Start With a Threat Model, Not With an Algorithm

A threat model is a structured description of what you are defending, who might attack it, what they can do, and what “winning” looks like for both sides. In practice, it prevents two common failures: over-engineering (wasting complexity where it doesn’t matter) and under-engineering (missing the one capability that breaks everything). For developers, the goal is not to predict every possible attack, but to make explicit assumptions so you can choose parameters, storage formats, and operational controls that match reality.

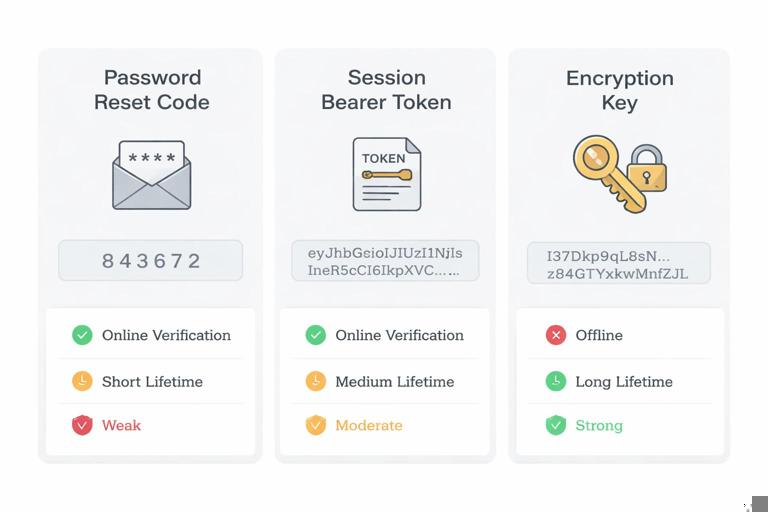

Threat modeling is also how you decide where entropy is required, how much is required, and what happens if it is partially lost. If you do not write down attacker capabilities, you cannot reason about whether a 6-digit code is “fine” (online rate-limited) or catastrophic (offline brute force). The same secret can be strong or weak depending on whether the attacker can test guesses locally, at high speed, without being detected.

Define the System: Assets, Trust Boundaries, and Data Flows

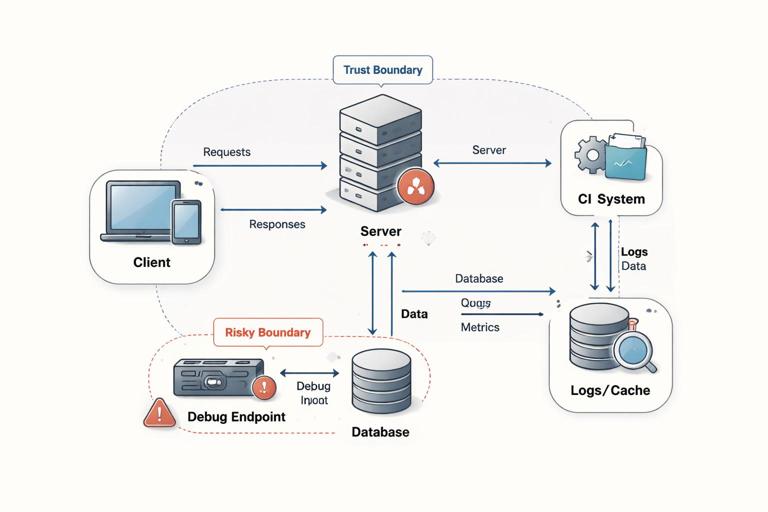

Before listing attackers, define what exists in your system and where secrets live. Start with assets: things you must protect. Common cryptography-relevant assets include long-term private keys, session keys, API tokens, password verifiers, recovery codes, encrypted backups, and integrity of software updates. Next, identify trust boundaries: places where data crosses from a component you control to one you do not fully control, such as client-to-server, service-to-service, browser-to-third-party script, or app-to-OS keystore.

Then draw data flows: how secrets are created, stored, transmitted, rotated, and destroyed. This is where developers often discover that “we encrypt it” is not a complete statement. You need to know: where is the key generated, where is it stored, who can read it, and what logs or caches might accidentally capture it. A simple diagram often reveals that the real risk is not the cipher but the boundary: a debug endpoint, a shared database role, or a CI system that can read production secrets.

Practical step-by-step: a minimal threat model worksheet

- List assets: write 5–10 items (e.g., “refresh tokens”, “database encryption key”, “admin session cookie signing key”).

- List entry points: APIs, login forms, file uploads, OAuth callbacks, mobile deep links, admin panels, background job queues.

- List trust boundaries: browser vs server, app vs OS, VPC vs internet, prod vs CI, tenant A vs tenant B.

- List data stores: databases, object storage, caches, logs, analytics pipelines, backups.

- For each asset, note: where it is created, where it is stored, where it is used, and who can access it.

Attacker Capabilities: The Questions That Change Everything

“Attacker capabilities” means what the attacker can actually do, not what you hope they cannot do. Capabilities determine whether attacks are online or offline, whether they can observe secrets, whether they can modify messages, and whether they can scale. When you choose cryptographic parameters, you are implicitly choosing a security margin against a set of capabilities.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Key capability dimensions that matter for developers include: read access (can they read a database dump?), write access (can they modify records or inject messages?), network position (can they observe or tamper with traffic?), execution (can they run code on a client device or server?), and time/scale (can they try billions of guesses?). A threat model should state these explicitly, because a design that is safe against an online attacker can fail instantly against an offline attacker.

Online vs offline guessing

Online guessing means the attacker must send each guess to your system and you can rate-limit, lock accounts, require CAPTCHA, or alert. Offline guessing means the attacker has enough data to verify guesses locally (for example, a leaked password verifier, an encrypted file with a guess-checkable structure, or a token signed with a weak secret). Offline guessing is usually the worst case for entropy requirements because the attacker can parallelize and run at hardware speed.

Read-only vs read-write compromise

A read-only database leak is already serious, but read-write changes the game: attackers can swap public keys, change account recovery settings, replace encrypted blobs, or alter authorization rules. If your design assumes stored data is trustworthy, a write-capable attacker can often escalate. This is why integrity protection (authenticity) matters for stored configuration and key material, not just confidentiality.

Local device compromise

If the attacker can run code on the client device (malware, rooted phone, malicious browser extension), many cryptographic guarantees collapse. They can read plaintext before encryption, capture passwords as typed, or exfiltrate keys from memory. Threat models often separate “remote attacker” from “local attacker” and decide what is in scope. For example, you might aim to protect data at rest against a stolen laptop (disk encryption) but not against an active malware infection.

Entropy: What It Is and Why Developers Misjudge It

Entropy is a measure of unpredictability. In security engineering, you can treat it as “how many guesses an attacker must try” in the best possible attack. If a secret has N bits of entropy, a brute-force attacker needs about 2^(N-1) guesses on average to find it. The key point is that entropy is about the attacker’s uncertainty, not about the length of the string or how “random-looking” it appears.

Developers misjudge entropy when they confuse encoding with randomness. A 32-character hex string looks complex, but if it is derived from a timestamp and a counter, its entropy may be tiny. Conversely, a short string can be strong if it is truly random and long enough in bits. Another common mistake is assuming that “users will choose something unpredictable.” Human-chosen secrets usually have far less entropy than their length suggests.

Bits of entropy in practice

To estimate entropy, start with the size of the search space the attacker must cover. If a token is uniformly random over 128 bits, the search space is 2^128. If a 6-digit code is uniformly random, the search space is 10^6, which is about 2^20 (because 2^10 ≈ 1024 ≈ 10^3). That means a 6-digit code has roughly 20 bits of entropy. Whether 20 bits is acceptable depends entirely on attacker capabilities: online with strict rate limits might be fine; offline is not.

Entropy vs security level

Security level is the work required for the best known attack. For brute force, it aligns with entropy. But the effective security level can be lower if the attacker has side information (partial leaks, predictable structure, biased RNG) or if the system allows faster-than-expected verification (offline checks, no throttling, parallelization). Your threat model should therefore include not just “how many bits,” but also “how many guesses per second can the attacker realistically achieve” and “can they verify guesses offline.”

Where Entropy Comes From: RNGs, Environments, and Failure Modes

In real systems, entropy typically comes from a cryptographically secure random number generator (CSPRNG) provided by the operating system. The OS collects environmental noise and maintains an internal state that produces unpredictable bytes. Your job as a developer is to use the right API, use it correctly, and avoid patterns that reduce entropy (like truncating too much, reusing nonces, or deriving secrets from predictable inputs).

Entropy failures often happen at boundaries: early boot on embedded devices, container images cloned with the same seed, virtual machines restored from snapshots, or application code that falls back to insecure randomness when the secure API fails. Another failure mode is “randomness laundering,” where a strong random value is transformed into a weaker one by mapping it into a small space (e.g., taking random bytes and using modulo to get a short code without considering bias, or truncating to too few characters).

Practical step-by-step: generating secrets safely

- Use OS CSPRNG APIs: in most languages, prefer the standard “secure random” library that is explicitly documented as cryptographically secure.

- Generate enough bits: decide the required entropy from the threat model (e.g., 128 bits for bearer tokens, more if long-lived and high-value).

- Encode without shrinking: base64 or hex encoding changes representation, not entropy, as long as you keep all bytes.

- Avoid predictable derivations: do not derive secrets from timestamps, user IDs, or incremental counters.

- Handle failures explicitly: if secure randomness is unavailable, fail closed rather than silently using a weaker PRNG.

Mapping Threat Models to Entropy Requirements

Entropy requirements should be derived from how the secret is used and what the attacker can do. A useful approach is to classify secrets by (1) whether they are guessable offline, (2) how long they remain valid, and (3) what damage occurs if they are guessed. A short-lived code used in an online flow can be much shorter than a long-lived bearer token that grants API access.

For example, consider three secrets: a password reset code, a session identifier, and an encryption key. A reset code is typically verified online and can be rate-limited; it can be shorter but must expire quickly and be bound to a specific account and context. A session identifier is often a bearer token: anyone who has it can act as the user, so it needs high entropy because it might be exposed via logs, referrers, or browser storage. An encryption key must resist offline brute force entirely; it should be generated randomly with sufficient bits and never be user-chosen.

Practical step-by-step: choosing an entropy target

- Decide online vs offline: can an attacker verify guesses without talking to you? If yes, treat it as offline and require high entropy.

- Estimate attacker rate: for offline, assume high parallelism; for online, assume your rate limits and monitoring work as designed.

- Set a work factor goal: choose a target like “impractical within the token lifetime” or “impractical for years.”

- Translate to bits: pick a bit-length that makes brute force infeasible under that capability set.

- Add operational controls: expiration, rotation, binding to context, and detection reduce reliance on entropy alone.

Attacker Models You Can Reuse

Reusable attacker models help teams communicate. Instead of “a hacker,” define a few tiers and map features to them. For example: a remote opportunist (no special access, uses common tools), a targeted attacker (patient, can phish, can buy data dumps), an insider (legitimate access to some systems), and a platform-level attacker (controls a client device or has cloud account access). Each tier implies different entropy and integrity requirements.

When you document a threat model, write what is explicitly out of scope too. If you are not defending against a compromised client device, say so, and then ensure your design does not accidentally claim it does. This prevents security theater and helps reviewers focus on realistic controls, like protecting tokens in transit and at rest, rather than promising to defeat malware with encryption alone.

Concrete Scenarios: How Capabilities Change the Design

Scenario 1: Password reset codes

If reset codes are verified online, you can rely on throttling and expiration. But if you store a reset token in a way that allows offline verification (for example, a token that is a MAC of the email with a weak secret, or a predictable token), an attacker who obtains the database or secret can brute force it. A robust design assumes the attacker may obtain the database and still should not be able to generate valid reset tokens without a high-entropy server secret and proper binding.

Operationally, the attacker capability that matters most is whether they can attempt many guesses without detection. Rate limits should be per account, per IP, and per device fingerprint where possible, and the code should expire quickly. Entropy can be moderate only if these controls are strong and the code is single-use.

Scenario 2: API keys and bearer tokens

Bearer tokens are frequently exposed accidentally: logs, browser storage, crash reports, analytics, referer headers, or copy-paste. Threat models should assume partial leakage is plausible. Because an attacker only needs to guess or obtain one valid token, these tokens should be high entropy and unstructured (no predictable prefixes that reduce search space). If tokens are long-lived, rotation and scoping become as important as entropy.

Scenario 3: Encrypted backups

Backups are a classic offline target: an attacker who steals an encrypted backup can attempt guesses indefinitely. This means the encryption key must not be derived from low-entropy material. If humans must unlock backups, the threat model must include offline guessing and you must use a design that makes each guess expensive and enforces strong passphrases. If the key is machine-generated and stored in a key management system, the threat model shifts to attacker capabilities around cloud IAM, service accounts, and audit logs.

Documenting Assumptions and Security Invariants

A threat model is most useful when it produces concrete invariants: statements that must remain true for the system to be secure. Examples: “An attacker who reads the user database cannot impersonate users without also obtaining the token signing key,” or “Reset codes are single-use, expire in 10 minutes, and are rate-limited to 5 attempts per hour per account.” These invariants are testable and can be enforced with code and monitoring.

Write assumptions in the same way. Examples: “The OS CSPRNG is available and correctly seeded,” “TLS is terminated only at our load balancer,” “Production secrets are not accessible from CI,” “Client devices may be compromised and are out of scope.” When an incident happens, these assumptions guide investigation: you can quickly see which assumption failed and which controls need strengthening.

Practical step-by-step: turning a threat model into engineering tasks

- Create a table with columns: Asset, Threat, Attacker capability, Impact, Control, Test/Monitor.

- For each asset, list at least one offline and one online threat (even if you later mark one as out of scope).

- Attach entropy requirements to each secret: bit length, lifetime, storage location, rotation policy.

- Add abuse cases: “attacker has DB dump,” “attacker can replay requests,” “attacker can write to cache,” “attacker can read logs.”

- Define tests: unit tests for token length/format, integration tests for rate limits, alerts for anomalous verification failures.

Common Pitfalls: Where Teams Get Threat Models and Entropy Wrong

A frequent pitfall is treating all secrets the same. Teams might use short random strings everywhere because “it’s random,” without considering offline attacks. Another pitfall is ignoring where verification happens. If a secret is checked locally (offline), entropy must be high; if checked online, you can trade entropy for rate limits and expiration, but only if those controls are reliable and monitored.

Another pitfall is forgetting that attackers chain capabilities. A “read-only” log leak might reveal tokens; a “minor” SSRF might reach metadata services; a “small” misconfiguration might expose a signing key. Threat models should consider realistic escalation paths: what a remote attacker can become after one foothold. This is also why you should avoid single points of failure: a single low-entropy secret used as a master key, or a single shared token across environments.

Finally, teams often fail to update threat models. Changes like adding a mobile client, introducing a third-party analytics script, or moving to a new cloud provider can change attacker capabilities. Treat the threat model as a living artifact tied to architecture changes, not a one-time document.