What “Browser, Download, and Web Account Evidence” Means

Browser, download, and web account evidence is the collection of artifacts that describe what a user did on the web, what they retrieved from the internet, and which online identities they used. In practice, this includes browsing history, typed URLs, searches, cookies, cached content, saved form data, stored credentials, session tokens, download records, and traces of web-based applications (mail, chat, storage, social media, developer tools). These artifacts can help answer questions such as: which sites were visited, when and how often; what was searched; what files were downloaded and where they were saved; whether a user authenticated to a service; which account was used; and whether activity came from normal browsing, private mode, or an automated process.

Unlike many “single log file” sources, browser evidence is spread across multiple databases and folders, and it is heavily influenced by browser type (Chrome/Edge/Brave vs Firefox vs Safari), profile structure, sync settings, and privacy features. Modern browsers store much of their state in SQLite databases, JSON files, and LevelDB folders. Web account evidence often lives in cookies and local storage rather than in a neat “accounts list,” so you frequently infer account usage by combining multiple artifacts: a cookie value that indicates a logged-in session, a cached profile image, a saved email address in autofill, or a “last used” account identifier in site storage.

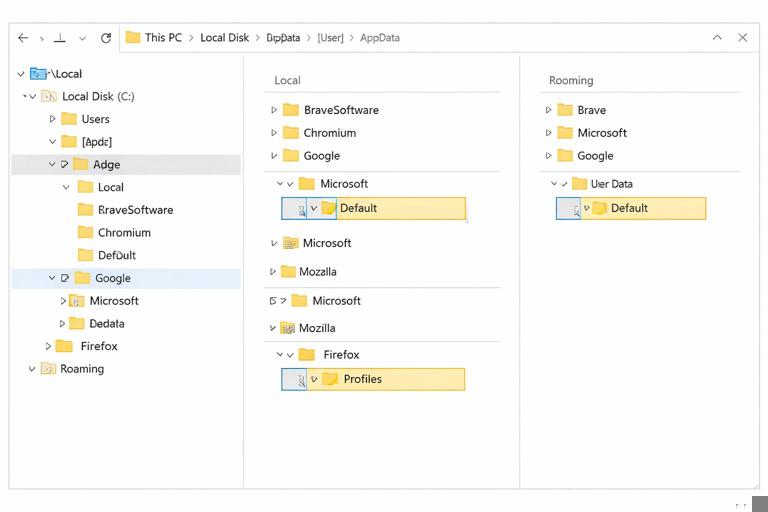

Where Browser Artifacts Live on Windows

On Windows, most browser user data is stored per-user under the user profile. The most common locations are within C:\Users\<User>\AppData\Local and C:\Users\<User>\AppData\Roaming. Chromium-based browsers (Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Brave, Opera) use a similar structure: a User Data folder containing one or more profiles (for example Default, Profile 1, Profile 2). Firefox uses a Profiles directory with randomly named profile folders (for example abcd1234.default-release).

Key Chromium paths (typical) include: ...\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\ and ...\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\Default\. Key Firefox paths include: ...\Mozilla\Firefox\Profiles\<profile>\. Within these folders you will commonly find SQLite databases like History, Cookies, Login Data, and Web Data (Chromium), and places.sqlite, cookies.sqlite, and logins.json (Firefox). You will also see folders such as Cache, Code Cache, GPUCache, and site storage folders such as Local Storage and IndexedDB.

Browser Profiles, Multiple Users, and Sync

Before interpreting any browser artifact, identify which Windows user account and which browser profile it came from. A single Windows user can have multiple browser profiles, and each profile can represent a different person or role (personal vs work) or a different set of accounts. Chromium profiles are usually named Default or Profile X, and each has its own history, cookies, and downloads. Firefox profiles are separate folders under Profiles.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Sync complicates attribution. If a browser is signed into a sync account (for example Google or Microsoft), history and passwords may be synchronized across devices. That means local artifacts can reflect activity performed elsewhere, and remote activity can appear locally after sync. Your interpretation should therefore include the question: is this evidence of activity on this machine, or evidence of data synchronized to this machine? Look for sync indicators such as account emails in browser settings files, “Signed in” state in preferences, and timestamps showing when data first appeared locally.

Core Browsing History Artifacts (Chromium and Firefox)

Browsing history answers “what URL was visited and when.” In Chromium, the primary database is History (SQLite). It contains tables that track URLs, visit counts, typed counts, referrers, and visit timestamps. In Firefox, places.sqlite stores history and bookmarks together, with tables that record visits and transitions.

Practical interpretation tips: a single URL can have multiple visits; the “last visit time” is not the only time of interest. Transition types (for example typed, link, redirect) can help you infer whether a user typed a URL, clicked a link, or was redirected. Search activity may appear as visits to search engine URLs with query parameters. Also note that browsers may prefetch or prerender pages, which can create history entries without a clear user click; correlate with other artifacts (downloads, cookies, cache, or user activity) before making strong claims.

Search Evidence and Typed Input

Search evidence often appears in URLs. For example, a Google search may include a q= parameter, Bing may include q=, and many sites embed search terms in the path. Typed URLs and omnibox entries can also be stored in browser data, depending on the browser and settings. Chromium-based browsers maintain “Top Sites” and autocomplete data that can reveal frequently accessed domains and user-entered strings.

When extracting search terms, treat them as potentially sensitive and context-dependent. A query string might reflect a user’s intent, but it might also be generated by a page script or a background request. Validate by checking whether the search URL has a corresponding visit time, whether it appears multiple times, and whether related pages were visited afterward.

Download Evidence: What Was Retrieved and Where It Went

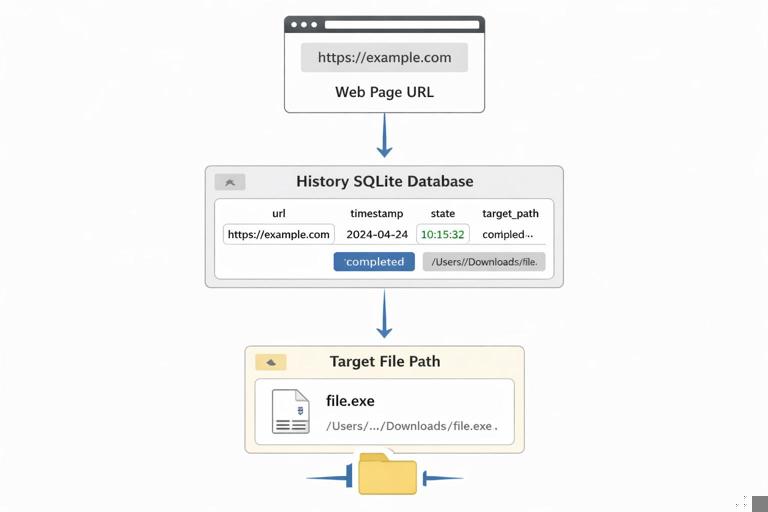

Download evidence is critical for malware cases, data theft, and policy violations. Browsers record downloads in their own databases, and the operating system may also record file creation and execution traces. In Chromium, downloads are tracked in the History database (commonly in tables related to downloads). In Firefox, download history is also represented in places.sqlite and related metadata.

Download records can include: source URL, target file path, start and end times, received bytes, total bytes, and state (completed, interrupted, canceled). They can also include a “referrer” or tab URL that initiated the download. This helps answer: did the user click a download link on a particular site, or did a background process fetch it?

Step-by-step: Extracting and Interpreting Chromium Download Records

Use this workflow when you have access to a collected browser profile folder (not live browsing). First, locate the profile folder (for example ...\Chrome\User Data\Default\). Second, copy the History SQLite database to a working directory; do not open it in-place because the browser may lock it or your tool may alter timestamps. Third, open the copied database with a SQLite viewer. Fourth, identify download-related tables and fields (commonly a downloads table plus URL chain tables). Fifth, export results to CSV for analysis and sorting.

When interpreting results, focus on: the download start time versus end time; the final target path (for example Downloads folder vs a custom path); whether the file name matches the URL; and whether the download was completed. If you see a suspicious executable downloaded but marked “interrupted,” check the file system for partial files or alternate download methods. If the download path points to removable media or a synced folder, that can be significant for exfiltration scenarios.

Step-by-step: Correlating Download Records with On-Disk Files

After you identify a download record, verify whether the file exists (or existed) on disk. First, note the target path from the download record. Second, check the directory listing in your forensic copy for the file name and size. Third, if the file is missing, look for remnants: similarly named files, temporary extensions (like .crdownload), or files in the browser cache. Fourth, correlate timestamps: the file creation/modification times should be consistent with the download end time, but be aware that copying, extraction, or antivirus actions can change them. Fifth, if the file exists, record its metadata (size, path) and plan further analysis (file type validation, malware scanning in a controlled lab, or content review depending on the case).

Cache, Stored Content, and “What Was Seen”

Browser cache can provide evidence of what content was loaded, including images, scripts, HTML, and sometimes media segments. Cache is not a perfect “what the user viewed” record, because background loads and ads can populate it. Still, it can be valuable when history is cleared or when you need to confirm that a specific resource was retrieved. Chromium uses a disk cache structure rather than a single SQLite file; Firefox also has a cache structure. You may also find cached favicons, thumbnails, and preview images.

Practical uses: confirming that a specific page resource was fetched around a time window; recovering fragments of webmail attachments or cloud storage downloads; identifying tracking pixels or beacon URLs; and demonstrating that a particular domain’s resources were repeatedly loaded. Treat cache artifacts as supporting evidence and correlate with history, cookies, and downloads.

Cookies and Session Evidence (Web Account Clues)

Cookies are one of the most important sources for web account evidence. A cookie can store a session identifier, a persistent login token, a user preference, or an account hint (such as a user ID). In Chromium, cookies are stored in a Cookies SQLite database; in Firefox, in cookies.sqlite. Cookies typically include: host/domain, name, value, path, creation time, last accessed time, expiration time, and flags such as Secure and HttpOnly.

From a forensic perspective, cookies can help you infer: which services the user logged into; which account might have been used (sometimes the cookie value or accompanying storage reveals an email or numeric account ID); and whether the session was persistent. Be careful: cookie values can be encrypted or opaque tokens, and you should avoid assuming you can “log in” with them. Your goal is usually attribution and timeline support, not session replay.

Step-by-step: Identifying Likely Logged-In Accounts from Cookies

First, list cookies for the domain of interest (for example accounts.google.com, login.microsoftonline.com, facebook.com, discord.com, amazon.com). Second, look for cookies that indicate authentication or account selection (names like SID, SSO, auth, session, token, or service-specific identifiers). Third, check creation and last accessed times to place them on a timeline. Fourth, cross-check with other artifacts: autofill entries that contain an email, cached profile images, or local storage keys that store a user identifier. Fifth, document your inference carefully: “cookies consistent with an authenticated session for service X existed and were accessed at time Y,” rather than “user definitely logged in,” unless you have stronger corroboration.

Local Storage, IndexedDB, and Web App Footprints

Modern web applications store significant data client-side using Local Storage, Session Storage, IndexedDB, and service worker caches. These can contain account identifiers, workspace IDs, recently opened documents, message snippets, or configuration data. Chromium stores these in folders such as Local Storage and IndexedDB within the profile; Firefox has similar storage under the profile directory.

These artifacts are especially valuable for SaaS tools (Slack, Teams web, webmail, project management tools) and cloud storage (Google Drive web, OneDrive web, Dropbox web). Even when the main content is server-side, the browser may store identifiers that show which tenant or account was used, which files were recently accessed, or which organizations were available in the UI.

Step-by-step: Triaging Web App Storage for Account Identifiers

First, identify the service domains involved (for example mail.google.com, outlook.office.com, drive.google.com, app.slack.com). Second, locate the corresponding storage folders in the browser profile and search for those domains in file and folder names. Third, use a specialized browser artifact tool or a structured approach: parse Local Storage records and enumerate IndexedDB databases. Fourth, search extracted values for patterns like email addresses, tenant IDs, workspace IDs, or user IDs. Fifth, validate any found identifier by checking whether the same identifier appears in cookies, history URLs, or cached API calls.

Saved Passwords, Autofill, and Form Data (Handle Carefully)

Browsers can store saved logins and autofill data, including usernames, emails, addresses, and sometimes phone numbers. Chromium stores saved logins in Login Data (SQLite) and autofill in Web Data (SQLite). Firefox stores saved logins in logins.json with encryption keys in supporting files within the profile. Access to decrypted passwords is often protected by OS-level mechanisms and may require additional steps and authorization. In many investigations, you do not need the plaintext password; the existence of a saved login for a domain and the associated username can be sufficient for account attribution.

Use these artifacts with strict scope control. Extract only what is necessary for the investigative question. For example, if the question is “which corporate account was used to access a cloud console,” the username or email in saved logins or autofill may be enough without attempting password recovery.

Private Browsing and Anti-Forensic Behaviors

Private/Incognito modes reduce local persistence of history and cookies, but they do not make activity invisible. Depending on the browser, some artifacts may still be present indirectly: DNS cache, cached certificates, downloaded files (which remain on disk), and traces in crash reports or extension logs. Additionally, users may clear history, delete downloads, or use privacy extensions. When you suspect cleaning, look for inconsistencies: missing history for a time window while cookies show recent access, or downloads that exist on disk without corresponding download records.

Also consider alternate browsers and portable browsers. A user may install a secondary browser or use a portable version stored in a user folder. Evidence may exist in less obvious locations, including non-default profiles or custom paths.

Extensions, Add-ons, and Web Account Risk

Browser extensions can store their own data and can materially affect web account evidence. Password managers, download managers, privacy blockers, and developer tools extensions may keep logs, configuration, or cached data. Extensions can also introduce exfiltration risk by accessing page content or tokens. Chromium extensions typically store data under the profile’s Extensions and extension storage areas; Firefox add-ons have their own storage within the profile.

When reviewing extensions, identify: which extensions were installed, when they were updated, and what permissions they requested. Then look for extension-specific storage that might contain account identifiers, URLs, or download tasks. This can be especially relevant when a user claims they did not download a file, but a download manager extension shows queued or automated downloads.

Cloud and Web Account Evidence: What You Can Prove Locally

Local browser artifacts can strongly suggest account usage, but they rarely provide the full server-side story. A browser can show that a user visited a cloud service, had cookies consistent with authentication, and accessed specific resource URLs. However, definitive proof of actions like “file shared externally” or “email sent” often requires server-side logs from the provider. Your local findings should be framed as: local evidence of access and interaction, plus identifiers (account email, tenant ID, session times) that can be used to request or correlate with provider logs.

Practical example: if you find visits to https://drive.google.com/drive/u/1/, cookies for google.com, and local storage containing an email address, you can infer that the user accessed Google Drive with a particular account profile. If you also find download records for a file name that matches a Drive export, you can support that a file was retrieved to disk. For actions like sharing links or deleting files, plan to corroborate with cloud audit logs if available.

Tooling Approach: Fast Triage vs Deep Parsing

For browser evidence, you typically combine two approaches. Fast triage uses artifact parsers that automatically extract history, downloads, cookies, and logins metadata into readable reports. Deep parsing uses SQLite queries and targeted extraction of storage (IndexedDB, Local Storage) when you need specific answers. Fast triage is efficient for scoping and timelines; deep parsing is necessary when you must explain exactly how you derived an account identifier or when you need to validate a suspicious URL chain.

When doing deep parsing, keep your work reproducible: note the exact file names, profile paths, and queries used; export results; and preserve the original database copies. If a database is corrupted or partially overwritten, consider using SQLite recovery techniques or carving, but treat recovered records as lower confidence unless corroborated.

Practical Mini-Lab: Build a Web Activity Narrative from a Single Profile

This mini-lab shows a structured way to turn raw browser artifacts into a narrative without over-claiming. First, identify the browser and profile folder and list key files: History, Cookies, Login Data, Web Data, and storage folders. Second, extract top visited domains and a time-bounded history around the incident window. Third, extract downloads in the same time window and list source URLs and target paths. Fourth, for the top domains, extract cookies and note creation and last accessed times. Fifth, check autofill and saved login metadata for usernames/emails that match those domains. Sixth, if the case involves a web app, inspect Local Storage and IndexedDB for account or workspace identifiers. Seventh, write findings as linked statements: “At time A, the profile visited domain X; at time B, an authenticated-session cookie for X was accessed; at time C, a file was downloaded from X to path Y.”

As you build the narrative, explicitly label confidence. A direct download record with a completed state and a matching file on disk is high confidence. A single cookie entry without corroboration is moderate. A cache entry alone is low. This disciplined approach helps you produce results that are both useful and defensible.