What “resolver architecture” means in practice

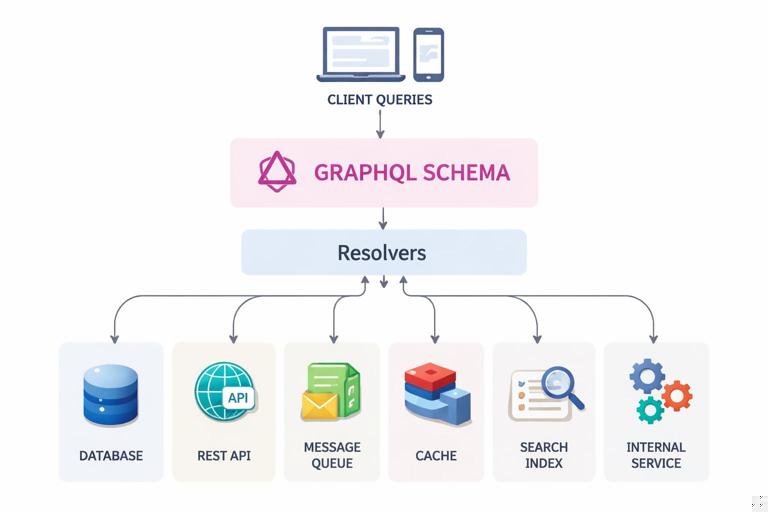

Resolver architecture is the set of patterns and components you use to turn a GraphQL operation into concrete data access and computation. A schema describes what clients can ask for; resolvers decide how to fetch it, how to combine multiple sources, how to enforce authorization, and how to keep performance predictable. Good resolver architecture is less about writing many resolver functions and more about designing a consistent mapping layer between schema fields and your underlying systems (databases, REST services, message queues, caches, search indexes, and internal libraries).

In a mature codebase, resolvers are thin coordinators. They validate request context, call a domain service or data access layer, and return results in the shape the schema expects. The “shape” is important: GraphQL encourages nested selection sets, and naive resolvers often trigger N+1 queries or repeated remote calls. Resolver architecture addresses this by introducing batching, caching, and clear boundaries between field resolvers and data source adapters.

Resolver execution model and why it drives architecture

GraphQL executes resolvers top-down following the query’s selection set. For each field, GraphQL calls a resolver with four common inputs: parent (the object returned by the previous level), args (field arguments), context (request-scoped dependencies and auth info), and info (AST and execution metadata). The key architectural implication is that sibling fields can be resolved independently and potentially in parallel, but nested fields depend on their parent object. If your parent resolver returns only IDs, child resolvers may need to fetch full objects; if your parent returns full objects, child resolvers can often be trivial property accessors.

This leads to a core design decision: decide where the “fetch” happens. You can fetch eagerly at higher levels (returning rich objects early) or lazily at lower levels (fetching per field). Eager fetching can reduce resolver count but may overfetch from your backend; lazy fetching can align with GraphQL’s selective nature but risks N+1. A good architecture mixes both: fetch coarse-grained aggregates at parent levels and use batched loaders for child-level lookups.

Layering: resolvers, domain services, and data sources

A practical layering model separates concerns into three tiers. First, resolvers are the GraphQL boundary: they translate GraphQL args into domain-friendly inputs, enforce field-level policies, and orchestrate calls. Second, domain services implement business use cases (for example, “list orders for customer with totals”), independent of GraphQL. Third, data sources (repositories, REST clients, SDK wrappers) talk to actual storage or remote systems. This separation keeps schema changes from leaking into persistence code and makes it easier to reuse business logic across GraphQL, background jobs, and other APIs.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

In code, the resolver should rarely build SQL, craft HTTP requests, or know table names. Instead, it calls something like context.services.orderService.listOrdersForCustomer(customerId, options). The service might call repositories and other services, and repositories might use query builders or ORM. This structure also makes testing easier: resolver tests can mock services, service tests can mock repositories, and repository tests can run against a test database.

Mapping schema fields to data sources: a repeatable workflow

Mapping a schema to data sources is a design activity: for each field, decide the authoritative source, the access path, and the performance strategy. A repeatable workflow helps you avoid ad-hoc resolver growth.

Step 1: Classify each field by ownership and volatility

For every object type field, decide whether it is stored (directly persisted), derived (computed from other fields), federated (comes from another service), or externalized (comes from a third-party API). Stored fields typically map to a database column or document property. Derived fields might be totals, statuses, or formatted values. Federated fields might require a call to another internal service. Externalized fields often need rate limiting and caching.

Step 2: Choose the “root fetch” for each query entry point

For each query field (entry point), decide what you fetch first. For example, a query that returns a list of products might fetch product rows from a database with only the columns needed for common fields plus IDs for related objects. The root fetch should be designed to support typical selection sets efficiently. If clients frequently request product with price and inventory, you might fetch price from the pricing service in batch at the list level rather than per product field.

Step 3: Define child field resolution strategy

For each nested field, decide whether it can be resolved by simple property access (already present on the parent), by a batched lookup (DataLoader pattern), by a service call that can accept multiple keys, or by preloading in the parent resolver. The rule of thumb: if a child field requires I/O and can be requested for many parents, use batching. If it is cheap and purely computed, compute it in the field resolver. If it is expensive and rarely requested, keep it lazy and cache it.

Step 4: Add cross-cutting policies at the right level

Authorization, logging, tracing, and caching should be consistent. Decide which policies belong in middleware (wrapping all resolvers), which belong in specific resolvers (field-level checks), and which belong in services (business rules). For example, “user must own the order” is a business rule and belongs in the order service; “only admins can see internalCost field” is a field-level rule and belongs in that field resolver or a directive/middleware that runs on that field.

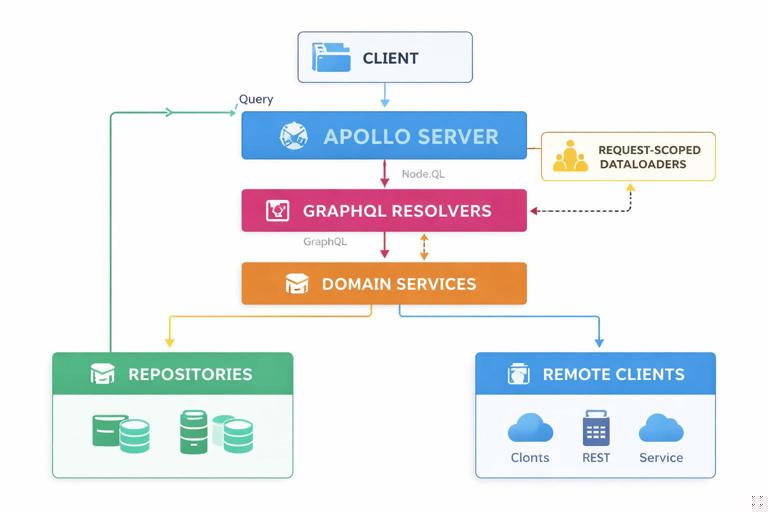

Example architecture: Node.js Apollo Server with services and loaders

The following example shows a common structure: resolvers call services; services call repositories and remote clients; DataLoaders batch child lookups. The key is that loaders are request-scoped (created per request) so they can batch within a single operation and avoid leaking cached data across users.

// context.ts (request-scoped dependencies) export function buildContext({ req }) { const user = authenticate(req); const db = makeDbClient(); const repos = { productRepo: new ProductRepository(db), reviewRepo: new ReviewRepository(db) }; const clients = { inventoryClient: new InventoryClient(process.env.INVENTORY_URL) }; const services = { productService: new ProductService(repos, clients) }; const loaders = { reviewsByProductId: new DataLoader(async (productIds) => { const rows = await repos.reviewRepo.findByProductIds(productIds); const map = new Map(productIds.map(id => [id, []])); for (const r of rows) map.get(r.productId).push(r); return productIds.map(id => map.get(id)); }), inventoryBySku: new DataLoader(async (skus) => { const items = await clients.inventoryClient.batchGetBySku(skus); const map = new Map(items.map(i => [i.sku, i])); return skus.map(sku => map.get(sku) || null); }) }; return { user, services, loaders }; }With this context, resolvers stay small. They translate args, call services, and use loaders for nested fields.

// resolvers.ts export const resolvers = { Query: { products: async (_parent, args, ctx) => { return ctx.services.productService.listProducts({ search: args.search, limit: args.limit }); }, product: async (_parent, args, ctx) => { return ctx.services.productService.getProductById(args.id); } }, Product: { // stored field: can be default resolver if parent has 'name' name: (p) => p.name, // derived field: computed locally displayPrice: (p) => formatMoney(p.priceCents, p.currency), // federated/external field: batch via loader inventory: async (p, _args, ctx) => { return ctx.loaders.inventoryBySku.load(p.sku); }, // one-to-many: batch reviews by product id reviews: async (p, _args, ctx) => { return ctx.loaders.reviewsByProductId.load(p.id); } } };Notice how the Product field resolvers do not reach into the database directly. They either read from the parent object (already fetched) or use a loader that is backed by a repository/client. This makes it easy to change the underlying storage without rewriting GraphQL logic.

Designing parent objects: “return enough to resolve children”

A subtle but powerful technique is to shape the parent object returned by a resolver so that child resolvers can avoid extra calls. For example, if Product.inventory needs sku, ensure the product root fetch includes sku. If Order.customer needs customerId, include customerId. This sounds obvious, but in practice teams often return partial objects that lack the keys needed for nested fields, forcing child resolvers to refetch the same entity just to get identifiers.

A practical approach is to define internal “resolver models” (sometimes called view models) that contain the minimal set of fields needed for downstream resolution. These are not the same as your database models; they are tailored to GraphQL execution. For instance, a ProductResolverModel might include id, sku, name, priceCents, currency, and maybe categoryIds, even if the database table has many more columns.

Batching and caching with DataLoader: mapping at scale

When mapping nested fields to data sources, the most common performance pitfall is N+1: a list query returns N parent objects, and each child field triggers an additional query. DataLoader addresses this by collecting keys during execution and issuing a single batched call per field per request. Architecturally, this means your repositories and clients should expose batch methods (findByIds, findByForeignKeys, batchGetBySku) so loaders can call them efficiently.

To implement batching correctly, your batch function must return results in the same order as the keys. It must also handle missing values (return null or empty arrays). For one-to-many relationships, return arrays per key. For many-to-one, return a single object or null. Keep loaders in context, not as global singletons, to avoid cross-user caching and authorization leaks.

Resolver composition: shared helpers, middleware, and directives

As schemas grow, repeating the same patterns across resolvers becomes error-prone. Resolver composition helps you keep mapping consistent. Common examples include: a wrapper that enforces authentication, a wrapper that checks roles for a specific field, a wrapper that records timing metrics, and a wrapper that normalizes errors. You can implement these as higher-order resolver functions or as server middleware/plugins depending on your GraphQL server.

For example, you might create a requireRole wrapper used by sensitive fields. The wrapper should be small and should not contain business logic; it should only enforce access and then delegate to the underlying resolver. Business rules still belong in services.

const requireRole = (role, resolver) => async (parent, args, ctx, info) => { if (!ctx.user || !ctx.user.roles.includes(role)) { throw new ForbiddenError(`Missing role: ${role}`); } return resolver(parent, args, ctx, info); }; export const resolvers = { Product: { internalCost: requireRole('ADMIN', (p) => p.internalCostCents) } };This keeps field-level mapping readable while ensuring consistent enforcement. If you later move role checks into schema directives, the same conceptual architecture applies: keep resolvers thin and policies centralized.

Mapping to multiple backends: orchestration vs delegation

Many GraphQL APIs sit in front of multiple systems: a primary database, a search service, and one or more internal microservices. Resolver architecture must decide when to orchestrate in GraphQL (combine results from multiple sources) and when to delegate to a backend that already provides an aggregate. Orchestration is flexible but can increase latency if it requires multiple network calls; delegation can be faster but may reduce GraphQL’s ability to tailor responses.

A practical strategy is: delegate for coarse-grained aggregates that are naturally owned by a service, and orchestrate for UI-driven compositions that cut across domains. For example, “Order with payment status and shipment tracking” might be delegated to an order service that already knows how to assemble it. But “Homepage feed” might orchestrate products, recommendations, and promotions from different systems, using batching and caching to keep it efficient.

Handling derived fields and expensive computations

Derived fields can be computed in resolvers, but you should be explicit about cost. Cheap derivations (formatting, simple arithmetic, mapping enums) are fine in field resolvers. Expensive derivations (full-text scoring, complex pricing rules, large aggregations) should be moved into services that can cache results, reuse computations, or push work down to the database/search engine.

If a derived field depends on other fields that might not be selected, avoid doing the work in the parent resolver. Instead, compute lazily in the field resolver so it only runs when requested. If it is requested frequently across many parents, consider precomputing at the list level or caching in a loader keyed by the inputs.

Dealing with pagination and list fields in resolver mapping

List fields are where mapping decisions have the biggest performance impact. A list resolver should return stable identifiers and enough metadata to support pagination. If you use cursor-based pagination, the resolver should translate GraphQL pagination args into backend queries (for example, “after cursor” into “WHERE id > lastId ORDER BY id LIMIT n”). The important architectural point is that pagination logic belongs in a service/repository method, not scattered across resolvers, so that multiple entry points can reuse it consistently.

For nested lists (for example, Customer.orders), avoid querying per parent. Use a loader that batches by parent IDs and supports pagination carefully. If each parent can request different pagination args, batching becomes harder. In that case, consider restricting nested pagination patterns (for example, fixed first N) or designing a separate entry point query for paginated lists. Another approach is to batch by a composite key (parentId + pagination window), but that reduces batching effectiveness.

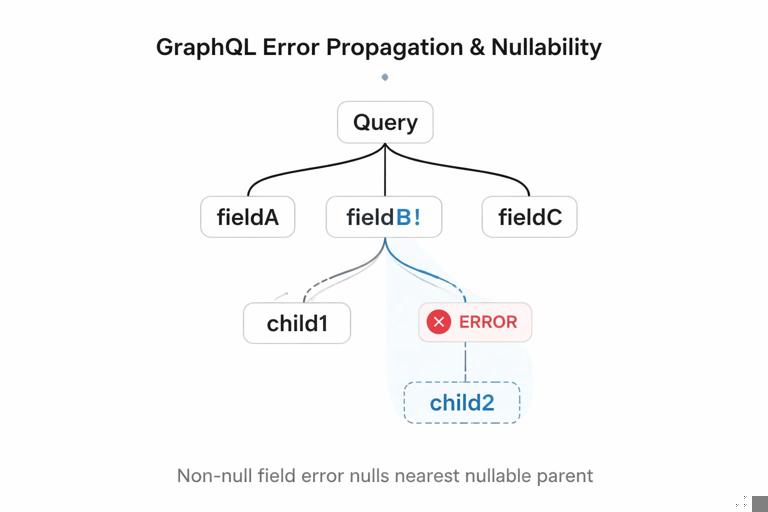

Error handling and nullability: mapping failures to schema behavior

Resolvers must translate backend failures into GraphQL’s error and nullability model. If a field is nullable, a resolver can return null when a downstream system fails, optionally adding an error. If a field is non-nullable and the resolver throws, GraphQL will null out the nearest nullable parent, potentially removing large parts of the response. Architecturally, this means you should be deliberate about where you throw errors versus returning null, and you should align this with user experience and reliability goals.

A practical pattern is to treat “not found” differently from “system failure.” For example, if inventory is temporarily unavailable, you might return null for inventory and include an error, allowing the rest of the product to render. If a user requests a product by ID and it does not exist, you might return null for the product query result (or throw a typed error) depending on your API contract. Implement this translation in services where possible, so resolvers remain consistent and thin.

Step-by-step: designing resolvers for a new feature

Step 1: List the fields and annotate data sources

Write down the object types involved and annotate each field with its source: database table/document, internal service, third-party API, or derived. Identify keys needed for joins (ids, foreign keys, skus). This prevents later refetching and clarifies what must be included in parent objects.

Step 2: Define service methods that match use cases

Create domain service methods that reflect the operations clients need, not the GraphQL shape. For example, define ProductService.listProducts and ProductService.getProductById. If you need to support filtering and sorting, put those options into service inputs. Ensure services can return resolver models containing required keys for nested fields.

Step 3: Implement repositories/clients with batch-friendly APIs

For each data source, implement methods that can fetch by many keys at once. For SQL, this might be WHERE id IN (...). For REST, prefer endpoints that accept multiple IDs or implement a gateway endpoint. For third-party APIs that do not support batching, consider caching and rate limiting, and be careful about exposing that field in high-cardinality lists.

Step 4: Add request-scoped loaders for repeated lookups

Create DataLoaders for common relationships: byId, byForeignKey, bySku. Place them in context so every resolver can use them. Ensure the batch function returns results in key order and handles missing values. Add per-request caching by default; add TTL caching only at a different layer (for example, Redis) if you need cross-request caching.

Step 5: Write resolvers as coordinators

Implement query resolvers that call services. Implement field resolvers only when needed: when the field is not a simple property, when it requires I/O, or when it needs authorization. Prefer returning parent objects that already include stored fields so default resolvers can handle them without extra code.

Step 6: Validate performance with representative queries

Run a few representative queries that include nested selections and lists. Count backend calls: database queries, remote HTTP calls, cache hits. If you see per-item calls, introduce batching or move fetching up a level. If you see overfetching, reduce the root fetch or split the service method. This step is part of mapping: you are aligning schema flexibility with predictable backend behavior.