Why these constructs matter in evolving domains

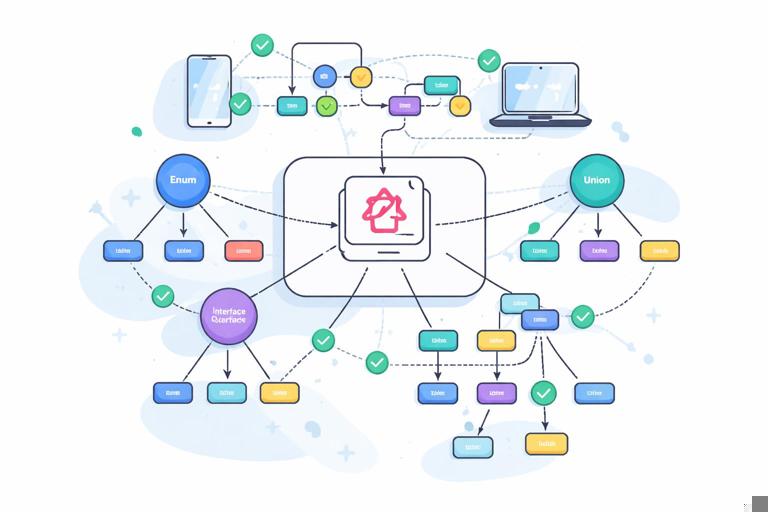

When a domain evolves, the hardest part is keeping your GraphQL schema expressive without forcing breaking changes on clients. Enums, interfaces, and unions are three modeling tools that help you represent variability: enums constrain a value to a known set, interfaces define a shared contract across multiple object types, and unions represent “one of several possible object types” without requiring shared fields. Used well, they let you add new capabilities by extending the schema rather than rewriting it, and they help clients write precise queries that match the shape of the data they actually need.

Modeling with enums: constrained values with predictable client behavior

What an enum is and when to use it

An enum is a scalar-like type whose value must be one of a predefined set of symbols. Enums are ideal for values that are stable, finite, and meaningful to clients: statuses, categories, roles, sort directions, or feature flags that are intentionally limited. Enums improve discoverability in tooling, prevent invalid values at runtime, and allow clients to branch logic safely because the set of possibilities is explicit.

Example: order status as an enum

Consider an order lifecycle. If you model status as a string, clients may see unexpected values and you lose schema-level validation. With an enum, you encode the contract directly.

enum OrderStatus { DRAFT SUBMITTED PAID FULFILLED CANCELED }Then use it on a type:

type Order { id: ID! status: OrderStatus! updatedAt: DateTime! }Clients can now query and handle the status with confidence, and GraphQL will reject invalid enum values in inputs automatically.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Step-by-step: introducing an enum safely

When you already have a string field in production, switching to an enum can be a breaking change. A safer migration is to introduce a new enum field and deprecate the old one.

- Step 1: Add the enum type and a new field, for example

statusV2: OrderStatus!. - Step 2: Keep the old

status: String!field but mark it deprecated. - Step 3: In resolvers, map existing string values to enum values. Decide how to handle unknown legacy values (for example map to

DRAFTor expose a dedicatedUNKNOWNenum value if that fits your domain). - Step 4: Update clients gradually to use

statusV2. - Step 5: Remove the deprecated field in a major version or when you control all clients.

type Order { id: ID! status: String! @deprecated(reason: "Use statusV2") statusV2: OrderStatus! }Evolving enums without breaking clients

Adding new enum values is generally backward compatible for the schema, but it can still break clients that assume they have handled every possible value. This is a client robustness issue rather than a schema compatibility issue. To reduce risk:

- Prefer “default” handling in clients (for example a fallback UI for unknown statuses).

- Avoid removing or renaming enum values; treat them as part of your public API.

- If you must retire a value, keep it but stop producing it; optionally document it as deprecated in descriptions (GraphQL does not support deprecating enum values in the core spec consistently across tooling).

Enums in inputs: sorting, filtering, and feature switches

Enums shine in input objects because they constrain behavior. For example, a search API might allow a limited set of sort keys and directions.

enum OrderSortField { CREATED_AT UPDATED_AT TOTAL_AMOUNT } enum SortDirection { ASC DESC } input OrderSort { field: OrderSortField! direction: SortDirection! }This prevents clients from sending arbitrary strings like "craetedAt" and makes the API self-documenting.

Modeling with interfaces: shared contracts across multiple types

What an interface is and when to use it

An interface defines a set of fields that multiple object types must implement. Interfaces are useful when different entities share common fields and behavior, and you want clients to query those shared fields uniformly while still being able to access type-specific fields via inline fragments. Interfaces are also a strong tool for evolving domains where new entity types appear over time but should still participate in common UI patterns (for example “things with an ID and a display name”).

Example: a Node interface for global identification

A common pattern is a Node interface that provides a stable id field across many types. This supports generic caching and client-side normalization.

interface Node { id: ID! } type User implements Node { id: ID! email: String! displayName: String! } type Order implements Node { id: ID! statusV2: OrderStatus! totalAmount: Money! }Clients can write queries that accept a Node and then branch by concrete type.

query GetNode($id: ID!) { node(id: $id) { id ... on User { displayName } ... on Order { statusV2 } } }Step-by-step: extracting an interface from duplicated fields

As domains evolve, you often notice repeated fields across types: createdAt, updatedAt, createdBy, or title. An interface can unify those fields without forcing a single “base type” in your backend model.

- Step 1: Identify a stable set of fields that truly mean the same thing across types (same semantics, not just same name).

- Step 2: Create an interface with those fields, for example

interface Audited { createdAt: DateTime! updatedAt: DateTime! }. - Step 3: Update each type to

implements Auditedand ensure resolvers can provide the fields. - Step 4: Update queries where clients currently fetch those fields from multiple types; they can now query them through the interface selection when the parent field returns the interface.

interface Audited { createdAt: DateTime! updatedAt: DateTime! } type Product implements Node & Audited { id: ID! createdAt: DateTime! updatedAt: DateTime! name: String! } type Order implements Node & Audited { id: ID! createdAt: DateTime! updatedAt: DateTime! statusV2: OrderStatus! }Interface return types vs. unions

If clients need to rely on shared fields across the possible types, prefer an interface. For example, a feed of “activities” might always show a timestamp and an actor, regardless of the activity kind. An interface lets clients query those shared fields without fragments for every type.

interface Activity { id: ID! occurredAt: DateTime! actor: User! } type OrderPlaced implements Activity { id: ID! occurredAt: DateTime! actor: User! order: Order! } type CommentAdded implements Activity { id: ID! occurredAt: DateTime! actor: User! comment: Comment! }Clients can query:

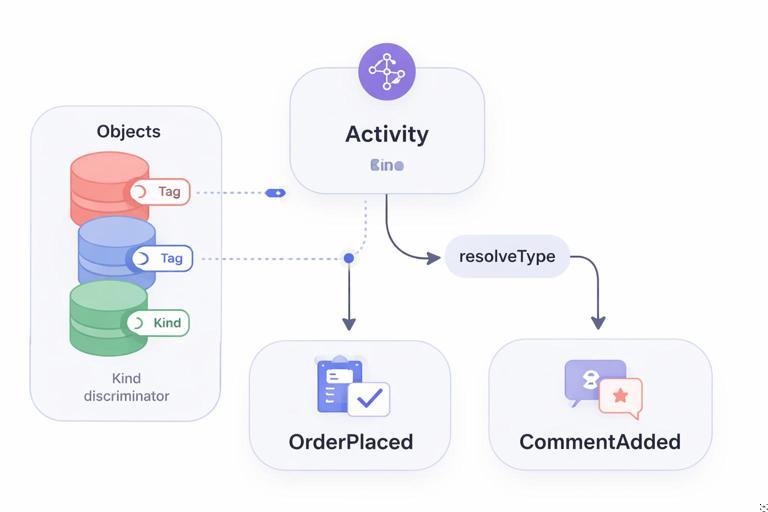

query Feed { activityFeed { id occurredAt actor { id displayName } ... on OrderPlaced { order { id statusV2 } } ... on CommentAdded { comment { id body } } } }Resolver considerations: type resolution for interfaces

At runtime, GraphQL needs to know which concrete type an interface value represents. Most server frameworks require either a per-type isTypeOf function or a central resolveType function on the interface. In evolving domains, a robust approach is to include a backend “kind” discriminator and map it to GraphQL types.

// Pseudocode-ish resolver sketch Activity: { __resolveType(obj) { switch (obj.kind) { case "ORDER_PLACED": return "OrderPlaced" case "COMMENT_ADDED": return "CommentAdded" default: return null // triggers a runtime error if returned value can't be typed } } }Plan for unknown kinds: if your backend can produce new kinds before the GraphQL schema is updated, you will get runtime errors. In practice, you should deploy schema updates before producing new kinds, or gate new kinds behind feature flags until the schema supports them.

Modeling with unions: “one of” types without shared fields

What a union is and when to use it

A union is a type that can be one of several object types, but it does not define shared fields. Clients must use inline fragments to select fields from each possible member type. Unions are best when the member types are conceptually different and do not share a meaningful common contract, or when forcing shared fields would be artificial and misleading.

Example: search results across unrelated entities

A classic use case is a global search that can return users, orders, and products. These entities do not share a clean set of fields beyond perhaps id, but even id might not be globally unique unless you enforce it. A union keeps the schema honest.

union SearchResult = User | Order | Product type Query { search(query: String!): [SearchResult!]! }Client query:

query Search($q: String!) { search(query: $q) { __typename ... on User { id displayName } ... on Order { id statusV2 totalAmount { amount currency } } ... on Product { id name } } }Step-by-step: designing a union-based API that remains extensible

Unions are naturally extensible because you can add new member types later. To do that safely and predictably:

- Step 1: Make sure clients always request

__typenamefor union selections so they can branch on the concrete type. - Step 2: Document the expected set of types and encourage a default handling path for unknown types.

- Step 3: Add new union members only when clients can tolerate them. If some clients are strict, consider versioning the field (for example

searchV2) or adding an argument that scopes which types are returned. - Step 4: Keep union members as object types (GraphQL unions cannot include interfaces directly; they include object types).

Resolver considerations: type resolution for unions

Like interfaces, unions require runtime type resolution. The same discriminator approach works well. If your search backend returns heterogeneous results, include a type field in each hit and map it to the GraphQL type name.

// Pseudocode-ish resolver sketch SearchResult: { __resolveType(obj) { if (obj.type === "user") return "User" if (obj.type === "order") return "Order" if (obj.type === "product") return "Product" return null } }Choosing between enum, interface, and union in real domain changes

Scenario 1: a status field grows into a richer state machine

Many domains start with a simple status string, then grow into something more complex: timestamps per transition, reasons, and actor information. An enum can still represent the current state, but you may also introduce a structured object to capture details without breaking existing clients.

enum TicketStatus { OPEN IN_PROGRESS RESOLVED CLOSED } type TicketStatusInfo { status: TicketStatus! changedAt: DateTime! changedBy: User reason: String } type Ticket { id: ID! status: TicketStatus! statusInfo: TicketStatusInfo! }This keeps the simple status field for common UI needs while enabling richer workflows through statusInfo. As the domain evolves further, you can add fields to TicketStatusInfo without changing the enum itself.

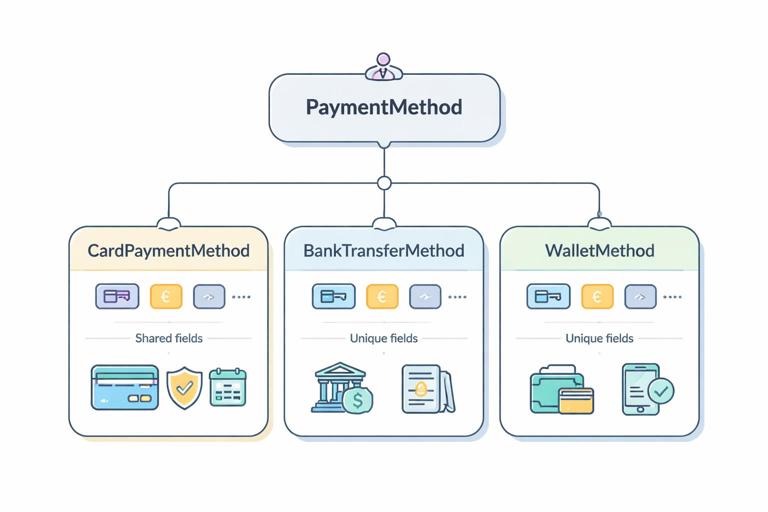

Scenario 2: multiple “payment methods” with shared fields and specialized details

Suppose you support card payments, bank transfers, and digital wallets. They share some fields (like id, provider, and lastUsedAt), but each has unique fields. This is a good fit for an interface if the shared fields are meaningful to clients.

enum PaymentProvider { STRIPE ADYEN PAYPAL } interface PaymentMethod { id: ID! provider: PaymentProvider! lastUsedAt: DateTime } type CardPaymentMethod implements PaymentMethod { id: ID! provider: PaymentProvider! lastUsedAt: DateTime brand: String! last4: String! expMonth: Int! expYear: Int! } type BankTransferMethod implements PaymentMethod { id: ID! provider: PaymentProvider! lastUsedAt: DateTime bankName: String! ibanLast4: String! } type WalletMethod implements PaymentMethod { id: ID! provider: PaymentProvider! lastUsedAt: DateTime walletEmail: String! }Clients can render a list of payment methods using the interface fields, then branch for details:

query PaymentMethods { me { paymentMethods { id provider lastUsedAt ... on CardPaymentMethod { brand last4 } ... on BankTransferMethod { bankName ibanLast4 } ... on WalletMethod { walletEmail } } } }Scenario 3: error modeling that evolves over time

As you add business rules, you may want to return structured errors with different shapes. A union can represent multiple error types cleanly, especially when they do not share a meaningful set of fields beyond a message. If they do share fields (like code and message), an interface can be better. Here is a union approach for distinct error payloads.

type ValidationError { message: String! field: String! } type PermissionError { message: String! requiredRole: String! } type RateLimitError { message: String! retryAfterSeconds: Int! } union CheckoutError = ValidationError | PermissionError | RateLimitError type CheckoutResult { ok: Boolean! errors: [CheckoutError!]! }Clients must use fragments to read each error shape, and can always read __typename to branch.

Practical patterns for long-lived schemas

Pattern: pair enums with descriptive objects for extensibility

Enums are great for stable categories, but they are not extensible in the same way objects are. A practical pattern is to keep an enum for the “primary” classification and add an object for metadata that can grow. For example, keep status as an enum, and add statusDetails as an object with timestamps, actors, and optional fields. This avoids turning the enum into a dumping ground for every nuance.

Pattern: use interfaces to stabilize cross-cutting concerns

Interfaces help you keep cross-cutting concerns consistent as the domain grows: audit fields, ownership, visibility, and presentation. If your UI repeatedly needs title and thumbnailUrl across different content types, define a CardRenderable interface and implement it on each type. This reduces client branching and makes it easier to add new content types later without rewriting the UI query shape.

interface CardRenderable { id: ID! title: String! thumbnailUrl: String } type Article implements CardRenderable { id: ID! title: String! thumbnailUrl: String body: String! } type Video implements CardRenderable { id: ID! title: String! thumbnailUrl: String durationSeconds: Int! }Pattern: use unions for aggregation boundaries

Unions are particularly effective at aggregation boundaries: search, activity streams, notifications, and “inbox” style experiences. These are places where the backend is intentionally combining unrelated entities. A union communicates that heterogeneity clearly and avoids inventing fake shared fields just to satisfy an interface.

Pattern: design for unknown future members

For interfaces and unions, clients should treat the set of concrete types as open-ended. Encourage client code to handle an unknown __typename gracefully (for example render a generic card). On the server, add new types in a way that does not surprise clients: roll out schema support first, then start returning the new type, and consider arguments that let clients opt into new categories of results.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

Pitfall: using enums for user-generated or frequently changing values

If values are created by users (tags, categories, custom statuses) or change frequently, an enum will force constant schema updates and deployments. In those cases, model the value as an object type (for example Category) with an id and name, and reference it from other types. Reserve enums for values you control and intend to keep stable.

Pitfall: forcing an interface where semantics don’t match

Two types may share field names but not meaning. For example, status on an order and status on a user account might have different lifecycles and interpretations. If you create an interface just because fields look similar, you can mislead clients into assuming they are interchangeable. Only extract an interface when the fields represent the same concept.

Pitfall: unions without __typename in client queries

When clients query a union but forget __typename, they often end up with brittle branching logic based on which fragment returned data. Make it a habit to request __typename whenever you query a union or interface selection, especially in list views and caches.

Pitfall: runtime type resolution drift

Interfaces and unions rely on correct runtime type resolution. If your backend returns objects that do not match any known GraphQL type, queries will error. Keep a tight contract between your domain discriminators and your GraphQL schema, and add monitoring for type resolution failures so you catch mismatches quickly during rollouts.