Why error handling needs a strategy

GraphQL always returns an HTTP response, often with status 200, even when part of the operation fails. That design enables partial success: some fields can resolve while others fail. Without a deliberate strategy, clients receive inconsistent shapes, ambiguous messages, and accidental leakage of internal details (stack traces, database errors, service names). A good strategy defines which failures are expected, how they are represented, what is safe to show to clients, and how to make failures observable for operators without exposing internals.

GraphQL error anatomy: what the client actually sees

A GraphQL response can contain a data object, an errors array, or both. Each error may include message, path, and locations, and can include an extensions object for structured metadata. The path is crucial: it tells the client which field failed so the UI can degrade gracefully. The extensions object is where you should put client-safe codes and correlation identifiers, not raw exception details.

{

"data": {

"viewer": {

"id": "u1",

"email": null

}

},

"errors": [

{

"message": "Not authorized to access email",

"path": ["viewer", "email"],

"extensions": {

"code": "FORBIDDEN",

"requestId": "req_7f3c..."

}

}

]

}Failure modes: transport, GraphQL execution, and business errors

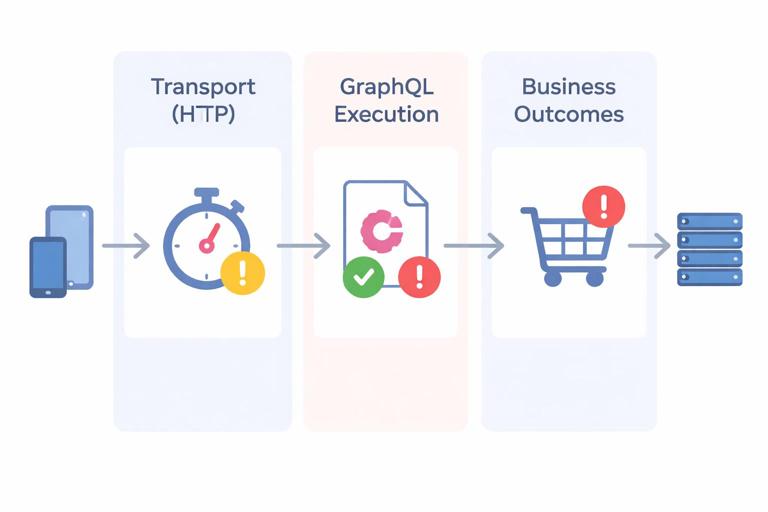

To keep behavior predictable, separate failures into three buckets. Transport failures are HTTP-level problems (timeouts, gateway errors, invalid JSON) and are not GraphQL-specific; clients handle them with retry/backoff and user messaging. Execution failures are GraphQL runtime issues (validation errors, missing required variables, resolver exceptions) that appear in the GraphQL errors array. Business errors are domain-level outcomes (insufficient funds, username taken) that are not “exceptional” from a product perspective and should be modeled intentionally so clients can render them without guessing.

When to use GraphQL errors vs modeled business results

Use GraphQL errors for unexpected failures and access control violations where the field cannot be resolved. Use modeled business results when the operation completed successfully from a system perspective but the requested change cannot be applied due to domain rules. This distinction prevents clients from treating normal product flows as crashes and reduces noisy alerting.

Client-safe error design with codes, not strings

Error messages are for humans; error codes are for software. Clients should branch on stable codes, not on English text. Define a small, consistent set of error codes that apply across the API, and use them in extensions.code for GraphQL errors and in typed payloads for business outcomes. Keep codes coarse enough to remain stable, but specific enough to drive UI decisions.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Recommended baseline error codes

- BAD_USER_INPUT: validation failures, malformed IDs, missing required inputs.

- UNAUTHENTICATED: no valid session/token.

- FORBIDDEN: authenticated but not allowed.

- NOT_FOUND: resource does not exist or is not visible (be careful with enumeration).

- CONFLICT: version mismatch, uniqueness violations, concurrent updates.

- RATE_LIMITED: throttling decisions.

- INTERNAL: unexpected server-side failure.

- DEPENDENCY_FAILED: downstream service failure (optional, if you want clients to show “try again”).

What is safe to include in extensions

Client-safe metadata typically includes code, a requestId or traceId, and sometimes a retryAfterMs for throttling. Avoid including stack traces, SQL errors, hostnames, internal service URLs, or raw exception class names. If you need to expose details for debugging, gate them behind a server-side feature flag and only enable them in non-production environments.

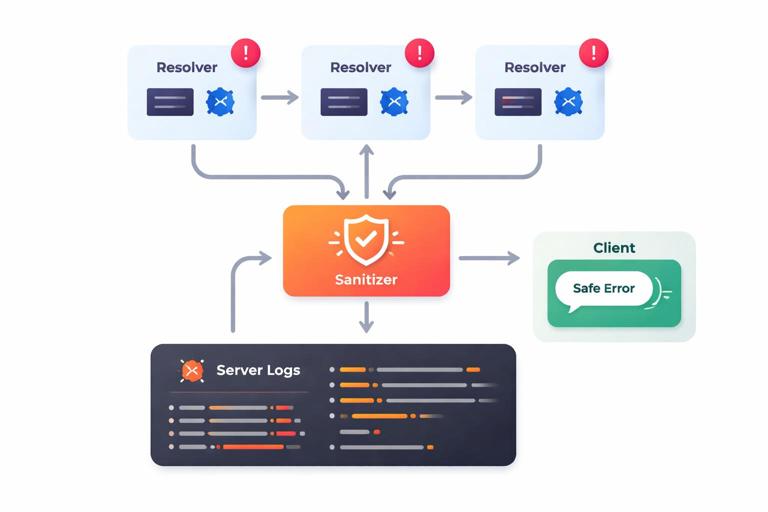

Step-by-step: implement a server error normalization layer

The goal is to ensure every thrown error becomes a predictable, sanitized GraphQL error. Most GraphQL servers provide a hook (often called formatError or an error plugin) where you can map internal exceptions to safe outputs. The steps below are framework-agnostic and focus on the behavior you want.

Step 1: define internal error types

Create a small set of internal exception classes (or error objects) that represent the categories you care about: authentication, authorization, validation, conflict, and internal. Each should carry a stable code and optionally safe metadata. This avoids sprinkling ad-hoc string messages across resolvers.

class AppError extends Error {

constructor(message, { code = "INTERNAL", httpStatus, safeExtensions = {} } = {}) {

super(message);

this.code = code;

this.httpStatus = httpStatus;

this.safeExtensions = safeExtensions;

}

}

class ForbiddenError extends AppError {

constructor(message = "Forbidden", safeExtensions = {}) {

super(message, { code: "FORBIDDEN", safeExtensions });

}

}

class BadUserInputError extends AppError {

constructor(message = "Invalid input", safeExtensions = {}) {

super(message, { code: "BAD_USER_INPUT", safeExtensions });

}

}Step 2: throw internal errors from resolvers, not raw exceptions

In resolvers, convert known failure conditions into your internal error types. For unknown exceptions, let them bubble up so the global formatter can treat them as INTERNAL. This keeps resolver code readable and ensures consistent output.

async function updateEmail(_, { input }, ctx) {

if (!ctx.user) throw new AppError("Unauthenticated", { code: "UNAUTHENTICATED" });

if (!input.email.includes("@")) throw new BadUserInputError("Email is invalid", { field: "email" });

const canEdit = await ctx.authz.canEditUser(ctx.user.id);

if (!canEdit) throw new ForbiddenError("Not allowed to update email");

try {

return await ctx.userService.updateEmail(ctx.user.id, input.email);

} catch (e) {

// Let unexpected errors be handled centrally

throw e;

}

}Step 3: normalize and sanitize in a single place

Implement a formatter that maps any error into a safe GraphQL error. Always attach a correlation ID. Always set a stable code. Replace unknown messages with a generic one. Log the original error server-side with the correlation ID so operators can trace it.

function formatGraphQLError(err, { requestId, isProd }) {

const original = err.originalError || err;

// Default safe output

let message = "Something went wrong";

let code = "INTERNAL";

let extensions = { requestId };

if (original && original.code) {

code = original.code;

message = original.message; // assumed safe for known AppErrors

extensions = { ...extensions, ...original.safeExtensions };

}

// Never leak internals in production

if (!isProd) {

extensions.debug = {

name: original.name,

stack: original.stack

};

}

return {

message,

path: err.path,

extensions: { code, ...extensions }

};

}Step 4: decide how HTTP status codes are used

Many GraphQL deployments return HTTP 200 for application-level errors, relying on the errors array. That is acceptable, but you should still use non-200 statuses for transport-level failures (invalid JSON, unsupported method) and optionally for request-wide GraphQL failures (query parsing/validation errors) if your gateway and clients benefit from it. If you do vary HTTP status, document it clearly and keep it consistent across environments.

Client-safe partial failures and nullability

GraphQL’s nullability rules determine how failures propagate. If a resolver for a nullable field fails, that field becomes null and an error is added. If a resolver for a non-null field fails, GraphQL will null out its parent, potentially cascading up to the root. This can be surprising to clients and can turn a small issue into a blank screen. Error strategy therefore includes schema decisions: choose non-null only when you can truly guarantee the field or when you want to fail fast.

Practical guidance for nullability and resilience

- Make fields nullable when they depend on permissions, optional integrations, or best-effort enrichment.

- Use non-null for identifiers and invariants that must exist when the parent object exists.

- For fields that may fail due to downstream dependencies, prefer nullable plus a structured error code so the UI can show a fallback.

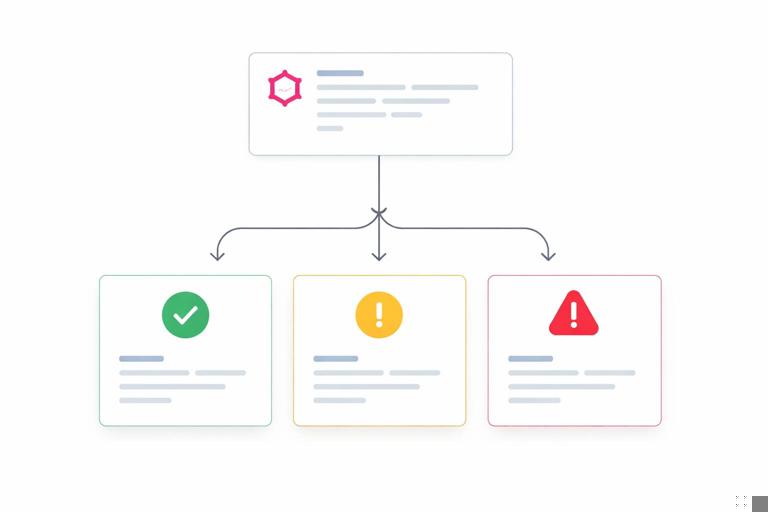

Modeling business failures with typed results

For mutations and some queries, a typed result pattern makes client behavior explicit. Instead of throwing an error for a domain rule, return a union (or interface) of success and failure types. This keeps “expected failures” out of the GraphQL errors array and avoids confusing partial data with broken execution.

union UpdateEmailResult = UpdateEmailSuccess | ValidationError | ConflictError

type UpdateEmailSuccess {

user: User!

}

type ValidationError {

code: String! # e.g., BAD_USER_INPUT

field: String

message: String!

}

type ConflictError {

code: String! # e.g., CONFLICT

message: String!

}In this approach, the client checks __typename and handles each case. The server still uses GraphQL errors for truly exceptional situations (timeouts, bugs, permission checks that prevent even returning a meaningful result).

Step-by-step: implement typed mutation outcomes

First, decide which failures are part of normal product flow (validation, conflicts, preconditions). Second, define result types with stable codes and minimal safe fields. Third, implement resolvers that return these objects instead of throwing. Fourth, reserve thrown errors for authentication/authorization and unexpected exceptions.

async function updateEmail(_, { input }, ctx) {

if (!ctx.user) throw new AppError("Unauthenticated", { code: "UNAUTHENTICATED" });

if (!input.email.includes("@")) {

return { __typename: "ValidationError", code: "BAD_USER_INPUT", field: "email", message: "Email is invalid" };

}

const ok = await ctx.userService.tryUpdateEmail(ctx.user.id, input.email);

if (!ok) {

return { __typename: "ConflictError", code: "CONFLICT", message: "Email already in use" };

}

const user = await ctx.userService.getById(ctx.user.id);

return { __typename: "UpdateEmailSuccess", user };

}Validation errors: field-level details without leaking internals

Clients often need to highlight specific input fields. Provide field-level validation details in a structured way, but keep them generic and safe. Avoid echoing back sensitive values (like passwords) or revealing exact constraints that help attackers (for example, “user exists” vs “invalid credentials”). For GraphQL errors, include extensions.field or extensions.validation. For typed results, include field and a stable code.

{

"message": "Invalid input",

"extensions": {

"code": "BAD_USER_INPUT",

"validation": [

{ "field": "email", "rule": "FORMAT" },

{ "field": "age", "rule": "MIN" }

],

"requestId": "req_..."

}

}Authentication and authorization: safe failure semantics

Auth failures are common and must be consistent. Prefer UNAUTHENTICATED when there is no valid identity, and FORBIDDEN when the identity is known but lacks permission. Consider whether to return NOT_FOUND instead of FORBIDDEN for certain resources to reduce enumeration risk; if you do, apply it consistently and document it so clients do not mis-handle it.

Field-level authorization and partial data

GraphQL encourages fetching many fields at once, and different fields may have different permissions. Decide whether unauthorized fields should return null with a FORBIDDEN error at that path, or whether the entire object should be hidden. The first approach supports richer UIs but can create noisy errors; the second reduces error volume but may require additional queries. Whichever you choose, keep it consistent across the schema so clients can predict behavior.

Rate limiting and throttling: client-friendly signals

When you throttle, clients need to know whether to retry and when. Use a stable code like RATE_LIMITED and include a safe retry hint such as retryAfterMs in extensions. If your infrastructure supports it, also set HTTP headers like Retry-After for request-wide throttling, but do not rely on headers alone because GraphQL clients often operate at the field level.

{

"message": "Too many requests",

"extensions": {

"code": "RATE_LIMITED",

"retryAfterMs": 1500,

"requestId": "req_..."

}

}Downstream dependency failures and graceful degradation

GraphQL servers frequently aggregate multiple backends. If a downstream dependency fails, decide whether to fail the whole operation or return partial data. For non-critical enrichments (recommendations, optional analytics, secondary profile data), prefer nullable fields and return a DEPENDENCY_FAILED code at the field path. For critical dependencies (payment authorization during checkout), fail the mutation with a clear, client-safe error code and message that encourages retry or alternate action.

Step-by-step: wrap downstream calls with error mapping

First, classify each downstream call as critical or best-effort. Second, wrap calls in a helper that catches timeouts and known error responses. Third, map them to either typed business results (if expected) or GraphQL errors with safe codes (if exceptional). Fourth, log the raw downstream error with request correlation so operators can diagnose without exposing internals to clients.

async function fetchRecommendations(userId, ctx) {

try {

return await ctx.recoService.getForUser(userId);

} catch (e) {

ctx.logger.warn({ requestId: ctx.requestId, err: e }, "reco service failed");

throw new AppError("Recommendations unavailable", {

code: "DEPENDENCY_FAILED",

safeExtensions: { dependency: "recommendations" }

});

}

}Observability: correlate client errors with server logs

Client-safe errors should still be actionable. Always attach a requestId (or trace ID) to every error and include it in server logs. If you use distributed tracing, propagate trace context from the edge to resolvers and downstream calls. In logs, record the original exception, stack trace, and relevant resolver path, but keep sensitive inputs redacted. This gives operators a direct path from a client report (“I saw requestId X”) to the exact server-side failure.

What to log vs what to return

- Return: stable code, safe message, requestId, and minimal safe metadata.

- Log: original error, stack trace, downstream response codes, timing, and resolver path.

- Redact: secrets, tokens, passwords, full credit card numbers, and any regulated personal data not required for debugging.

Testing error behavior as part of the API contract

Error handling is part of your API surface. Add tests that assert codes, paths, and nullability behavior. For example, verify that unauthorized access to a field returns null plus a FORBIDDEN error at the correct path, and that validation failures return BAD_USER_INPUT with field metadata. Also test that unexpected exceptions become INTERNAL with a generic message in production mode.

Step-by-step: a minimal error contract test checklist

- Validation: invalid inputs produce

BAD_USER_INPUTwith field details and no stack trace. - Auth: missing identity produces

UNAUTHENTICATED; insufficient permission producesFORBIDDEN(or your chosen alternative). - Not found: ensure behavior is consistent with your enumeration policy.

- Conflict: concurrent update or uniqueness issues produce

CONFLICT(typed result or error). - Dependency: best-effort fields fail with

DEPENDENCY_FAILEDand do not null out unrelated data. - Internal: unexpected exceptions map to

INTERNALwith a requestId and generic message.