What public-key cryptography is used for in real systems

Public-key cryptography gives you a key pair: a public key you can share widely and a private key you must protect. In practice, developers use it for three main jobs: (1) key agreement (establishing a shared symmetric key), (2) digital signatures (proving authenticity and integrity), and (3) encryption to a recipient’s public key (less common at scale than key agreement). Most modern protocols use public-key operations to bootstrap a session and then switch to symmetric cryptography for bulk data because it is faster and easier to use correctly.

When choosing algorithms and designing key management, separate “what security property do I need?” from “how do I store, rotate, and revoke keys?” A strong algorithm with weak key handling fails in production. This chapter focuses on practical choices (RSA vs ECC, signature vs key agreement) and the operational lifecycle of keys (generation, storage, rotation, revocation, and auditing).

Choosing between RSA and elliptic-curve cryptography (ECC)

RSA is widely supported and conceptually straightforward, but it requires larger keys and is slower than modern elliptic-curve options at comparable security levels. ECC (such as X25519 for key agreement and Ed25519 for signatures) provides strong security with smaller keys and faster operations, which helps performance and reduces bandwidth and storage overhead.

Recommended default choices in 2026

- Key agreement: X25519 (Curve25519 ECDH) for most new systems.

- Signatures: Ed25519 for most new systems.

- RSA: Use only when you need compatibility with legacy systems or specific ecosystems; prefer RSA-3072 or higher for new deployments.

These recommendations assume you are using well-maintained libraries and standard protocol constructions. Avoid designing your own hybrid schemes; use established protocols (TLS 1.3, SSH, age, JOSE with modern curves, etc.) and follow their algorithm constraints.

Security level mapping (rule of thumb)

- RSA-2048 roughly corresponds to ~112-bit security; acceptable for many cases but increasingly considered a minimum.

- RSA-3072 roughly corresponds to ~128-bit security; a common modern baseline.

- X25519 and Ed25519 target ~128-bit security with small keys.

Do not mix “key size” with “security level” across algorithm families. An ECC public key might be 32 bytes and still be comparable to RSA-3072 in security level.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Match the primitive to the job: key agreement, signatures, and encryption

Key agreement (ECDH) for sessions and envelopes

Key agreement lets two parties derive a shared secret without transmitting it. In practice, you use ECDH to derive symmetric keys for a session (like TLS) or to wrap a data-encryption key (DEK) for storage. X25519 is a strong default because it is designed to be hard to misuse and has widespread support.

Key agreement is not the same as authentication. ECDH alone can be vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks if you do not authenticate the peer’s public key. Authentication typically comes from certificates (PKI), pinned keys, or signatures.

Digital signatures for authenticity and non-repudiation-like properties

Signatures prove that a message was produced by someone holding the private key and that the message was not modified. Use signatures for software updates, API request signing, audit logs, and identity assertions. Ed25519 is a strong default: deterministic, fast, and with fewer foot-guns than many ECDSA implementations.

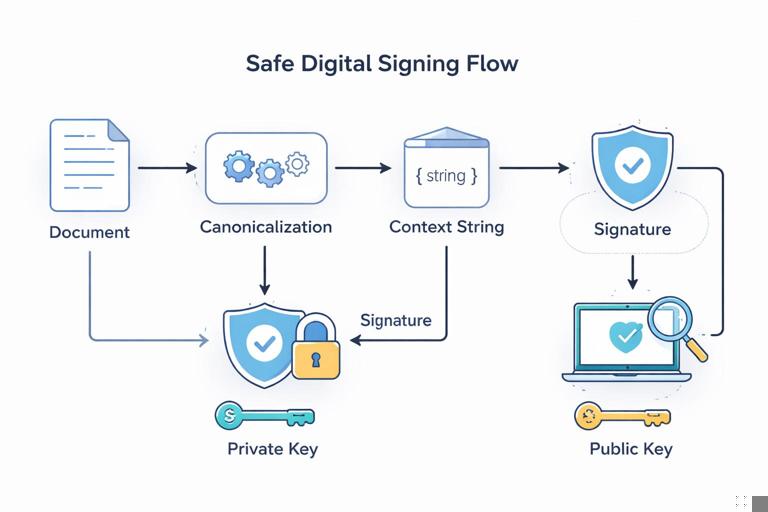

Be explicit about what is signed. Always sign a canonical representation (for example, a stable JSON canonicalization or a binary format) and include context strings to prevent cross-protocol attacks (e.g., signing the same bytes in two different contexts).

Public-key encryption (PKE) for specific cases

Direct public-key encryption (like RSA-OAEP) can be appropriate for encrypting small pieces of data (a symmetric key, a short token) to a known recipient. For larger data, use hybrid encryption: generate a random DEK, encrypt data symmetrically, then encrypt the DEK to the recipient using PKE or ECDH-based key wrapping. Many modern systems prefer ECDH-based hybrid encryption (HPKE) rather than raw RSA encryption.

Practical decision tree for developers

Use this decision tree to pick primitives without overthinking:

- Need to secure a network connection: use TLS 1.3; let it choose X25519 + Ed25519/ECDSA depending on certificates.

- Need to sign artifacts (binaries, containers, documents): use Ed25519 signatures; store public keys in a trusted distribution channel.

- Need to encrypt data for multiple recipients: use a hybrid scheme (e.g., HPKE or a well-reviewed envelope encryption design) with X25519 for recipient key wrapping.

- Need compatibility with old clients/HSMs: RSA-3072 for signatures and/or RSA-OAEP for key wrapping, but isolate legacy paths and plan migration.

When in doubt, choose a standard protocol rather than a primitive. Most real-world failures come from custom glue code, not from the math.

Key formats, encodings, and interoperability pitfalls

Keys are not just numbers; they are stored and transmitted in formats. Confusion between formats is a common source of bugs and security issues. Know what your library expects and what your system stores.

Common formats you will see

- PEM: Base64 with header/footer lines; often used for certificates and private keys.

- DER: Binary ASN.1 encoding; used under the hood for X.509 and many RSA/ECDSA keys.

- OpenSSH formats: SSH public keys and private keys have their own encodings.

- Raw keys: For X25519/Ed25519, many libraries use 32-byte raw keys; sometimes wrapped in a container for storage.

Interoperability rule: store keys in a format that preserves algorithm identifiers and parameters (or store those separately). If you store “just bytes,” you must also store metadata: algorithm, curve, usage (signing vs key agreement), creation time, and key ID.

Key identifiers (kids) and fingerprints

Systems often need a stable identifier for a key. A common approach is to compute a fingerprint of the public key (e.g., SHA-256 over a canonical encoding) and use it as a key ID. The key ID should not be treated as secret; it is an index. Ensure the fingerprint is computed over a canonical representation to avoid multiple encodings producing different IDs for the same key.

Key generation: where and how keys should be created

Key generation is an operational decision: generate keys on developer laptops only for testing; generate production keys in controlled environments. For production, prefer generating keys in an HSM, cloud KMS, or a dedicated signing service so private keys never appear on general-purpose machines.

Step-by-step: generating and registering an Ed25519 signing key (practical workflow)

This workflow is typical for signing software releases or configuration bundles.

- Step 1 — Generate the key pair in a protected environment: use an HSM/KMS if possible; otherwise use a locked-down build/signing host with restricted access.

- Step 2 — Export only the public key: the public key will be distributed to verifiers (clients, CI systems, update agents).

- Step 3 — Create a key record in your inventory: store key ID, algorithm (Ed25519), purpose (signing releases), owner/team, creation time, and rotation policy.

- Step 4 — Distribute the public key via a trusted channel: embed it in the application, ship it in a signed configuration, or publish it in a transparency/audited repository.

- Step 5 — Enforce usage separation: do not reuse the same key for signing releases and signing API requests; separate keys by purpose.

Even if you cannot use an HSM, you can still improve safety by limiting where the private key exists, using OS key stores, and requiring multi-party approval for signing operations.

Deterministic vs randomized signatures

Ed25519 signatures are deterministic, which avoids a class of failures where poor randomness leaks the private key (a known risk with some ECDSA deployments). This is one reason Ed25519 is often preferred for application-level signing.

Private key storage: practical options and trade-offs

Private keys are high-value secrets. Your storage choice should match the blast radius you can tolerate and the operational complexity you can manage.

Option 1: Hardware Security Modules (HSMs)

HSMs keep private keys inside tamper-resistant hardware and perform cryptographic operations without exposing key material. They support access control, auditing, and sometimes quorum policies. They are ideal for high-value signing keys (software updates, certificate authorities) and for long-lived service identity keys.

Option 2: Cloud KMS (managed key services)

Cloud KMS products provide HSM-backed or HSM-like protection with APIs. They are often the best default for cloud-native systems because they simplify rotation, IAM integration, and audit logging. The main trade-off is dependency on the cloud provider and careful IAM design to prevent misuse.

Option 3: OS key stores and secret managers

For smaller deployments, OS key stores (Windows DPAPI, macOS Keychain, Linux kernel keyrings) and secret managers can be acceptable. Ensure keys are encrypted at rest, access is limited to the service identity, and retrieval is audited. Avoid storing raw private keys in environment variables or configuration files.

Option 4: Application-managed encrypted key files (last resort)

If you must store a private key in a file, encrypt it with a key-encryption key (KEK) stored elsewhere (KMS/HSM). Do not rely on a passphrase typed by an operator for unattended services. Ensure file permissions are strict, and build a process for rotation and revocation.

Key usage separation and policy: prevent accidental cross-use

A common engineering mistake is using one key for multiple purposes because it “works.” This increases the impact of compromise and can create subtle protocol vulnerabilities. Enforce key usage separation with policy and code.

- Separate by purpose: signing vs key agreement vs encryption.

- Separate by environment: dev/staging/prod keys must never overlap.

- Separate by service: each service gets its own identity key pair.

- Separate by scope: different keys for different products or tenants when compromise boundaries matter.

In X.509 certificates, use KeyUsage and ExtendedKeyUsage constraints. In your own systems, store “allowed usages” in key metadata and enforce checks before performing operations.

Rotation: designing for change without outages

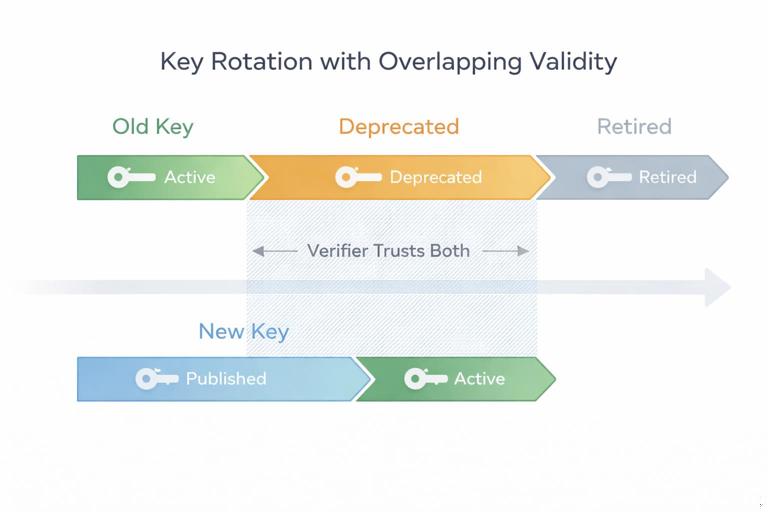

Rotation is not just “generate a new key.” It is a compatibility problem: verifiers must accept the new key while old signatures or sessions remain valid. Plan rotation from day one by supporting multiple active keys and by versioning.

Step-by-step: rotating a signing key with overlapping validity

- Step 1 — Generate a new key pair: assign a new key ID and record metadata.

- Step 2 — Publish the new public key: distribute it to all verifiers while still trusting the old key.

- Step 3 — Start signing with the new key: keep verifying with both old and new keys.

- Step 4 — Monitor adoption: measure how many clients have the new key (telemetry, version rollout, or access logs).

- Step 5 — Deprecate the old key: stop signing with it, but keep verifying for a defined grace period.

- Step 6 — Retire the old key: remove it from trust stores and mark it revoked in your inventory.

For API request signing, rotation often requires supporting multiple keys per client and including a key ID in requests so the server can select the right public key quickly.

Revocation and compromise response: what to do when a key leaks

Assume compromise will happen and design a response path. Revocation means different things depending on the system: removing a public key from a trust store, marking a certificate as revoked, disabling a KMS key version, or blocking a key ID at an API gateway.

Practical compromise playbook (developer-facing)

- Contain: disable the key in KMS/HSM or remove it from signing systems; rotate credentials that grant access to the key service.

- Replace: generate a new key pair and distribute the new public key.

- Invalidate: decide what previously signed/encrypted artifacts must be considered untrusted; for release signing, you may need to publish an advisory and force updates.

- Audit: review logs for key usage; identify suspicious signatures or decrypt operations.

- Prevent recurrence: tighten IAM, add approvals, move key to stronger storage, or reduce key scope.

Certificate revocation (CRLs/OCSP) exists in PKI, but many application-level systems do not have reliable online revocation checks. If you build your own trust distribution, prefer short-lived keys or short-lived certificates where feasible, and make trust stores updateable.

Public-key infrastructure (PKI) vs key pinning vs TOFU

How do you know a public key belongs to the right entity? There are three common approaches, each with operational implications.

PKI with certificates

Certificates bind a public key to an identity via a certificate authority (CA). This is the standard for TLS on the public internet and for many enterprise systems. The benefit is scalable trust: clients trust the CA set, not each individual server key. The cost is certificate lifecycle management: issuance, renewal, and handling mis-issuance or compromise.

Key pinning

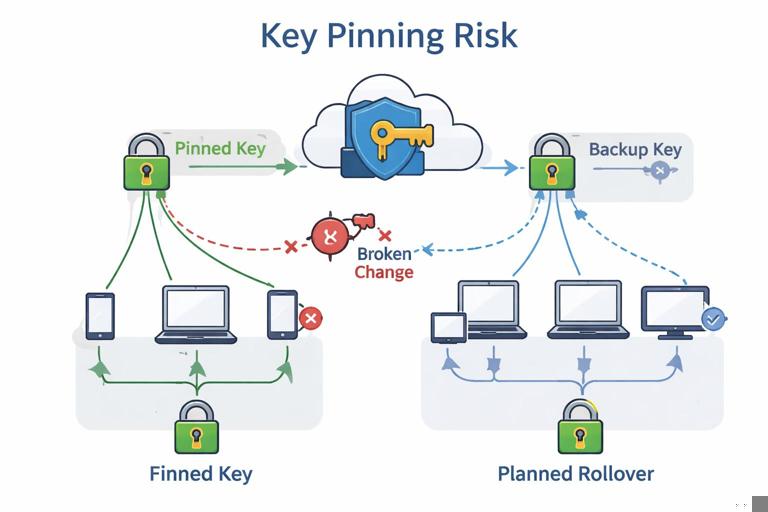

Pinning means the client trusts a specific public key (or a small set) for a service. This can be effective for internal services, embedded devices, or update systems. The risk is operational: if you lose the private key or need to rotate unexpectedly, pinned clients can brick themselves unless you planned an update path (pin sets, backup keys, or signed key rollovers).

TOFU (Trust On First Use)

TOFU is common in SSH: the first time you connect, you accept the server key and then expect it to remain stable. TOFU reduces dependency on CAs but requires good user experience and monitoring for key changes. It is best suited for admin tools and environments where first contact is controlled.

Envelope encryption and multi-recipient access control with public keys

A common pattern for data at rest is envelope encryption: data is encrypted with a DEK, and the DEK is protected separately. Public-key cryptography can be used to protect the DEK for one or more recipients.

Step-by-step: encrypting a file for multiple recipients using X25519-style wrapping

- Step 1 — Generate a random DEK: this key encrypts the file contents.

- Step 2 — Encrypt the file with the DEK: produce ciphertext and an authentication tag (details depend on your symmetric scheme, which is handled elsewhere in the course).

- Step 3 — For each recipient, derive a shared secret: use the sender’s ephemeral X25519 private key and the recipient’s X25519 public key.

- Step 4 — Derive a key-wrapping key: run a KDF over the shared secret plus context (recipient key ID, algorithm identifiers).

- Step 5 — Wrap the DEK for that recipient: store the wrapped DEK alongside the ciphertext with the recipient’s key ID.

- Step 6 — Decryption: recipient uses their private key to derive the same wrapping key and unwrap the DEK, then decrypts the file.

This design scales: adding a recipient means adding another wrapped DEK entry without re-encrypting the entire file. Use established standards like HPKE where possible to avoid subtle KDF and context-binding mistakes.

Operational inventory: treat keys like production assets

Key management becomes manageable when you maintain an inventory and enforce policy. At minimum, track: key ID, algorithm, purpose, owner, environment, creation date, rotation schedule, storage location (HSM/KMS/host), and current status (active, deprecated, revoked). Tie keys to services and deployments so you can answer: “Which systems depend on this key?” before rotating or revoking it.

Auditing and logging requirements

- Log key operations: sign, decrypt, unwrap, export attempts, policy changes.

- Alert on anomalies: spikes in signing, decrypt operations outside normal hours, usage from unexpected identities.

- Protect logs: logs are security data; restrict access and ensure integrity.

In many systems, the best improvement is not a new algorithm but better visibility: knowing when and where keys are used, and being able to shut down misuse quickly.

Common implementation mistakes to avoid

- Using raw RSA without OAEP/PSS: for RSA encryption use OAEP; for RSA signatures use PSS. Avoid legacy padding modes.

- Confusing signing and encryption keys: do not use the same key pair for both; enforce usage constraints.

- Not authenticating ECDH peers: unauthenticated key agreement is vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks.

- Storing private keys in source control or container images: treat this as an incident; rotate immediately.

- Hardcoding a single pinned key without a rollover plan: always support at least one backup/next key.

- Building custom serialization for signed data without canonicalization: signature verification failures and bypasses often come from ambiguous encodings.

- Ignoring algorithm agility: store algorithm identifiers and version fields so you can migrate later without breaking old data.

Minimal reference implementation patterns (pseudocode)

Pattern: signed API request with key ID

// Client constructs a canonical request string (method, path, timestamp, body hash, key_id) request = canonicalize(method, path, timestamp, body_hash, key_id) sig = Sign(private_signing_key, request) send headers: X-Key-Id: key_id, X-Timestamp: timestamp, X-Signature: base64(sig) // Server looks up public key by key_id, verifies timestamp window, verifies signaturePattern: verifying a signed artifact with a rotating key set

// Verifier has a trust store containing multiple public keys, each with status active/deprecated for key in trust_store: if Verify(key.public, artifact_bytes, signature): accept and record key_id used rejectThese patterns highlight two operational necessities: include a key identifier for efficient lookup, and support multiple keys during rotation.