Why filtering and sorting need deliberate design

Filtering and sorting are where GraphQL’s flexibility can either empower clients or create unpredictable, expensive queries. Because clients can shape queries freely, a “just expose everything” approach often leads to inconsistent semantics (different fields filter differently), unstable ordering (results change between requests), and performance surprises (filters that force full scans or sorting on computed fields). A deliberate design makes queries predictable: clients know which filters exist, how they combine, how nulls behave, what ordering is stable, and what the API will reject.

In this chapter, “predictable” means: (1) the same input always yields the same logical result, (2) ordering is deterministic, (3) filter behavior is consistent across types, (4) the server can validate and cost-control queries, and (5) the design maps cleanly to underlying indexes and query plans. The goal is not maximum expressiveness; it is a contract that clients can rely on and that the server can execute efficiently.

Principles for predictable filter semantics

Principle 1: Make filter operators explicit

A common anti-pattern is to accept a free-form “where” object that mirrors database syntax or allows arbitrary operators. This makes it hard to document, validate, and evolve. Instead, define a small, explicit set of operators and apply them consistently. For example: eq, in, contains, startsWith, lt, lte, gt, gte, between, and a dedicated isNull for null checks. Avoid overloading eq: null to mean “is null” because it blurs intent and can behave differently across data sources.

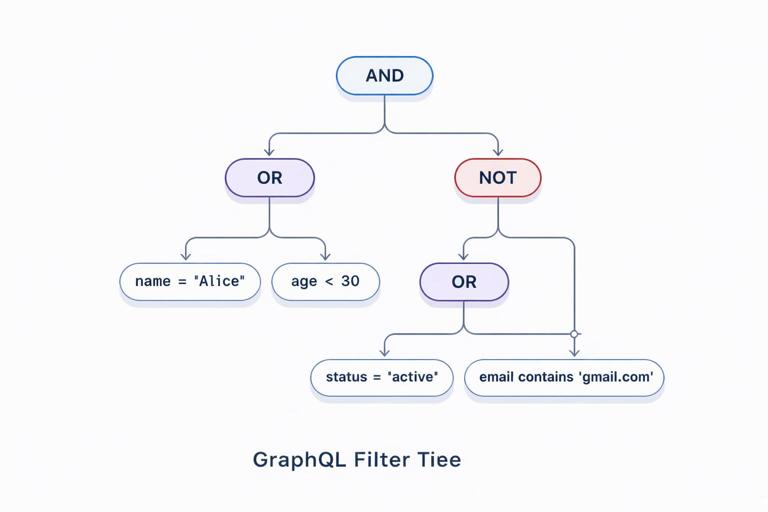

Principle 2: Define how filters combine (AND/OR/NOT)

Clients need to know whether multiple fields inside a filter input are combined with AND or OR. The most predictable default is AND at the same level, with explicit and, or, and not fields for grouping. This mirrors how people reason about constraints and keeps simple cases simple. It also avoids ambiguous behavior when clients provide multiple operators for the same field.

Principle 3: Separate filtering from searching

“Search” (full-text, fuzzy matching, relevance ranking) has different semantics and performance characteristics than structured filtering. Mixing them into the same input often leads to confusion: does contains mean substring, token match, or full-text? A predictable design separates them: structured filters for exact/relational constraints, and a dedicated search argument (or field) for full-text queries with clearly documented behavior and limits.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Principle 4: Make null handling explicit

Nulls are a frequent source of surprises. Decide and document: (1) whether null values are included when a field filter is absent (usually yes), (2) how eq behaves when the field is null (usually false unless comparing to null is allowed), and (3) how sorting places nulls (first/last). Provide explicit controls like nulls: FIRST|LAST in sort inputs and isNull in filters to avoid implicit behavior that differs between databases.

Principle 5: Prefer allowlists over arbitrary field filtering

Letting clients filter on any scalar field seems convenient, but it creates unstable performance and makes it hard to guarantee indexes. A predictable API uses allowlists: only expose filters for fields you can support efficiently and consistently. If you need broad flexibility, expose it gradually with clear deprecation and versioning strategies, and keep the operator set stable.

Designing filter input types

A reusable operator pattern

A practical approach is to define reusable “operator” input types per scalar category (string, number, date/time, boolean, ID). Then compose them into per-entity filter inputs. This keeps behavior consistent across the schema and reduces documentation burden.

input StringFilter { eq: String in: [String!] contains: String startsWith: String endsWith: String isNull: Boolean } input IntFilter { eq: Int in: [Int!] lt: Int lte: Int gt: Int gte: Int between: IntRange isNull: Boolean } input IntRange { min: Int! max: Int! } input DateTimeFilter { eq: DateTime in: [DateTime!] lt: DateTime lte: DateTime gt: DateTime gte: DateTime between: DateTimeRange isNull: Boolean } input DateTimeRange { from: DateTime! to: DateTime! }Note the explicit isNull. If you include it, define precedence rules when combined with other operators. A simple rule is: if isNull is provided, it must be the only operator for that field (server validates and rejects otherwise). This prevents contradictory inputs like { isNull: true, eq: "x" }.

Composing entity filters with logical groups

Now define an entity filter input that uses these operator types and includes logical composition fields. Keep the naming consistent across entities (e.g., always and, or, not), and ensure recursion depth is bounded by validation to prevent pathological queries.

input OrderFilter { id: IDFilter status: StringFilter customerId: IDFilter createdAt: DateTimeFilter totalCents: IntFilter and: [OrderFilter!] or: [OrderFilter!] not: OrderFilter }Decide whether and and or accept empty arrays. A predictable rule is to reject empty arrays (validation error) and treat missing fields as “no constraint.” This avoids edge cases where and: [] could be interpreted as always true.

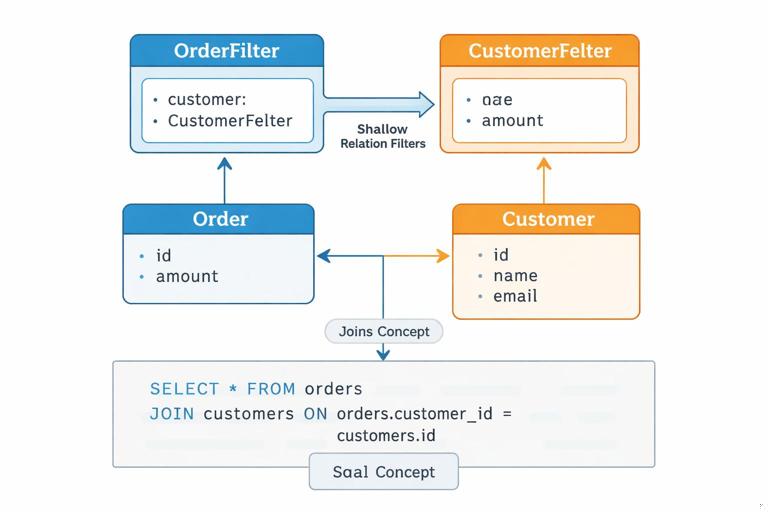

Filtering on relations: be selective

Filtering across relations (e.g., orders where customer has a certain email) is powerful but can explode query complexity. A predictable design exposes relation filters only where you can support them efficiently and where the semantics are clear. When you do expose them, name them explicitly and keep them shallow unless you have strong guardrails.

input CustomerFilter { id: IDFilter email: StringFilter } input OrderFilter { customer: CustomerFilter ... }Also define whether relation filters mean “exists” semantics. For example, filtering orders by customer: { email: { eq: "a@b.com" } } implies the order must have a customer and that customer must match. If orders can be guest checkouts, document that guest orders will not match relation filters unless you provide explicit guest fields.

Designing sort inputs for deterministic ordering

Always require a stable tie-breaker

Sorting must be deterministic, especially when combined with pagination (even if pagination patterns were covered earlier, stable ordering is still a sorting concern). If clients sort by a non-unique field like createdAt, ties are common. If the server does not define a tie-breaker, the order of tied rows can change between requests. A predictable design enforces a stable secondary sort, typically by a unique field like id.

You can enforce this in two ways: (1) server automatically appends id as a final sort key, or (2) require clients to include it. Option (1) is more ergonomic and still predictable if documented clearly.

Use an explicit list of sort keys

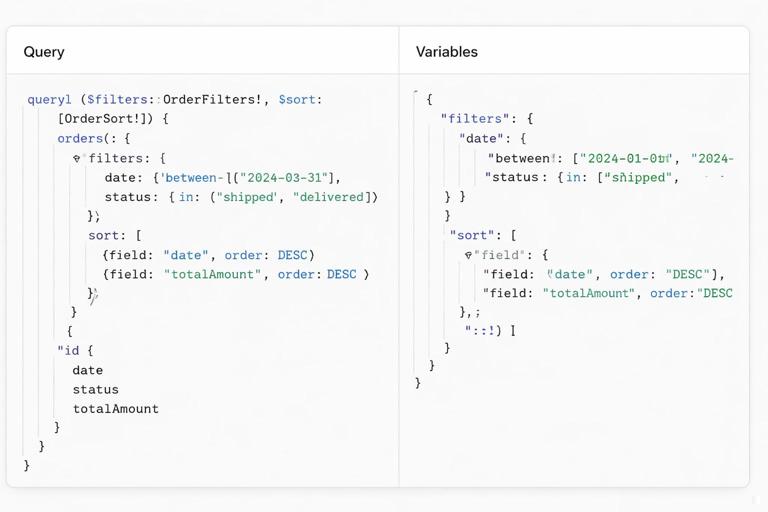

Instead of a single orderBy field, accept a list of sort clauses. This supports multi-column ordering and makes tie-breakers explicit. Keep the sort keys allowlisted and aligned with indexes.

enum SortDirection { ASC DESC } enum NullsPosition { FIRST LAST } enum OrderSortField { CREATED_AT TOTAL_CENTS STATUS ID } input OrderSort { field: OrderSortField! direction: SortDirection! nulls: NullsPosition } Then in your query:

type Query { orders(filter: OrderFilter, sort: [OrderSort!]): [Order!]! }Define defaults. A predictable default might be sort: [{field: CREATED_AT, direction: DESC}, {field: ID, direction: ASC}]. Document that if sort is omitted, this default applies.

Avoid sorting on computed or nested fields unless you can guarantee performance

Sorting by computed fields (e.g., “number of items in order”) or nested fields (e.g., customer email) can require joins, aggregations, or post-processing. If you expose such sorts, do so intentionally: name them clearly (e.g., ITEM_COUNT), document their cost, and consider restricting them behind feature flags or stricter limits. Predictability includes predictable latency; if a sort can degrade dramatically with data size, it should not be casually available.

Step-by-step: define a predictable filter and sort contract

Step 1: List client use cases and classify them

Start with concrete client questions, not database capabilities. For an orders list, typical use cases might be: “orders in a date range,” “orders by status,” “orders for a customer,” “high-value orders,” and “orders containing a SKU.” Classify each as structured filter, relation filter, or search. If “containing a SKU” requires joining line items, decide whether it’s a supported structured filter or a separate query endpoint/field.

Step 2: Choose operator sets per field type

For each scalar category, decide the allowed operators. For strings, you might allow eq, in, contains, startsWith, and isNull. For IDs, typically only eq and in. For numeric totals, allow comparisons and ranges. Keep the set small; every operator multiplies test cases and documentation.

Step 3: Decide combination logic and validation rules

Define: (1) same-level fields are ANDed, (2) or is an array of subfilters, (3) not negates a subfilter, (4) recursion depth limit (e.g., max depth 5), and (5) maximum number of nodes in the filter tree (e.g., 100). These constraints prevent clients from sending enormous boolean expressions that are expensive to translate and execute.

Step 4: Define sorting defaults and tie-breakers

Pick a default sort that matches the most common UI. Ensure it is stable by appending a unique tie-breaker. Decide null ordering defaults and whether clients can override them. If your underlying database has different null ordering than your API contract, normalize it in the query builder so the API stays consistent across environments.

Step 5: Document examples as part of the contract

Predictability improves when clients can copy known-good patterns. Provide examples for common cases and edge cases: null checks, OR groups, and multi-sort. Keep examples aligned with your validation rules.

# Orders created in a range AND status in a set query Orders($filter: OrderFilter, $sort: [OrderSort!]) { orders(filter: $filter, sort: $sort) { id status createdAt totalCents } } # Variables { "filter": { "createdAt": { "between": { "from": "2026-01-01T00:00:00Z", "to": "2026-01-31T23:59:59Z" } }, "status": { "in": ["PAID", "SHIPPED"] } }, "sort": [ { "field": "CREATED_AT", "direction": "DESC" }, { "field": "ID", "direction": "ASC" } ] }Resolver-side execution: translating filters and sorts safely

Build an intermediate representation (IR) before hitting the database

To keep behavior consistent across data sources, translate GraphQL filter inputs into an intermediate representation: a small AST describing comparisons and boolean groups. Validate the IR (operator compatibility, depth, node count, field allowlist) before generating SQL/ORM queries. This avoids “leaking” database-specific behavior into your API and makes it easier to unit test filter semantics without a database.

For example, a filter like { or: [ { status: { eq: "PAID" } }, { totalCents: { gt: 10000 } } ] } becomes an IR node OR with two children, each a comparison. The same IR can be compiled to SQL, to a search engine query, or to an in-memory filter for tests.

Validate operator-field compatibility

Even with typed inputs, you still need semantic validation. For instance, you might allow contains only on specific fields (like email) and disallow it on others (like status) even though both are strings. Similarly, you might disallow in lists longer than a threshold to avoid huge parameter lists. Return clear errors that tell clients what to change.

Normalize sorting and enforce allowlists

Translate the sort list into a normalized internal form. Apply defaults when missing, append tie-breakers, and reject unsupported fields. Also enforce a maximum number of sort clauses (e.g., 3) to keep query plans stable. If you support sorting on relations, ensure you can generate deterministic SQL (including join conditions) and that the join does not multiply rows unexpectedly.

Performance guardrails that preserve predictability

Limit filter complexity and input size

Predictable performance requires rejecting or constraining expensive shapes. Common guardrails include: maximum depth of nested and/or/not, maximum number of OR branches, maximum length of in arrays, and maximum range window for date filters (e.g., no more than 2 years) if your dataset is huge. These limits should be documented as part of the API contract so clients can design around them.

Align filters and sorts with indexes

When you expose a filter or sort, you are implicitly promising it will work at scale. Ensure each allowlisted field has an index strategy. For example, if you allow sorting by createdAt, you likely need an index on (createdAt, id) to support stable ordering efficiently. If you allow filtering by status and sorting by createdAt, consider composite indexes that match common combinations. If you cannot index a field (e.g., a large text blob), don’t expose it as a filter/sort, or expose it only through a dedicated search system.

Be careful with case-insensitive matching

Clients often want case-insensitive filters for strings. Decide whether eq is case-sensitive or not, and keep it consistent. If you support case-insensitive matching, define it explicitly (e.g., eqInsensitive or a mode field like mode: INSENSITIVE). Hidden case-folding rules vary by database collation and locale, which can break predictability. If you must support it, normalize values (e.g., store a lowercased column) and document the normalization rules.

Common design pitfalls and how to avoid them

Pitfall: “Generic JSON filter” inputs

Accepting a JSON blob for filters seems flexible but sacrifices type safety, introspection, and tooling. It also makes it easy for clients to send unsupported operators. Prefer typed inputs with explicit operators so the schema communicates the contract and clients get validation before runtime.

Pitfall: Ambiguous “sortBy” strings

Using sortBy: "createdAt_DESC" or similar string encodings is compact but brittle and hard to evolve. Prefer structured inputs with enums for fields and direction. This also prevents clients from attempting to sort by fields you cannot support.

Pitfall: Inconsistent semantics across lists

If one list uses filter with AND semantics and another uses OR semantics, clients will make mistakes. Standardize naming and behavior across your schema: the same operator names, same null rules, same combination logic, and similar defaults. If a specific list must differ (for performance or domain reasons), make that difference explicit in naming (e.g., ordersSearch vs orders) rather than silently changing semantics.

Pitfall: Exposing filters that depend on authorization context without clarity

Sometimes the set of visible records depends on the viewer (e.g., only orders in the viewer’s organization). If you also allow filtering by organizationId, clients may get confusing results (filter says org A, auth restricts to org B, result empty). A predictable design either omits such filters and derives them from context, or clearly documents that authorization constraints are always applied in addition to client filters. In resolver logic, apply authorization constraints as mandatory filters that cannot be overridden.