What tokens, sessions, and cookies are (and how they relate)

Concept overview: In real systems, “authentication” usually results in the server issuing something the client can present later to prove it is the same user. That “something” can be a server-side session identifier stored in a cookie, a self-contained token (often a JWT), or a short-lived access token paired with a refresh token. The key security question is always the same: what prevents an attacker from stealing, replaying, or forging that proof?

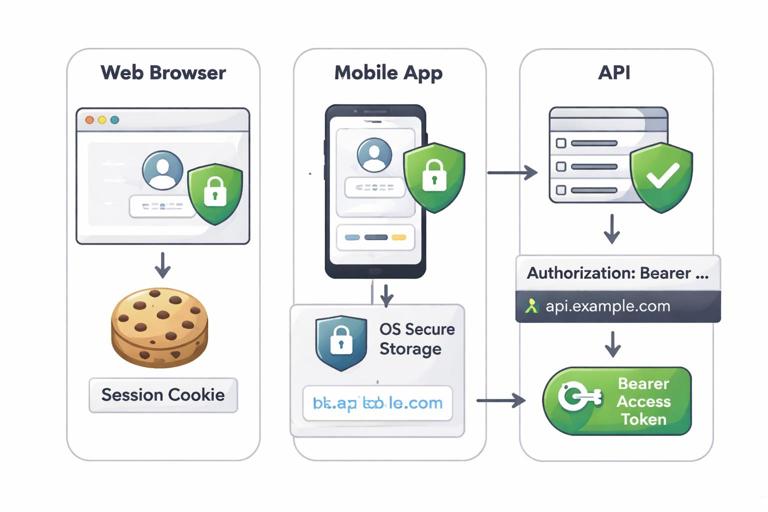

Relationship in practice: A common pattern is: the browser stores a cookie; the cookie contains either (a) a random session ID that maps to server-side state, or (b) a token value the server can validate without a database lookup. Mobile apps often store tokens in OS-protected storage and send them in an Authorization header rather than cookies. Many systems mix approaches: a cookie for browser sessions, plus bearer access tokens for APIs.

Security properties you must decide up front

Bearer vs. proof-of-possession: Most web tokens are bearer credentials: whoever holds the token can use it. That makes theft and replay the dominant risks. Proof-of-possession designs bind the token to a key held by the client (for example, mutual TLS or DPoP-style approaches), but they increase complexity and are less common in typical web apps.

Stateful vs. stateless: A server-side session is stateful: the server stores session data and can revoke it immediately. A stateless token is validated by checking its signature and claims; revocation is harder unless you add a denylist, short expirations, or token rotation. Choose based on operational needs: immediate revocation and fine-grained server control favor sessions; horizontally scaled APIs sometimes favor stateless access tokens with short lifetimes.

Browser vs. non-browser clients: Browsers have cookies, same-site rules, and CSRF risks. Non-browser clients typically use Authorization headers and face different storage and interception risks. Do not design “one token scheme” without deciding how it behaves in each client type.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Cookie fundamentals that matter for security

Cookie scope and default behavior: Cookies are automatically attached by the browser to requests matching domain/path rules. That convenience is also a risk: if a cookie is sent automatically, cross-site requests may carry it too, enabling CSRF unless you mitigate it. Cookie scope decisions (Domain, Path) also determine which subdomains and routes can read or receive the cookie.

Core cookie flags: Use cookie attributes to reduce exposure. Secure ensures cookies are only sent over HTTPS. HttpOnly prevents JavaScript from reading the cookie, reducing damage from XSS token theft (it does not prevent XSS actions). SameSite controls cross-site sending behavior: Lax is a good default for many login sessions; Strict is safer but can break some flows; None is required for third-party contexts but must be paired with Secure.

Set-Cookie: session_id=...; Path=/; Secure; HttpOnly; SameSite=LaxSession-based authentication done safely

What a “session” really is: In a classic web app, the cookie contains a random session identifier. The server stores session state keyed by that identifier: user ID, login time, CSRF token, and possibly authorization context. The security of this design depends on the session ID being unguessable and on the server treating it as a high-value secret.

Session ID handling rules: Never put meaning into the session ID (no user IDs, timestamps, or encodable data). Treat it as an opaque random value. Rotate the session ID after privilege changes (login, MFA completion, role elevation) to prevent session fixation. Expire sessions on logout and after inactivity, and consider absolute lifetimes for long-running sessions.

Step-by-step: implementing a robust session cookie

Step 1 — Create a new session on login: After verifying credentials, generate a new session record server-side and a new session ID. Store minimal necessary state: user ID, issued-at time, last-seen time, and a CSRF secret (or per-request token strategy). Avoid storing authorization decisions that can become stale if roles change; store user ID and re-check permissions as needed.

Step 2 — Set the cookie with strict attributes: Set Secure, HttpOnly, and SameSite=Lax by default for first-party web apps. Use a narrow Path if possible (for example, Path=/). Avoid Domain unless you truly need subdomain sharing; Domain=.example.com makes the cookie available to all subdomains, increasing risk if any subdomain is less trusted.

Set-Cookie: session_id=RANDOM; Path=/; Secure; HttpOnly; SameSite=Lax; Max-Age=3600Step 3 — Validate and refresh session activity: On each request, look up the session by ID, verify it exists, verify it is not expired, and update last-seen time. Consider sliding expiration (extend on activity) but also enforce an absolute expiration (for example, 24 hours) to limit long-term replay value.

Step 4 — Rotate on privilege change: When a user logs in, completes MFA, changes password, or elevates privileges, issue a new session ID and invalidate the old one. This blocks session fixation and reduces the value of a stolen pre-auth session.

Step 5 — Logout correctly: Delete server-side session state and expire the cookie client-side. Do both; expiring the cookie alone is not sufficient if an attacker already copied it.

Set-Cookie: session_id=; Path=/; Secure; HttpOnly; SameSite=Lax; Max-Age=0CSRF: why cookies make it your problem

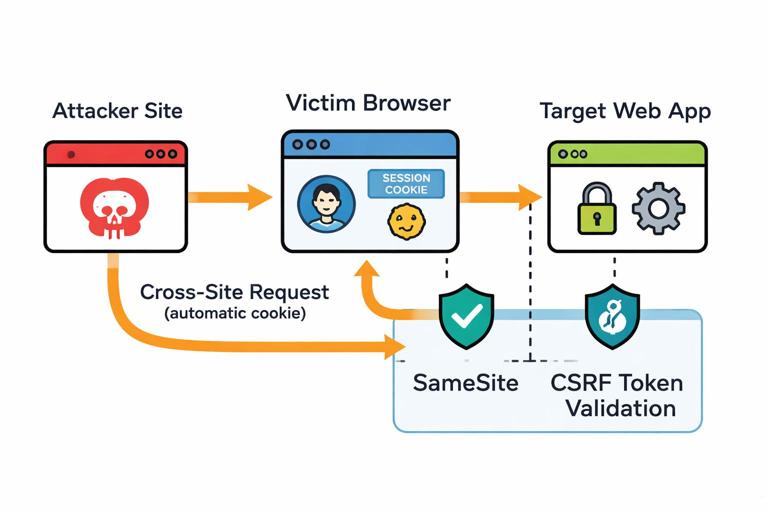

Why CSRF happens: If your authentication is cookie-based, the browser will attach the cookie automatically to cross-site requests. An attacker can trick a logged-in user into submitting a request to your site (for example, a form POST), and the browser will include the victim’s session cookie. If your server accepts that request without additional checks, the attacker can perform actions as the user.

Primary mitigations: Use SameSite cookies to reduce cross-site sending, and implement CSRF tokens for state-changing requests. SameSite=Lax blocks many cross-site POSTs but not all relevant cases (and behavior varies by flow). CSRF tokens provide explicit request authenticity: the attacker’s site cannot read the token from your site, so it cannot forge a valid request.

Step-by-step: CSRF protection that works in real apps

Step 1 — Identify state-changing endpoints: Protect POST/PUT/PATCH/DELETE and any GET endpoints that change state (avoid state changes on GET). Include sensitive actions like email change, password change, payment initiation, and API key creation.

Step 2 — Choose a token strategy: Common options include a synchronizer token stored in the server session, or a double-submit cookie pattern. If you already have server-side sessions, a synchronizer token is straightforward: store a random CSRF secret in the session and embed a derived token in forms or headers.

Step 3 — Embed token in HTML forms and AJAX: For server-rendered forms, include a hidden input. For JavaScript requests, send the token in a custom header (for example, X-CSRF-Token). Ensure the token is tied to the user session and validated server-side.

<input type="hidden" name="csrf_token" value="...">Step 4 — Validate origin signals where appropriate: For modern browsers, validating the Origin header for state-changing requests can be an additional layer. Do not rely on it as the only defense, but it can help detect obvious cross-site attempts and misconfigurations.

Token-based authentication: access tokens and refresh tokens

Access tokens: An access token is typically short-lived and presented to APIs to authorize requests. If it is a bearer token, anyone who steals it can use it until it expires. Keep access tokens short-lived to reduce replay windows, and scope them narrowly (least privilege).

Refresh tokens: Refresh tokens are longer-lived credentials used to obtain new access tokens. They are high value: if stolen, they can be used to mint fresh access tokens repeatedly. Refresh tokens require stronger storage and stronger server-side controls, such as rotation and reuse detection.

Where to store tokens in browsers: Storing bearer tokens in localStorage or sessionStorage makes them accessible to JavaScript, increasing the impact of XSS. Storing them in HttpOnly cookies reduces theft via XSS but reintroduces CSRF concerns. Many real systems choose HttpOnly cookies plus CSRF defenses for browser apps, and Authorization headers for non-browser clients.

Step-by-step: refresh token rotation with reuse detection

Step 1 — Issue a refresh token with an identifier: When the user authenticates, create a refresh token record server-side with a unique ID, user ID, device/app metadata, issued-at time, and expiration. Send the refresh token to the client (often as an HttpOnly Secure cookie for browser flows, or as a value stored in secure OS storage for mobile).

Step 2 — Rotate on every refresh: When the client uses the refresh token, invalidate it and issue a new refresh token. This limits replay: a stolen refresh token becomes useless after the legitimate client rotates it.

Step 3 — Detect reuse and respond: If an old refresh token is presented after it was rotated, treat it as a strong signal of theft. Invalidate the entire refresh token family (all tokens for that device/session) or even all sessions for the user, depending on risk tolerance. Log the event and consider step-up authentication.

Step 4 — Bind refresh tokens to context (optional but useful): You can store and compare coarse context like device ID, client type, or a stable fingerprint. Avoid brittle signals like IP address as a hard requirement (mobile networks change), but you can use them for anomaly detection.

JWTs and other self-contained tokens: common pitfalls

What “stateless” really means: A signed token like a JWT can be validated without a database lookup, but you still need server-side policy: key rotation, audience restrictions, expiration, and sometimes revocation lists. Stateless tokens reduce per-request database reads but can increase blast radius if misconfigured.

Critical validation checks: Always validate issuer (iss), audience (aud), expiration (exp), not-before (nbf) if used, and signature with the correct algorithm. Do not accept “none” algorithms. Ensure you do not accidentally accept tokens signed with an unexpected key or algorithm due to library misconfiguration.

Don’t put secrets in tokens: Even if a token is signed, its payload may be readable by clients and attackers. Only include claims you are comfortable exposing. If you need confidentiality, use an encrypted token format or keep sensitive data server-side.

Revocation strategy: If you need immediate revocation (logout everywhere, compromised account response), pure stateless access tokens are awkward. Typical approaches are: short expirations plus refresh tokens, a denylist keyed by token ID (jti), or switching to stateful sessions for browser apps.

Session fixation, hijacking, and replay: practical defenses

Session fixation: If an attacker can cause a victim to use a session ID the attacker knows (for example, by setting a cookie via a subdomain or by tricking the app into accepting a URL-provided session ID), the attacker can later reuse it. Defense: never accept session IDs from URLs, rotate session IDs on login, and scope cookies to trusted domains only.

Session hijacking: Theft can happen via XSS, malware, insecure backups, proxy logs, or accidental token exposure in URLs. Defense: HttpOnly cookies, strict transport security, avoid placing tokens in URLs, and minimize token lifetime. Also consider device/session management UI so users can revoke sessions.

Replay: Bearer tokens can be replayed until they expire or are revoked. Defense: short-lived access tokens, refresh rotation, and for high-risk operations, step-up authentication or per-request confirmation (for example, re-enter password for changing payout details).

Preventing token leakage in logs, URLs, and referrers

Keep tokens out of URLs: Query parameters and URL fragments can leak via browser history, server logs, analytics, and Referer headers. Prefer Authorization headers for APIs and cookies for browser sessions. If you must use a URL-based flow (for example, one-time email links), use single-use, short-lived tokens and ensure they are not reused as session credentials.

Log hygiene: Ensure application logs, reverse proxy logs, and error traces do not record Authorization headers, Set-Cookie values, or request bodies containing tokens. Redact sensitive headers by default and add targeted debugging that never prints raw credentials.

Referrer policy: Set a strict Referrer-Policy to reduce accidental leakage of sensitive paths. This is not a substitute for keeping tokens out of URLs, but it reduces collateral exposure.

Referrer-Policy: strict-origin-when-cross-originCookie hardening beyond the basics

Prefix cookies: Modern browsers support cookie name prefixes that enforce stronger rules. Cookies named __Host- must be Secure, must not include a Domain attribute, and must have Path=/. This helps prevent subdomain injection and cookie shadowing. Cookies named __Secure- must be Secure. Use these prefixes where possible for session cookies.

Set-Cookie: __Host-session_id=...; Path=/; Secure; HttpOnly; SameSite=LaxCookie shadowing and path confusion: If you set cookies with different paths or domains, browsers may send multiple cookies with the same name. Some server frameworks pick the “first” or “last” value inconsistently, which can be exploited. Defense: avoid duplicate cookie names, use __Host- prefix, and keep cookie scope simple.

Third-party cookies and embedded contexts: If your app must run inside an iframe or across multiple sites, you may need SameSite=None; Secure. This increases CSRF exposure, so you must rely more heavily on CSRF tokens and origin checks, and you should consider whether an embedded architecture is necessary for sensitive actions.

Designing session management for real operations

Session inventory and revocation: Provide server-side tracking of active sessions: device label, created time, last used time, and approximate location. Allow users and admins to revoke sessions. This is not only a UX feature; it is a containment tool after suspected compromise.

Idle timeout vs. absolute timeout: Idle timeouts reduce risk from unattended devices; absolute timeouts reduce risk from long-term token theft. Use both for high-value accounts. For example: idle timeout 30 minutes, absolute timeout 24 hours, with a “remember me” option that uses a separate long-lived refresh token with rotation.

Step-up authentication: For sensitive operations (changing password, adding a payment method, exporting data), require recent authentication. Implement this as a separate “recently verified” timestamp in the session and re-check it for high-risk endpoints. Do not rely on “the user has a session” as sufficient proof for every action.

Testing and verification checklist

Browser checks: Verify cookies are Secure and HttpOnly in production, and that SameSite is set intentionally. Confirm that cross-site POSTs fail without CSRF tokens. Ensure logout invalidates server sessions. Confirm that session IDs rotate on login and privilege changes.

API checks: Ensure Authorization headers are not logged. Confirm access tokens expire as expected and cannot be used after refresh rotation policies trigger revocation. Validate that token audience and issuer checks are enforced in every service that accepts tokens.

Failure-mode checks: Test what happens when clocks drift (exp/nbf), when a refresh token is reused, when multiple cookies with the same name are present, and when a user changes password (do you revoke existing sessions?). Ensure error responses do not echo token values.