What “End-to-End Encryption” Means in Practice

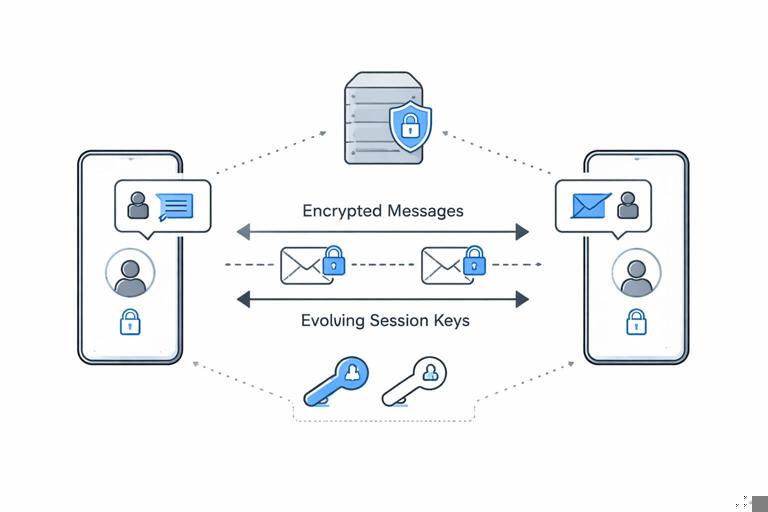

Definition and boundary: End-to-end encryption (E2EE) means message content is encrypted on the sender’s device and only decrypted on the intended recipient’s device(s). Servers may relay, queue, and fan out ciphertext, but they do not have the keys required to read plaintext. The “ends” are the user-controlled clients, not the service infrastructure.

What E2EE does and does not protect: E2EE primarily protects message content from server-side compromise, malicious insiders, and passive network observers. It does not automatically hide metadata such as who is talking to whom, when, and how often; it does not prevent endpoint compromise; and it does not guarantee that the recipient is the person you think they are unless you add authentication and verification UX.

Design goal framing: When you design E2EE, you are choosing how clients establish shared secrets, how they rotate keys, how they handle multiple devices, and how they recover from loss. Each choice affects usability, performance, and the blast radius of compromise.

Core Design Patterns for E2EE Messaging

Pattern 1: Pairwise Sessions (1:1 Chats)

Idea: Each pair of devices maintains a secure session that can encrypt and decrypt messages between them. The session can be long-lived but should evolve over time so that compromise of one key does not expose all past or future messages.

Where it fits: Direct messages, support chats, device-to-device control channels, and any scenario where a single sender talks to a single recipient device at a time.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Pattern 2: Sender Keys for Groups (Many Recipients)

Idea: Instead of encrypting the same message separately for every recipient (which is expensive), the sender uses a per-sender symmetric “sender key” for the group and distributes that key to group members via pairwise sessions. Then each group message is encrypted once with the sender key.

Tradeoff: Greatly reduces bandwidth and CPU for large groups, but changes the compromise story: if a sender key leaks, it can expose that sender’s group messages for the time window that key is valid.

Pattern 3: Per-Message Keys (Envelope Encryption at the Edge)

Idea: Generate a fresh content-encryption key (CEK) per message (or per attachment chunk), encrypt the content with the CEK, then encrypt the CEK for each recipient (or for a group sender key). This is “envelope encryption” but performed on clients.

Where it fits: Attachments, large media, and any place you want independent key rotation for content vs. session state.

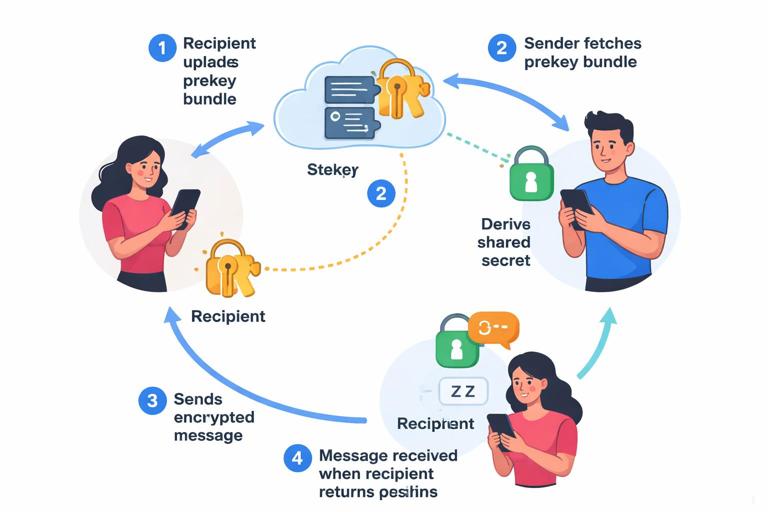

Pattern 4: Asynchronous Messaging with Prekeys

Idea: Recipients publish one-time or semi-static public “prekeys” to the server. Senders can start a session and send the first encrypted message even if the recipient is offline, by using a prekey to derive a shared secret.

Tradeoff: Enables offline delivery but introduces server-mediated key distribution and edge cases around prekey exhaustion, replay, and device provisioning.

Key Agreement and Session Lifecycle (Without Rehashing Crypto Basics)

Session lifecycle components: An E2EE session typically has (1) an initial handshake to establish shared secrets, (2) a message encryption phase where keys evolve, and (3) rekeying or session reset logic when devices change, keys rotate, or state is lost.

Why lifecycle matters: Most real failures in E2EE systems come from lifecycle bugs: stale sessions, mismatched state after reinstall, multi-device drift, or “helpful” server-side behavior that breaks assumptions (like reordering, duplication, or partial delivery).

Step-by-step: Starting a New 1:1 Session (Asynchronous)

Goal: Alice can send Bob an encrypted message even if Bob is offline, and both clients end up with a consistent session state.

- Step 1 — Bob publishes device key material: Bob’s device uploads a bundle containing an identity key (long-lived), a signed prekey (medium-lived), and a set of one-time prekeys (single-use). The server stores these bundles per device.

- Step 2 — Alice fetches Bob’s bundle: Alice requests Bob’s bundle for a specific device (or all devices) and verifies signatures on the signed prekey using Bob’s identity key.

- Step 3 — Alice creates an initial secret: Alice combines her ephemeral key with Bob’s prekeys to derive a shared secret and derives initial chain keys for sending and receiving.

- Step 4 — Alice sends a “prekey message”: Alice sends ciphertext plus the necessary public parameters (like her ephemeral public key and which one-time prekey was used) so Bob can derive the same secret.

- Step 5 — Bob consumes the one-time prekey: When Bob receives the message, he derives the same secret, marks that one-time prekey as used, and establishes the session state.

- Step 6 — Both sides transition to normal messaging: Subsequent messages use the established session and evolve keys per message.

Implementation note: You must handle duplicates and replays: Bob may receive the same prekey message twice (server retries), or out of order. Your session store needs idempotent processing keyed by message identifiers and handshake parameters.

Multi-Device E2EE: Patterns and Pitfalls

Device Graph Model

Reality: Users have multiple devices. E2EE must decide whether each device is an independent “end” (common) or whether devices share a single logical key (rare and risky).

Typical approach: Treat each device as a separate recipient with its own sessions. A message to “Bob” is actually encrypted to Bob’s phone, laptop, and tablet. This increases overhead and introduces consistency challenges.

Pattern: Per-Device Sessions + Fanout

How it works: The sender encrypts the message key separately for each recipient device (or uses sender keys in groups). The server fans out the ciphertext plus per-device encrypted key material.

Tradeoff: Strong isolation between devices (compromise of one device doesn’t automatically compromise others), but higher bandwidth and more complex delivery logic.

Pattern: Device Linking via Secure Transfer

Goal: Add a new device without giving the server plaintext or long-term secrets.

- Step 1 — Existing device generates a link secret: The existing device creates a short-lived linking secret and displays it as a QR code or numeric code.

- Step 2 — New device scans/enters the code: The new device uses the code to establish an encrypted channel directly with the existing device (often via the server as a relay but still E2EE).

- Step 3 — Existing device transfers key material: The existing device sends the minimum required state: identity keys, session state (optional), and group sender keys (if used). Prefer transferring only what is needed to decrypt future messages, not necessarily the entire history.

- Step 4 — Server registers the new device: The server adds the new device to the user’s device list and begins delivering messages to it.

Pitfall: If you transfer too much (like all session keys), you increase the blast radius if the new device is compromised. If you transfer too little, the new device can’t decrypt queued messages or join groups smoothly.

Tradeoff: History Sync vs. Forward-Only Devices

History sync: New devices can decrypt past messages. This is convenient but increases risk: compromise of a newly added device can reveal old content.

Forward-only: New devices only decrypt messages from the moment they join. This reduces risk but frustrates users and complicates “search across devices.” Many systems choose a hybrid: limited history window or user-controlled “restore from backup” with explicit consent.

Group E2EE: Membership Changes and Key Updates

Two Common Group Models

Model A — Pairwise fanout: Encrypt each message separately for each member device. Simple conceptually but expensive for large groups and attachments.

Model B — Sender keys: Each sender has a sender key per group; they distribute it to members using pairwise sessions. Messages are then encrypted once per sender. Efficient but requires careful handling of membership changes.

Step-by-step: Handling “Add Member” with Sender Keys

Goal: When Carol is added to a group, she should be able to read new messages but not necessarily old ones, depending on your policy.

- Step 1 — Update group roster: The server updates the group membership list and notifies clients. Clients treat roster updates as security-sensitive events.

- Step 2 — Rotate sender keys (recommended): Each existing sender rotates their sender key for the group to prevent the new member from decrypting older messages encrypted under the previous key.

- Step 3 — Distribute new sender keys to Carol: Each sender sends Carol their new sender key encrypted via their pairwise session with Carol’s device(s).

- Step 4 — Gate message sending on key distribution state: Clients may temporarily fall back to pairwise fanout or delay sending until key distribution completes, to avoid Carol missing messages.

Tradeoff: Rotating keys on membership change improves confidentiality boundaries but increases churn and can cause “can’t decrypt” errors if some devices are offline for long periods.

Step-by-step: Handling “Remove Member”

- Step 1 — Treat removal as urgent: Once Dave is removed, you must assume he may still have old sender keys and cached ciphertext.

- Step 2 — Rotate group secrets: Rotate sender keys (and any shared group state) so removed members cannot decrypt future messages.

- Step 3 — Enforce server-side delivery rules: The server must stop delivering new ciphertext to removed members’ devices. This is not sufficient alone (they might still get messages from other channels), but it reduces exposure.

- Step 4 — Client-side checks: Clients should verify the current roster before accepting or displaying group messages, to mitigate server bugs or malicious delivery.

Attachments and Large Media: Efficient E2EE Patterns

Pattern: Encrypt-Then-Upload with Content Addressing

Flow: The client encrypts the file locally, uploads ciphertext to object storage, then sends a small E2EE message containing the download URL (or object ID) plus the decryption key and integrity metadata.

Tradeoff: Efficient and scalable, but the URL/object ID becomes metadata. If you use content addressing (hash-based IDs), be careful: identical plaintext files produce different ciphertext if encryption is randomized, which is good for privacy; but you still must avoid leaking predictable identifiers.

Step-by-step: Attachment Send

- Step 1 — Generate an attachment key: Create a fresh key for the file (and optionally a separate key per chunk for streaming).

- Step 2 — Encrypt locally: Encrypt the file and compute integrity metadata needed for verification on download.

- Step 3 — Upload ciphertext: Upload encrypted bytes to storage. The server only sees ciphertext and size/timing metadata.

- Step 4 — Send an attachment pointer message: Send an E2EE message containing the object reference plus the attachment key and verification data.

- Step 5 — Recipient downloads and verifies: Recipient downloads ciphertext, verifies integrity, then decrypts locally.

Pitfall: If you allow the server to transform media (thumbnails, transcoding), you break E2EE unless transformations happen on the client. A common pattern is “client-side thumbnails” where the sender includes a small encrypted preview.

Identity Verification and Trust UX (The Hard Part Users Actually See)

Safety Numbers / Key Fingerprints

Concept: Users can verify each other’s identity keys out-of-band (scan QR, compare codes). This reduces the risk of a malicious server swapping keys, but it’s only effective if users actually do it and the UI makes changes obvious.

Tradeoff: Strong security for high-risk users, but adds friction. Many apps implement “trust on first use” (TOFU) with warnings on key changes; the warning design determines whether users ignore it.

Key Change Handling Patterns

Pattern A — Soft warning: Continue delivering messages but show “security code changed.” Usable, but users may miss it.

Pattern B — Hard stop: Block sending until the user re-verifies. Secure, but can break normal usage (device reinstall, lost phone) and increases support burden.

Pattern C — Contextual policy: Hard stop only for “verified contacts” or for high-sensitivity conversations; soft warning otherwise.

Backups, Recovery, and the “I Lost My Phone” Problem

Design Options

Option 1 — No cloud backup of keys: Maximum confidentiality, but users lose message history when they lose devices. Operationally simple but often unacceptable for mainstream products.

Option 2 — Encrypted backups with user-held key: Clients encrypt backups locally with a key derived from user input or stored in a secure enclave. The server stores only ciphertext. This improves recoverability but introduces UX around key entry and the risk of weak user-chosen secrets.

Option 3 — Multi-device escrow (device-to-device): Existing devices can restore a new device by transferring keys directly. Great when users still have one device, fails when they lose all devices.

Step-by-step: Encrypted Cloud Backup (Client-Controlled)

- Step 1 — Define what is backed up: Decide whether to back up identity keys, session state, group state, and message history. Minimizing backed-up secrets reduces blast radius.

- Step 2 — Encrypt backup locally: Produce a backup blob encrypted on the client. Include versioning and integrity checks so clients can reject malformed backups.

- Step 3 — Upload and rotate: Upload the encrypted blob and rotate periodically. Keep a small number of versions to recover from corruption.

- Step 4 — Restore with explicit user action: On a new device, require an explicit restore step and a recovery factor (passphrase, recovery key, or device transfer).

Pitfall: If your recovery factor is guessable or phishable, the backup becomes the weakest link. If it’s too strong and users lose it, recovery fails. This is a product decision as much as a cryptographic one.

Metadata, Traffic Analysis, and What E2EE Leaves Exposed

What servers still learn

Common metadata: sender and recipient identifiers, device identifiers, timestamps, message sizes, group membership, IP addresses, and delivery receipts. Even with perfect E2EE, this can reveal social graphs and behavior patterns.

Mitigation patterns (practical, not magical)

Padding and batching: Clients can pad messages to reduce size leakage and batch sends to reduce timing signals. This costs bandwidth and can increase latency.

Private contact discovery: If your app uploads address books, that’s a major metadata leak. Prefer privacy-preserving discovery mechanisms, but be realistic about complexity and server trust assumptions.

Sealed sender / sender anonymity: Some designs hide the sender identity from the server for certain message types by encrypting routing metadata for the recipient. This can reduce server visibility but complicates abuse handling and rate limiting.

Abuse Resistance vs. Privacy: Product-Security Tradeoffs

Reporting and moderation

Challenge: If the server can’t read content, it can’t trivially moderate it. You must decide how users report abuse and what evidence is available.

Pattern: User-submitted reports: The client can package reported messages (plaintext and context) and send them to the server when the user chooses to report. This preserves E2EE by default but allows targeted disclosure.

Tradeoff: Users can fabricate reports unless you include cryptographic provenance (e.g., signed message metadata). Provenance helps but can create privacy risks if over-collected.

Spam and rate limiting

Reality: E2EE does not stop spam. You still need rate limits, reputation, and friction. But you must implement them without inspecting content, relying on metadata and client signals.

Failure Modes and Defensive Engineering Patterns

Out-of-order, duplication, and partial delivery

Pattern: Design message processing to be idempotent and tolerant of reordering. Store per-session counters or message keys in a way that allows decrypting a limited window of out-of-order messages without permanently desynchronizing.

State loss and session resets

Pattern: Provide a safe “reset session” mechanism that re-establishes keys without silently downgrading security. Resets should be visible to users (at least in logs) and should not allow an attacker to force frequent resets to degrade privacy.

Cross-device consistency

Pattern: Treat device list changes as security events. When a new device is added, decide whether to (a) automatically start encrypting to it, (b) require approval on existing devices, or (c) require contact re-verification. Each choice affects usability and compromise containment.

Reference Architecture: Putting the Pieces Together

Client responsibilities

- Key state: Maintain identity keys, prekeys, session state, group state, and backup state.

- Encryption pipeline: Encrypt messages and attachments locally; attach the right headers for recipients to derive keys and verify integrity.

- Verification UX: Expose identity verification, key change warnings, and device list changes in a way users can act on.

- Recovery: Implement device linking and/or encrypted backups with explicit user consent.

Server responsibilities (still important in E2EE)

- Directory and device lists: Store user identifiers, device identifiers, and published prekey bundles.

- Message relay and queueing: Deliver ciphertext reliably with retries, ordering hints, and deduplication identifiers.

- Group roster management: Maintain membership lists and distribute roster updates.

- Abuse controls: Rate limiting, account controls, and report intake without requiring plaintext access.

Minimal message formats (conceptual)

// 1:1 message (conceptual fields, not a standard) message_id: random unique id sender_device_id: ... recipient_device_id: ... session_header: { ratchet_pub?: ..., prekey_ref?: ... } ciphertext: ...// attachment pointer message attachment: { object_id: ..., key: ..., integrity: ..., size: ... }Engineering note: Keep formats versioned. E2EE systems evolve; you will need to migrate clients without breaking decryption. Versioning also helps you deprecate weak behaviors (like legacy key change handling) safely.