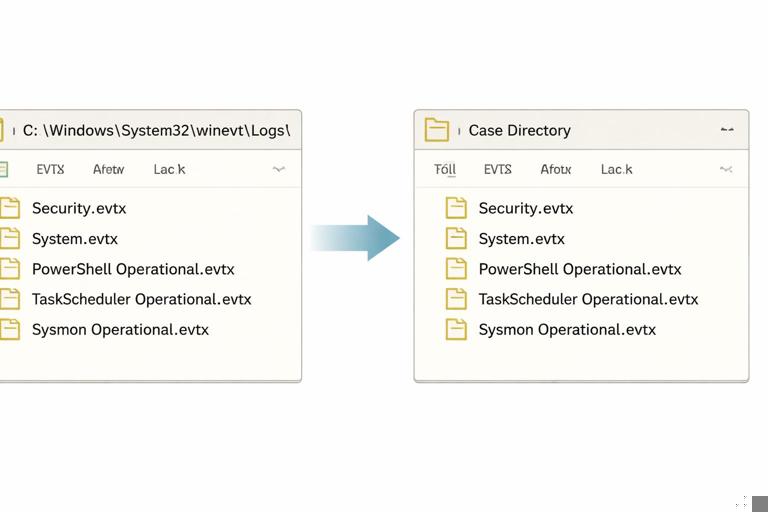

Where event logs are stored and what to collect

Event logs are stored as .evtx files under C:\Windows\System32\winevt\Logs\. Collect at least: Security.evtx, System.evtx, Application.evtx, and relevant operational logs such as Microsoft-Windows-TaskScheduler%4Operational.evtx, Microsoft-Windows-Windows Defender%4Operational.evtx, and Microsoft-Windows-PowerShell%4Operational.evtx (if present). If Sysmon is deployed, collect Microsoft-Windows-Sysmon%4Operational.evtx because it can provide detailed process, network, and file events.

Event IDs and Log Sources That Commonly Support Persistence Findings

Security log: authentication and (sometimes) process creation

The Security log can show logon activity (for example, interactive, remote, service logons) and account changes. If process creation auditing is enabled, it can record process start events with command lines. Use these events to validate whether a suspicious persistence entry actually executed and under which account. Also look for patterns such as repeated failed logons followed by a success, or logons at unusual hours that coincide with persistence installation.

System log: services, drivers, and system changes

The System log is useful for service start/stop events, driver load issues, and system boot/shutdown. If you identify a suspicious service in the Registry, the System log can help confirm when it started, whether it failed, and whether it was installed around the time of compromise. Correlate service names and image paths with Registry service keys.

Task Scheduler operational log

The Task Scheduler operational log can record task creation, updates, and execution. This is one of the best corroboration sources for scheduled task persistence because it can show when a task was registered and when it ran. When you find a suspicious task in the TaskCache Registry area or in the Tasks folder, pivot to this log to confirm activity and extract the task name and timing.

PowerShell operational log and script block logging (when enabled)

If PowerShell logging is enabled, the PowerShell operational log can reveal executed commands, module loads, and sometimes script content. This is highly relevant when persistence uses PowerShell one-liners, encoded commands, or scheduled tasks that call PowerShell. Treat these logs as sensitive and high value: they can provide direct evidence of attacker intent and tooling.

Defender and other security product logs

Windows Defender operational logs may show detections, remediation actions, exclusions added, or tamper-related events. If persistence is present but malware is missing, Defender logs can explain whether the file was quarantined or removed, leaving behind only the auto-start reference.

Working with EVTX Files (Practical Steps)

Step-by-step: export and filter events with built-in tools

You can review .evtx files using Event Viewer on an analysis workstation. Load the log file, then use filtering by Event ID, time range, and keywords (service name, task name, executable path). For command-line workflows, wevtutil can export logs and query them. For example, export a log: wevtutil epl Security C:\Case\Security.evtx. Query for a time window or event ID: wevtutil qe Security /q:"*[System[(EventID=4624)]]" /f:text /c:20. The goal is not to memorize IDs but to build repeatable filters that you apply whenever you find a persistence lead.

Step-by-step: correlate a Registry persistence timestamp to event logs

Start with the Registry key LastWrite time for the suspected persistence location (for example, a Run key or a service key). Convert it to the same time basis you are using for event logs (be mindful of time zones). Then search event logs for events within a small window around that time (for example, plus or minus 30 minutes). Look for supporting events: task registration, service installation, PowerShell execution, or logon events. If you find a matching event, extract the user, process, and command line, then pivot back to the file system to locate the referenced binary or script.

Persistence Indicators: A Structured Checklist

Common persistence categories on Windows

Persistence is broader than Run keys. Use a category-based checklist so you do not miss alternate mechanisms: logon auto-start (Run/RunOnce, Startup folder, Winlogon), services and drivers, scheduled tasks, WMI event subscriptions, COM hijacking, browser extensions, Office add-ins, and security product exclusions. Not every case requires deep review of every category, but the checklist helps you expand scope when initial leads are weak.

WMI permanent event subscriptions (concept and where to look)

WMI persistence uses event filters and consumers that trigger actions (like running a command) when a condition is met (such as user logon or a timer). This can be stealthy because it may not appear in common Run keys. Forensic review often involves examining WMI repository data and/or using tools to enumerate subscriptions on a live system. When you suspect WMI persistence, look for corroboration in event logs (WMI-Activity logs) and for unusual command lines that match other artifacts you have found.

Startup folders and “approved” startup items

In addition to Registry Run keys, Windows supports Startup folders for per-user and all-users startup. Persistence may also be reflected in “startup approved” tracking in the Registry, which can show whether an item was enabled or disabled. If you find a suspicious startup entry in the Registry, verify whether a corresponding shortcut or executable exists in Startup folders and whether it was recently created.

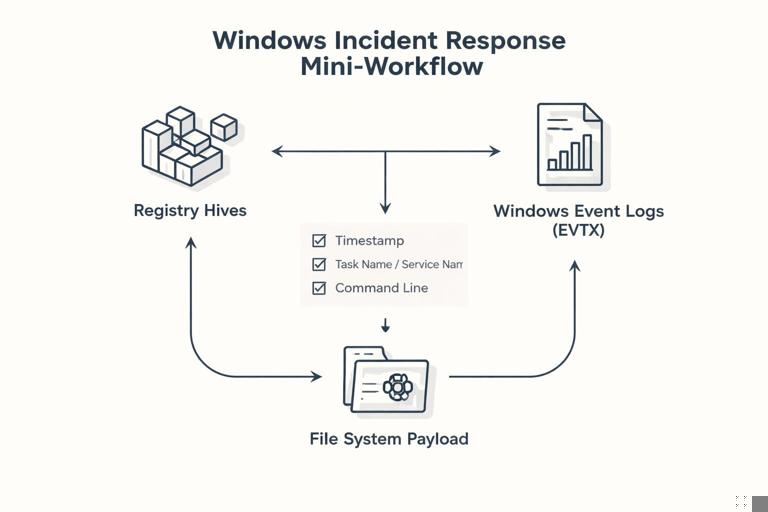

Putting It Together: A Practical Mini-Workflow

Step-by-step: from suspicious file to persistence and execution evidence

Assume you discover a suspicious executable at C:\Users\Ava\AppData\Roaming\Sync\syncsvc.exe. First, search the Registry hives for references to syncsvc.exe (Run keys, services, scheduled tasks cache, Winlogon). Second, if you find a Run key value, record the key path, value name, value data, and LastWrite time. Third, open the Task Scheduler operational log and search for the task name if tasks are involved, or open the System log if a service is involved. Fourth, check the Security log for logons around the time the persistence was created and for any process creation events that show syncsvc.exe executing. Fifth, if PowerShell is involved, search PowerShell operational logs for the same time window and for the file path. This workflow produces a chain of corroboration: configuration (Registry), recorded activity (Event Logs), and the on-disk payload (file system).

Step-by-step: from persistence entry to payload discovery

Assume you find a Run key entry that launches powershell.exe -NoP -W Hidden -enc .... First, extract and decode the encoded command in a controlled way on your analysis workstation. Second, identify any URLs, file paths, or script blocks referenced. Third, search the disk for those paths and for related artifacts (downloaded scripts, staged payloads). Fourth, pivot to PowerShell operational logs and Defender logs to see whether the script executed and whether it was detected. Fifth, check scheduled tasks and services for secondary persistence that might launch the same PowerShell command under different triggers.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Assuming one artifact is definitive

A Run key entry alone does not prove execution, and an event log entry alone may not prove persistence. Treat each artifact as a piece of a larger picture. Aim to corroborate: Registry entry plus event log evidence plus a payload on disk (or evidence it was removed).

Ignoring transaction logs and shadow copies

Registry transaction logs can contain recent changes, and older states may exist in Volume Shadow Copies. If a persistence entry appears to have been removed, you may still recover evidence of it from older hive states or transaction data. Plan collection accordingly so you can examine historical snapshots when needed.

Overlooking time normalization

Event logs, Registry LastWrite times, and file timestamps can be represented differently depending on tooling and configuration. Normalize to a consistent time zone and document the basis you used. Small time discrepancies are common; focus on correlation windows rather than exact second-level matches unless you have high-confidence synchronized sources.