Why operational templates matter (and what makes them different from “a spreadsheet”)

In operations, the cost of variation is rework: someone enters the same information twice, interprets a field differently, forgets a step, or formats data in a way that breaks downstream reporting. Operational templates are purpose-built Excel workbooks (or sets of workbooks) that standardize how work is captured, processed, and handed off. They reduce rework by making the “right way” the easiest way, and by producing outputs that are consistent enough to be automated.

An operational template is not just a blank sheet with headers. It is a repeatable workflow packaged into a file: it defines what inputs are needed, how they are collected, how they are transformed, what outputs are produced, and how exceptions are surfaced. The template becomes a contract between the person doing the work and the next step in the process (a dashboard, a supervisor review, an ERP upload, a customer email, a weekly KPI pack).

In this chapter, you will build and refine templates that standardize operational work while staying flexible enough for real-world variability. The focus is on: (1) designing templates around process steps, (2) using Power Query to enforce structure and automate preparation, (3) embedding checklists and handoff rules, and (4) making templates resilient to common operational changes (new sites, new SKUs, new reason codes).

Template types that reduce rework in operations

1) Capture templates (front-line data entry)

Capture templates are used at the point of work: receiving logs, cycle counts, maintenance checklists, incident reports, daily production tallies. Their job is to make data entry fast and consistent, and to minimize interpretation differences between users.

- Typical outputs: a clean table that can be appended to a master dataset, plus an exception list for missing/invalid items.

- Rework reduced: fewer clarifying messages, fewer “what does this mean?” follow-ups, fewer manual cleanup steps.

2) Processing templates (standard transformations and calculations)

Processing templates take raw extracts (CSV exports, system reports, emailed files) and convert them into standardized datasets for dashboards and trackers. Their job is to remove manual “prep work” such as splitting columns, fixing dates, normalizing codes, and merging reference data.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

- Typical outputs: standardized fact tables, dimension tables, and a refreshable model-ready dataset.

- Rework reduced: fewer repeated cleanup steps each week, fewer mistakes from copy/paste transformations.

3) Handoff templates (packaging outputs for the next step)

Handoff templates produce outputs that are ready to send or upload: a weekly KPI pack, a customer SLA report, a purchase order request list, a replenishment recommendation file. Their job is to ensure the output always matches an agreed format and includes required fields.

- Typical outputs: a formatted export range, a CSV-ready table, or a PDF-ready report layout.

- Rework reduced: fewer rejected uploads, fewer “please resend in the correct format” requests.

Design principle: build templates around the process, not around the sheet

A reliable operational template maps to a workflow. Before you build, write down the process in 6–10 steps. Example for a daily receiving log:

- Collect deliveries and paperwork

- Record supplier, PO, arrival time

- Record SKU, quantity, condition

- Flag discrepancies (short, over, damaged)

- Assign disposition and owner

- Submit log to supervisor

- Append to master receiving history

Now translate that into a workbook structure that mirrors the flow:

- Input sheet: the capture table and minimal instructions

- Reference sheet(s): lists like suppliers, SKUs, reason codes, shift schedule

- Review sheet: exceptions and completeness checks

- Output sheet: standardized export table or refreshable query output

- Admin sheet (optional): parameters like site code, reporting period, file paths

This structure reduces rework because users know where to go for each step, and because the template can enforce a consistent handoff.

Step-by-step: build a capture template that appends cleanly to a master dataset

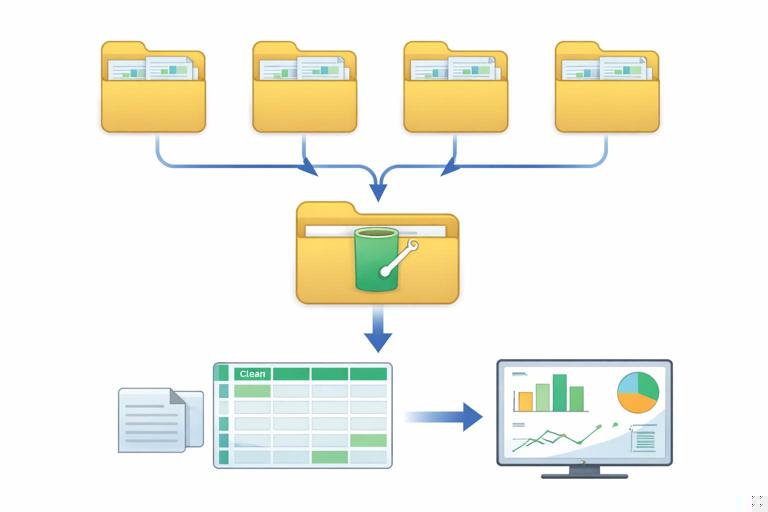

The goal: a daily log file that multiple sites can use, where each file can be dropped into a folder and automatically appended into a master dataset using Power Query.

Step 1: define the canonical schema (the “contract”)

Create a list of required columns and their meaning. Keep names stable and unambiguous. Example schema for a receiving log:

- Site

- LogDate

- Shift

- Supplier

- PONumber

- SKU

- QtyReceived

- UOM

- Condition

- DiscrepancyType

- DiscrepancyQty

- Owner

- Notes

Decide which are required vs optional. Decide data types (date, whole number, text). Decide allowed values for categorical fields (Shift, UOM, Condition, DiscrepancyType). This schema is the foundation that prevents downstream rework.

Step 2: create a single input table with stable column names

On the Input sheet, create an Excel Table with exactly the schema columns. Name the table something stable like tblReceivingLog. Keep the table as the only place users type operational data.

Practical guidance:

- Put short instructions above the table (not inside it) so they don’t become part of the dataset.

- Freeze the header row for usability.

- Keep formatting minimal; focus on clarity and speed.

Step 3: add a template ID and version metadata (for governance)

Rework often happens when different teams use “almost the same” template. Add a small Admin area (or Admin sheet) with:

- TemplateName (e.g., ReceivingLog)

- TemplateVersion (e.g., 1.3)

- SiteCode (default for the file)

- PreparedBy (optional)

In the input table, populate the Site column from SiteCode so users don’t type it repeatedly. This also ensures consistent site naming across files.

Step 4: build a Review sheet that shows completeness and exceptions

Instead of relying on people to “scan the table,” create a Review sheet that answers: “Is this log ready to submit?” Use Power Query to generate an exceptions table that lists rows with missing required fields or invalid values.

Approach:

- Create a Power Query that reads tblReceivingLog.

- In Power Query, enforce data types (date for LogDate, whole number for QtyReceived, etc.).

- Add conditional columns that flag missing required fields (e.g., Supplier is null/blank, SKU is null/blank, QtyReceived is null).

- Filter to only rows where any flag is true.

- Load the result to the Review sheet as tblExceptions.

Users now have a single place to fix issues before submission, reducing back-and-forth later.

Step 5: standardize the output for appending

Create a second Power Query that outputs the clean dataset with the canonical schema and correct types. This is the dataset that will be appended into the master history. Load it to an Output sheet as a table like tblReceivingOutput.

Key idea: do not append the raw input table directly. Always append the standardized query output. This prevents rework caused by inconsistent types (dates stored as text, quantities stored as text, extra spaces in codes).

Step 6: folder-based ingestion for the master dataset

Set up a master workbook that uses Power Query to combine all site files in a folder. Each site drops its daily log file into the folder. The master query:

- Connects to the folder

- Filters to the correct file pattern (e.g., ReceivingLog_*.xlsx)

- Extracts the standardized output table from each file

- Appends all rows into a single fact table

This eliminates manual copy/paste consolidation and reduces rework when files arrive late or out of order—refresh pulls everything consistently.

Step-by-step: build a processing template for messy exports

Processing templates reduce rework by turning “weekly cleanup” into a refresh. The pattern is: land raw files in a folder, transform them with Power Query, and output a standardized dataset that downstream dashboards can rely on.

Step 1: define the raw-to-standard mapping

Take one representative export and list:

- Raw column names

- Standard column names you want

- Transformations needed (split, trim, replace, type conversion)

- Reference joins needed (e.g., map SKU to category, map location to region)

This mapping becomes your transformation spec. It prevents “tribal knowledge” cleanup steps that cause rework when someone new takes over.

Step 2: use a staging query and a final query

In Power Query, separate your logic into two layers:

- Staging query: minimal cleanup (remove top rows, promote headers, set types, trim/clean text, standardize date formats).

- Final query: business logic (derive fields, join reference tables, filter to relevant records, group/aggregate if needed).

This separation reduces rework because when the export format changes, you usually only adjust the staging layer while keeping business logic stable.

Step 3: parameterize the parts that change

Operational exports change: file names, date ranges, site filters. Instead of editing queries each time, store parameters in cells (e.g., StartDate, EndDate, SiteFilter) and read them into Power Query. This makes the template usable by others without breaking it.

Step 4: output a standardized table for dashboards

Load the final query to a table with stable column names and types. Downstream dashboards should connect to this output, not to the raw export. This reduces rework because dashboard fixes are no longer needed every time the export arrives with slightly different formatting.

Embedding operational checklists and handoff rules inside the template

Many operational errors are not “Excel errors” but process misses: someone forgets to attach a file, forgets to refresh queries, or submits without reviewing exceptions. Templates can reduce this rework by including a lightweight checklist and clear handoff rules.

Checklist pattern: “Ready to Submit” panel

Create a small panel on the Input or Review sheet that answers yes/no questions:

- All required fields complete?

- No exceptions remaining?

- Data refreshed?

- File named correctly?

- Saved to the correct folder?

Implement the checks using simple counts from the exception table and last refresh timestamps (Power Query can load a refresh log table if you maintain one). The goal is not to police users; it is to prevent avoidable rework.

Handoff rules: define what “done” means

Write explicit rules near the checklist, such as:

- Submit only when Exceptions = 0

- File name format: ReceivingLog_Site_YYYY-MM-DD.xlsx

- Save location: \Operations\Logs\Receiving\SiteName\

- Cutoff time: 10:00 next day

These rules reduce rework caused by inconsistent naming and misplaced files that break folder ingestion.

Standardizing across sites and teams without creating a brittle template

Standardization fails when templates are too rigid for real operations. The solution is to standardize the schema and outputs while allowing controlled variation through reference data and parameters.

Use reference tables for controlled variation

Instead of hardcoding values (like reason codes or shift names) into formulas or query steps, store them in reference tables that can be updated without redesigning the template. Power Query can merge these references during refresh to enrich the dataset.

Examples of controlled variation:

- Site-specific shift schedules

- Supplier lists by region

- SKU-to-category mappings that change over time

- Disposition rules for discrepancies

Design for “new codes” without breaking

Operational reality: a new supplier appears, a new SKU is introduced, a new discrepancy reason is needed. If the template breaks or requires manual rework, adoption drops. Build a process for unknowns:

- Allow an “Other/Unknown” option for categorical fields where appropriate.

- Capture unknown values in a separate query output (e.g., “Unmapped SKUs”) so the reference table can be updated.

- Keep the canonical schema stable even when codes expand.

This reduces rework by turning surprises into a controlled update cycle rather than an emergency fix.

Operational naming conventions that enable automation

Rework often comes from file chaos: inconsistent names, multiple versions, and unclear status. Naming conventions are a template feature, not an afterthought.

File naming convention

Use a consistent pattern that supports sorting and filtering:

- ProcessName_Site_YYYY-MM-DD.xlsx

- ProcessName_Site_YYYY-WW.xlsx (for weekly)

- ProcessName_Site_YYYY-MM.xlsx (for monthly)

Include the date in ISO order (YYYY-MM-DD) so files sort correctly. Avoid spaces and special characters to reduce issues with systems and scripts.

Sheet and table naming convention

Standardize internal names so Power Query and other workbooks can reliably extract the right objects:

- Input table: tblProcessInput

- Output table: tblProcessOutput

- Exceptions: tblProcessExceptions

- Reference tables: refSuppliers, refSKUs, refReasonCodes

Stable names reduce rework when templates are copied, shared, or combined across teams.

Template maintenance: change control without slowing operations

Templates that reduce rework must be maintained carefully. Uncontrolled edits create “template drift,” where different versions produce different outputs, forcing manual reconciliation.

Versioning inside the template

Store TemplateVersion in a visible place and include it in the output dataset as a column (e.g., TemplateVersion). This allows the master dataset to identify which version produced which rows, making troubleshooting faster.

Central distribution and protected structure

Distribute templates from a single source location and discourage local redesign. Protect structural elements that should not change (query outputs, reference table headers, output schema). Allow edits only where operational input is expected.

Change process for schema updates

When you must change the schema (add a column, rename a field), treat it as a controlled release:

- Update the template and increment TemplateVersion

- Update the master ingestion query to accept the new column (or handle both versions)

- Communicate the change and the effective date

- Optionally, keep a compatibility window where both old and new templates are accepted

This avoids rework caused by broken refreshes and inconsistent historical data.

Practical example: building an “Issue Tracker” operational template that feeds a dashboard

Consider an operations issue tracker used by supervisors to log blockers and follow-ups. The rework risks are common: inconsistent categories, missing owners, unclear due dates, and duplicated issues across shifts.

Define the workflow

- Log issue during shift

- Assign category and severity

- Assign owner and due date

- Update status during daily huddle

- Close issue with resolution code

- Dashboard tracks aging, backlog, recurring categories

Template structure

- Input: tblIssues (IssueID, Site, CreatedDate, Shift, Category, Severity, Description, Owner, DueDate, Status, ClosedDate, ResolutionCode)

- Reference: refCategories, refOwners, refResolutionCodes, refStatus

- Review: exceptions (missing owner, due date in past for open issues, status closed without closed date)

- Output: standardized issues table for folder ingestion

Power Query checks that reduce rework

In the Review query, implement operational rules as flags:

- Status = “Closed” and ClosedDate is null

- Status in (“Open”, “In Progress”) and DueDate is null

- DueDate < CreatedDate

- Description length too short (e.g., < 10 characters) indicating low-quality entries

- Category not found in refCategories (unmapped category)

Load these flagged rows to the Review sheet. The supervisor fixes issues before the file is dropped into the ingestion folder, preventing dashboard noise and follow-up questions.

Implementation notes: Power Query patterns that make templates robust

Keep query steps readable and stable

Name steps clearly (e.g., RenamedColumns, ChangedTypes, TrimmedText, MergedRefSKUs). Avoid unnecessary steps that make maintenance harder. A processing template is a shared asset; clarity reduces rework when someone else must modify it.

Prefer “transform at refresh” over “manual cleanup”

If a cleanup action is repeated more than twice, move it into Power Query. Examples: trimming spaces, replacing “N/A” with null, standardizing date formats, splitting combined fields, removing subtotal rows from exports.

Handle missing columns gracefully when possible

Exports sometimes drop or rename columns. Where feasible, design queries to be tolerant by checking for column existence and adding missing columns with nulls. This reduces rework during format changes and keeps operations running while the upstream export is fixed.

// Conceptual M pattern: add a column if missing (illustrative)

let

Source = ... ,

EnsureColumn = if List.Contains(Table.ColumnNames(Source), "DiscrepancyQty")

then Source

else Table.AddColumn(Source, "DiscrepancyQty", each null)

in

EnsureColumnUse this pattern selectively; you still want to know when upstream formats change, but you do not want operations to stop because a non-critical column disappeared.

Common failure modes (and how templates prevent them)

Failure mode: “Everyone has their own version”

Prevent with: embedded TemplateVersion, central distribution, stable table names, and folder ingestion that expects a known output table.

Failure mode: “The dashboard broke because the export changed”

Prevent with: staging/final query separation, parameterization, and standardized outputs that dashboards connect to.

Failure mode: “We spend hours cleaning data before we can use it”

Prevent with: capture templates that enforce schema, review sheets that surface exceptions, and Power Query transformations that run on refresh.

Failure mode: “We can’t trust the numbers”

Prevent with: explicit handoff rules, completeness checks, and exception-driven review outputs that make missing/invalid entries visible before consolidation.