What “iOS Evidence” Usually Means in Practice

On iOS, “evidence” is rarely a single complete copy of the device. In most beginner-friendly and legally obtainable scenarios, you will work with logical data (what the operating system is willing to provide), iOS backups (created via Finder/iTunes or iCloud), and a limited set of on-device artifacts that can be accessed without bypassing security controls. The practical reality is shaped by iOS security design: strong hardware-backed encryption, sandboxing between apps, and privacy controls that restrict what can be extracted without the user’s passcode and explicit trust/authorization.

Because of those constraints, iOS examinations often start with questions like: Do you have the device passcode? Is the device unlocked and can it be kept unlocked? Is there an existing computer that the device already trusts? Is there an existing backup (local or iCloud)? The answers determine whether you can obtain a usable backup, which apps’ data will be included, and whether key artifacts (messages, photos, app databases, cloud tokens) are available for analysis.

Logical Extraction on iOS: What It Is and What You Actually Get

A logical extraction is a collection of data obtained through official interfaces and services (for example, Apple device services used by Finder/iTunes, configuration profiles, or app-level exports). It is not a raw copy of flash storage. Logical extraction typically yields user-visible content and structured datasets that iOS is designed to sync or back up: contacts, call history (limited), SMS/iMessage content (depending on backup type and settings), photos (depending on iCloud Photo settings), application containers (only for apps that allow backup), and device metadata.

In practice, many “logical” acquisitions are implemented as “backup-based” acquisitions: the tool triggers or reads a backup and then parses it. This is important because the backup format influences what you can parse. For example, an encrypted local backup can contain more sensitive keychain material than an unencrypted backup, which can dramatically change what you can recover (such as saved credentials or tokens for some apps).

Common iOS logical sources

- Local backups created with Finder (macOS Catalina and later) or iTunes (Windows/macOS older versions).

- iCloud backups (if credentials and access are available and policy allows collection).

- App exports (for example, exporting a chat history from within an app, or downloading account data from a service portal).

- MDM/enterprise logs and configuration data (in corporate contexts, when authorized).

Local iOS Backups: Finder/iTunes Fundamentals You Need for Forensics

A local iOS backup is a structured snapshot of device data stored on a computer. It is not a simple folder tree of the phone’s file system. Apple stores many files in a “domain + relative path” mapping, and the backup uses hashed filenames. For analysis, you typically rely on a parser (commercial or open source) to reconstruct paths and interpret databases (SQLite), property lists (plists), and media files.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Two backup modes matter for evidence: unencrypted backups and encrypted backups. Unencrypted backups are easier to create but contain less sensitive data. Encrypted backups, when you know the password, can include additional artifacts such as more complete keychain items and certain protected app data. From an investigative standpoint, an encrypted backup can be far more valuable—provided you can lawfully obtain the encryption password.

Where local backups are stored

Knowing default locations helps you identify existing backups on a suspect/user machine (when authorized) and helps you preserve the right directories for analysis.

- Windows (iTunes):

%APPDATA%\Apple Computer\MobileSync\Backup\ - macOS:

~/Library/Application Support/MobileSync/Backup/

Each device backup is stored in a folder named with a long hex string. Inside are many files with hex-like names plus metadata files such as

Manifest.dbManifest.plistInfo.plistStep-by-Step: Creating a Forensically Useful Local Backup (Finder/iTunes)

This workflow assumes you have lawful authority, the device is available, and you can interact with it. The goal is to create a backup that maximizes artifact coverage while minimizing changes and avoiding unnecessary syncing. The steps below focus on practical actions and common pitfalls.

Step 1: Prepare the workstation environment

Use a dedicated examination workstation when possible. Ensure Finder (macOS) or iTunes (Windows) is installed and up to date. Disable automatic syncing behaviors that might modify device content. In iTunes, you can reduce risk by avoiding music/photo sync operations and focusing only on “Back Up Now.” If you are using a third-party forensic tool that leverages Apple services, confirm it is configured to create a backup without altering user data.

Step 2: Connect the device and handle “Trust This Computer” prompts

When you connect an iPhone/iPad to a computer, iOS may prompt “Trust This Computer?” Accepting trust requires interaction on the device and typically the device passcode. If you cannot unlock the device, you may be blocked from creating a new backup. If the device already trusts the workstation (or a seized user computer), you may be able to proceed without additional prompts. Document whether trust was already established or newly granted, because it affects interpretation and may be relevant to later testimony.

Step 3: Choose encrypted backup when appropriate and lawful

In Finder/iTunes, select “Encrypt local backup.” You will be prompted to set a password. This password is critical: without it, you may not be able to parse protected content later. Use a controlled password management approach for the case (for example, a sealed evidence note or approved credential vault) so the password is not lost. If policy requires using a user-provided password, record how it was obtained and from whom.

Why encryption matters: encrypted backups can include more complete keychain data and other protected items. Many app tokens and saved credentials may only be present or usable when the backup is encrypted and you can decrypt it.

Step 4: Trigger “Back Up Now” and avoid extra actions

Start the backup and wait for completion. Avoid clicking “Sync” or changing content categories. If the device is set to use iCloud Photos, note that many photos may not be included in the local backup because they are stored in iCloud and only thumbnails or recent items may exist locally. Similarly, if Messages in iCloud is enabled, message content may not appear in a traditional local backup the way examiners expect; you may need to consider iCloud acquisition paths (when authorized).

Step 5: Preserve the backup folder for analysis

After the backup completes, locate the backup directory and copy the entire device backup folder (the long hex-named directory) to your case working area. Include associated metadata files. If multiple backups exist, preserve all relevant ones and note timestamps. If you are collecting from a user computer, be careful not to “clean up” old backups—older backups can contain artifacts that were later deleted from the device.

Understanding Backup Contents: What’s In, What’s Out, and Why

iOS backups are shaped by app developer choices and Apple’s data protection classes. Apps can mark files as “do not back up,” store data only in iCloud, or keep data in protected locations that require an encrypted backup to be meaningful. As a result, two backups from the same phone can differ dramatically based on settings, encryption choice, and the state of the device at backup time.

Typical artifacts you can parse from backups

Device metadata: iOS version, device name, phone number (sometimes), installed profiles, and configuration hints in

.Info.plistMessages: SMS/iMessage databases may be present depending on settings (notably Messages in iCloud). When present, they are commonly stored in SQLite databases and include message bodies, timestamps, attachments references, and chat participants.

Call history: often limited and may vary by iOS version; still useful for contact linkage and time windows.

Contacts and calendars: local address book and calendar databases, sometimes partial if primarily cloud-synced.

Photos and videos: may be partial if iCloud Photos is enabled; local camera roll items may still appear.

App data: for apps that allow backup, you may get app container files such as SQLite databases, plists, caches, and documents.

Safari artifacts: history, bookmarks, reading list, and website data may be present depending on sync settings.

Common reasons data is missing

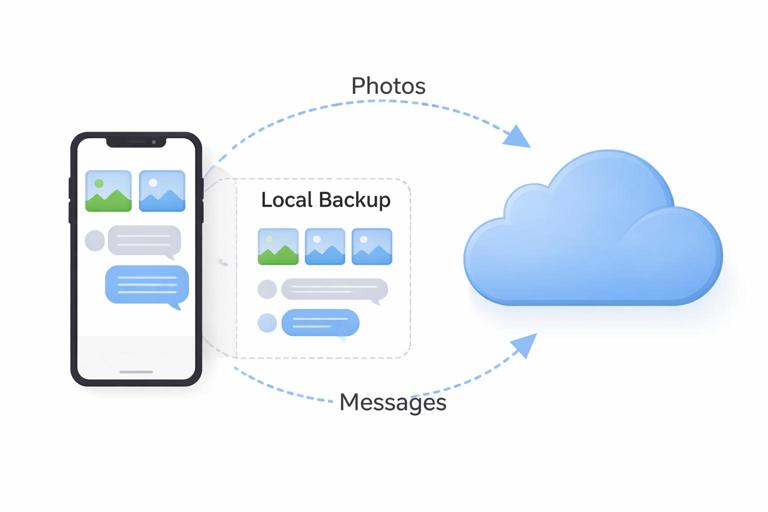

- Messages in iCloud enabled (messages stored primarily in iCloud rather than in the local backup in the expected way).

- iCloud Photos enabled (photos primarily in iCloud; local backup may not contain full-resolution originals).

- App uses “do not back up” flags or stores data in a way excluded from backups.

- Device locked state and data protection classes (some data may not be accessible unless the device has been unlocked since boot).

- Backup encryption not enabled (some protected items not included or not usable).

Manifest.db and the Hashed-Filename Problem (and How Tools Solve It)

Inside the backup folder, most files are not named like

Library/SMS/sms.dbManifest.dbManifest.dbPractical takeaway: if you copy only “interesting-looking” files out of the backup directory, you can easily lose context and miss dependencies. Preserve the entire backup folder and parse it as a unit.

iCloud Backups and Cloud-Synced Data: Practical Considerations

iCloud can hold two broad categories of evidence: iCloud device backups (snapshots similar in concept to local backups) and iCloud-synced datasets (Photos, Messages, Contacts, Notes, iCloud Drive, Safari, and app-specific iCloud storage). In many real cases, the most valuable evidence is cloud-synced rather than stored locally, especially when the device has limited storage or uses “Optimize iPhone Storage.”

Access is the main constraint. iCloud acquisition typically requires valid credentials and often a second factor (2FA). Even with credentials, Apple may prompt for approval on a trusted device or send a verification code. From a workflow perspective, you should plan for how to lawfully obtain and document authentication, and you should be prepared for partial access if 2FA cannot be satisfied.

Step-by-Step: When you have authorized iCloud access

This is a high-level workflow that avoids tool-specific instructions while highlighting the decisions you must make.

Step 1: Identify the Apple Account scope: confirm which Apple Account is used for iCloud on the device (email/phone identifier) and whether multiple accounts are involved (for example, separate accounts for App Store and iCloud).

Step 2: Determine what services are enabled: iCloud Photos, Messages, iCloud Drive, Notes, Safari, and device backups. This helps you predict where evidence lives.

Step 3: Acquire iCloud backup (if present): if an iCloud device backup exists, acquire it through an authorized method and preserve metadata such as backup date, device name, and iOS version.

Step 4: Acquire synced datasets: download iCloud Drive content, Photos libraries, Notes exports, and other service data as permitted. Preserve folder structure and timestamps as provided.

Step 5: Correlate with local backup/device artifacts: compare what appears in iCloud versus what appears in local backups. Differences can explain “missing” photos or messages.

Privacy Constraints That Shape iOS Evidence

iOS privacy constraints are not just “annoyances”; they are design features that determine what you can and cannot collect. Understanding them helps you set expectations, choose the right acquisition path, and explain limitations to stakeholders.

Passcode and Secure Enclave effects

Modern iPhones use hardware-backed encryption tied to the device passcode and the Secure Enclave. Without the passcode, you may be unable to unlock the device, approve trust prompts, or access protected data classes. Even if you have the device, many artifacts remain cryptographically inaccessible. This is why backups and cloud sources are often the primary evidence paths for beginners.

Sandboxing and per-app data boundaries

Each iOS app runs in its own sandbox. Unless the app’s data is included in backups (and not marked excluded), you may not obtain it via logical or backup extraction. Some apps store critical content in server-side accounts, meaning the device may only hold cached fragments or tokens.

“Messages in iCloud” and “iCloud Photos” as evidence movers

These settings can move the “center of gravity” for evidence away from the device and into iCloud. For example, a user may have years of iMessage history in iCloud but only a subset locally. Similarly, a device may show a full photo library in the Photos app while storing only optimized versions locally. Your acquisition plan should explicitly check for these settings and treat iCloud as a primary source when enabled and authorized.

App privacy permissions and user consent prompts

Some data (location history, health data, certain analytics) is governed by permissions and may be limited in backups. Additionally, connecting to a computer can generate prompts and logs. Be mindful that examiner actions can create new artifacts (for example, a new trust relationship), which can complicate interpretation if not documented.

Practical Analysis: Turning Backups into Usable Evidence

Once you have a backup, the next step is to extract and interpret artifacts in a repeatable way. Many iOS artifacts are stored as SQLite databases and plists. Your analysis approach should include: identifying key databases, extracting relevant tables, interpreting timestamps, and correlating across sources (messages, contacts, photos, app data). Even without deep reverse engineering, you can often answer investigative questions by focusing on a few high-value datasets.

Example workflow: Messages and attachments from a local backup

Step 1: Locate message databases via the manifest: use a parser to identify the SMS/iMessage database and related attachment directories.

Step 2: Extract chats and participants: identify conversation threads, participant identifiers (phone/email), and message direction (sent/received).

Step 3: Extract attachments: map attachment references in the database to files present in the backup. Note that some attachments may be missing if they were not stored locally at backup time.

Step 4: Validate context: correlate message timestamps with other artifacts such as photos taken around the same time or app activity logs (when available) to reduce misinterpretation.

Example workflow: App data triage from a backup

When you do not know which apps matter, triage the backup by enumerating app domains/containers and looking for common data types.

Step 1: List installed apps: use backup metadata and container listings to identify third-party apps present at backup time.

Step 2: Prioritize likely evidence apps: messaging, social media, cloud storage, finance, and navigation apps often contain high-value artifacts.

Step 3: Look for SQLite and plist files: many apps store structured data in

databases and preferences in.sqlite

. Extract and review tables for messages, contacts, transactions, or cached content..plistStep 4: Check for embedded media: app caches may contain images, videos, or documents that are not obvious from the UI.

Step 5: Note gaps caused by backup exclusions: if an app container is missing or sparse, consider whether the app opts out of backups or stores data in the cloud.

Interpreting Timestamps and Device State in iOS Artifacts

iOS artifacts can use multiple timestamp formats (Unix epoch, Mac absolute time, ISO strings) and can be stored in UTC or local time depending on the artifact. Additionally, device settings (time zone changes, automatic time, travel) can affect interpretation. When building a timeline from backup artifacts, record the device time zone settings if available in metadata and be consistent in how you normalize times during analysis.

Also consider device state: some data is only written when an app is used, when the device is charging, or when background tasks run. A backup captures a snapshot; it may not include the very latest content if it had not been committed to disk or synced at the time of backup.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Assuming a backup equals the full device

A local backup is selective. If you treat it as complete, you may incorrectly claim “no evidence exists” when the evidence is simply outside the backup scope (cloud-only, excluded by app, or protected).

Forgetting the backup password (encrypted backups)

An encrypted backup without its password can be effectively unusable for protected content. Treat the password as critical case material and store it according to your organization’s evidence handling policy.

Overlooking existing historical backups

Older backups on a user computer can contain artifacts that were later deleted from the device. When authorized to collect from a computer, look for multiple device backup folders and preserve them with their timestamps.

Misreading “missing” photos and messages

If iCloud Photos or Messages in iCloud is enabled, local backups may not contain what the user sees on the device. In such cases, iCloud acquisition (when authorized) may be the only way to obtain the full dataset.

Relying on a single artifact type

iOS evidence is often best understood by correlation: messages + photos + app logs + cloud data. If one source is incomplete, another may fill the gap.