Threat Model for Hypermedia Apps: What Changes with HTMX

What to protect and why: With HTMX, many interactions that used to be full-page POST/PUT/DELETE requests become fragment requests initiated by attributes like hx-post or hx-delete. The browser still sends cookies automatically, so the core web threats remain: cross-site request forgery (CSRF), session fixation, credential theft, and authorization bypass. The difference is operational: you will have more small endpoints, more partial responses, and more UI states that can fail mid-flow. Security and reliability depend on consistent server-side enforcement and predictable client behavior when requests succeed, fail, or are retried.

Principle: Treat every HTMX request as a normal HTTP request. Do not rely on “it’s just a fragment” as a security boundary. Authorization, CSRF validation, and input validation must run exactly the same as for full-page requests. When you return partial HTML, ensure it is safe to render in the target container and does not leak data across users.

CSRF Protection: Cookies Make You Vulnerable by Default

Concept: CSRF happens when a malicious site causes a victim’s browser to send an authenticated request to your site (because cookies are automatically attached). HTMX does not create CSRF; it simply makes it easy to send state-changing requests from the page. Any endpoint that changes server state (create/update/delete) must require a CSRF token (or an equivalent defense such as SameSite cookies plus additional checks, depending on your risk profile).

Where CSRF shows up in HTMX: A button with hx-post is still a POST. If it relies only on a session cookie, it is CSRFable. The fix is the same as classic server-rendered apps: include a token in the request and validate it server-side.

Step-by-step: Add CSRF tokens to all HTMX requests

Step 1 — Generate a token per session (or per request): On the server, generate a cryptographically strong token and store it in the session (or sign it). Render it into the HTML as a meta tag or hidden input. A common pattern is a meta tag so it’s available globally.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

<meta name="csrf-token" content="{{ csrf_token }}">Step 2 — Send the token with HTMX requests: HTMX can attach headers to every request using hx-headers. You can put it on <body> (or a high-level container) so it applies everywhere.

<body hx-headers='{"X-CSRF-Token": "{{ csrf_token }}"}'> ... </body>Alternative — Use a hidden field for form posts: If you are submitting a form via HTMX, include a hidden input and validate it server-side. This is especially useful if your framework already expects csrf_token in the form body.

<form hx-post="/account/email" hx-target="#email-panel"> <input type="hidden" name="csrf_token" value="{{ csrf_token }}"> <input type="email" name="email"> <button type="submit">Save</button></form>Step 3 — Validate on the server for every unsafe method: Validate CSRF for POST/PUT/PATCH/DELETE. If invalid, return 403. For HTMX, you can return a fragment that shows an error banner, but do not leak token details.

// Pseudocode middleware

if method in [POST, PUT, PATCH, DELETE]:

token = header["X-CSRF-Token"] or form["csrf_token"]

if not valid(token, session):

return 403Step 4 — Handle token rotation and expired sessions: If the session expires, HTMX requests will start failing. Decide a consistent behavior: return 401 with a login fragment, or 302 to a login page (but be careful: redirects inside fragment swaps can confuse the UI). A robust pattern is to return 401 and use an HTMX event handler to trigger a full-page redirect.

Authentication Flows: Login, Re-Auth, and Partial Requests

Concept: Authentication is not only “login page then app.” In real systems, sessions expire, users open multiple tabs, and sensitive actions may require re-authentication. With HTMX, these events often happen during fragment requests, so you need a predictable contract: what status codes mean, what HTML is returned, and when the browser should navigate.

Key rule: Never assume that because a user can see a button, they are authorized to perform the action. Always enforce authorization on the server. HTMX can improve UX, but it cannot be the gatekeeper.

Step-by-step: Define a consistent response strategy for auth failures

Step 1 — Choose status codes: Use 401 Unauthorized for unauthenticated, 403 Forbidden for authenticated but not allowed. This distinction matters because the UI response differs: 401 should usually lead to login; 403 should show an access-denied message.

Step 2 — Decide “fragment vs full navigation” behavior: For HTMX requests, you often want to redirect the whole page to login, not swap a login form into a random panel. A common approach: return 401 and include a header that tells the client where to go, then handle it centrally.

// Server response headers (example)

Status: 401

HX-Redirect: /login?next=/settingsStep 3 — Centralize client handling: Add a small script that listens for HTMX events and reacts to 401/403. This keeps individual components simple.

<script>

document.body.addEventListener('htmx:responseError', function (evt) {

const xhr = evt.detail.xhr;

if (xhr.status === 401) {

const redirect = xhr.getResponseHeader('HX-Redirect');

window.location.href = redirect || '/login';

}

});

</script>Step 4 — Re-authentication for sensitive actions: For actions like changing password or exporting data, require “recent login.” If not recent, return 409 or 403 with a fragment that prompts for password re-entry. The fragment can be loaded into a modal or a dedicated panel, but the server must enforce the rule.

Authorization and Data Leakage: Fragment Endpoints Must Be Scoped

Concept: Fragment endpoints often accept IDs (e.g., /orders/123/row). If authorization checks are inconsistent across endpoints, attackers can enumerate IDs and retrieve fragments they should not see. This is a classic insecure direct object reference (IDOR) risk, amplified by the number of small endpoints in hypermedia apps.

Practical rule: Every endpoint that returns user-specific HTML must verify ownership/permissions for the referenced resource. Do not rely on “the page that links here is protected.” Attackers call endpoints directly.

Step-by-step: Make authorization checks uniform

Step 1 — Create a single authorization function per resource: For example, can_view_order(user, order) and can_edit_order(user, order). Use it in both full-page and fragment handlers.

// Pseudocode

order = findOrder(orderId)

if not canViewOrder(currentUser, order):

return 404 // or 403, depending on your policy

return renderPartial("order_row", order)Step 2 — Prefer 404 for unauthorized resource existence hiding: In many apps, returning 404 for “not yours” reduces information leakage. Use 403 when you want to explicitly tell the user they lack permission (e.g., internal tools).

Step 3 — Avoid embedding secrets in fragments: Be careful with partial templates that include hidden fields, internal IDs, or debug info. HTMX makes it easy to swap HTML; it also makes it easy to accidentally expose data in a fragment that was previously only present on a protected full page.

Idempotency: Reliable Writes Under Retries, Double Clicks, and Network Glitches

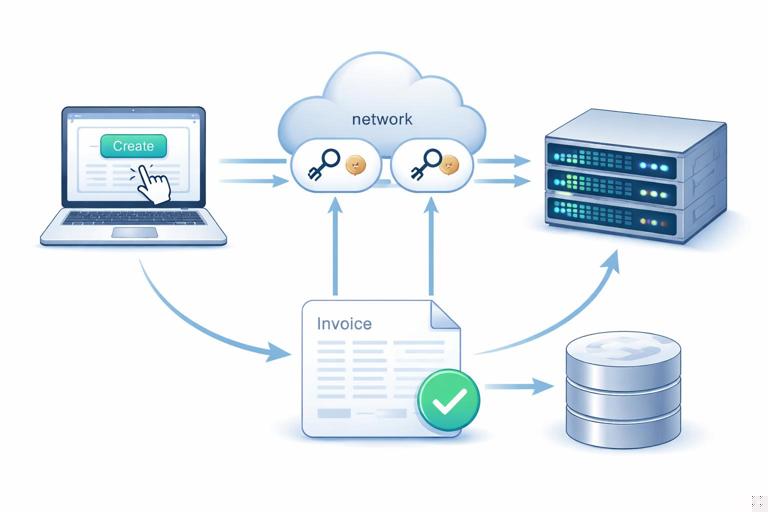

Concept: Idempotency means repeating the same request has the same effect as doing it once. This matters because users double-click, mobile networks drop, and browsers retry. HTMX also introduces patterns where a request might be triggered again due to re-rendering or user actions. Without idempotency, you can create duplicate records, double-charge payments, or apply the same mutation twice.

Two categories of actions: (1) Naturally idempotent updates (e.g., “set status to archived”), and (2) non-idempotent creations (e.g., “create invoice”). For category (2), add an idempotency key.

Step-by-step: Implement idempotency keys for create actions

Step 1 — Generate an idempotency key on the client: You can generate a UUID in the browser and include it as a header or hidden input. Alpine.js can hold it in component state so it persists across retries within the same view.

<div x-data="{ idem: crypto.randomUUID() }">

<form hx-post="/invoices" hx-target="#invoice-result" hx-headers='{"Idempotency-Key": "' + idem + '"}'>

<input name="amount" type="number">

<button type="submit">Create invoice</button>

</form>

</div>Note: If you prefer not to build JSON strings in attributes, send the key as a hidden input and read it server-side. The important part is that the key is stable for that “attempt.”

Step 2 — Store the key server-side with the result: When the server receives a create request with an idempotency key, it checks whether it has already processed that key for the same user and endpoint. If yes, return the previously created resource (or the same fragment) instead of creating a new one.

// Pseudocode

key = request.header["Idempotency-Key"]

existing = findIdempotencyRecord(userId, key)

if existing:

return existing.response

result = createInvoice(...)

storeIdempotencyRecord(userId, key, responseFor(result))

return responseFor(result)Step 3 — Define the scope and TTL: Scope keys by user and operation (and sometimes by request body hash). Set a TTL (e.g., 24 hours) to prevent unbounded growth. For payment-like operations, keep longer and store enough metadata to audit.

Step 4 — Make UI resilient to repeated success responses: If the same response comes back twice, the UI should not duplicate rows or re-run animations in a way that confuses users. Prefer swapping a single target container rather than “append” for create confirmations, unless you can deduplicate client-side.

Safe Retries and Concurrency: Prevent Lost Updates

Concept: Reliability issues are not only duplicates; they are also lost updates when two tabs edit the same resource. A hypermedia UI can make this more frequent because users can keep multiple panels open and submit changes independently.

Practical approach: Use optimistic concurrency control with a version field (or ETag). The server rejects updates if the version is stale, and returns an HTML fragment that explains the conflict and offers a refresh.

Step-by-step: Add a version token to edit forms

Step 1 — Render a version in the form: Include a hidden field like version (or updated_at timestamp) that represents the last known state.

<form hx-put="/profile" hx-target="#profile-panel">

<input type="hidden" name="version" value="{{ profile.version }}">

<input name="display_name" value="{{ profile.display_name }}">

<button>Save</button>

</form>Step 2 — Validate on update: If the submitted version doesn’t match the current version in the database, return 409 Conflict and a fragment that shows the conflict and a “Reload” action.

// Pseudocode

if form.version != db.profile.version:

return 409 with renderPartial("conflict_notice", current=db.profile)Step 3 — Provide a reload path: The conflict fragment can include a button that triggers an hx-get to reload the latest form, or a full-page refresh if the state is complex.

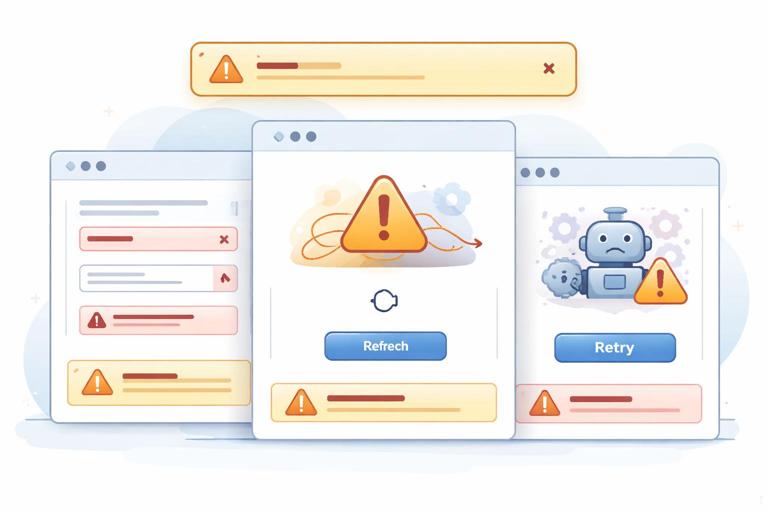

Error States: Designing Predictable Failures for Fragment Swaps

Concept: In a traditional full-page app, an error often means “show an error page.” In an HTMX app, errors can happen in small regions: a sidebar fails to load, a save fails, or a background refresh returns invalid HTML. If you don’t design error states, users see stale UI, missing controls, or silent failures.

Goal: Every request should have a defined behavior for (1) success, (2) validation errors, (3) auth errors, (4) server errors, and (5) network timeouts. The UI should show a clear message in the right place and offer a next action.

Step-by-step: Handle 4xx/5xx responses intentionally

Step 1 — Return meaningful status codes: Use 422 Unprocessable Entity for validation errors, 409 for conflicts, 500 for unexpected server errors. This allows consistent client hooks and logging.

Step 2 — Return HTML fragments for recoverable errors: For example, on 422, return the form fragment with inline errors. On 409, return a conflict prompt. On 500, return a small error panel with a retry button.

<div class="error">

<p>We couldn’t save your changes due to a server error.</p>

<button hx-post="/profile" hx-include="closest form" hx-target="#profile-panel">Retry</button>

</div>Step 3 — Use an error target for global banners: Some errors should not replace the component content (e.g., “session expired”). Decide a global container (like #flash) and, when appropriate, swap into it. You can do this by returning an out-of-band swap fragment so the banner updates without disrupting the local component.

<div id="flash" hx-swap-oob="true">

<div class="flash flash-error">Your session expired. Please sign in again.</div>

</div>Step 4 — Provide a retry strategy for transient failures: For transient network errors, a “Retry” button is often enough. For auto-refresh panels, consider exponential backoff on the server side (by reducing refresh frequency) or on the client side (by pausing refresh when errors occur). If you implement automatic retries, cap them and always provide a manual retry control.

Input Trust Boundaries: Don’t Let Fragments Become an Injection Vector

Concept: HTMX encourages returning HTML. That HTML is executed by the browser as markup, so any server-side HTML injection becomes a client-side XSS risk. The defense is the same as server-rendered apps: escape untrusted data in templates, sanitize rich text, and avoid concatenating HTML strings.

Practical checks: Ensure your templating engine auto-escapes by default. For user-generated content that must include formatting, use a sanitizer allowlist. Avoid returning raw error messages from exceptions; map them to user-safe messages and log the details server-side.

Operational Reliability: Observability for Many Small Requests

Concept: HTMX apps can generate more requests than full-page navigation, especially when multiple regions update independently. Reliability requires being able to answer: Which endpoint is failing? For which users? Is it a CSRF issue, auth expiry, or a server error?

Practical approach: Add request IDs and log them. Include the request ID in error fragments so support can correlate a user report with server logs. If you use idempotency keys, log them too.

<div class="error">

<p>Something went wrong. Reference: {{ request_id }}</p>

</div>Server logging checklist: Log method, path, user ID (if authenticated), status code, latency, and whether the request was an HTMX request (often detectable via the HX-Request header). This helps you distinguish fragment failures from full-page failures and tune caching, timeouts, and rate limits appropriately.