What “HTML as the Application Surface” Means

In a hypermedia-driven application, the primary “surface area” of your app is not a JavaScript state container, a client-side router, or a bundle of view models. The surface is HTML: the elements the browser can render, the links and forms that express possible next actions, and the server responses that update the page. Thinking this way changes how you design features: you start by asking “What HTML should the user see next?” rather than “What client state should I mutate?”

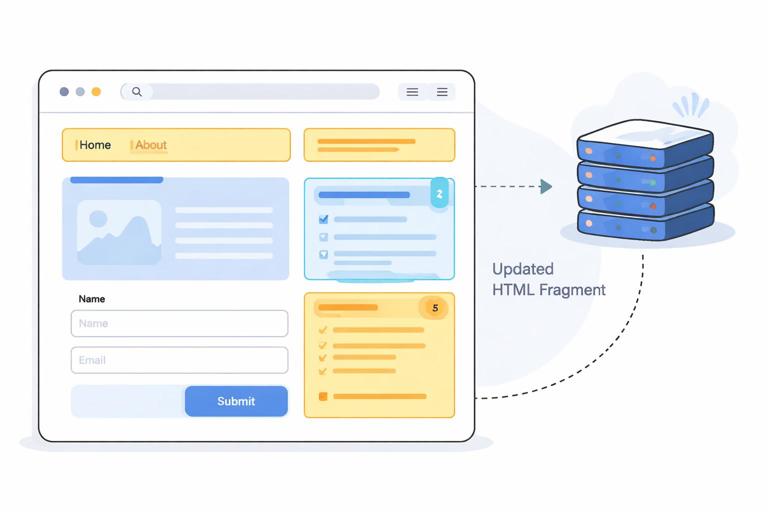

HTML as the application surface means you treat markup as the contract between client and server. The server is responsible for producing meaningful HTML for each state of the UI, and the client is responsible for requesting and swapping that HTML into place. With HTMX, those requests can be targeted and partial (a fragment replaces a region), and with Alpine.js, small bits of local interactivity can live close to the elements they affect. The result is an application that behaves like a modern UI without requiring the browser to own the entire application model.

Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State

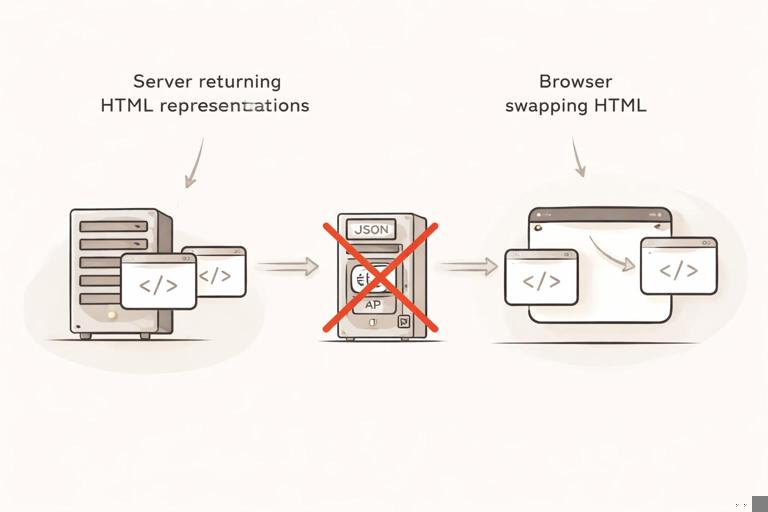

Hypermedia is more than “HTML pages.” It is a way to represent application state and transitions using media types the client understands (in this case, HTML). Links and forms are not just navigation; they are state transition affordances. A link says “you can go here next,” and a form says “you can submit this data to get a new representation.”

When you adopt hypermedia-driven thinking, you stop treating the server as a JSON vending machine and the browser as the “real app.” Instead, the server returns the next representation of the UI (often a partial), and the browser swaps it in. This keeps the client thin and makes the UI’s state transitions explicit in the markup.

Designing Features from the UI Backward

A practical way to internalize HTML-as-surface is to design from the UI backward. Start with a sketch of the HTML you want on screen, then identify which parts need to change in response to user actions. Those changeable regions become targets for HTMX swaps. Each user action becomes either a link click or a form submission (possibly enhanced by HTMX attributes). The server endpoints return HTML fragments that match the region being replaced.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

This approach naturally encourages cohesive, testable server handlers: each handler returns a representation (full page or fragment) that can be rendered and verified. It also reduces the need for complex client orchestration because the “what happens next” is encoded in the returned HTML and the attributes on the elements.

Step-by-Step: Turning a “SPA-Style” Interaction into Hypermedia

Consider a common SPA interaction: a list of items with a “Create” form and inline validation. In a client-heavy approach, you might keep an array of items in memory, optimistically update it, and handle validation errors by mapping server JSON into UI state. In a hypermedia-driven approach, you let the server be the source of truth and return HTML that already includes the updated list or the validation messages.

Step 1: Identify the stable layout and the replaceable regions

Start with a page that has a stable shell and two regions that change: the list and the form. The list updates when an item is added; the form updates when validation fails (to show errors) or after success (to clear inputs).

<main> <section> <h3>Items</h3> <div id="items-list"> <!-- server-rendered list fragment --> </div> </section> <section> <h3>Create Item</h3> <div id="item-form"> <!-- server-rendered form fragment --> </div> </section></main>Step 2: Make the form submit return HTML, not JSON

Instead of posting JSON and expecting JSON back, post the form normally (or via HTMX) and have the server respond with an HTML fragment. If the submission is successful, return the updated list fragment and optionally a fresh form fragment. If validation fails, return the form fragment with inline errors.

With HTMX, you can target exactly which region should be replaced. For example, submit the form and swap the form region with the server response (which might include errors or a cleared form).

<form hx-post="/items" hx-target="#item-form" hx-swap="outerHTML"> <label>Name</label> <input name="name" /> <button type="submit">Create</button></form>Now the server can return either a form with errors (same outer wrapper) or a fresh form. The browser doesn’t need to interpret error codes; it just swaps HTML.

Step 3: Trigger a list refresh as a separate hypermedia action

After a successful create, you want the list to update. You can do this in a few hypermedia-friendly ways. One common pattern is to have the form response include an out-of-band swap for the list. Another is to have the form response include an element that triggers a follow-up request. The key is that the server still returns HTML, and the client still swaps HTML.

Here is an out-of-band swap approach: the form response includes a fragment for the list marked to replace the list region, even though the request targeted the form.

<!-- server response to successful POST /items --><div id="item-form"> <form hx-post="/items" hx-target="#item-form" hx-swap="outerHTML"> <label>Name</label> <input name="name" value="" /> <button type="submit">Create</button> </form></div><div id="items-list" hx-swap-oob="outerHTML"> <ul> <li>New item</li> <!-- rest of items --> </ul></div>Notice what happened: the server returned the “next UI” as HTML. The browser performed swaps; no client-side list state was required.

Thinking in Representations: Full Pages and Fragments

HTML-as-surface encourages you to think in representations. A full page representation is what you’d return to a normal browser navigation. A fragment representation is what you’d return to an HTMX request targeting a region. Both are still HTML, and ideally they share templates/partials so you don’t duplicate markup.

A useful discipline is to ensure every fragment can be rendered independently and still make sense. That means including the wrapper element that will be swapped (for example, returning the entire <div id="item-form">...</div> when using outerHTML swaps). This keeps the swap predictable and reduces “mismatched DOM” bugs.

HTML as a Contract: What the Client Can Rely On

When HTML is the contract, you define stable IDs, predictable fragment boundaries, and consistent semantics. The client “relies” on the presence of a target element and the server “relies” on the browser to render and submit forms. HTMX attributes become part of that contract: they declare where requests go, what gets swapped, and what events should trigger requests.

This contract is simpler than a bespoke JSON schema plus client-side mapping logic. It is also easier to debug: you can inspect the HTML response and see exactly what the user will get next. If something is wrong, you fix the template or handler rather than chasing state synchronization issues across layers.

Local Interactivity with Alpine.js Without Owning the App

HTML-as-surface does not mean “no JavaScript.” It means JavaScript is used to enhance the surface, not to replace it. Alpine.js is a good fit for small, local behaviors: toggling a dropdown, showing a confirmation panel, managing a tab’s active state, or temporarily disabling a button while a request is in flight.

The key is scope: Alpine state should be local and disposable. If the server swaps out a region, the Alpine component inside it can be recreated from the new HTML. This aligns with hypermedia: the server is the source of truth, and the client’s interactive state is ephemeral and tied to the current representation.

Example: Confirm-before-delete as a local enhancement

Instead of building a global modal system with centralized state, you can embed a small confirmation UI next to each delete button. The delete itself remains a hypermedia action (a request that returns updated HTML).

<li x-data="{ confirming: false }"> <span>Item A</span> <button type="button" @click="confirming = true" x-show="!confirming">Delete</button> <span x-show="confirming"> <button hx-delete="/items/123" hx-target="#items-list" hx-swap="outerHTML">Confirm</button> <button type="button" @click="confirming = false">Cancel</button> </span></li>The delete action still returns HTML for the updated list. Alpine only manages the temporary “confirming” toggle.

Server-Side UI State vs Client-Side UI State

A frequent source of complexity in SPAs is duplicated state: the server has a database truth, and the client has a cached, partially updated truth. Hypermedia-driven apps reduce duplication by letting the server render the authoritative UI state. The client does not need to keep a canonical copy of lists, counters, or validation rules; it requests the next representation.

This does not eliminate all client state. It reframes it. Client state becomes: transient UI affordances (open/closed), input focus, optimistic affordances like “loading,” and small computed behaviors. Anything that must be consistent across sessions, users, or permissions belongs on the server and should be reflected in the HTML returned.

Step-by-Step: Modeling a Workflow as Linked Screens and Partial Updates

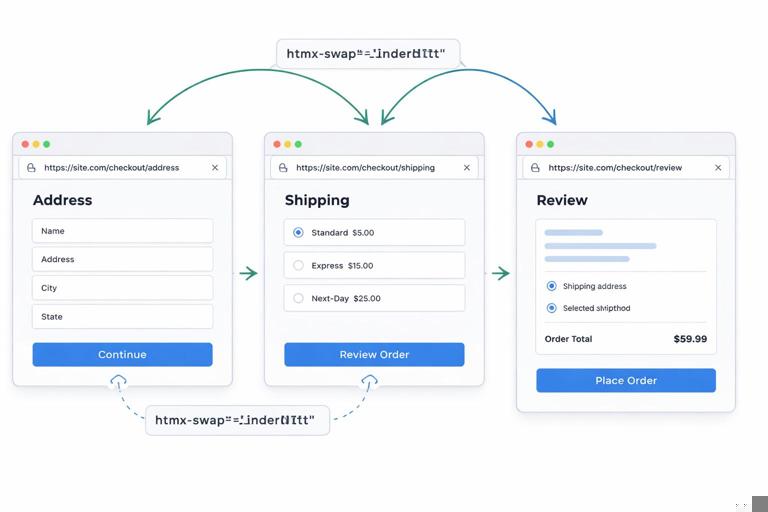

Workflows are where HTML-as-surface shines because each step can be a representation with clear transitions. Instead of a client-side wizard that conditionally renders steps based on a local state machine, you can model each step as a server-rendered view with links/forms that move forward or backward.

Step 1: Define each step’s representation

For example, a checkout-like flow might have “Address,” “Shipping,” and “Review.” Each step is a URL that returns a full page for normal navigation and can also return fragments for partial updates (like recalculating totals).

- GET /flow/address → address form

- POST /flow/address → validate and redirect/return next step

- GET /flow/shipping → shipping options

- POST /flow/shipping → save choice and return review

Step 2: Use forms as the state transition mechanism

Each step submits to the server. The server validates, persists, and returns the next representation. With HTMX, you can keep the page feeling fluid by swapping only the step container.

<div id="flow-step"> <form hx-post="/flow/address" hx-target="#flow-step" hx-swap="outerHTML"> <h3>Address</h3> <input name="street" /> <input name="city" /> <button type="submit">Continue</button> </form></div>If validation fails, the server returns the same step with error messages. If it succeeds, the server returns the shipping step HTML wrapped in the same #flow-step container. The client does not need a wizard state machine; the server is the workflow engine.

Step 3: Add partial recalculations as separate hypermedia endpoints

Sometimes a step needs dynamic recalculation, like updating totals when a shipping option changes. Instead of computing totals in client code, you can request a fragment from the server that renders the totals area.

<div id="shipping-options"> <label><input type="radio" name="ship" value="standard" hx-post="/flow/shipping/quote" hx-trigger="change" hx-target="#totals" /> Standard</label> <label><input type="radio" name="ship" value="express" hx-post="/flow/shipping/quote" hx-trigger="change" hx-target="#totals" /> Express</label></div><div id="totals"> <!-- server-rendered totals fragment --></div>The totals are now a representation the server owns. This avoids mismatches between client calculations and server rules (taxes, discounts, eligibility), and it keeps the UI consistent with what will actually be charged.

Progressive Enhancement as a Default, Not a Special Case

When HTML is the surface, progressive enhancement becomes natural. A link works as navigation without JavaScript. A form submits without JavaScript. HTMX enhances those interactions by making them partial and faster-feeling, but the underlying semantics remain. This has practical benefits: accessibility is easier to maintain, browser behaviors like back/forward are more predictable, and failure modes degrade gracefully.

To support this, structure your templates so that the default experience is a full page render, and then layer HTMX attributes to target regions. For example, the same form can work with a normal POST-redirect-GET cycle, while HTMX requests can return fragments. The server can detect HTMX requests via headers and choose an appropriate template, but the core action remains the same.

Practical Template Strategy: One Source of Markup

To keep HTML-as-surface maintainable, avoid duplicating markup between full pages and fragments. A practical strategy is to create partial templates for each swap region (list, form, totals, step container) and include them in both full-page templates and fragment responses.

The goal is that the fragment returned to HTMX is the same markup that appears inside the full page. This ensures consistency and reduces the risk that the “HTMX path” and the “full navigation path” diverge. It also makes it easier to test: render the full page in a browser, then verify that fragment endpoints return the same DOM subtree you expect to swap.

Event-Driven UI Without a Client Event Bus

In many SPAs, cross-component coordination leads to event buses, global stores, and complex dependency graphs. Hypermedia-driven apps can often avoid that by letting the server coordinate via returned HTML. If one action affects multiple regions, the server can return multiple fragments (for example, using out-of-band swaps) so the UI updates coherently.

This shifts coordination from “client components talking to each other” to “the server returning a coherent representation.” The client becomes a renderer and swapper. When you do need client-side coordination, keep it close to the DOM using Alpine and HTMX events, but treat it as an enhancement rather than the backbone of the application.

Debugging and Testing with HTML as the Artifact

When the primary artifact is HTML, debugging becomes more concrete. You can reproduce issues by requesting the endpoint and inspecting the returned markup. You can log or snapshot the fragment responses. You can write server-side tests that assert specific elements, IDs, and error messages are present. This is often simpler than testing a client-side state machine plus API responses plus rendering logic.

A practical habit is to treat each fragment endpoint as a “mini page” that can be rendered in isolation. If a fragment is supposed to replace #items-list, ensure the response contains a single root element with id="items-list". If a fragment is supposed to replace a form wrapper, ensure it returns that wrapper. These small invariants make HTMX swaps predictable and keep your UI stable as features grow.