What hashing is (and what it is not)

Hashing is a one-way transformation that maps input data of arbitrary length to a fixed-length digest. A cryptographic hash function is designed so that small changes in input produce unpredictable changes in output, and it is computationally infeasible to find two different inputs with the same digest (collision resistance) or to recover an input from its digest (preimage resistance). Hashing is not encryption: encryption is reversible with a key, while hashing is intentionally irreversible and uses no secret key.

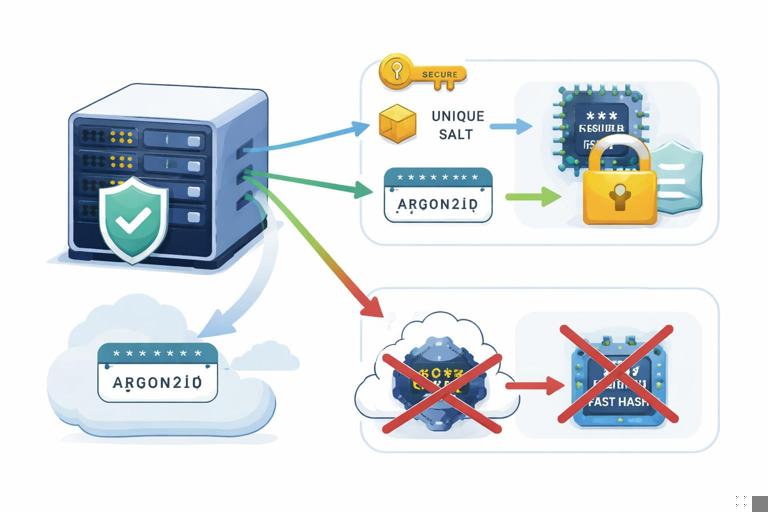

In practice, developers use hashing for integrity checks, content addressing, and—most importantly in this chapter—password storage. The key idea is that you should never store a password itself, and you should avoid storing a fast hash of a password. Instead, you store a password verifier derived using a slow, memory-hard password hashing function with a unique salt per account.

Fast hashes vs password hashing functions

General-purpose cryptographic hashes like SHA-256, SHA-512, and BLAKE2 are optimized to be fast on CPUs and often on GPUs/ASICs. That speed is great for integrity and signatures, but it is exactly what you do not want for password storage. Attackers who obtain your password database can try billions of guesses per second if your verifier is based on a fast hash.

Password hashing functions (PHFs) are deliberately expensive. They increase the cost per guess by using many iterations and, ideally, significant memory. This makes offline cracking far more expensive and reduces the advantage of specialized hardware. Modern choices include Argon2id (recommended in many new systems), scrypt (still widely used), and bcrypt (older but common; less memory-hard).

Rule of thumb

- Use SHA-256/SHA-512/BLAKE2 for integrity and general hashing tasks.

- Use Argon2id (preferred), scrypt, or bcrypt for passwords.

- Never use a plain fast hash (e.g., SHA-256(password)) as a password storage scheme.

Salts: what they do and what they do not do

A salt is a unique, random value stored alongside the password verifier. During verification, you recompute the verifier using the stored salt and compare. Salts prevent attackers from using precomputed tables (like rainbow tables) and ensure that identical passwords result in different verifiers across accounts. Salts also prevent an attacker from immediately spotting users who share the same password by comparing stored verifiers.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Salts do not make weak passwords strong, and they do not stop offline guessing if the attacker has the database. They simply ensure the attacker must attack each account independently and cannot reuse precomputation across your entire user base.

Salt requirements

- Unique per password (per account, per credential).

- Random (generated with a cryptographically secure RNG).

- Stored in plaintext next to the verifier (this is normal).

- Length: typically 16 bytes or more.

Pepper: a server-side secret to reduce blast radius

A pepper is an additional secret value mixed into the password hashing process that is not stored in the database. Unlike a salt, the pepper must be kept secret (for example in an HSM, a secrets manager, or environment-protected configuration). If an attacker steals only the database, the pepper forces them to also obtain the application secret before they can verify guesses offline.

Pepper is not a replacement for a proper PHF. It is a defense-in-depth measure that can meaningfully reduce damage in common breach scenarios (database exfiltration without full server compromise). If the attacker compromises the application servers too, pepper may be exposed, so you still need strong password hashing and online defenses.

Pepper patterns

- Append/prepend pepper to the password before hashing: PHF(password || pepper, salt).

- Use an HMAC as a pre-hash: PHF(HMAC(pepper, password), salt). This can normalize input and avoid some edge cases with encoding.

Choosing Argon2id parameters (practical guidance)

Argon2id is designed to resist GPU/ASIC cracking by requiring memory and CPU time. It has three primary parameters: memory cost, time cost (iterations), and parallelism. The right parameters depend on your server resources and latency budget. Your goal is to make each password verification “expensive enough” to slow attackers, while still allowing legitimate logins and password changes at your expected scale.

Step-by-step: calibrate parameters on your production-like hardware

Step 1: pick a target latency per hash. Common targets are 100–300 ms for interactive logins, sometimes higher for password changes. The right value depends on your traffic and infrastructure.

Step 2: start with memory. Choose a memory cost that is significant but safe for concurrency. For example, 64 MiB per hash might be fine for a small service, while a high-traffic service may choose 16–32 MiB to avoid memory exhaustion under load.

Step 3: set time cost. Increase iterations until you hit your target latency on your slowest production node. Keep some headroom for peak load.

Step 4: set parallelism. Use a small value (e.g., 1–4). Higher parallelism can help on multi-core systems but also increases resource contention.

Step 5: record parameters with the hash. Store the algorithm and parameters alongside the verifier so you can upgrade later without breaking existing accounts.

Example encoded verifier format

Many libraries output a self-describing string that includes algorithm and parameters. Store it as-is.

$argon2id$v=19$m=65536,t=3,p=2$BASE64_SALT$BASE64_HASHImplementing password storage correctly

The safest approach is to use a well-reviewed library that provides a high-level API for password hashing and verification. Avoid rolling your own encoding, parameter parsing, or comparison logic unless you must. The implementation details that often go wrong are: using the wrong primitive (fast hash), reusing salts, truncating hashes, and leaking timing information during comparison.

Step-by-step: account creation (registration)

Step 1: normalize input carefully. Treat passwords as opaque byte sequences. If your system accepts Unicode, define a consistent encoding (typically UTF-8) and do not apply lossy transformations (like lowercasing). Be cautious with “trim whitespace” rules; they can surprise users and reduce password space.

Step 2: generate a random salt. Use a CSPRNG and generate at least 16 bytes.

Step 3: compute the password hash using a PHF. Use Argon2id/scrypt/bcrypt with calibrated parameters. Optionally incorporate a pepper (ideally via HMAC pre-hash).

Step 4: store the encoded verifier. Store the PHF output string (including parameters and salt) in your users table. Do not store the raw password. Do not store a separate “password hint” or reversible encrypted password.

Step-by-step: login verification

Step 1: fetch the stored verifier by username/email. If the account does not exist, use a dummy verifier and perform a hash anyway to reduce user enumeration via timing (also return a generic error message).

Step 2: recompute and verify. Use the library’s verify function. Ensure constant-time comparison is used internally (most libraries do this).

Step 3: on success, consider rehashing. If your parameters have been upgraded since the verifier was created, rehash the password with the new parameters and update the stored verifier.

Pseudocode (language-agnostic)

// Registration: store verifier (self-describing string) in DB

salt = CSPRNG(16)

pre = HMAC(pepper, password_bytes) // optional but recommended

verifier = Argon2id(pre, salt, m=65536, t=3, p=2)

DB.store(user_id, verifier)

// Login: verify

verifier = DB.load(user_id)

pre = HMAC(pepper, password_bytes)

if Argon2id_verify(verifier, pre) == true:

if needs_rehash(verifier, current_params):

new_verifier = Argon2id(pre, new_salt, current_params)

DB.update(user_id, new_verifier)

allow_login()

else:

deny_login_generic()Credential abuse: what attackers do after (or without) a breach

Even if your password storage is excellent, attackers can still compromise accounts through credential abuse. The most common patterns are credential stuffing (reusing leaked username/password pairs from other sites), password spraying (trying a few common passwords across many accounts), and brute-force attempts against a single account. These are online attacks: the attacker interacts with your login endpoint and is constrained by your defenses and rate limits.

Credential abuse defenses must be designed to avoid locking out legitimate users while still making automated abuse expensive. You also need to assume attackers will distribute attempts across IPs, use residential proxies, mimic browsers, and target password reset flows.

Rate limiting and throttling that actually works

Simple per-IP rate limiting is not enough because attackers can rotate IPs. You need layered throttling keyed on multiple signals: account identifier, IP, device fingerprint (carefully), and global system health. The goal is to reduce the attacker’s guess rate while keeping user experience acceptable.

Step-by-step: layered login throttling

Step 1: per-account throttling. Track failed attempts per account and apply exponential backoff (e.g., 1s, 2s, 4s, 8s…) with a cap. This directly targets brute-force on a single account.

Step 2: per-IP and per-subnet throttling. Apply limits per IP and optionally /24 or ASN-level heuristics. This helps against naive attacks and reduces load.

Step 3: global abuse controls. If the system detects a spike in failures, tighten thresholds temporarily, require additional verification, or degrade responses.

Step 4: make responses uniform. Use generic error messages (“Invalid credentials”) and similar response times for non-existent vs existent accounts to reduce enumeration.

Implementation notes

- Store counters in a fast shared store (Redis/memcached) with TTLs.

- Use sliding windows or token buckets rather than fixed windows to avoid edge effects.

- Be careful with hard lockouts; they can be abused for denial-of-service against users.

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) and step-up checks

MFA is one of the strongest mitigations against credential stuffing because it breaks the “password alone” assumption. However, not all MFA is equal. SMS is vulnerable to SIM swap and interception; TOTP apps are better; phishing-resistant methods like WebAuthn/FIDO2 are best for high-value accounts. A practical approach is to offer MFA broadly and require stronger methods for admins, financial actions, or suspicious logins.

Step-up authentication means you do not always require MFA, but you require it when risk is higher: new device, unusual location, repeated failures, or sensitive actions like changing email, disabling MFA, or initiating payouts.

Step-by-step: deploy MFA without breaking users

Step 1: enroll. Provide a clear enrollment flow and generate recovery codes. Store only what you must (e.g., TOTP secret encrypted at rest; WebAuthn public keys).

Step 2: enforce for privileged roles. Require MFA for admins and for access to sensitive dashboards.

Step 3: add step-up triggers. Require MFA when risk signals fire (new device, impossible travel, high failure rate).

Step 4: protect MFA reset. Ensure account recovery does not become the weakest link; require additional verification and cooldowns for changing MFA settings.

Detecting credential stuffing and password spraying

Detection is about recognizing patterns: many accounts targeted from one source, many sources targeting one account, or a low success rate with high volume. You should log enough to investigate without collecting unnecessary sensitive data. At minimum, log timestamps, account identifier (or a stable hash of it), IP, user agent, outcome, and reason codes (rate limited, MFA required, wrong password).

Practical signals

- High ratio of failed logins to successful logins from an IP or ASN.

- Many distinct usernames attempted from one IP in a short window (spraying).

- Many IPs attempting the same username (targeted attack).

- Repeated attempts with common passwords across many accounts.

Response playbook (automatable)

- Introduce progressive challenges: CAPTCHA or proof-of-work after suspicious patterns.

- Require MFA or step-up for the targeted accounts.

- Temporarily block abusive IPs/ASNs with careful review to avoid collateral damage.

- Notify users when there are repeated failed attempts on their account.

Password reset and account recovery: common failure points

Attackers often bypass strong password storage by attacking password reset flows. Reset endpoints can leak whether an email exists, allow token guessing, or be abused via intercepted email. The reset token is effectively a temporary password, so it must be generated securely, expire quickly, and be single-use.

Step-by-step: secure password reset tokens

Step 1: generate a high-entropy random token. Use at least 128 bits from a CSPRNG and encode it (base64url) for transport.

Step 2: store only a hash of the token. Treat reset tokens like passwords: store token_hash = H(token) (fast hash is fine here because token is random and high entropy), plus user_id, expiry, and used_at. If the database leaks, attackers should not be able to use reset tokens.

Step 3: set short expiration and single-use. Typical expiry is 10–30 minutes. Mark tokens as used immediately upon successful reset.

Step 4: avoid account enumeration. Always respond with the same message (“If the account exists, we sent an email”). Rate limit reset requests per account and per IP.

Step 5: invalidate sessions and rotate credentials. After password reset, revoke existing sessions and refresh tokens, and consider notifying the user.

Pseudocode for reset token storage

token = base64url(CSPRNG(32)) // 256-bit token

token_hash = SHA-256(token)

DB.store_reset(user_id, token_hash, expires_at, used_at=null)

Email.send(link_with_token)

// When user submits token

token_hash = SHA-256(token)

row = DB.find_reset(user_id, token_hash)

if row exists and not used and not expired:

mark_used(row)

set_new_password(user_id)

revoke_sessions(user_id)

else:

deny_generic()Safe comparisons and side-channel basics in credential checks

Credential verification can leak information through timing if comparisons exit early on mismatch. For password verifiers, use library verification functions that perform constant-time comparisons. For reset tokens or API keys, use constant-time comparison functions provided by your platform. Also ensure you do not accidentally leak whether a user exists through different code paths, different error messages, or noticeably different response times.

Checklist

- Use constant-time compare for secrets (tokens, API keys, session IDs).

- Return generic errors for login and reset flows.

- Perform similar work for “user not found” as for “wrong password” (within reason).

- Log internally with detailed reason codes, but do not expose them to clients.

Upgrading password hashes over time (rehashing strategy)

Hardware gets faster and your security requirements change. A robust system anticipates this by storing self-describing verifiers and rehashing opportunistically. When a user logs in successfully, you can check whether the stored verifier uses outdated parameters or an older algorithm and then rehash with the current configuration.

Step-by-step: opportunistic rehash

Step 1: define current parameters. Keep them in configuration and version them.

Step 2: on successful login, check needs_rehash. Many libraries provide this helper; otherwise parse the encoded string.

Step 3: rehash and update atomically. Update the stored verifier in the same transaction as login session creation if possible.

Step 4: plan for forced resets only when necessary. If you must migrate from a broken scheme (e.g., unsalted fast hashes), you may need to require password resets for users who do not log in during the migration window.

Operational hardening: logging, monitoring, and secrets handling

Password hashing and credential defenses are not only code problems. Operational mistakes—like logging passwords, leaking reset tokens in URLs to third-party analytics, or exposing peppers in debug endpoints—can undo strong cryptography. Treat all authentication artifacts as sensitive: passwords, reset tokens, session tokens, MFA recovery codes, and API keys.

Practical do’s and don’ts

- Do not log passwords or full reset URLs; if you must log, redact tokens.

- Keep pepper in a secrets manager; rotate it with a plan (rotation may require rehashing or dual-pepper verification during transition).

- Protect authentication endpoints with WAF rules and anomaly detection.

- Monitor for spikes in failed logins, reset requests, and MFA failures.

- Ensure database backups are protected; a backup leak is a database leak.