Why Cursor-Based Pagination Exists

Problem with offset pagination: Offset-based pagination (limit/offset) looks simple but becomes unreliable and slow as datasets grow and change. If new rows are inserted or deleted between requests, users can see duplicates or miss items because “page 2” is no longer the same slice of data. Offsets also force the database to scan and discard rows to reach deep pages, which can be expensive.

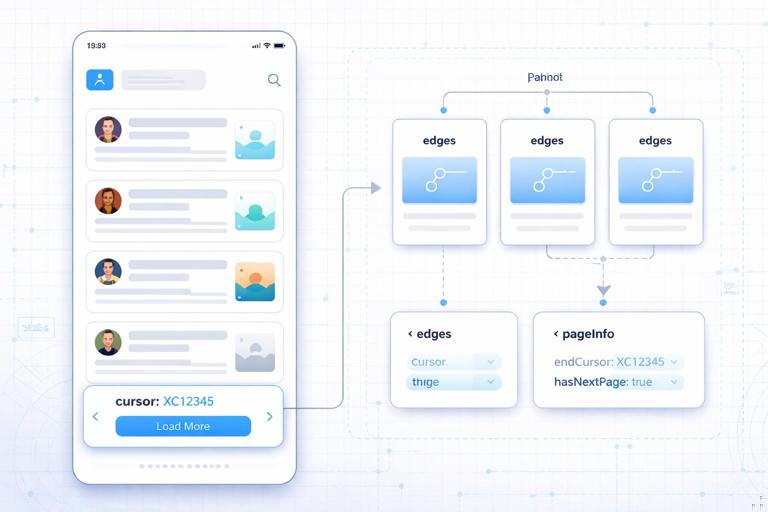

What cursor-based pagination solves: Cursor pagination anchors the next page to a specific item (a cursor) rather than a numeric offset. The client asks for “items after this cursor,” so inserts/deletes before that cursor do not reshuffle what comes next. This pattern is commonly expressed in GraphQL as a “connection” with edges, node, and pageInfo, enabling stable pagination and consistent UX for infinite scroll and feeds.

The Connection Model: Edges, Nodes, and PageInfo

Connection shape: A connection typically returns a list of edges, where each edge contains the node (the actual item) and a cursor (an opaque token). A pageInfo object provides navigation hints such as hasNextPage, hasPreviousPage, startCursor, and endCursor. This structure is designed to support forward and backward pagination without exposing internal database details.

type PageInfo { hasNextPage: Boolean! hasPreviousPage: Boolean! startCursor: String endCursor: String}type PostEdge { cursor: String! node: Post!}type PostConnection { edges: [PostEdge!]! pageInfo: PageInfo!}Arguments for navigation: The most common arguments are first and after for forward pagination, and last and before for backward pagination. You can also include ordering arguments, but you must ensure cursors remain meaningful under that ordering.

type Query { posts(first: Int, after: String, last: Int, before: String): PostConnection!}Designing a Cursor That Stays Stable

Opaque does not mean random: A cursor is “opaque” to clients, meaning clients should not parse it or rely on its internal structure. Internally, you still need it to encode enough information to resume the list deterministically. A good cursor is stable, unique for the chosen ordering, and efficient to decode.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

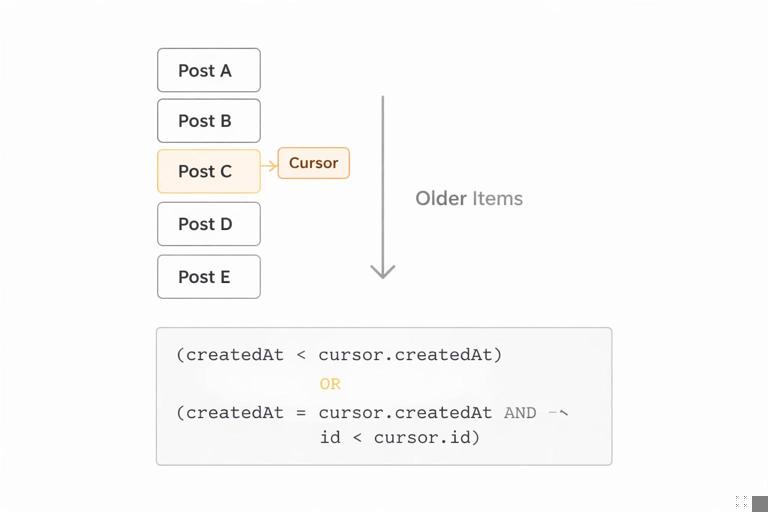

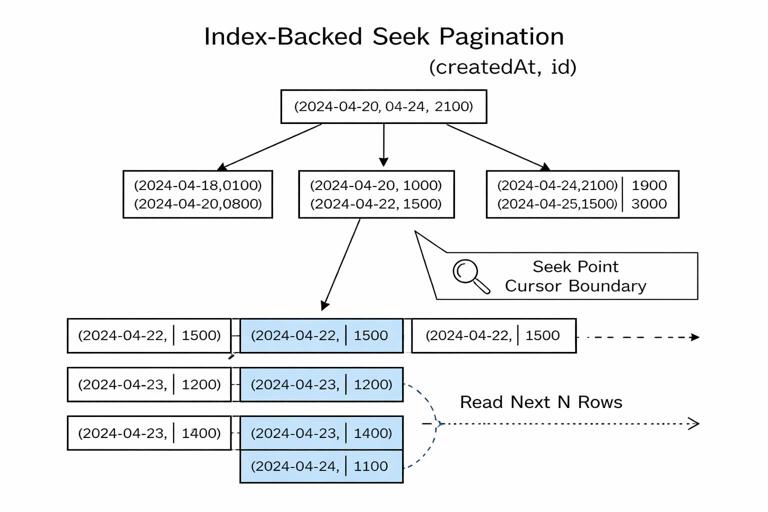

Choose a deterministic sort order: Cursor pagination depends on a strict ordering. If multiple items can share the same sort key (for example, createdAt), you must add a tie-breaker (often the primary key) to guarantee a total order. A typical ordering is (createdAt DESC, id DESC) for feeds.

Cursor payload patterns: Common cursor payloads include: (1) a single unique field like id when ordering by id; (2) a compound cursor like {createdAt, id} when ordering by time; (3) a database-native cursor token (less portable, but sometimes efficient). Encode the payload using base64 JSON to keep it opaque.

// Example internal cursor payload (before base64){ "createdAt": "2026-01-01T12:34:56.000Z", "id": "post_123" }Validate and version cursors: Cursors can become invalid if you change ordering rules. Add a small version field in the cursor payload (for example v:1) so you can reject or migrate old cursors safely.

Forward Pagination Step-by-Step (first/after)

Step 1: Define the ordering contract: Decide and document the default ordering for the connection. Example: posts are ordered by newest first using createdAt DESC, id DESC. The cursor must encode both createdAt and id to resume precisely.

Step 2: Decode the “after” cursor: If the client provides after, decode it to obtain the boundary values. If decoding fails, return a user-facing error (for example, “Invalid cursor”) rather than silently returning the first page, which can cause confusing duplicates.

Step 3: Build the boundary filter: For a descending order by (createdAt, id), “after cursor” means “items strictly older than the cursor item.” In SQL-like logic, that becomes: (createdAt < cursor.createdAt) OR (createdAt = cursor.createdAt AND id < cursor.id). This strict inequality prevents repeating the cursor item.

Step 4: Fetch one extra record: Request first + 1 items. If you got more than first, you know there is a next page. This avoids an extra count query and keeps latency predictable.

Step 5: Construct edges and pageInfo: For each returned row, create an edge with node and a cursor derived from that row. Set startCursor and endCursor from the first and last edge. Set hasNextPage based on whether you fetched the extra record. hasPreviousPage for forward-only queries can be computed if after is present, but be careful: “previous page exists” depends on whether there are items newer than the first returned item under the same filter; many APIs set it to Boolean(after) as a pragmatic hint, or compute it with a small extra query when needed.

// Pseudocode for forward paginationfunction listPosts({ first, after }) { const limit = clamp(first ?? 20, 1, 100); const cursor = after ? decodeCursor(after) : null; const where = cursor ? OR( LT("createdAt", cursor.createdAt), AND(EQ("createdAt", cursor.createdAt), LT("id", cursor.id)) ) : TRUE; const rows = db.posts.findMany({ where, orderBy: [{ createdAt: "desc" }, { id: "desc" }], take: limit + 1 }); const hasNextPage = rows.length > limit; const slice = hasNextPage ? rows.slice(0, limit) : rows; const edges = slice.map(r => ({ node: r, cursor: encodeCursor({ v: 1, createdAt: r.createdAt, id: r.id }) })); return { edges, pageInfo: { hasNextPage, hasPreviousPage: Boolean(after), startCursor: edges[0]?.cursor ?? null, endCursor: edges[edges.length - 1]?.cursor ?? null } };}Backward Pagination Step-by-Step (last/before)

Why backward pagination is trickier: When paginating backward, you often reverse the query direction to fetch efficiently, then reverse the results back to the client’s expected order. You must keep the ordering contract consistent: if the connection is “newest first,” the client expects that order regardless of whether they used first or last.

Step 1: Decode the “before” cursor: The before cursor represents an item boundary; “items before cursor” means “items strictly newer than the cursor item” when ordering newest-first. For (createdAt DESC, id DESC), the boundary filter becomes: (createdAt > cursor.createdAt) OR (createdAt = cursor.createdAt AND id > cursor.id).

Step 2: Query in the opposite direction: To get the “last N items” efficiently, you can query with ascending order and take last + 1, then reverse. Alternatively, some databases support “seek” queries with descending order and a bounded range, but the ascending-then-reverse approach is common and clear.

Step 3: Determine hasPreviousPage and hasNextPage: With backward pagination, hasPreviousPage indicates there are more items in the backward direction (older items, given newest-first ordering), while hasNextPage indicates there are newer items beyond the returned slice. Depending on your UI, you may compute both via the extra-record technique plus whether before was provided.

// Pseudocode for backward paginationfunction listPostsBackward({ last, before }) { const limit = clamp(last ?? 20, 1, 100); const cursor = before ? decodeCursor(before) : null; const where = cursor ? OR( GT("createdAt", cursor.createdAt), AND(EQ("createdAt", cursor.createdAt), GT("id", cursor.id)) ) : TRUE; // Query oldest-to-newest within the bounded set const rowsAsc = db.posts.findMany({ where, orderBy: [{ createdAt: "asc" }, { id: "asc" }], take: limit + 1 }); const hasExtra = rowsAsc.length > limit; const sliceAsc = hasExtra ? rowsAsc.slice(rowsAsc.length - limit) : rowsAsc; const slice = sliceAsc.reverse(); // back to newest-first const edges = slice.map(r => ({ node: r, cursor: encodeCursor({ v: 1, createdAt: r.createdAt, id: r.id }) })); return { edges, pageInfo: { hasPreviousPage: hasExtra, hasNextPage: Boolean(before), startCursor: edges[0]?.cursor ?? null, endCursor: edges[edges.length - 1]?.cursor ?? null } };}Handling Sorting and Filtering Without Breaking Cursors

Include filter context in the cursor? Usually no: A cursor should identify a position in a specific ordered list. If the client changes filters (for example, category) but reuses an old cursor, results can be surprising. Many APIs treat cursors as valid only for the same query shape and return an error if the cursor is incompatible. Another approach is to encode a hash of relevant filter/sort parameters in the cursor payload and reject mismatches.

OrderBy arguments must be constrained: Allowing arbitrary ordering can explode complexity and index requirements. Prefer a small set of supported orderings (for example, NEWEST, OLDEST, TOP) and define cursor payloads per ordering. If you support TOP based on a score that changes frequently, cursor pagination may become unstable; consider time-bucketed scores or a snapshot mechanism.

Stable ordering with mutable fields: If the sort key can change (like updatedAt), items can “move” between pages. Cursor pagination still works mechanically, but the user experience can be odd (items reappearing). For feeds, prefer immutable or monotonic keys like createdAt or an append-only sequence.

Edge Cases: Duplicates, Gaps, and Deletions

Deletions: If the item referenced by the cursor is deleted, the cursor can still be valid if it encodes the sort keys rather than requiring the row to exist. That is one reason compound cursors are useful: you can resume from the boundary values even if the exact row is gone.

Concurrent inserts: New items inserted “ahead” of the current cursor (newer items in a newest-first feed) will not affect the next page when using after; they will appear if the client refreshes from the top. This is typically desirable for feeds.

Duplicates due to non-unique sort keys: If you paginate by createdAt alone, multiple items with the same timestamp can cause duplicates or skips when using strict inequalities. Always include a unique tie-breaker in both ordering and cursor payload.

Performance Characteristics and Indexing Implications

Seek pagination is index-friendly: Cursor pagination is often called “seek pagination” because the database can seek directly to the boundary using an index, then read the next N rows. To get the benefit, you need an index matching your order and filter pattern. For example, for createdAt DESC, id DESC, an index on (createdAt, id) supports efficient range scans.

Avoid count(*) for pageInfo: Counting total rows for every connection request is expensive and often unnecessary. Prefer hasNextPage via the “fetch one extra” technique. If you must provide total counts, consider making it a separate field that clients request explicitly, and compute it with caching or approximate methods.

Batching and N+1: Connections often return nodes that include nested fields. Ensure your resolvers batch nested lookups so that fetching 20 nodes does not trigger 20 additional database calls. Cursor pagination reduces the number of nodes per request, but it does not automatically solve N+1 patterns.

API Ergonomics: Limits, Defaults, and Error Handling

Enforce maximum page size: Always clamp first and last to a server-defined maximum to protect performance. Return a clear error if the client requests too much, or silently clamp while exposing the applied limit in extensions or a debug field (depending on your API style).

Mutual exclusivity rules: Define how first/after interact with last/before. Many APIs disallow mixing first with last in the same request to avoid ambiguous intent. If you allow it, document the precedence and ensure consistent behavior.

Invalid cursor behavior: Treat cursors as untrusted input. Validate base64, validate JSON shape, validate types, validate version, and validate that the cursor fields make sense (for example, parseable timestamp). Return a typed GraphQL error with a stable error code so clients can recover.

Security Considerations for Cursor Tokens

Do not leak internal identifiers unintentionally: Even though base64 is not encryption, it can expose raw IDs or timestamps if clients decode it. If that is sensitive, sign and/or encrypt the cursor. A common approach is to base64-encode JSON and add an HMAC signature, or use an authenticated encryption scheme. The goal is to prevent tampering and reduce information leakage.

Prevent cursor tampering: If cursors are not signed, a client can modify them to jump around the dataset or probe for data boundaries. Even if authorization checks exist, tampering can increase load or reveal timing differences. Signing cursors lets you reject altered tokens early.

// Example cursor payload with signature (conceptual){ "v": 1, "createdAt": "...", "id": "...", "sig": "HMAC(...)" }Authorization still applies per node: A valid cursor should not grant access. Always apply authorization filters in the underlying query (for example, only posts visible to the viewer). If visibility depends on the viewer, the same cursor value might not be valid across users; signing cursors with a viewer-specific secret or embedding a viewer context hash can help prevent cross-user reuse.

Implementing Connections in Resolvers: A Practical Workflow

Step 1: Normalize arguments: Convert missing values to defaults, clamp limits, and enforce mutually exclusive combinations. Decide whether to support both directions in one resolver or split into two internal code paths.

Step 2: Decode cursor and build a “seek” condition: Convert the cursor into boundary values and produce a strict inequality condition that matches your ordering. Keep this logic centralized so every connection uses the same, tested behavior.

Step 3: Query with limit+1: Fetch one extra row to compute hasNextPage or hasPreviousPage. Avoid offset. Ensure the query uses the same ordering as your cursor encoding.

Step 4: Map rows to edges: For each row, compute the cursor from the row’s ordering fields. Do not reuse the incoming cursor; always generate cursors from returned nodes.

Step 5: Compute pageInfo consistently: Set startCursor and endCursor from edges. Compute hasNextPage/hasPreviousPage based on direction and the extra row. If you provide both forward and backward navigation, test combinations like: first page, middle page, last page, empty results, and single-item results.

Testing Pagination Correctness

Golden tests for ordering: Create a deterministic dataset with repeated timestamps and verify that paginating through all pages returns every item exactly once. This catches missing tie-breakers and incorrect inequality directions.

Mutation between page requests: Simulate inserts and deletes between requests. Verify that forward pagination does not produce duplicates and that deletions do not break cursor decoding. Ensure your cursor does not require the referenced row to exist.

Fuzz invalid cursors: Test random strings, truncated base64, wrong JSON types, and wrong versions. Confirm that errors are consistent and do not expose stack traces or internal details.