What “Invalidated Evidence” Looks Like in Practice

Definition and impact: Evidence is “invalidated” when a judge, opposing counsel, internal review board, or incident response leadership decides it is unreliable, unauthentic, incomplete, or unfairly obtained, so it cannot be used (or is given little weight) to support a finding. In practice, invalidation often happens not because the underlying facts are wrong, but because the way the evidence was handled creates reasonable doubt about what it represents.

Common outcomes: invalidation can mean exclusion from court, inability to attribute actions to a person or device, failure to meet internal disciplinary standards, or loss of leverage in negotiations. In corporate investigations, it can also mean you cannot confidently answer “who did what, when, and how,” even if you have data.

How invalidation happens: most failures fall into a few buckets: contamination (you changed the system or data), ambiguity (you cannot explain what the artifact means), incompleteness (you missed key sources or context), and misinterpretation (you drew conclusions the data does not support). The sections below focus on concrete mistakes that cause these failures and practical ways to avoid them.

Mistake 1: Letting the System “Keep Running” and Generate New Data

What goes wrong: A live Windows machine, phone, or cloud account continues to change while you are collecting. Background updates, sync clients, antivirus scans, indexing services, and user activity can overwrite logs, rotate files, or alter timestamps. Even “just checking something” can trigger new artifacts that blur the line between suspect activity and investigator activity.

How it invalidates evidence: Opposing review can argue you cannot distinguish pre-existing artifacts from those created by your actions. This is especially damaging when the key question is timing (for example, whether a file was accessed before termination) or whether a program executed at all.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Step-by-step: Minimizing change during live handling

- Decide quickly whether you truly need live interaction: if the goal is to preserve state, avoid exploratory clicking. Use a short, pre-defined collection plan with minimal commands.

- Stabilize the environment: if policy allows, disconnect from networks to stop sync and remote changes (document the exact time and method). If you cannot disconnect, at least pause sync clients where feasible and document what you did.

- Use read-only or low-impact collection methods: prefer tools and commands known to minimize writes; avoid opening files in GUI applications that create recent-file entries and thumbnails.

- Record investigator actions in real time: keep a running activity log of every interaction (commands, clicks, windows opened), including timestamps and the rationale.

- Capture volatile priorities first: if you must collect volatile data, do it before browsing folders or launching additional applications.

Mistake 2: Using the Wrong Account, Wrong Permissions, or “Fixing” Access Problems

What goes wrong: Investigators sometimes sign in using a normal user account, a shared admin account, or an account that triggers policy changes. Others “fix” access by taking ownership of folders, resetting permissions, or enabling services. These actions can create new security events, modify ACLs, and change metadata in ways that are hard to unwind.

How it invalidates evidence: The defense (or internal audit) can argue that permission changes altered who could access what and when, or that the investigator’s account created the very access traces being used to prove misconduct.

Practical avoidance tactics

- Use a dedicated forensic/admin account with controlled scope: avoid shared credentials; ensure the account is clearly attributable to the investigator and purpose-limited.

- Do not take ownership or reset ACLs unless explicitly authorized: if access is blocked, escalate and document approval; consider alternative sources (backups, server-side logs, cloud audit) rather than altering the endpoint.

- Prefer “copy out” approaches over “open and inspect”: opening a document can change recent-file lists and application caches; copying preserves your ability to analyze offline.

- When changes are unavoidable, isolate and document them: note the exact commands, the objects changed, and the reason, and preserve before/after states where possible.

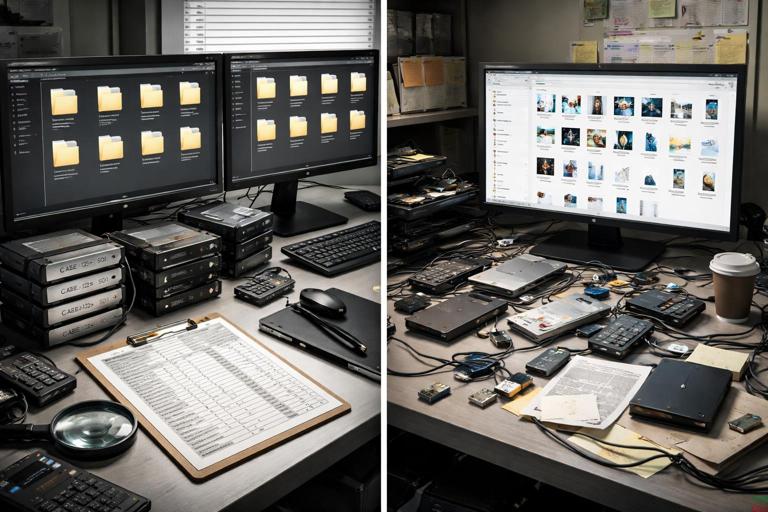

Mistake 3: Mixing Evidence from Multiple Sources Without Clear Separation

What goes wrong: Files from different machines, users, or cloud tenants get copied into a single folder, renamed inconsistently, or compressed together. Screenshots and exports are saved with generic names like “log1.csv” or “downloaded.zip.” Later, no one can tell which device or account produced which artifact.

How it invalidates evidence: If provenance is unclear, authenticity is challenged. Even if the data is accurate, you may not be able to prove it came from the claimed source, at the claimed time, under the claimed conditions.

Step-by-step: A simple separation scheme that prevents provenance loss

- Create a case folder structure that encodes source identity: for example,

CaseID/Sources/Host-WKS123/User-jdoe/andCaseID/Sources/M365-TenantA/Mailbox-jdoe/. - Use immutable source IDs: assign each source a short ID (e.g.,

S01,S02) and include it in every filename you create. - Keep raw exports separate from working copies: store raw exports in a “00_Raw” area and analysis outputs in “10_Working” so you can always return to the original export.

- Never rename inside raw folders: if you need friendly names, create a manifest (CSV) mapping original filenames to descriptive labels.

- Store screenshots with context: include the source ID, system, and timestamp in the filename (e.g.,

S01_WKS123_2026-01-07T1422Z_SecurityLogFilter.png).

Mistake 4: Relying on Screenshots as the Assured “Truth”

What goes wrong: Screenshots are easy to capture and share, so they become the primary evidence. But screenshots lack underlying data, are easy to crop or misinterpret, and often omit critical context such as filters, time ranges, and the exact query used.

How it invalidates evidence: A screenshot can be challenged as incomplete, selectively framed, or not reproducible. Without the underlying export (log file, JSON, CSV, message headers, etc.), you cannot validate the claim or re-run analysis.

Practical rule: “Screenshot plus source export”

- Always pair screenshots with the raw export: if you screenshot a portal view, also export the data behind it in the most detailed available format.

- Capture the query/filter state: screenshot the filter panel or include the query text in a note file stored alongside the export.

- Record the portal time zone and time range: many portals display local time; document what you saw and what you selected.

- Prefer machine-readable evidence for analysis: use screenshots mainly for illustrating findings, not as the only proof.

Mistake 5: Overwriting or Normalizing Timestamps During Copying and Export

What goes wrong: Some copy methods and export workflows change file timestamps, strip metadata, or repackage content. Examples include dragging files through certain interfaces, exporting emails without headers, or converting documents to PDF for “convenience.” Even well-intended “cleanup” like unzipping and rezipping can alter container metadata.

How it invalidates evidence: If timestamps are central to the narrative, altered metadata can undermine the timeline. Reviewers may argue the evidence cannot reliably show when a file existed, was modified, or was accessed.

Step-by-step: Preserving metadata during collection and handling

- Choose export formats that retain metadata: for email, include full headers; for cloud logs, export in native JSON/CSV with all fields.

- Minimize transformations: avoid converting file types; keep originals and analyze copies.

- Document the method used: note whether you used a tool export, API export, or file copy, and what that method is known to preserve or change.

- Validate critical items with secondary sources: corroborate key timestamps using independent logs (e.g., server-side access logs vs. local file metadata) when possible.

Mistake 6: Failing to Capture Context Around “Interesting” Artifacts

What goes wrong: Investigators collect only the suspicious file or a single log entry, but not the surrounding context: adjacent log lines, related configuration, or the parent record that explains meaning. For example, capturing a single audit event without the session ID, correlation ID, or the preceding authentication event can make it impossible to interpret.

How it invalidates evidence: Without context, the artifact can be ambiguous. Ambiguity is a common reason evidence is discounted: the data might be consistent with wrongdoing, but also consistent with normal operations.

Practical approach: “Collect the neighborhood”

- For logs, export a window: capture a time range before and after the event (resulting in enough surrounding entries to show sequence).

- For files, capture siblings and parents: include directory listings, related config files, and any manifest/index files that explain structure.

- For cloud events, capture correlated records: export sign-in events, token issuance, admin actions, and mailbox/file access events that share identifiers.

- Write down the hypothesis you are testing: “This event indicates a download” is different from “This event indicates a view,” and the context you need changes accordingly.

Mistake 7: Confusing “Presence” with “Action” (and “Action” with “Intent”)

What goes wrong: A file exists on disk, so the report implies it was opened. A browser history entry exists, so the report implies the user visited the site. A cloud audit event exists, so the report implies the user intentionally performed the action. These leaps are tempting, especially under time pressure.

How it invalidates evidence: Overstated conclusions are easy to attack. Many artifacts can be created by background processes, previews, sync, redirects, prefetching, or automated security tools. If your interpretation is broader than what the artifact supports, the entire analysis can be viewed as unreliable.

Practical language and validation habits

- Use precise verbs: say “was present,” “was downloaded by the browser,” “was accessed by process X,” or “an event was recorded indicating…” rather than “the user did…” unless you can attribute.

- Seek corroboration before attributing: require at least two independent indicators for high-stakes claims (e.g., assume “presence” is not “execution” without supporting traces).

- Separate technical findings from intent: intent is often a legal or HR determination; your role is to describe observable actions and supporting artifacts.

Mistake 8: Tool Output as a Black Box (Not Recording Versions, Settings, and Queries)

What goes wrong: An investigator runs a tool, exports a report, and later cannot reproduce it because the tool version changed, the parsing settings differed, or the query/filter was not saved. In cloud portals, default filters (like “last 24 hours”) can silently change what you see. In endpoint tools, parsing options can affect interpretation.

How it invalidates evidence: If results are not reproducible, they are easier to challenge. Reproducibility matters for peer review, expert testimony, and internal quality control.

Step-by-step: Making tool output reproducible

- Record tool identity: name, version, and where it was run (analyst workstation, jump box, etc.).

- Save settings and queries: export configuration files, save query text, and capture screenshots of key settings panels.

- Preserve raw inputs and raw outputs: keep the original data files and the unmodified tool exports, not just a summarized report.

- Note parsing assumptions: if the tool interprets time zones, encodings, or log schemas, document what it assumed.

Mistake 9: Cross-Contamination Through Shared Workstations, Shared USB Media, or Reused Working Directories

What goes wrong: Evidence is processed on a workstation used for multiple cases without proper separation. USB drives are reused and contain remnants from previous cases. Working directories are reused and old outputs get mixed into new ones. Even benign artifacts like temporary files can create confusion about what belongs to which case.

How it invalidates evidence: If you cannot prove that an artifact originated from the target system rather than your lab environment, it can be dismissed. Cross-contamination concerns are particularly damaging when the artifact is small (a script, a text file, a single log snippet) and could plausibly have come from anywhere.

Practical controls to prevent contamination

- Use case-dedicated working folders: never reuse a working directory; create a new one per case and per source.

- Control removable media: label media per case; avoid “general purpose” USB drives for evidence transport.

- Keep a clean analysis environment: limit background syncing (cloud drives), disable auto-indexing of evidence folders where feasible, and avoid storing evidence in user profile folders that are heavily cached.

- Generate and store a file inventory: create a manifest of files in the evidence set at the time you received it, so later additions stand out.

Mistake 10: Ignoring Locale, Encoding, and Regional Settings in Exports

What goes wrong: CSV exports use commas vs. semicolons, decimal separators differ, and date formats swap month/day. Text logs may be UTF-16 or contain non-ASCII characters. If you open and resave in a spreadsheet tool, it may silently reinterpret fields, truncate leading zeros, or convert timestamps.

How it invalidates evidence: Misparsed fields can change meanings (e.g., “03/04” becomes March 4 instead of April 3). If the exported data is altered by viewing tools, you may not be able to prove what the original said.

Step-by-step: Safe handling of structured exports

- Keep the original export untouched: store it as raw evidence and work on a copy.

- Inspect encoding before processing: use tools that show encoding and line endings; convert only copies, and document conversions.

- Parse with explicit schemas: when possible, use scripts or tools where you can specify delimiter, quote character, and date format.

- Spot-check critical fields: verify a few records against the portal view or source system to ensure parsing matches reality.

Mistake 11: Missing Data Because of Retention, Rotation, or “Default Limits”

What goes wrong: Logs rotate, cloud audit data has retention limits, and endpoints purge artifacts. Investigators sometimes assume data will be there later and delay collection, or they export only what the UI defaults to (for example, a limited date range or a maximum row count).

How it invalidates evidence: Gaps create alternative explanations. If you cannot show the full sequence of events because the middle is missing, attribution and timing become speculative.

Practical avoidance tactics

- Identify “fast-expiring” sources early: prioritize sources known to rotate quickly or be overwritten under normal use.

- Check export limits: confirm whether the portal/API paginates results, caps rows, or restricts time windows.

- Export in segments when needed: if a system limits results, export by smaller time ranges and keep a log of coverage to avoid gaps.

- Record what you could not obtain: explicitly note missing periods and the reason (retention expired, logging disabled, etc.).

Mistake 12: Treating Time as “Obvious” (Not Tracking Display Time vs. Stored Time)

What goes wrong: Even when you understand time zones conceptually, mistakes happen in practice: mixing UTC exports with local-time screenshots, forgetting that a portal displays viewer-local time, or failing to note daylight saving transitions. Analysts may also compare timestamps from different systems without aligning them to a common reference.

How it invalidates evidence: A one-hour or one-day shift can flip the narrative (before vs. after a policy change, before vs. after termination, during vs. outside business hours). If time handling is inconsistent, the timeline can be dismissed as unreliable.

Practical habit: “Time annotation on every artifact”

- Label the time basis: for each export or screenshot, note whether times are UTC, local device time, or portal-view time.

- Normalize in analysis copies: convert to a single reference time for correlation, but keep the original values in a separate column.

- Document DST boundaries when relevant: if an incident spans a DST change, explicitly call it out in notes and calculations.

Mistake 13: Over-Filtering Early and Losing Potentially Exculpatory Data

What goes wrong: Under pressure, investigators filter to only “suspicious” users, IPs, or keywords and export only those results. Later, it becomes impossible to show that you considered alternative explanations, or to demonstrate that other users/devices did not perform the same actions.

How it invalidates evidence: Selective collection can be framed as bias or cherry-picking. In some contexts, failing to preserve potentially exculpatory information can be a serious procedural problem.

Step-by-step: Balanced collection without making everything huge

- Export broad, then filter in working copies: preserve a wider time range or wider set of events as raw, then create filtered subsets for analysis.

- Keep your filter logic explicit: store the exact filter criteria in a text file and include it with the filtered dataset.

- Retain comparison baselines: when feasible, keep a small baseline sample (e.g., same event types for a non-suspect user) to support interpretation.

Mistake 14: Facilitating Remote Wipe, Account Lockout, or Evidence Destruction by Accident

What goes wrong: Actions like powering on a phone, connecting it to a network, triggering a password reset, or repeatedly attempting logins can cause remote wipe, lockouts, or security automation that deletes or quarantines data. In cloud environments, changing account states can alter logs and access patterns.

How it invalidates evidence: If evidence disappears after investigator actions, it becomes difficult to prove what existed. It can also create the appearance that the investigator caused spoliation.

Practical safeguards

- Assess risk before reconnecting devices/accounts: consider whether MDM, EDR, or conditional access policies could trigger destructive actions.

- Coordinate with administrators: if changes to accounts are needed, plan them and document who did what and when.

- Avoid repeated authentication attempts: use controlled, minimal attempts; prefer admin-side exports over interactive logins when possible.

Mistake 15: Reporting Drafts and Working Notes Becoming “Evidence” Without Control

What goes wrong: Analysts store drafts, partial interpretations, and speculative notes in shared folders or ticketing systems. Later, these drafts are discoverable in litigation or internal review and can be misread as final conclusions. Inconsistent wording between drafts and final reports can be used to attack credibility.

How it invalidates evidence: The underlying evidence may be sound, but the presentation becomes vulnerable. If your notes show uncertainty that was not resolved, or if you used imprecise language early on, it can be portrayed as unreliability.

Practical controls for notes and drafts

- Separate “analysis notes” from “findings”: keep a clearly labeled section for hypotheses and questions, and a separate section for validated statements.

- Version your report drafts: use consistent filenames and dates; avoid overwriting prior drafts without tracking changes.

- Store notes in the case repository with access control: avoid scattering notes across chat logs, personal desktops, and email threads.

- Use cautious language until validated: write “possible,” “consistent with,” and “requires corroboration” where appropriate, and update once confirmed.

Quick Reference: Mistake-to-Mitigation Map

Live system changes → Minimize interaction; document every action; stabilize network/sync behavior when allowed Wrong account/permissions → Use dedicated accounts; avoid ownership/ACL changes; escalate instead of “fixing” Mixed sources/provenance → Separate folders per source; immutable IDs; raw vs working separation Screenshot-only evidence → Pair with raw exports; capture filters/queries/time basis Timestamp/metadata alteration → Avoid transformations; choose metadata-preserving exports; corroborate key times Missing context → Collect surrounding logs/files; capture correlated records Presence ≠ action/intent → Use precise language; corroborate before attributing Black-box tool output → Record versions/settings; preserve raw inputs/outputs; save queries Cross-contamination → Case-dedicated media/folders; clean environment; manifests Locale/encoding issues → Keep raw exports; parse explicitly; spot-check critical fields Retention/rotation gaps → Prioritize expiring sources; check export limits; segment exports; note gaps Time handling inconsistencies → Annotate time basis; normalize carefully; document DST boundaries Over-filtering early → Export broad then filter; retain baselines; save filter logic Accidental destruction → Assess wipe/lockout risk; coordinate changes; avoid repeated logins Drafts/notes exposure → Separate hypotheses from findings; version drafts; controlled storage