What “safe symmetric encryption” means in practice

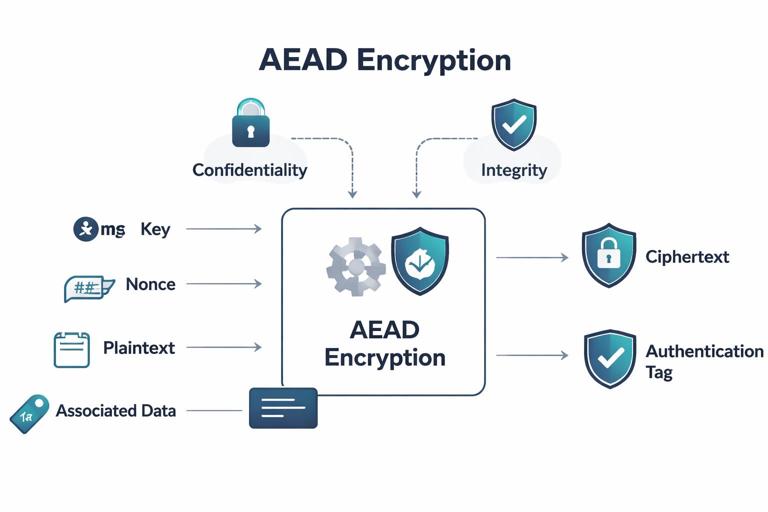

Safe symmetric encryption is not just “pick AES and you’re done.” In real applications, safety comes from using a modern authenticated-encryption scheme, generating and managing nonces correctly, binding ciphertext to its context (so it can’t be replayed or transplanted), and handling keys and failures in a way that doesn’t quietly disable security. The goal is to provide confidentiality (attackers can’t read the plaintext) and integrity/authenticity (attackers can’t modify ciphertext to produce a meaningful plaintext) under realistic operational conditions: multiple messages, multiple devices, crashes, retries, and partial compromise.

In practice, “safe” usually means using an AEAD (Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data) construction such as AES-GCM, AES-GCM-SIV, ChaCha20-Poly1305, or XChaCha20-Poly1305, and using it through a well-reviewed library API that enforces correct parameter sizes. It also means you treat encryption as a protocol: you define what goes into associated data, how nonces are created, how keys rotate, how you store metadata, and how decryption errors are handled.

Choose an AEAD mode (and know why)

AEAD gives you encryption plus a MAC in one operation, with a single key (or internally derived subkeys) and a single “decrypt-and-verify” step. This prevents classic pitfalls like “encrypt-then-MAC but verify wrong,” “MAC-then-encrypt with padding oracles,” or “encryption without integrity.” If your application currently uses AES-CBC with PKCS#7 and a separate HMAC, you can make it safe, but it’s easier to get wrong than using AEAD directly.

Common AEAD choices: AES-GCM is fast on CPUs with AES-NI and widely available. ChaCha20-Poly1305 is fast and constant-time on a broad range of devices, especially mobile and embedded. XChaCha20-Poly1305 extends ChaCha20-Poly1305 with a larger nonce, making nonce management easier. AES-GCM-SIV is a misuse-resistant variant that tolerates accidental nonce reuse better than AES-GCM (it still has limits, but it avoids catastrophic failures from a repeated nonce).

- Default recommendation for general apps: ChaCha20-Poly1305 or AES-GCM (depending on platform support).

- If you cannot guarantee unique nonces: prefer AES-GCM-SIV or XChaCha20-Poly1305 (larger nonce reduces collision risk; SIV reduces damage from repeats).

- Avoid “roll your own” modes and avoid raw AES-ECB entirely.

Nonces: uniqueness is a requirement, not a suggestion

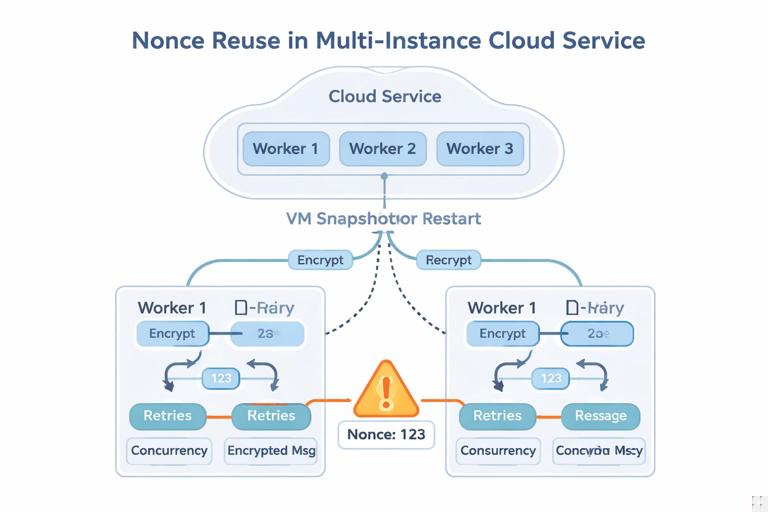

Most AEADs require a nonce (sometimes called IV). For AES-GCM and ChaCha20-Poly1305, the nonce must be unique per key. Reusing a nonce with the same key can leak relationships between plaintexts and can allow forgeries. This is one of the most common real-world failure modes because it shows up under concurrency, retries, VM snapshots, restored backups, or multiple processes sharing a key without coordination.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

There are three practical strategies for nonce generation. First, use a counter-based nonce: store a per-key counter and increment it for every encryption. This is robust but requires reliable state persistence and atomic increments. Second, use a random nonce: generate a fresh random nonce each time; this is simple but relies on a large nonce space to make collisions negligible, and it still fails if your RNG is broken or if you encrypt enormous volumes. Third, use a structured nonce: combine a random per-process prefix with a counter suffix, which avoids coordination across processes while keeping uniqueness.

Step-by-step: structured nonce for multi-process services

This pattern works well for services that may run multiple instances and need to encrypt many records with the same key.

- At process start, generate a random 64-bit prefix (store in memory).

- Maintain a 32-bit counter starting at 0 (in memory). If the process restarts, the prefix changes, so counters can restart safely.

- Nonce = prefix || counter (total 96 bits, suitable for AES-GCM).

- On each encryption, increment the counter. If the counter overflows, rotate the key and restart the process or regenerate a new prefix and reset counter with a new key.

For XChaCha20-Poly1305 you have a 192-bit nonce, so you can use a random nonce each time with extremely low collision probability, but you still must ensure you never intentionally reuse a nonce with the same key.

Associated Data (AAD): bind ciphertext to its context

AEAD lets you authenticate additional data that is not encrypted. This is essential for real applications because ciphertext often travels with metadata: record IDs, user IDs, protocol versions, message types, timestamps, or routing information. If you don’t bind that metadata, an attacker might be able to take a ciphertext from one context and replay it in another, or swap fields around while keeping the ciphertext intact.

Use AAD to authenticate the “meaning” of the ciphertext. For example, if you encrypt a user’s email address for storage, you can include the user ID and the database column name as AAD. Then even if an attacker copies the ciphertext into another user’s row, decryption will fail because the AAD won’t match.

Step-by-step: define AAD for an encrypted database field

- Decide what must be bound: table name, column name, primary key, tenant ID, and a schema version.

- Serialize AAD deterministically (e.g., UTF-8 strings with separators, or a compact binary format).

- On encryption, pass AAD to AEAD along with nonce and plaintext.

- On decryption, reconstruct the exact same AAD from the current row context and verify.

AAD must be byte-for-byte identical on encrypt and decrypt. If you include JSON, ensure stable key ordering and encoding; otherwise you’ll get intermittent failures. A simple canonical binary encoding is often safer than “stringly typed” AAD.

Key management in application terms (without hand-waving)

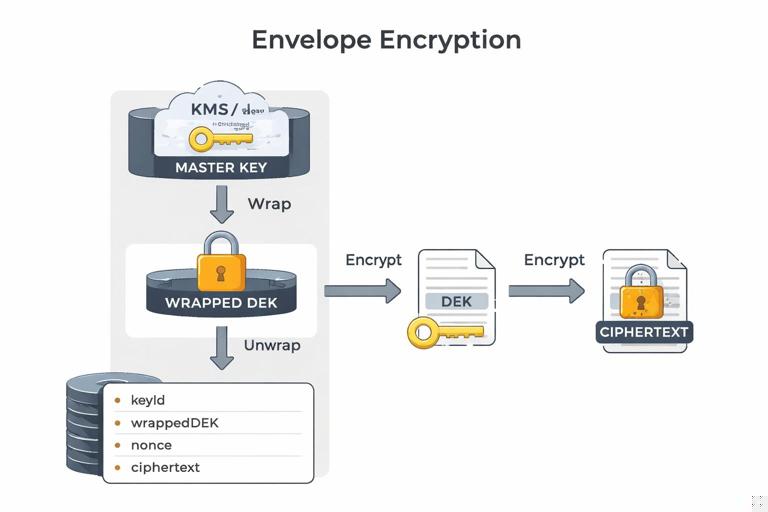

Symmetric encryption is only as safe as the key lifecycle around it. In application code, that means: where keys come from, how they’re stored, how they’re rotated, and how you limit blast radius. A practical approach is to use envelope encryption: a long-lived master key (kept in an HSM/KMS or OS key store) encrypts short-lived data encryption keys (DEKs). Your application uses DEKs to encrypt data, and stores the encrypted DEK alongside the ciphertext.

Envelope encryption reduces exposure: you can rotate the master key without re-encrypting all data, and you can rotate DEKs per object, per user, or per time window. It also makes it easier to separate duties: the database stores encrypted blobs, while the KMS controls access to unwrap DEKs.

Step-by-step: envelope encryption for stored records

- Generate a random DEK (e.g., 256-bit) for a record or a batch of records.

- Ask KMS/HSM to wrap (encrypt) the DEK under a master key, returning wrappedDEK and a key identifier.

- Encrypt the plaintext with AEAD using the DEK, a nonce, and AAD that includes the key identifier and record context.

- Store: keyId, wrappedDEK, nonce, ciphertext, tag (often tag is part of ciphertext in APIs), and any non-secret metadata needed to rebuild AAD.

- On read: unwrap DEK via KMS using wrappedDEK and keyId, then AEAD-decrypt with the same nonce and AAD.

Even if you don’t have a KMS, you can still apply the pattern with an OS-protected master key (e.g., Windows DPAPI, macOS Keychain, Linux kernel keyring) and keep wrapped DEKs in the database.

Message format: make it explicit and versioned

Many encryption failures come from ambiguous or ad-hoc serialization. Define a clear binary or structured format for encrypted payloads, including algorithm identifiers and version numbers. This prevents “silent downgrade” bugs and makes future migrations possible. A typical format includes: version, algorithm, key ID, nonce, ciphertext, and tag. Some libraries combine ciphertext and tag; still store fields explicitly so you can parse safely.

Keep the format unambiguous: fixed-length fields for nonce and tag when possible, length-prefix variable fields, and reject unknown versions. If you use base64 for transport, base64-encode the whole binary blob rather than encoding each field separately, unless you have a strong reason.

// Example logical layout (not a standard; define your own carefully):

// [1 byte version][1 byte alg][4 bytes keyId]

// [1 byte nonceLen][nonce][4 bytes ctLen][ciphertext+tag]

Decryption: treat authentication failure as a hard failure

AEAD decryption either returns the plaintext (verified) or fails authentication. Your application must treat authentication failure as “data is corrupted or malicious” and stop. Do not return partial plaintext. Do not attempt to “fix” it. Do not fall back to another algorithm automatically. If you need migration, use explicit versioning and controlled re-encryption paths.

Also avoid leaking information through error messages or timing. Many libraries already implement constant-time tag checks, but you can still leak by returning different HTTP status codes or different error strings for “bad tag” vs “bad format.” A practical approach is to log detailed errors internally (rate-limited) and return a generic error to callers.

Step-by-step: safe decrypt handler in a web service

- Parse and validate the message format (length checks, version checks) before calling decrypt.

- Reconstruct AAD from request context (tenant ID, record ID, version).

- Call AEAD decrypt; if it fails, return a generic “invalid data” response and do not reveal which check failed.

- Log an internal event with correlation ID, but avoid logging plaintext, keys, nonces, or full ciphertext.

Randomness: what you actually need at runtime

For symmetric encryption, you typically need randomness for keys and sometimes for nonces. Use the operating system’s cryptographically secure random generator (CSPRNG) via your language’s standard library (for example, getrandom/urandom on Linux, BCryptGenRandom on Windows, SecRandomCopyBytes on Apple platforms). Avoid custom PRNGs, timestamps, or “unique IDs” as nonce sources unless they are part of a structured uniqueness scheme.

In containerized and serverless environments, ensure the runtime has access to the OS CSPRNG early in boot. Most modern systems do, but if you run in unusual minimal environments, verify that your language runtime is not falling back to insecure randomness.

Practical recipes

Recipe: encrypting API tokens for storage (server-side)

Suppose you store third-party API tokens in your database and need to decrypt them to call the provider. Requirements: confidentiality at rest, integrity, and binding to the owning user/tenant so tokens can’t be swapped.

- Use envelope encryption: per-token DEK wrapped by KMS.

- Use AEAD (AES-GCM or ChaCha20-Poly1305).

- AAD includes tenantId, userId, tokenId, and a purpose string like “api_token_v1”.

- Nonce generated per encryption (structured nonce or random nonce with large space).

// Pseudocode

DEK = random(32)

wrappedDEK = KMS.wrap(masterKeyId, DEK)

nonce = makeNonce()

aad = encode("api_token_v1", tenantId, userId, tokenId)

ciphertext = AEAD.encrypt(DEK, nonce, plaintextToken, aad)

store {masterKeyId, wrappedDEK, nonce, ciphertext}

On read, unwrap DEK and decrypt with the same AAD. If the row is copied to a different user, AAD mismatch causes decryption failure.

Recipe: encrypting local files in a desktop/mobile app

Local encryption often fails because keys are stored next to the ciphertext. Use the platform key store to protect a master key, and derive or generate a file key per file. Store file metadata (nonce, version) alongside the ciphertext in the file header.

- Master key stored in OS key store (non-exportable if possible).

- Per-file DEK generated randomly and wrapped by master key.

- AEAD with AAD including app identifier, file type, and file format version.

- Nonce stored in file header; ciphertext follows.

// File header idea:

// MAGIC(4) | VER(1) | ALG(1) | wrappedDEKLen(2) | wrappedDEK | nonceLen(1) | nonce | ciphertext

This design supports future algorithm upgrades by bumping VER and ALG and re-encrypting files when opened.

Recipe: encrypting messages between services

For service-to-service encryption, you often already have TLS. Symmetric encryption still appears in message queues, event logs, or when you need end-to-end protection across intermediaries. Here, nonce uniqueness and replay resistance matter.

- Use per-sender key (or per-connection session key) to reduce nonce coordination scope.

- Nonce strategy: senderId prefix + counter, or XChaCha20 random nonce.

- AAD includes message type, senderId, receiverId, protocol version, and a message ID.

- Include a message ID and enforce replay checks at the application layer (e.g., store recent IDs or use monotonic counters per sender).

Encryption alone does not stop replay; you need an application rule that rejects duplicates or out-of-window messages. AEAD ensures the message ID can’t be altered, but you must still check it.

Key rotation and algorithm agility without breaking everything

Real systems need rotation: periodic, on suspected compromise, or to migrate algorithms. Rotation is easiest when your ciphertext format includes a key identifier and version. For stored data, you can rotate lazily: decrypt with the old key on read, then re-encrypt with the new key and write back. For high-throughput systems, you can rotate by time windows: new writes use the new key; reads try the indicated key ID.

Algorithm agility means you can introduce a new AEAD without ambiguity. Do not “try decrypt with AES-GCM, if fails try ChaCha20-Poly1305” because authentication failure is indistinguishable from wrong key/nonce/AAD and can become an oracle. Instead, store an explicit algorithm ID and reject unknown IDs.

Step-by-step: lazy rotation for database records

- Store keyId and algId with each ciphertext.

- On read: select key by keyId, decrypt using algId.

- If keyId is not current: re-encrypt plaintext with current keyId/algId and update the row in the same transaction (or via a background job).

- After a grace period, disable old keys for decryption only when you are sure all records have been migrated.

Common implementation pitfalls (and how to avoid them)

Using the right primitive is not enough; many failures are integration bugs. One pitfall is nonce reuse due to “random nonce” plus insufficient nonce size or too many encryptions. Another is truncating tags to save space; many AEADs allow shorter tags, but it reduces integrity security and is rarely worth it. Another is encoding mistakes: mixing up base64 variants, losing leading zeros in nonces, or accidentally treating bytes as UTF-8 strings.

- Never reuse a nonce with the same key; design for uniqueness under concurrency and restarts.

- Keep full-length authentication tags unless you have a quantified reason and a reviewed design.

- Validate lengths before decrypting; reject malformed inputs early.

- Do not compress after encrypting (it does nothing) and be careful compressing before encrypting if attacker-controlled data is mixed with secrets.

- Do not log secrets: plaintext, keys, nonces, or full ciphertext blobs.

Testing and verification you can automate

You can catch many encryption integration bugs with deterministic tests and property-based checks. For example, verify that decrypt(encrypt(m)) returns m for a range of message sizes, including empty plaintext and very large plaintext. Verify that changing any bit of ciphertext or tag causes decryption to fail. Verify that changing AAD causes failure. Verify that nonces are never repeated in your nonce generator under simulated concurrency.

Step-by-step: build a nonce-reuse test

- Instrument your encryption function to expose the nonce it used (in test builds only).

- Run N parallel workers encrypting messages with the same key.

- Collect all nonces into a set and assert there are no duplicates.

- Repeat across process restarts if your scheme depends on persisted counters or prefixes.

Also test migration paths: can you decrypt old versions, and do you re-encrypt correctly? These tests prevent “we rotated keys and bricked old data” incidents.