Recognizing the N+1 Problem in GraphQL Resolver Execution

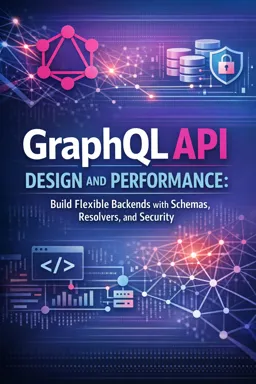

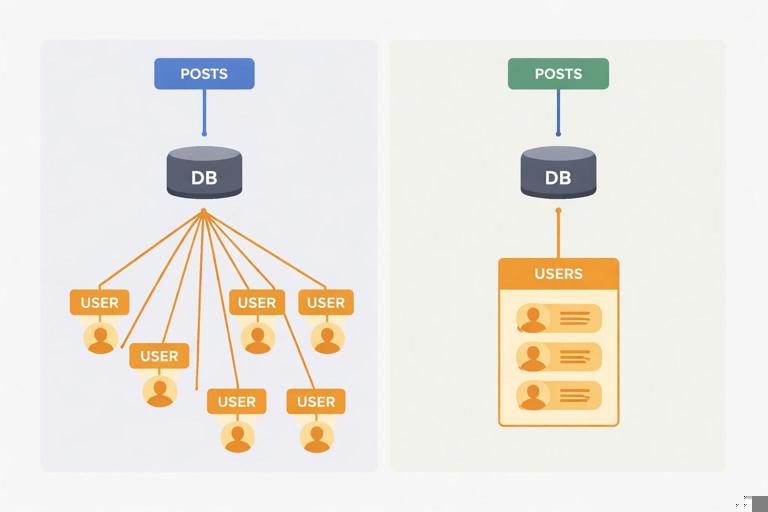

In GraphQL, the N+1 problem appears when a list field triggers additional per-item fetches for a nested field. A typical example is querying a list of posts and, for each post, resolving its author. If the posts list is fetched with one database call (the “1”), and then each post’s author is fetched individually (the “N”), the total becomes 1 + N queries. This often happens because resolvers are written in a straightforward way: the parent resolver returns items, and the child resolver fetches related data for each item. The issue is not GraphQL itself; it is the combination of nested selection sets and naive per-item data access patterns.

The impact is larger than “more queries.” It increases latency (many round trips), amplifies load on databases and downstream services, and makes performance unpredictable because query cost depends on list sizes. Even if each individual query is fast, hundreds of small queries can saturate connection pools, overwhelm caches, and create tail latency spikes. The key observation is that GraphQL executes resolvers per field, and list fields multiply the number of resolver invocations. Eliminating N+1 means changing the data access pattern so that related data is fetched in batches rather than one-by-one.

How to Confirm You Have N+1 (and Where It Comes From)

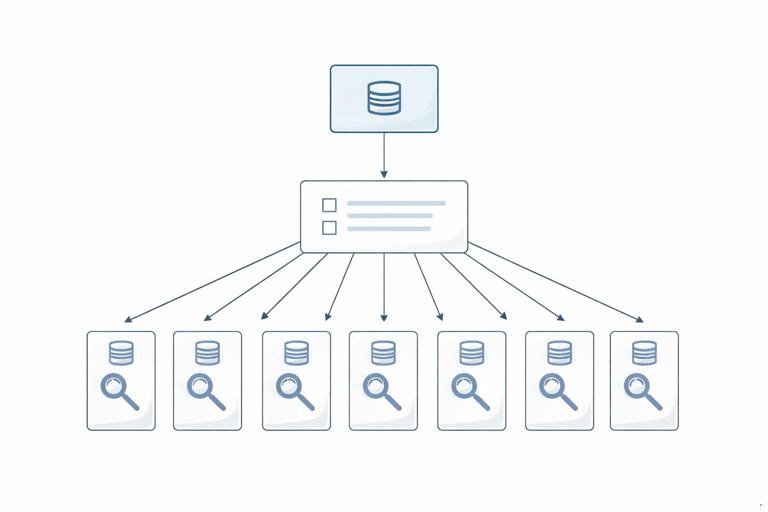

Before fixing N+1, you need to confirm it and identify which field paths cause it. A reliable approach is to instrument your data access layer and log each query with a request identifier. Then run a representative GraphQL query and count how many times a particular data fetch is executed. If you see a repeating pattern like “SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ?” executed dozens of times within one GraphQL request, you likely have N+1 on a nested field such as Post.author.

Another way is to measure resolver call counts and durations per field path. Many GraphQL server frameworks provide hooks or plugins to trace resolver execution. You are looking for a field that is invoked N times (once per list item) and inside it performs I/O. The root cause is usually that the resolver only knows about one parent object at a time, so it fetches related data for that single object. The fix is to introduce a batching layer that can see all requested keys during the request and fetch them together.

Batching as the Core Strategy

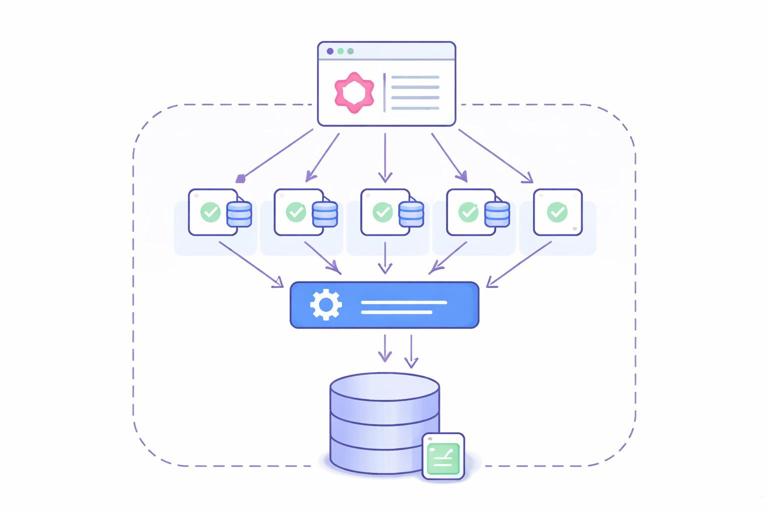

Batching means collecting multiple keys (for example, user IDs) and fetching all corresponding records in one operation (for example, SELECT * FROM users WHERE id IN (...)). In GraphQL, batching is especially effective because many sibling resolvers are executed within the same request and often need the same type of related data. Instead of letting each resolver call the database, you route those calls through a batch function that can combine them.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Batching alone is not enough; you also need to preserve the mapping between requested keys and returned results. If you request authors for posts with IDs [p1, p2, p3], you might batch user IDs [u9, u2, u9]. The batch layer must return results aligned with the input order, including duplicates and missing values. This is where the DataLoader pattern is commonly used: it batches loads and provides per-request caching so repeated keys are not fetched multiple times.

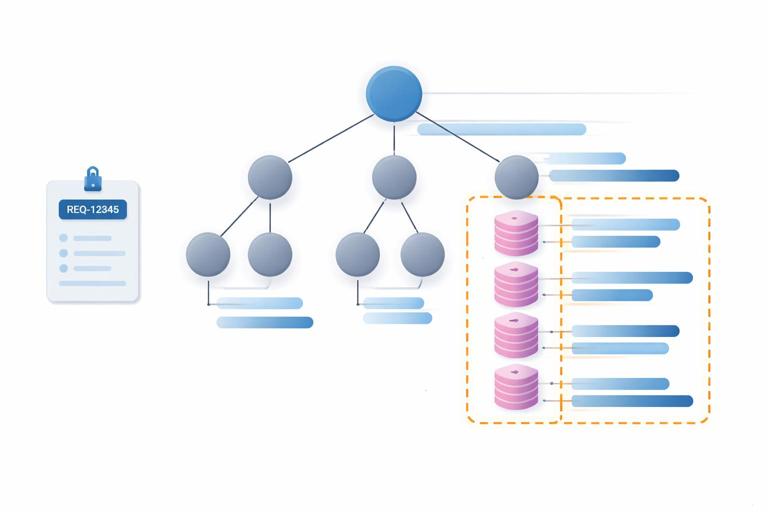

The DataLoader Pattern: What It Guarantees

A DataLoader is a request-scoped utility that provides two main guarantees: (1) it batches multiple load(key) calls that occur within the same event loop tick (or execution window) into a single batch function call, and (2) it caches results per key for the duration of the request. The batch function receives an array of keys and must return an array of results in the same order. If a key cannot be resolved, it returns null or an error placeholder depending on your error strategy.

Request-scoped is crucial. If you share a DataLoader across requests, you risk leaking data between users and serving stale or unauthorized results. Per-request loaders also align with GraphQL’s execution model: each request has its own selection set and its own set of keys to batch. The cache is not meant to replace your application cache; it is a short-lived deduplication mechanism to avoid repeated loads during a single request.

Step-by-Step: Refactoring a Naive Resolver into a DataLoader-Based Resolver

Consider a simplified scenario: you have posts and users. A naive implementation might fetch posts, then for each post fetch the author by ID. The goal is to replace per-post author fetching with a batched load.

Step 1: Identify the key you will batch on

For Post.author, the natural key is authorId. The loader will accept user IDs and return user objects. If your nested field needs something else (for example, “latest comment per post”), the key might be post IDs, or a composite key like {postId, viewerId} depending on authorization and personalization needs.

Step 2: Write the batch function

The batch function takes an array of keys and performs one efficient fetch. For SQL, that is often an IN query. For a REST downstream service, it might be a bulk endpoint. The important part is to return results in the same order as keys.

// Pseudocode (Node-style) for a userById loader batch function async function batchUsersById(userIds) { // 1) Fetch all users in one call const rows = await db.query('SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = ANY($1)', [userIds]); // 2) Index by id for fast lookup const byId = new Map(rows.map(u => [u.id, u])); // 3) Return results aligned with input order return userIds.map(id => byId.get(id) ?? null); }Notice the alignment step. Databases do not guarantee order matching your input keys. If you return rows directly, you will mismatch authors to posts. Always re-order explicitly.

Step 3: Create the loader per request

Attach loaders to the GraphQL context so every resolver can access them. The context is created once per request, making it a natural place to store request-scoped utilities.

// Pseudocode context factory function buildContext({ request }) { return { requestId: request.id, loaders: { userById: new DataLoader(batchUsersById) } }; }If you have multiple data sources, you typically create multiple loaders: userById, postById, commentsByPostId, and so on. Keep them small and focused on one access pattern each.

Step 4: Update the field resolver to use the loader

Instead of calling the database directly, the resolver calls load on the loader. Multiple calls across different posts will be batched automatically.

// Pseudocode resolver Post: { author: (post, args, ctx) => { return ctx.loaders.userById.load(post.authorId); } }Now, if the client requests 50 posts with authors, you should see 1 query for posts and 1 query for users (or a small number of queries depending on batching windows and other fields), rather than 51 queries.

Step 5: Validate batching and caching behavior

Run a query that requests authors for many posts and confirm that the user fetch happens once. Also test duplicates: if multiple posts share the same author, the loader cache should deduplicate within the request, so the author is fetched once and reused.

Batching Beyond Simple Foreign Keys

Not all N+1 cases are “load by ID.” Common patterns include one-to-many relations (comments by post), computed aggregations (like counts), and conditional fetching based on arguments. Each can be batched, but the batch key and return shape differ.

Batching one-to-many: comments by postId

For a field like Post.comments, the loader takes an array of post IDs and returns an array of arrays (comments per post). The batch function fetches all comments for all requested posts, then groups them.

// Pseudocode async function batchCommentsByPostId(postIds) { const rows = await db.query( 'SELECT * FROM comments WHERE post_id = ANY($1) ORDER BY created_at DESC', [postIds] ); const grouped = new Map(); for (const id of postIds) grouped.set(id, []); for (const c of rows) { if (!grouped.has(c.post_id)) grouped.set(c.post_id, []); grouped.get(c.post_id).push(c); } return postIds.map(id => grouped.get(id) ?? []); }This eliminates N+1 where each post would otherwise fetch its comments separately. It also centralizes ordering rules so all resolvers behave consistently.

Batching aggregations: counts and summaries

Fields like Post.commentCount or User.postCount are frequent N+1 offenders because they look “small” but still require I/O. Batch them with a grouped aggregation query.

// Pseudocode async function batchCommentCountsByPostId(postIds) { const rows = await db.query( 'SELECT post_id, COUNT(*) AS cnt FROM comments WHERE post_id = ANY($1) GROUP BY post_id', [postIds] ); const byId = new Map(rows.map(r => [r.post_id, Number(r.cnt)])); return postIds.map(id => byId.get(id) ?? 0); }Batching counts is often one of the highest ROI optimizations because it reduces many small queries into one grouped query.

Handling Arguments and Variants: When One Loader Is Not Enough

A common pitfall is using one loader for a field that accepts arguments that change the result, such as comments(limit: 10, sort: NEWEST). If you cache only by post ID, you might incorrectly reuse results for different argument combinations. The fix is to include arguments in the cache key, or create separate loaders per variant.

For example, if you support comments(limit), you can build a composite key like {postId, limit} and serialize it to a stable string. The batch function then groups keys by limit and runs one query per limit value, or uses a window function to fetch top-N per group depending on your database capabilities.

// Pseudocode composite key loader const commentsByPostAndLimit = new DataLoader(async keys => { // keys: [{postId, limit}, ...] const groups = new Map(); for (const k of keys) { const bucket = groups.get(k.limit) ?? []; bucket.push(k.postId); groups.set(k.limit, bucket); } const resultsByKey = new Map(); for (const [limit, postIds] of groups.entries()) { const rows = await db.query( 'SELECT * FROM comments WHERE post_id = ANY($1) ORDER BY created_at DESC', [postIds] ); // Apply limit per post in memory (simple but may be heavy) const perPost = new Map(postIds.map(id => [id, []])); for (const c of rows) { const arr = perPost.get(c.post_id); if (arr && arr.length < limit) arr.push(c); } for (const id of postIds) { resultsByKey.set(`${id}:${limit}`, perPost.get(id) ?? []); } } return keys.map(k => resultsByKey.get(`${k.postId}:${k.limit}`) ?? []); }, { cacheKeyFn: k => `${k.postId}:${k.limit}` });The example shows the idea, but you should be careful with in-memory limiting for large datasets. In practice, you may prefer database-side “top N per group” queries or precomputed summaries for heavy workloads.

Authorization and Personalization: Keeping Batching Safe

Batching changes how and when data is fetched, which can affect authorization. If a field’s result depends on the viewer (for example, “canViewerEdit” or “viewerHasLiked”), you must ensure the loader’s cache key includes viewer identity or that the loader is request-scoped and only used within one viewer context. Request-scoped loaders usually solve this because each request corresponds to one authenticated viewer, but be cautious with server architectures where one request might represent multiple viewers (rare, but possible in internal tooling).

Another issue is partial visibility. Suppose a user can only see certain records. If your batch query fetches all records for all keys and then filters in memory, you might accidentally leak timing information or return unauthorized objects if filtering is buggy. Prefer enforcing authorization at the data access layer: include tenant constraints, row-level security, or explicit WHERE clauses so unauthorized rows are never returned. Then the loader simply maps missing rows to null.

Preventing Over-Batching and New Bottlenecks

Batching is powerful, but it can create large “IN” queries or huge payloads if you batch too much. Many DataLoader implementations allow configuring a maximum batch size. This can protect your database from extremely large queries and keep response times stable. If your list sizes can be large, set a max batch size and let the loader split into multiple batches.

Also consider the shape of your downstream systems. Some services perform poorly with large bulk requests, or have strict limits. In those cases, you may need to chunk keys, apply concurrency limits, or use a dedicated bulk endpoint. The goal is not “one query always,” but “a small, controlled number of efficient queries.”

Dealing with Nested N+1: Multi-Level Relationships

N+1 can stack across levels: posts → comments → author. Even if you batch authors for posts, you might still have N+1 for comment authors. The DataLoader pattern scales well here because each type of relationship gets its own loader. When resolving comment authors, you reuse the same userById loader, and it will batch user IDs across both post authors and comment authors within the same request.

This is an important benefit: loaders do not just fix one field; they create a shared batching layer across the entire request. If multiple parts of the query need the same entity type, they converge into the same batched fetch.

Cache Semantics: What DataLoader Caches (and What It Should Not)

DataLoader’s cache is a memoization cache for the duration of the request. It prevents duplicate loads for the same key and ensures consistent object identity within a request (helpful if you rely on referential equality in some layers). It is not a cross-request cache and should not be treated as one. If you need cross-request caching, implement it in your data access layer (for example, Redis) and have the batch function consult it.

You also need to consider mutations within the same request. If a mutation updates a user and the same request later resolves that user again, the loader might return a cached stale value. The typical fix is to clear or prime the loader cache after writes. Many DataLoader libraries support clear(key) and prime(key, value). Use these in mutation resolvers or in a shared write service.

// Pseudocode after updating a user const updated = await userService.updateUser(id, patch); ctx.loaders.userById.clear(id).prime(id, updated); return updated;This keeps subsequent reads in the same request consistent with the write.

Practical Checklist for Rolling Out DataLoader Safely

When introducing batching, treat it as a performance refactor with correctness risks. A structured rollout helps avoid subtle bugs.

- Start with one high-impact field path (for example,

Post.authororPost.commentCount) and add a loader for it. - Add instrumentation to the batch function: number of keys, unique keys, batch duration, and downstream query count.

- Verify ordering and missing-key behavior by testing keys that do not exist and duplicate keys.

- Confirm request scoping: loaders must be created per request and stored on context, not in global singletons.

- Validate authorization constraints inside the batch query, not only in resolver code.

- Set a max batch size if list sizes can be large, and test worst-case queries.

- Handle mutations by clearing or priming loader caches for affected keys.

When Batching Is Not the Best Tool

Some N+1-like symptoms are better solved with different techniques. If a nested field always needs to be returned with the parent and the relationship is stable, a join-based fetch in the parent resolver (or a single optimized query) might be simpler and faster than DataLoader. Similarly, if you need complex filtering across relationships, pushing the work into a single database query can outperform batching multiple simpler queries.

DataLoader is most effective when you have many small lookups by key scattered across the resolver tree. For cases where you can predict the full data shape upfront, consider fetching a richer parent payload and mapping it to GraphQL fields without additional I/O. In practice, many production systems use both: joins for predictable relationships and loaders for opportunistic batching across the request.