Why database integration is different for GraphQL workloads

GraphQL changes how your backend hits the database because clients can ask for many shapes of data through a single endpoint. Instead of a fixed set of REST endpoints with predictable SQL, GraphQL produces highly variable query plans: one request might fetch a single object, another might traverse multiple relationships, and another might request deep nested lists with filters. This variability affects how you model data, how you batch and cache reads, how you paginate, and how you protect the database from expensive query patterns.

A practical way to think about database integration for GraphQL is: your schema defines a graph, but your database stores data in tables, documents, or key-value records. The job of your data layer is to translate graph-shaped requests into efficient database operations while preserving correctness (authorization, consistency) and performance (bounded query cost, minimal round trips).

Choosing a persistence model: relational, document, and hybrid

Relational databases (PostgreSQL, MySQL)

Relational databases are a strong default for GraphQL because relationships are explicit and joins are powerful. GraphQL queries often traverse relationships (user → posts → comments), which maps naturally to foreign keys and join tables. The main challenge is avoiding N+1 queries and controlling join explosion when clients request deep nested data.

Document databases (MongoDB)

Document stores can be efficient when the access pattern matches the document shape (for example, fetching a product with embedded variants). GraphQL, however, encourages flexible selection sets, so you must decide which fields to embed versus reference. Over-embedding can cause large documents and expensive updates; over-referencing can cause many round trips if not batched.

Hybrid approaches

Many production GraphQL backends use a hybrid approach: relational for core entities and transactions, plus a search index (Elasticsearch/OpenSearch) for full-text and faceted search, plus a cache (Redis) for hot reads. The key is to keep one source of truth for each piece of data and treat derived stores as projections that can be rebuilt.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Modeling data for GraphQL: access patterns first

Database modeling for GraphQL is most effective when driven by access patterns rather than mirroring the schema one-to-one. A GraphQL type is an API contract; it does not have to correspond to a single table or collection. Instead, design storage around: (1) the most common query paths, (2) the most expensive joins, (3) write consistency needs, and (4) pagination and filtering requirements.

Identify “root” entities and traversal hotspots

Start by listing the entities that are frequently queried as entry points: User, Organization, Product, Order, Article, etc. Then list the common traversals: Organization → members, Product → reviews, Order → lineItems → product. These hotspots are where you will invest in indexes, batching, and sometimes denormalized read models.

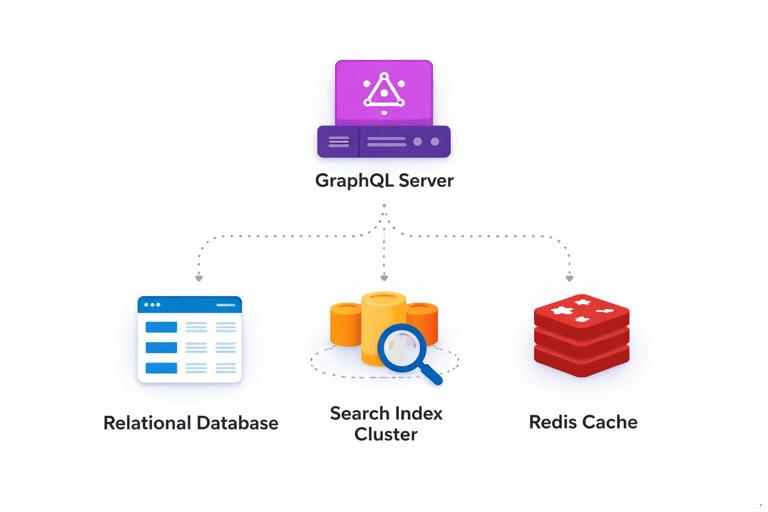

Separate read models from write models when needed

GraphQL clients often want rich read views (aggregations, counts, computed fields). If you force every read to be computed from normalized tables on the fly, you may overload the database. A common pattern is to keep a normalized write model (transactional tables) and add read-optimized projections (materialized views, summary tables, or cached aggregates) for common GraphQL fields like totalCount, ratingAverage, or lastActivityAt.

Relational modeling patterns that map well to GraphQL

One-to-many and many-to-many relationships

One-to-many maps cleanly to a foreign key (posts.user_id). Many-to-many typically uses a join table (organization_members with organization_id and user_id). In GraphQL workloads, many-to-many edges are frequently paginated and filtered, so design join tables with composite indexes that support the expected sort and filter patterns.

Example: if you frequently query organization members ordered by joinedAt, store joined_at on the join table and index (organization_id, joined_at, user_id) to support stable pagination.

Polymorphic relationships

Sometimes a table references multiple entity types (for example, Activity referencing either a Post or a Comment). In relational databases, polymorphic foreign keys are not enforced by constraints. For GraphQL workloads, prefer explicit join tables or separate nullable foreign keys when you need integrity and efficient joins. If you must use polymorphism, add a type discriminator and index it, and validate referential integrity at the application layer.

Soft deletes and visibility

GraphQL clients may request nested data that includes deleted or hidden records unless you enforce visibility consistently. If you use soft deletes (deleted_at), ensure every query path applies the same predicate. A practical approach is to centralize “visibility scopes” in your data access layer so resolvers cannot forget them.

Document modeling patterns for GraphQL

Embed for locality, reference for fan-out

Embedding works well when nested data is small, changes together, and is usually fetched with the parent. Referencing works better when nested lists can grow large (comments), when items are shared across parents, or when you need independent lifecycle and permissions.

For GraphQL, be careful embedding large arrays that clients might paginate. Pagination over embedded arrays can be expensive because the database may need to load the whole document. If you need cursor pagination on a list, referencing (separate collection) is often a better fit.

Precomputed fields in documents

Document stores make it easy to store computed fields (like commentCount) alongside the entity. This can speed up GraphQL fields that are frequently requested. The trade-off is maintaining correctness on writes; use atomic updates and background reconciliation jobs for safety.

Step-by-step: designing a GraphQL-friendly relational schema for a nested query

Consider a common GraphQL query shape in an e-commerce domain: fetch a product, its variants, and the first page of reviews with author info and a total count. The database should support: (1) fetching product by id or slug, (2) fetching variants by product_id, (3) fetching reviews by product_id with ordering, (4) fetching users by id in batch, and (5) computing totalCount efficiently.

Step 1: define tables and keys

-- products: stable identifier and a human-friendly slug for lookup by URL path

CREATE TABLE products (

id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

slug TEXT UNIQUE NOT NULL,

title TEXT NOT NULL,

description TEXT,

created_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT now()

);

-- variants: one-to-many

CREATE TABLE product_variants (

id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

product_id BIGINT NOT NULL REFERENCES products(id),

sku TEXT UNIQUE NOT NULL,

price_cents INTEGER NOT NULL,

created_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT now()

);

-- reviews: potentially large list, needs pagination and ordering

CREATE TABLE product_reviews (

id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

product_id BIGINT NOT NULL REFERENCES products(id),

author_user_id BIGINT NOT NULL,

rating SMALLINT NOT NULL,

body TEXT,

created_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT now()

);

-- users: referenced by reviews

CREATE TABLE users (

id BIGSERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

display_name TEXT NOT NULL,

avatar_url TEXT

);Step 2: add indexes for GraphQL access patterns

GraphQL list fields are commonly paginated and sorted. For reviews, you might paginate by created_at descending, with a tie-breaker by id for stable ordering. Add a composite index that matches the WHERE and ORDER BY.

CREATE INDEX idx_variants_product_id ON product_variants(product_id);

-- Supports: WHERE product_id = ? ORDER BY created_at DESC, id DESC

CREATE INDEX idx_reviews_product_created_id

ON product_reviews(product_id, created_at DESC, id DESC);

-- Users fetched by id in batch: primary key already indexedStep 3: plan for totalCount

Computing totalCount by running COUNT(*) for every request can be expensive at scale. Options include: (1) accept COUNT(*) with proper indexes for moderate scale, (2) maintain a counter on products (reviews_count), (3) maintain a separate summary table keyed by product_id, or (4) cache counts with a short TTL. Choose based on write volume and correctness needs.

ALTER TABLE products ADD COLUMN reviews_count INTEGER NOT NULL DEFAULT 0;Then update reviews_count transactionally when inserting/deleting reviews (or via triggers if you accept that trade-off).

Batching and minimizing round trips

GraphQL nested selection sets can cause N+1 query patterns: for each parent row, you query children separately. The fix is to batch by keys and fetch children in one query per field per request. This is a database integration concern because batching changes how you write SQL and how you structure your data access layer.

DataLoader-style batching for relational reads

A typical pattern is: collect all requested product_ids for variants, fetch all variants with WHERE product_id IN (...), then group results in memory. Do the same for users by author_user_id. The database benefits from fewer queries and better plan caching.

-- Fetch variants for many products at once

SELECT * FROM product_variants WHERE product_id = ANY($1::bigint[]);

-- Fetch users for many reviews at once

SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ANY($1::bigint[]);When batching, ensure you preserve ordering requirements. If the GraphQL field requires variants ordered by created_at, either order in SQL and then group, or group and sort per parent in memory. Prefer ordering in SQL when the dataset is large.

Batching for document databases

For MongoDB, batching often means using $in queries on referenced ids and projecting only requested fields. If you store references (review.authorUserId), you can fetch all authors in one query. If you embed authors, you avoid the join but pay in duplication and update complexity.

Pagination and filtering: designing indexes and query shapes

Cursor pagination in SQL

Offset pagination (LIMIT/OFFSET) becomes slow for large offsets and can produce inconsistent results when rows are inserted. Cursor pagination is more stable and typically faster. For GraphQL workloads, cursor pagination also helps bound database work because you can enforce a maximum page size.

Example: paginate reviews by (created_at, id) descending. The cursor encodes the last seen pair. The next page query uses a “seek” condition.

-- First page

SELECT *

FROM product_reviews

WHERE product_id = $1

ORDER BY created_at DESC, id DESC

LIMIT $2;

-- Next page (seek)

SELECT *

FROM product_reviews

WHERE product_id = $1

AND (created_at, id) < ($3::timestamptz, $4::bigint)

ORDER BY created_at DESC, id DESC

LIMIT $2;This pattern relies on the composite index matching the order. If you paginate by a different sort (rating, helpfulness), you may need additional indexes or restrict allowed sorts to a small set.

Filtering with selective indexes

GraphQL filters can be combinatorial (rating >= 4, createdAfter, hasBody). Avoid creating indexes for every combination. Instead, identify the most selective and common filters and index those. In PostgreSQL, partial indexes can be very effective for GraphQL fields that filter on boolean flags or soft deletes.

-- Only index visible reviews (if you have a visibility flag)

CREATE INDEX idx_reviews_visible_product_created

ON product_reviews(product_id, created_at DESC, id DESC)

WHERE body IS NOT NULL;Aggregations and computed fields without overloading the database

Counts, averages, and “top N”

GraphQL clients often request aggregates alongside lists: totalCount, averageRating, histogram buckets, or top reviewers. If you compute these with ad-hoc GROUP BY on every request, you may create heavy queries that compete with transactional traffic.

Practical options include: materialized views refreshed on a schedule, summary tables updated on writes, or asynchronous pipelines that update aggregates. Choose based on freshness requirements. For example, averageRating can be slightly stale, while inventory must be strongly consistent.

Materialized views (PostgreSQL example)

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW product_review_stats AS

SELECT

product_id,

COUNT(*) AS review_count,

AVG(rating)::float AS avg_rating

FROM product_reviews

GROUP BY product_id;

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX idx_review_stats_product_id

ON product_review_stats(product_id);You can refresh this view periodically or incrementally via a summary table. In GraphQL, fields like Product.reviewStats can read from this view quickly.

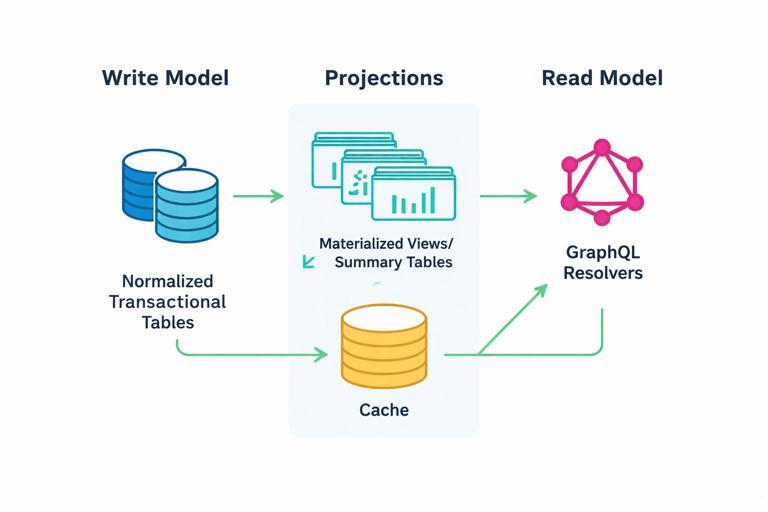

Transactions and consistency across GraphQL operations

GraphQL mutations often touch multiple tables: create an order, reserve inventory, create payment intent, write audit logs. Even if your schema exposes a single mutation field, the database work may be multi-step. Use database transactions to keep invariants intact, and design your data layer so that all writes for a mutation share the same transaction context.

Step-by-step: transactional write with derived counters

Example: create a review and update products.reviews_count. You want both operations to succeed or fail together.

BEGIN;

INSERT INTO product_reviews(product_id, author_user_id, rating, body)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3, $4);

UPDATE products

SET reviews_count = reviews_count + 1

WHERE id = $1;

COMMIT;If you also maintain avg_rating, you can store sum_rating and reviews_count to compute average without scanning all reviews. This is a common GraphQL optimization because averageRating is frequently requested.

Handling multi-source data: joining database data with external systems

GraphQL backends often combine database records with data from external services (billing provider, feature flags, recommendation engine). Database integration should minimize coupling: store stable identifiers (like billing_customer_id) and fetch external data only when requested. This keeps your database model clean and avoids storing volatile external payloads.

When an external field is frequently requested and slow to fetch, consider caching the external response keyed by the stable id, with an expiration policy. Keep the database as the source of truth for the identifier and relationship, not for the external system’s full state.

Protecting the database from expensive GraphQL queries

Enforce query complexity at the data layer

Even with good schema design, clients can request deep nesting and large lists. You should enforce maximum page sizes and restrict expensive sorts or filters. From a database perspective, the most important guardrails are: (1) hard limits on list sizes, (2) requiring pagination for large lists, (3) limiting depth for relationship traversal, and (4) timeouts and statement limits at the database driver level.

Use database timeouts and safe defaults

Set statement timeouts (PostgreSQL statement_timeout) or driver-level query timeouts to prevent runaway queries. Combine this with careful index design so normal queries complete well within the timeout.

Observability for database-backed GraphQL

To tune database integration, you need visibility into what GraphQL is doing to your database. Track per-request metrics: number of SQL queries, total DB time, slowest query, and rows returned. Correlate these with GraphQL operation names. This helps you find fields that cause N+1 patterns, missing indexes, or unexpectedly large result sets.

A practical workflow is: capture the top slow GraphQL operations, inspect the SQL generated during those operations, run EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS) on the slow queries, then add or adjust indexes, batching, or projections. Repeat until the operation is bounded and predictable.