Threat Model for GraphQL in Production

Security hardening starts by naming what you are defending against. In GraphQL, the most common production threats are not “GraphQL-specific hacks” but predictable abuse patterns amplified by GraphQL’s flexibility: schema reconnaissance, injection into downstream systems through resolver inputs, and resource exhaustion through high request volume or expensive operations. A practical threat model for this chapter focuses on three areas: (1) introspection and schema discovery controls, (2) injection vectors across resolvers and data sources, and (3) rate limiting and operational throttles that keep the API available under abuse.

GraphQL’s single endpoint can make perimeter defenses (like path-based WAF rules) less effective, so controls often move closer to the execution layer: validating the request, constraining what operations can run, and enforcing per-actor limits. The goal is not to make the API “unusable for attackers” in an absolute sense, but to reduce the blast radius: prevent easy discovery, prevent untrusted input from becoming executable in downstream systems, and prevent one client from consuming disproportionate resources.

Introspection Control: Reducing Schema Reconnaissance

What introspection enables and why it matters

Introspection is a GraphQL feature that allows clients to query the schema itself using fields like __schema and __type. It is essential for developer tooling, but it also gives attackers a map of your API: types, fields, arguments, and descriptions. With introspection enabled in production, an attacker can quickly enumerate sensitive operations (for example, mutations that change account state) and craft targeted queries without guessing.

Disabling introspection is not a complete security strategy—attackers can still infer parts of the schema from errors or observed traffic—but it removes a high-leverage discovery mechanism. Many teams choose a middle path: allow introspection only for trusted actors (internal networks, admin roles, or specific API keys) and block it for public clients.

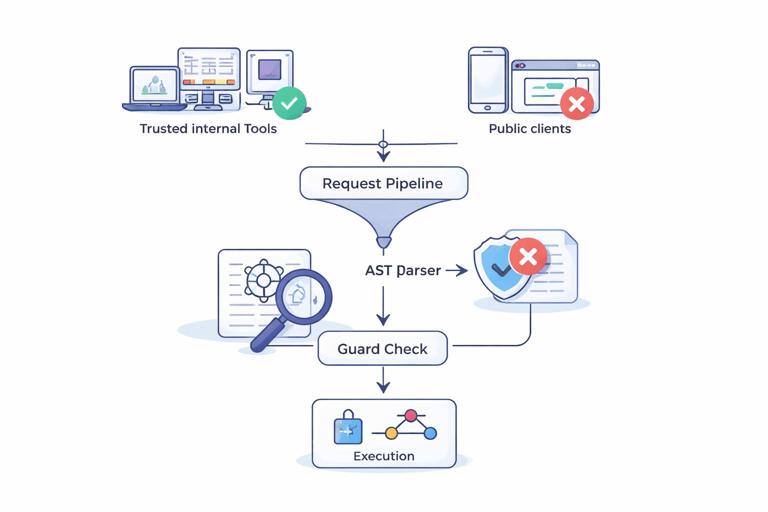

Step-by-step: Blocking introspection in the request pipeline

A robust approach is to block introspection at the document level before execution. Relying only on “environment flags” in GraphQL servers can be fragile if multiple endpoints or gateways exist. The steps below describe a portable strategy that works in most GraphQL server stacks.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

- Step 1: Parse the incoming query document. Ensure you parse the GraphQL document (query string) into an AST. Most servers already do this as part of execution; you can hook earlier in the pipeline if your framework supports it.

- Step 2: Detect introspection fields. Walk the AST and reject any operation that selects

__schemaor__type. Also consider blocking__typenameonly if you have a specific reason; it is widely used by clients and is less sensitive than full schema introspection. - Step 3: Apply conditional allow rules. If the request is from a trusted actor (for example, an internal admin token), allow introspection; otherwise reject with a generic error message.

- Step 4: Return a client-safe error. Use a consistent error response that does not reveal whether introspection exists. For example, respond with “Operation not permitted.” Avoid returning “Introspection is disabled,” which confirms the control and can help attackers tune their approach.

// Pseudocode: introspection guard (framework-agnostic) function isTrustedForIntrospection(ctx) { return ctx.actor?.isAdmin === true || ctx.apiKey?.scopes?.includes("schema:read"); } function containsIntrospection(ast) { // Walk selections; return true if any field name is __schema or __type return visit(ast, { Field(node) { if (node.name.value === "__schema" || node.name.value === "__type") return true; } }) === true; } function guardIntrospection({ query, ctx }) { const ast = parse(query); if (containsIntrospection(ast) && !isTrustedForIntrospection(ctx)) { throw new GraphQLError("Operation not permitted"); } return ast; }Persisted operations as an alternative to introspection for public clients

If your public clients need a stable way to build queries without introspection, use a workflow where the client ships only an operation identifier and the server looks up the stored document. This reduces the need for runtime schema discovery and also shrinks the attack surface for ad-hoc query text. In practice, teams often combine: (1) introspection allowed only for internal tooling, (2) persisted operations for public clients, and (3) strict rejection of unknown operations.

Hardening details: descriptions, deprecations, and metadata

Even if you allow introspection for trusted actors, treat schema metadata as sensitive. Field descriptions sometimes contain internal URLs, implementation hints, or references to systems. Keep descriptions helpful but avoid leaking infrastructure details. For deprecations, avoid embedding migration instructions that reveal internal endpoints or privileged behaviors. If you publish a public schema for SDK generation, consider generating a “public view” that omits internal-only fields and descriptions.

Injection Vectors: Preventing Untrusted Input from Becoming Executable

Where injection happens in GraphQL

GraphQL itself is not “SQL-injection-prone” by default; the injection risk appears when resolver inputs are interpolated into downstream queries, templates, or commands. GraphQL increases the number of input paths because arguments can be nested (inputs inside inputs), and because a single request can trigger multiple resolvers. Injection hardening is therefore about disciplined input handling at resolver boundaries and safe APIs for downstream systems.

Common injection targets in GraphQL backends include: SQL databases (SQL injection), document databases (NoSQL injection), search engines (query DSL injection), template engines (server-side template injection), command execution (shell injection), and URL fetchers (SSRF). The same GraphQL argument might flow into multiple systems (for example, a search term used in both SQL and Elasticsearch), so you need consistent validation and encoding rules.

Step-by-step: Build an input validation layer for resolvers

Relying only on GraphQL types is not enough. A GraphQL String does not constrain length, character set, or semantics. A practical pattern is to validate inputs at the edge of each operation (query/mutation) and normalize them before calling data sources.

- Step 1: Define validation rules per operation. For each operation, list the arguments and constraints: length limits, allowed characters, numeric ranges, and required formats (email, UUID, ISO date).

- Step 2: Normalize before use. Trim whitespace, normalize Unicode if relevant, and convert to canonical forms (for example, lowercase emails) to avoid bypasses.

- Step 3: Reject unexpected fields. For input objects, reject unknown keys rather than ignoring them. This prevents “hidden” parameters from reaching downstream query builders.

- Step 4: Centralize validation errors. Return consistent, client-safe validation errors without echoing raw input back to the client.

// Example: validation helper (pseudocode) function validateSearchArgs(args) { const q = (args.query ?? "").trim(); if (q.length === 0) throw new UserInputError("query is required"); if (q.length > 100) throw new UserInputError("query is too long"); // Allow letters, numbers, spaces, basic punctuation; tune for your domain if (!/^[\p{L}\p{N} .,'"-]+$/u.test(q)) { throw new UserInputError("query contains invalid characters"); } return { query: q }; }SQL injection: parameterize, never concatenate

In SQL-backed resolvers, the primary rule is to use parameterized queries or a query builder that guarantees parameterization. Avoid building SQL fragments from raw GraphQL arguments, especially for ORDER BY, column names, or dynamic filters. Attackers often target these “non-value” parts because developers sometimes parameterize values but still concatenate identifiers.

For dynamic sorting, map client-provided sort keys to a fixed allowlist of columns. For filtering, map allowed filter fields to known columns and operators. If you must support advanced search syntax, parse it into an AST and compile it to parameterized SQL, rather than passing it through.

// Example: safe ORDER BY mapping (pseudocode) const SORT_MAP = { CREATED_AT: "created_at", NAME: "name" }; function buildOrderBy(sort) { const col = SORT_MAP[sort?.field ?? "CREATED_AT"]; if (!col) throw new UserInputError("Invalid sort field"); const dir = sort?.direction === "DESC" ? "DESC" : "ASC"; return `${col} ${dir}`; // col is from allowlist, dir is constrained // Values still parameterized separately }NoSQL and query DSL injection: avoid passing raw objects

In document databases and search engines, injection often happens when developers pass user-controlled objects directly into a query API. For example, allowing a GraphQL input object to become a MongoDB filter can enable operators like $where or unexpected nested operators. Similarly, passing raw strings into a search DSL can enable expensive queries or bypass intended constraints.

Mitigations include: (1) build queries from primitives, not from user-provided objects; (2) maintain allowlists of operators; (3) enforce maximum complexity on search expressions; and (4) strip or reject keys that start with special operator prefixes (like $) unless explicitly allowed.

Template injection and unsafe string rendering

If resolvers generate emails, documents, or HTML using templates, treat user input as data, not template code. Use template engines that auto-escape by default, and never evaluate user-provided strings as templates. For example, do not store a “custom email template” from users and render it server-side unless you have a sandboxed, restricted templating system.

Also consider log injection: if you log raw arguments, attackers can inject newlines or structured log fields to confuse log parsers. Normalize and escape values before logging, and prefer structured logging where fields are separate rather than concatenated strings.

SSRF and outbound fetches from resolvers

Resolvers sometimes fetch URLs (for example, to validate a webhook endpoint, fetch an image, or call partner APIs). If any part of the URL is influenced by user input, you risk server-side request forgery (SSRF), where an attacker forces your server to call internal services or metadata endpoints.

- Allowlist domains or base URLs; do not accept arbitrary URLs.

- Resolve DNS and block private IP ranges; be careful with redirects that change the destination.

- Set tight timeouts and response size limits to prevent resource exhaustion.

- Do not forward sensitive headers to user-influenced destinations.

// Example: safe outbound call pattern (pseudocode) const ALLOWED_HOSTS = new Set(["api.partner.example", "cdn.partner.example"]); function assertAllowedUrl(raw) { const u = new URL(raw); if (u.protocol !== "https:") throw new UserInputError("Invalid URL"); if (!ALLOWED_HOSTS.has(u.hostname)) throw new UserInputError("Host not allowed"); return u; } async function fetchPartner(rawUrl) { const u = assertAllowedUrl(rawUrl); return httpFetch(u.toString(), { timeoutMs: 2000, maxBytes: 1_000_000 }); }GraphQL document injection vs. variable safety

Another subtle vector is when servers build GraphQL queries to call downstream GraphQL services (schema stitching, federation-like patterns, or internal GraphQL-to-GraphQL calls). If you interpolate user input into a GraphQL document string, you can create a GraphQL injection vulnerability. The safe pattern is to keep the document static and pass user input only through variables. Also, avoid allowing clients to provide fragments or raw selection sets that get appended server-side.

Rate Limiting: Keeping the API Available Under Abuse

What rate limiting should protect

Rate limiting is about availability and cost control. It should protect against: credential stuffing and brute force on login-like mutations, scraping and enumeration of IDs, abusive clients that retry aggressively, and distributed traffic spikes that overwhelm downstream dependencies. GraphQL adds a twist: one request can be “cheap” or “expensive” depending on the operation and variables, so rate limiting often needs multiple dimensions: requests per time window, operation-based limits, and resource-based limits (for example, per resolver or per data source).

Step-by-step: Choose identifiers and apply layered limits

Effective rate limiting starts with choosing the right identity keys. IP-only limits are easy but unreliable behind NATs and mobile networks, and they are weak against botnets. User-based limits are better but require authentication. In practice, use layered keys and apply the strictest applicable limit.

- Step 1: Define actor keys. Use a combination such as: authenticated user ID (if present), API key ID (if present), and a normalized client IP (taking proxies into account safely).

- Step 2: Apply global request limits. Example: 60 requests per minute per user, 20 per minute per IP for unauthenticated traffic.

- Step 3: Apply operation-specific limits. Example: password reset mutation 3 per hour per IP and 3 per hour per email hash; login mutation 10 per minute per IP and 10 per minute per username hash.

- Step 4: Apply burst control. Use token bucket or leaky bucket algorithms to allow short bursts but cap sustained rate.

- Step 5: Return standard signals. Use HTTP 429 for transport-level rate limits, and include retry hints (like

Retry-After) when possible.

// Example: rate limit key selection (pseudocode) function rateLimitKey(ctx) { if (ctx.actor?.id) return `user:${ctx.actor.id}`; if (ctx.apiKey?.id) return `key:${ctx.apiKey.id}`; return `ip:${ctx.clientIp}`; } async function enforceLimit({ ctx, limitName, max, windowSec }) { const key = `${limitName}:${rateLimitKey(ctx)}`; const allowed = await redisSlidingWindowAllow(key, max, windowSec); if (!allowed) { throw new TooManyRequestsError("Too many requests"); } }Operation-aware limiting using operation name and persisted IDs

GraphQL requests can include an operationName. If you trust it blindly, attackers can spoof it to bypass per-operation limits. Prefer identifying operations by a persisted query ID or by hashing the normalized document server-side. If you do accept operationName, treat it as a hint and still bind limits to the actual document hash.

A practical pattern is: compute a stable signature of the operation (for example, SHA-256 of the printed AST with whitespace normalized), then apply limits per signature. This prevents an attacker from renaming the operation to evade controls.

Resolver-level throttles and dependency protection

Even with request-level rate limits, a single operation might hammer a fragile downstream system (like a third-party API). Add dependency-aware throttles: cap concurrent calls, enforce per-dependency QPS, and use circuit breakers. This is not only about malicious traffic; it also prevents cascading failures during partial outages.

- Limit concurrency per resolver or per data source (for example, at most 50 concurrent calls to a partner API).

- Use timeouts and fail fast when budgets are exceeded.

- Cache or deduplicate identical outbound calls within a request when possible.

- Apply stricter limits to unauthenticated traffic and to operations that are known to be expensive.

// Example: dependency semaphore (pseudocode) const partnerSemaphore = new Semaphore(50); async function callPartnerSafely(fn) { const release = await partnerSemaphore.acquire(); try { return await withTimeout(fn(), 1500); } finally { release(); } }Combining rate limiting with safe error responses

Rate limiting responses should not leak sensitive information. For example, if you rate limit by email hash on password reset, do not return different messages for “email exists” vs “email does not exist,” and do not reveal which key triggered the limit. Keep the client message generic and rely on logs and metrics for diagnosis.

Observability for security controls

Hardening controls are only effective if you can see them working. Track metrics such as: introspection blocks per minute, validation failures per operation, rate limit denials by key type (user, key, IP), and top operation signatures by volume. Store security-relevant logs with care: avoid logging secrets, but include enough context (operation signature, actor ID, request ID) to investigate abuse. Use sampling for high-volume events to control log costs while preserving signal.

Putting It Together: A Hardened Request Lifecycle

A practical way to implement these controls is to treat them as a pipeline that runs before and during execution. First, identify the actor and compute a request fingerprint. Next, enforce global and operation-specific rate limits. Then parse and validate the document, blocking introspection when not allowed. Validate and normalize variables and input objects at the operation boundary. During execution, apply dependency throttles and safe outbound call patterns. Finally, emit structured security telemetry. This layered approach ensures that even if one control is bypassed or misconfigured, other controls still reduce risk.