Why caching in GraphQL is different

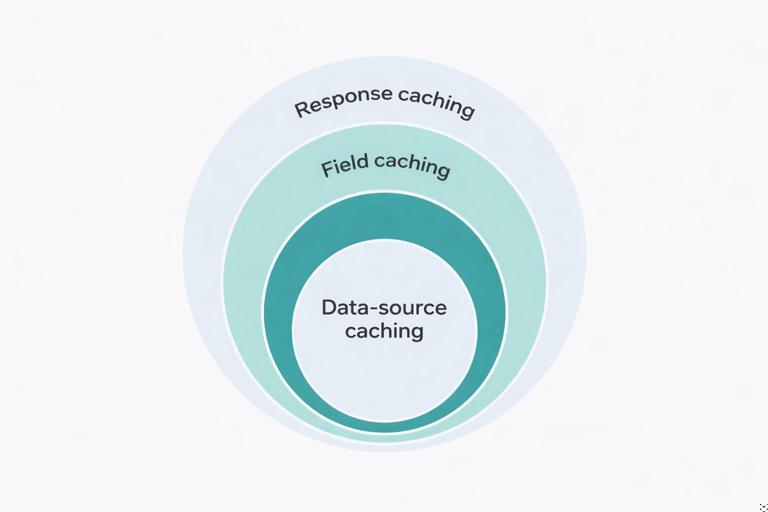

GraphQL caching is trickier than REST caching because the “resource” is not a single URL that always returns the same shape. A single endpoint can return many different selections, arguments, and nested expansions. That means you must decide what you are caching: the entire operation result (response caching), a subset of the result (field caching), or the underlying fetches to databases and services (data-source caching). Each layer has different correctness risks, invalidation strategies, and performance payoffs.

A practical mental model is to treat caching as a set of concentric rings. The outer ring (response caching) can eliminate most work when the same operation repeats. The middle ring (field caching) targets expensive subtrees that appear across many operations. The inner ring (data-source caching) reduces repeated calls to the same backend systems even when the GraphQL selection changes. You can use one layer, but most production systems combine them carefully.

Layer 1: Response caching (operation-level caching)

What it is and when it works

Response caching stores the full JSON result of a GraphQL operation (query only, not mutation) keyed by the operation identity and variables, and often by user context. If the same query document and variables are requested again, the server can return the cached JSON without executing resolvers. This is the highest leverage layer because it can skip parsing, validation, authorization checks (sometimes), resolver execution, and downstream calls.

Response caching works best for: public or semi-public data, high read repetition, stable results for short windows, and queries that are expensive to compute. It is less effective when every request is unique (highly variable filters), when results are personalized per user, or when authorization depends on dynamic conditions that must be re-evaluated each time.

Key design decisions

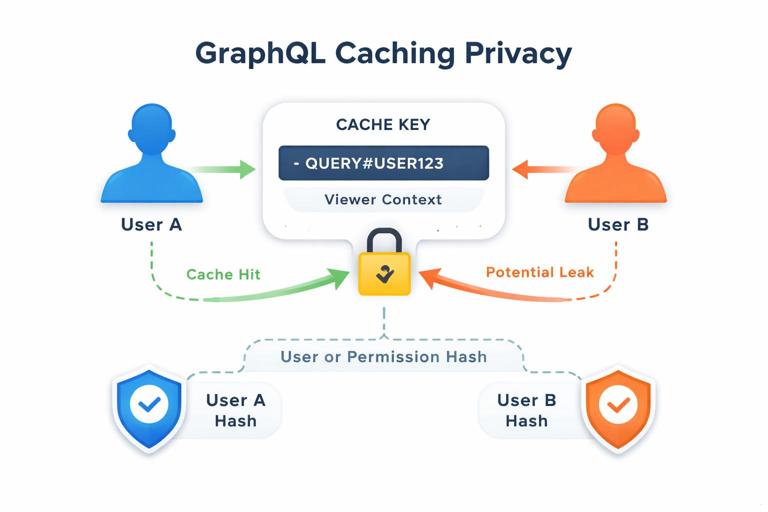

Cache key composition is the core of correctness. A typical key includes: a normalized operation identifier (persisted query ID or a hash of the query document), variables (canonical JSON), and a representation of the requester context that affects the result (user ID, roles, tenant ID, locale, feature flags). If you omit a context dimension that changes the output, you risk leaking data across users.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

TTL vs invalidation: response caches are commonly TTL-based because invalidating every affected operation on writes is complex. TTLs can be short (seconds) for frequently changing data, or longer for stable data. If you need stronger freshness, you can add targeted invalidation using tags (explained below) or by coupling invalidation to domain events.

Partial caching: some platforms support “stale-while-revalidate” where you serve a slightly stale response quickly and refresh in the background. This can smooth latency spikes for expensive queries.

Step-by-step: implement response caching with persisted queries

Step 1: Adopt persisted queries or operation hashing. Persisted queries give you a stable identifier and reduce cache fragmentation caused by semantically identical but textually different queries (whitespace, field order). If you cannot persist, hash the normalized query string after parsing and printing it in a canonical form.

Step 2: Define a cache key schema. A practical key format is: gql:resp:{opId}:{varsHash}:{viewerKey}. The viewerKey should include tenant and authorization-relevant attributes. Keep it compact; store the full context separately if needed.

Step 3: Decide cacheability rules. Only cache queries, not mutations. Consider disallowing caching when the request includes directives like @skip/@include with variable conditions unless those variables are part of the key (they should be). Also decide whether to cache when errors occur; many teams cache only successful responses to avoid persisting transient failures.

Step 4: Add TTL and optional tags. TTL is mandatory. Tags are optional metadata that let you invalidate by entity or domain concept (for example, User:123, Product:55). Tags require you to compute which entities were involved in the response, which can be done by instrumentation in resolvers or by analyzing returned IDs.

Step 5: Implement read-through caching in the request pipeline. On request start, compute the key, check cache, and if present return immediately. On miss, execute the operation and store the JSON result with TTL (and tags if used).

// Pseudocode (framework-agnostic) for response caching middleware

async function executeGraphQLWithResponseCache({ opId, query, variables, context }) {

if (context.operationType !== 'query') {

return executeGraphQL({ query, variables, context });

}

const viewerKey = `${context.tenantId}:${context.userId || 'anon'}:${context.roleVersion}`;

const varsHash = stableHash(variables);

const cacheKey = `gql:resp:${opId}:${varsHash}:${viewerKey}`;

const cached = await cache.get(cacheKey);

if (cached) return JSON.parse(cached);

const result = await executeGraphQL({ query, variables, context });

if (!result.errors || result.errors.length === 0) {

const ttlSeconds = 15; // example

await cache.set(cacheKey, JSON.stringify(result), ttlSeconds);

}

return result;

}Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

Authorization drift: if permissions can change while a cached response is still valid, you can leak data. Mitigate by including a permission version in the key (for example, a role assignment version or policy revision) or by using short TTLs for sensitive data.

Cache fragmentation: if clients send many unique queries, response caching yields low hit rates. Persisted queries, query whitelisting, and client query normalization help. Another tactic is to encourage clients to reuse operation documents and vary only variables.

Over-caching large responses: caching huge JSON blobs can increase memory and network costs. Use size limits, compress values, and prefer field/data-source caching for very large payloads.

Layer 2: Field caching (subtree caching)

What it is and why it helps

Field caching stores the result of a specific field resolver (or a subtree rooted at that field) so that repeated executions across different operations can reuse it. Unlike response caching, field caching can still help when the overall query differs, as long as the same expensive field appears with the same arguments and parent identity.

Field caching is especially useful for expensive computed fields (for example, a recommendation list, a pricing calculation, a permissions matrix, or a markdown-to-HTML transformation) and for fields that aggregate multiple sources. It is also a way to reduce load when response caching is not feasible due to personalization at the top level but some nested fields are shared.

What must be in the cache key

A field cache key must include: the parent object identity (for example, Product:55), the field name, field arguments, and any context that changes the field output (currency, locale, viewer segment). If the field result depends on sibling selections (rare but possible when resolvers inspect the selection set), you must include a representation of the selection in the key or avoid caching that field.

Also consider whether the field is nullable and whether “not found” should be cached. Caching nulls can be beneficial to prevent repeated expensive misses, but it can also delay visibility of newly created data. Use short TTLs for negative caching.

Step-by-step: add field caching to a resolver

Step 1: Identify candidate fields. Use tracing to find resolvers with high latency or high call counts. Prefer fields that are pure functions of (parent, args, context) and do not have side effects.

Step 2: Define invalidation strategy. For many fields, TTL is enough. For fields tied to specific entities, tag-based invalidation (by entity ID) is often manageable.

Step 3: Implement a cache wrapper around the resolver. The wrapper computes a key, checks cache, and on miss computes and stores the value.

// Example: caching Product.priceSummary(currency)

async function priceSummaryResolver(product, args, context) {

const parentKey = `Product:${product.id}`;

const viewerKey = `${context.tenantId}:${context.userId || 'anon'}`;

const key = `gql:field:${parentKey}:priceSummary:${args.currency}:${viewerKey}`;

const cached = await cache.get(key);

if (cached) return JSON.parse(cached);

const value = await pricingService.computeSummary({

productId: product.id,

currency: args.currency,

viewerId: context.userId

});

await cache.set(key, JSON.stringify(value), 30); // 30s TTL

return value;

}Step 4: Ensure consistent serialization. Store JSON with stable ordering if you hash it later, and keep payloads small. If values are large, consider compressing or caching only identifiers and recomputing presentation fields.

Step 5: Add observability. Track hit rate per field, average compute time saved, and stale reads. Field caching can silently become ineffective if keys include too much context or if TTL is too short.

Advanced technique: entity tags and targeted invalidation

To invalidate field caches when an entity changes, attach tags like Product:55 to cache entries. When a product is updated, publish an event that triggers invalidation of all keys tagged with that product. Implementation options include: maintaining a tag-to-keys index (more write overhead), using cache systems that support native tagging, or using a versioned key approach (store Product:55:version and include it in keys so bumping the version invalidates all derived keys).

// Versioned key approach

// Read product version from cache (or DB) and include it in the field key

const version = await cache.get(`ver:Product:${product.id}`) || '0';

const key = `gql:field:Product:${product.id}:v${version}:priceSummary:${args.currency}`;

// On product update

await cache.incr(`ver:Product:${product.id}`);This approach avoids storing lists of keys per tag and works well when you can tolerate eventual consistency between the update and the next read.

Layer 3: Data-source caching (backend call caching)

What it is and how it differs from batching

Data-source caching stores the results of calls to underlying systems: database queries, HTTP calls to microservices, or expensive computations. It sits below GraphQL and can be shared across multiple fields and operations. While batching reduces the number of calls within a single request, data-source caching reduces calls across requests and across time windows.

Data-source caching is often the safest caching layer because it is closer to the source of truth and can be aligned with domain entities and service semantics. It also avoids the complexity of caching GraphQL-shaped JSON, which can vary widely by selection set.

Where to implement it

You can implement data-source caching in three common places: (1) inside a service client (HTTP/GRPC wrapper), (2) inside a repository/DAO layer (for database reads), or (3) in a dedicated “data source” abstraction used by resolvers. The best location is where you can standardize keys, TTLs, and invalidation without duplicating logic across resolvers.

Step-by-step: cache an HTTP service call

Step 1: Choose cache scope. Some caches are per-request (in-memory map) to avoid duplicate calls within the same request; others are shared (Redis/Memcached) to reuse across requests. For cross-request caching, use a shared cache.

Step 2: Define a stable key. Include endpoint name, parameters, and tenant. Avoid including volatile headers unless they change the response. If the service response depends on authorization, include a viewer or permission dimension.

Step 3: Implement read-through caching with TTL and circuit breakers. If the downstream service is slow, caching can help, but you also need timeouts and fallbacks. Consider serving stale cached data when the service is down if your product allows it.

// Example: caching a user profile fetch from a downstream service

async function getUserProfile({ tenantId, userId }) {

const key = `svc:userProfile:${tenantId}:${userId}`;

const cached = await cache.get(key);

if (cached) return JSON.parse(cached);

const profile = await http.get(`/tenants/${tenantId}/users/${userId}/profile`, {

timeoutMs: 500

});

await cache.set(key, JSON.stringify(profile), 60); // 60s TTL

return profile;

}Step 4: Invalidate or shorten TTL on writes. If your system updates profiles, invalidate the key when updates occur. If updates happen outside your system, prefer short TTLs or event-driven invalidation if you can subscribe to change events.

Database-level caching considerations

For databases, caching can be done at multiple levels: query result caching, entity caching, or materialized views. In GraphQL backends, entity caching (by primary key) is often the most predictable: cache User:123 or Product:55 reads for a short TTL. Query caching (for example, caching “top products” lists) can be effective but requires careful keying for filters and sorting and a clear invalidation story.

Be cautious with caching database query results that depend on transaction isolation or rapidly changing counters. If you cache such results, define acceptable staleness and document it for client expectations.

Choosing the right layer (and combining them)

A practical decision checklist

Use response caching when the same operation repeats frequently and the output is safe to share within a defined viewer scope. Use field caching when only parts of the graph are expensive and reused across different operations. Use data-source caching when you want broad reuse across the schema and you can define stable keys aligned with domain entities or service calls.

- If you have high query diversity: prefer data-source caching and selective field caching.

- If you have a small set of popular queries: response caching can deliver the biggest wins.

- If correctness is paramount and invalidation is hard: use short TTLs, versioned keys, and avoid caching highly sensitive fields.

Cache control and per-field TTL policies

Many GraphQL servers implement a cache policy system where each field can declare a TTL or “scope” (public vs private). The effective TTL of a response can be computed as the minimum TTL across all fields included. This prevents caching a response longer than its most volatile component. Even if you do not implement full cache control directives, you can emulate this by collecting TTL hints during resolver execution and using them to set the response cache TTL.

// Pseudocode: collecting TTL hints

context.cacheHints = [];

function setCacheHint(ttlSeconds, scope) {

context.cacheHints.push({ ttlSeconds, scope });

}

// In a resolver

setCacheHint(10, 'PRIVATE');

// After execution

const ttl = Math.min(...context.cacheHints.map(h => h.ttlSeconds));Correctness and security constraints

Preventing cross-user data leaks

Any cache that can be shared across requests must be evaluated for privacy. Response caching is the riskiest because it stores fully assembled results that may include user-specific fields. Field caching can also leak if the key omits viewer context for fields like isViewerFollowing or canEdit. Data-source caching can leak if you cache an authorization-filtered list without including the permission scope in the key.

A safe default is: treat caches as “private” unless you can prove the data is public. For private caches, include user identity (or a permission hash) in the key. For public caches, ensure the resolver never returns private data for any viewer.

Handling mutations and cache invalidation

Mutations change data and therefore must trigger invalidation. A practical approach is to invalidate at the data-source and field layers using entity versions or tags, and rely on short TTLs for response caches. If you do implement response cache invalidation, do it via tags derived from entities touched by the mutation (for example, updating a product invalidates responses tagged with Product:55).

Also consider write-after-read hazards: a client may perform a mutation and then immediately query. If your caches are eventually consistent, you may serve stale data. Mitigations include: bypass caches for a short window after a mutation for that user, or bump entity versions synchronously as part of the mutation flow.

Operational practices: making caching measurable and safe

Metrics to track

Track cache hit rate, miss rate, and eviction rate per layer. For response caching, track hit rate per operation ID. For field caching, track hit rate per field name and argument patterns. For data-source caching, track hit rate per downstream endpoint or query type. Also track p95 latency with and without cache hits to quantify benefit.

Debuggability and cache transparency

Add response headers or extensions in the GraphQL response (for internal clients) to indicate whether a request was served from cache and which layer. For example, include an extension like extensions.cache = { response: 'HIT', fields: ['Product.priceSummary:MISS'] }. This makes it easier to tune TTLs and keys without guessing.

Protecting caches from abuse

Caches can be attacked by forcing high cardinality keys (cache busting) or by requesting huge responses that fill memory. Mitigate with query cost limits, maximum response size, and cache admission policies (for example, do not cache responses above a size threshold, and do not cache operations with extremely high variable cardinality). For shared caches, set per-tenant quotas and consider segregating keys by tenant prefix to simplify monitoring and eviction.