What “deployment and operations” means for a GraphQL service

Deployment and operations covers everything that happens after your GraphQL server code is written and tested: building artifacts, promoting them through environments, configuring runtime behavior safely, and operating the service reliably under real traffic. For GraphQL specifically, operations must account for schema changes, client compatibility, and traffic patterns that can shift quickly (for example, a new client query can create a new hot path). This chapter focuses on CI/CD pipelines, configuration and secrets, and environment management patterns that keep releases repeatable and safe.

CI/CD pipeline goals and release strategy

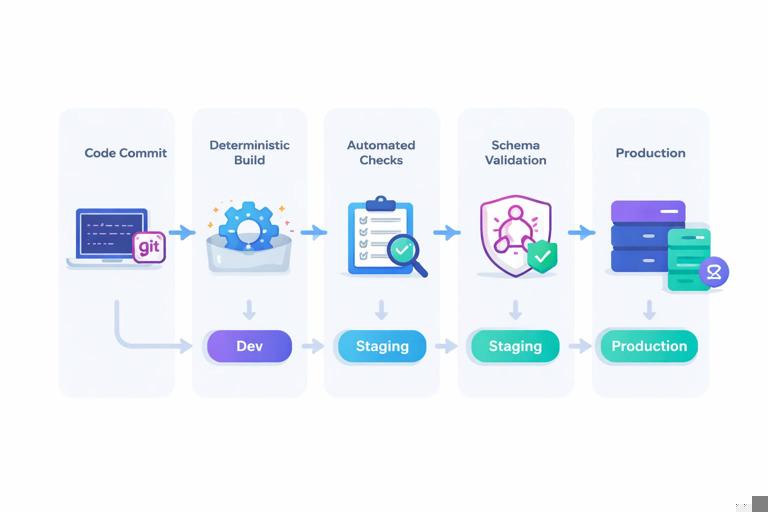

A CI/CD pipeline should produce the same result every time from the same inputs. For a GraphQL server, that means: deterministic builds (lockfiles, pinned base images), automated checks (lint, typecheck, tests), and controlled promotion (dev → staging → production). A good pipeline also treats the schema as a deployable artifact: it validates that the schema can be served, that it matches expectations for the environment, and that it can be rolled out without surprising clients.

Choose a deployment model: rolling, blue/green, or canary

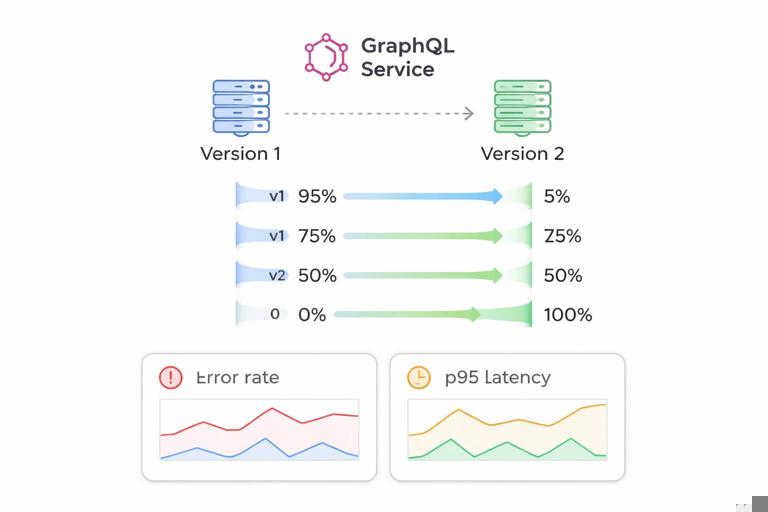

Most GraphQL services can use standard web deployment strategies, but you should align the strategy with your risk tolerance and traffic profile. Rolling deployments gradually replace instances; they are simple but can temporarily run mixed versions. Blue/green keeps two full stacks and switches traffic, which is safer for quick rollback but costs more. Canary sends a small percentage of traffic to the new version first, which is excellent for catching production-only issues (like a slow resolver path) before full rollout.

Define “release units” for GraphQL

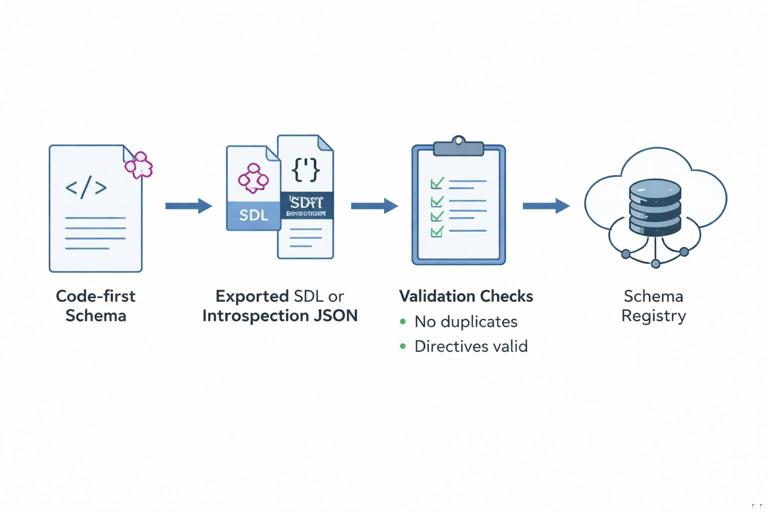

Decide what constitutes a release: server code only, server code plus schema, and potentially related configuration. In practice, treat these as separate but coordinated units: (1) application artifact (container image), (2) schema artifact (SDL or introspection JSON), and (3) configuration bundle (environment variables, feature flags). Keeping these explicit helps you reason about what changed when an incident occurs.

Step-by-step: a practical CI pipeline for a GraphQL server

The following steps are tool-agnostic and can be implemented in GitHub Actions, GitLab CI, Jenkins, CircleCI, or similar systems. The key is the order and the gates.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Step 1: deterministic install and build

Use a lockfile and fail the build if the lockfile is out of date. Build artifacts in a clean environment (CI runner or container). If you use Node.js, pin the Node version; if you use JVM or Go, pin toolchains similarly. This prevents “works on my machine” drift.

# Example (Node.js) build steps in CI (conceptual) node --version npm ci npm run lint npm run typecheck npm test npm run buildStep 2: schema artifact generation and validation

Generate the schema artifact as part of CI. Depending on your stack, this might be an SDL file produced from code-first definitions or a printed schema from your server. Validate that the schema can be loaded and that it meets basic invariants (for example, no duplicate type names, no missing scalars, no invalid directives). If you maintain a schema registry, publish the artifact to it from CI.

# Example: export schema (pseudo-command) npm run graphql:schema:export # Validate schema loads and is printable npm run graphql:schema:validateStep 3: compatibility checks against the previous schema

Even if you are not repeating schema design topics here, operationally you still need an automated gate that detects breaking changes before deployment. In CI, compare the new schema artifact to the currently deployed schema (or the latest schema in your registry). Fail the pipeline if the change violates your compatibility policy, or require an explicit override with a change request.

# Example: schema diff gate (conceptual) graphql-schema-diff --old registry:prod --new ./schema.graphql --fail-on-breakingStep 4: build and scan the deployable artifact

Build a container image (or other artifact) and scan it for known vulnerabilities. Also ensure the image is minimal and reproducible (multi-stage builds, pinned base image digests). Store the image in a registry with immutable tags (for example, commit SHA) and optionally a human tag (like “staging”).

# Example container build steps (conceptual) docker build -t registry.example.com/graphql-api:${GIT_SHA} . docker push registry.example.com/graphql-api:${GIT_SHA} trivy image registry.example.com/graphql-api:${GIT_SHA}Step 5: ephemeral environment smoke test

Before touching shared staging, spin up an ephemeral environment (a temporary namespace or preview environment) and run smoke tests: server starts, health endpoints respond, and a small set of representative GraphQL operations succeed. This catches missing environment variables, migrations not applied, or misconfigured network policies.

- Deploy to a temporary namespace with the new image.

- Run a readiness check (HTTP 200 on /healthz or equivalent).

- Run a small GraphQL smoke suite (a few queries/mutations) against the temporary endpoint.

- Tear down the namespace after success/failure.

CD: promotion through environments with safe rollouts

Continuous delivery is about promoting the same artifact through environments by changing only configuration and traffic routing. The most common operational mistake is rebuilding for each environment, which makes “staging passed” less meaningful. Instead, build once, then promote the same image digest from dev to staging to production.

Environment promotion checklist

- Artifact immutability: promote by digest or commit SHA, not “latest”.

- Config separation: environment-specific values injected at deploy time.

- Automated gates: require health checks and smoke tests after deploy.

- Progressive delivery: canary or rolling with measured error/latency budgets.

- Fast rollback: ability to revert traffic to the previous version quickly.

Step-by-step: canary rollout for a GraphQL server

A canary rollout reduces risk by exposing a small fraction of traffic to the new version. The key is to measure the right signals during the canary window: error rate, latency (especially p95/p99), and resource usage. For GraphQL, also watch for spikes in resolver time or downstream dependency errors.

- Deploy new version alongside old version (two replica sets).

- Route 1–5% of traffic to the new version (via service mesh, ingress controller, or load balancer rules).

- Monitor key SLO signals for a fixed window (for example, 10–30 minutes): HTTP 5xx, GraphQL error rate, p95 latency, CPU/memory, and downstream timeouts.

- If signals are healthy, increase to 25%, then 50%, then 100%.

- If signals degrade, shift traffic back to the old version and keep the new version for debugging.

Configuration management: separating code from runtime behavior

Configuration is everything that changes between environments or over time without changing code: database URLs, API keys, feature flags, timeouts, and operational toggles. A GraphQL server typically has more configuration than a simple REST service because it coordinates multiple downstream systems and may have multiple operational modes (for example, enabling persisted queries enforcement, toggling introspection, or adjusting query limits).

Principles for safe configuration

- Explicitness: every config value has a name, type, and default policy (required vs optional).

- Validation at startup: fail fast if required config is missing or malformed.

- Least privilege: credentials scoped to the environment and service identity.

- Rotation-friendly: secrets can be rotated without redeploy when possible.

- Auditability: changes to config are tracked (GitOps or config change logs).

Step-by-step: implement config validation at startup

Use a schema validation library (or your language’s type system) to validate environment variables at process start. This prevents partial deployments where some pods crash-loop due to missing values. Also normalize values (for example, parse integers and durations) so the rest of the code uses typed config.

// Example (TypeScript) using a validation approach (conceptual) const Config = { NODE_ENV: oneOf(['development','staging','production']), PORT: int({ default: 4000 }), DATABASE_URL: url({ required: true }), REDIS_URL: url({ required: false }), REQUEST_TIMEOUT_MS: int({ default: 5000 }), ENABLE_INTROSPECTION: bool({ default: false }), LOG_LEVEL: oneOf(['debug','info','warn','error'], { default: 'info' }) }; export const config = validateEnv(process.env, Config);Secrets management: handling credentials without leaking them

Secrets include database passwords, signing keys, third-party API tokens, and encryption keys. The operational goal is to avoid storing secrets in source control, avoid printing them in logs, and minimize the blast radius if a secret is compromised. Use a dedicated secrets manager (cloud provider secret store, Vault, or Kubernetes secrets with encryption at rest) and inject secrets at runtime.

Common injection patterns

- Environment variables injected from a secrets manager (simple, widely supported).

- Mounted files (useful for certificates and key material; supports rotation by updating the file).

- Workload identity (preferred when available): the service authenticates to dependencies without long-lived static secrets.

Rotation and dual-read strategy

For secrets that cannot be rotated instantly (for example, a database password used by multiple services), plan for a transition period where both old and new credentials are valid. Operationally, this means your config loader may support two values (PRIMARY and SECONDARY) and your connection logic tries primary first, then secondary. After all services are updated, remove the old credential.

Environment management: dev, staging, production, and preview

Environment management is about ensuring each environment has a clear purpose and consistent shape. The closer staging is to production, the more meaningful it is as a safety gate. For GraphQL, environment differences can hide issues: a staging environment with smaller datasets might not reveal slow queries; a staging environment without real third-party integrations might not reveal timeout behavior.

Recommended environment roles

- Development: fast iteration, local dependencies, permissive settings.

- Preview environments: per-branch or per-PR deployments for integration checks.

- Staging: production-like infrastructure and configuration, used for release candidates.

- Production: real traffic, strict security and operational controls.

Keep “shape” consistent across environments

Try to keep the same topology: same number of hops (load balancer → gateway → GraphQL), same network policies, same TLS termination approach, and similar autoscaling rules. Differences should be intentional and documented (for example, smaller instance sizes in staging), not accidental.

Runtime toggles: feature flags and operational flags

Feature flags let you change behavior without redeploying. For GraphQL operations, flags are especially useful for controlling high-risk changes: enabling a new downstream integration, switching a caching strategy, or tightening enforcement of operational controls. Operational flags should be designed to be safe under partial rollout (some instances have the flag on, others off) and should be observable (you can see which flag state served a request).

Step-by-step: safe flag rollout

- Introduce the flag defaulting to “off” in all environments.

- Deploy the code with the flag present but disabled.

- Enable the flag in staging and run targeted smoke tests.

- Enable in production for a small cohort (by percentage, tenant, or header-based routing).

- Gradually expand while monitoring latency and error rate.

- Keep a fast “kill switch” path to disable the flag immediately.

Operational endpoints and health checks

Deployments rely on health checks to know when an instance is ready to receive traffic and when it should be restarted. For GraphQL servers, separate concerns: liveness (process is running), readiness (can serve requests), and startup (initialization still happening). Readiness should include checks for critical dependencies only if failing them should remove the instance from traffic; otherwise, you risk cascading failures during partial outages.

Practical health check design

Startup check: returns unhealthy until schema is loaded, config validated, and server is listening.

Liveness check: returns healthy if the event loop is responsive and the process is not wedged.

Readiness check: returns healthy if the server can accept requests; optionally include a lightweight dependency check (like a ping to Redis) if it is strictly required.

Database migrations and deploy coordination

Even though data modeling is covered elsewhere, operations must coordinate schema deployments with database migrations. The key operational rule is to make deployments tolerant of mixed versions during rolling or canary releases. That implies running migrations in a way that does not break the old version while the new version is rolling out.

Step-by-step: migration workflow in CI/CD

- Generate migration scripts as part of development and review them in code review.

- In CD, apply migrations before shifting traffic to the new version when the migration is backward-compatible.

- If a migration is risky or long-running, run it as a separate job with explicit approval and monitoring.

- After full rollout, optionally run cleanup migrations (for example, dropping old columns) in a later release window.

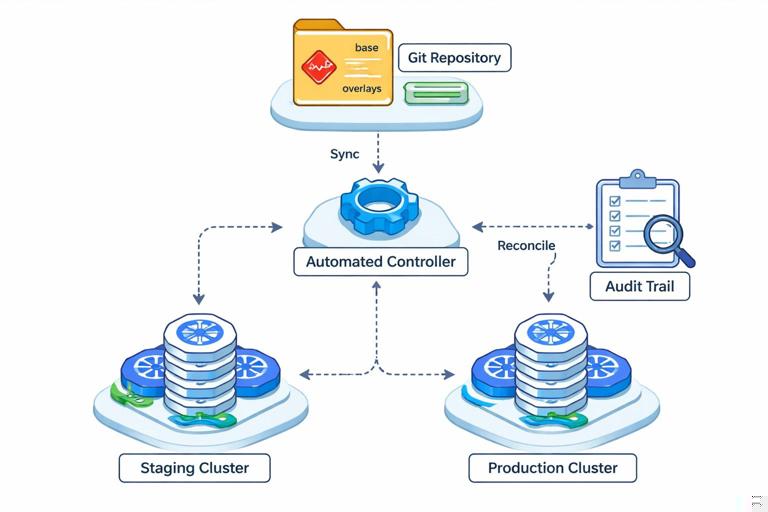

Infrastructure as Code and GitOps for repeatability

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) defines your runtime environment (networks, clusters, load balancers, secrets policies) in version-controlled code. GitOps extends this by making Git the source of truth for deployments: changes are applied by automated controllers, and the deployed state is continuously reconciled to match the repository. For GraphQL services, this improves auditability and reduces configuration drift across environments.

Practical GitOps repository layout

- apps/graphql-api/base: shared deployment manifests (service, deployment, HPA).

- apps/graphql-api/overlays/staging: staging-specific config (replicas, resources).

- apps/graphql-api/overlays/prod: production-specific config (autoscaling thresholds, stricter policies).

- infra/: cluster and network definitions (Terraform/Pulumi/etc.).

Operational safeguards during deploys

Deployments can fail in ways that are not caught by tests: misconfigured environment variables, missing permissions, unexpected traffic spikes, or dependency degradation. Add safeguards that reduce blast radius and speed recovery.

Recommended safeguards

- Resource requests/limits: prevent noisy-neighbor issues and OOM storms.

- Autoscaling: scale on CPU and, if available, request rate or latency signals.

- Timeouts and retries: set conservative server timeouts and align them with upstream load balancer timeouts.

- Circuit breakers/bulkheads: isolate downstream dependencies so one failing system does not take down the entire GraphQL service.

- Deploy freeze windows: restrict production deploys during known high-traffic periods.

Runbooks and on-call readiness for GraphQL deployments

Operational excellence requires documentation that is actionable under pressure. A runbook should map symptoms to checks and mitigations. For GraphQL, include query-related symptoms (latency spikes, increased error rates) and deployment-related symptoms (crash loops, readiness failures, increased memory usage after rollout). Keep runbooks close to the code and update them when incidents occur.

Runbook sections to include

- How to identify the currently deployed version (image digest, commit SHA).

- How to roll back (traffic switch, previous deployment reference).

- Where to check health (dashboards, logs, traces) and which metrics matter during deploys.

- Common failure modes: missing config, secret permission errors, dependency timeouts, CPU throttling.

- Emergency toggles: which feature flags or operational flags can reduce load quickly.

Putting it together: an end-to-end release flow

An end-to-end operational flow ties CI, CD, configuration, and environment management into a single repeatable process. The goal is that every change follows the same path, with automated checks and clear human approvals only where necessary.

Step-by-step: reference release flow

- Developer opens a PR; CI runs build, tests, schema export, schema compatibility gate, and image build.

- CI deploys to a preview environment; smoke tests run against the preview endpoint.

- After merge, CD promotes the same image to staging with staging config; smoke tests and a short canary window run.

- CD promotes the same image to production using canary or blue/green; monitors error rate and latency gates.

- If issues occur, rollback by shifting traffic back and keeping artifacts for debugging; if stable, proceed to full rollout.