Authorization Goals and Threat Model in GraphQL

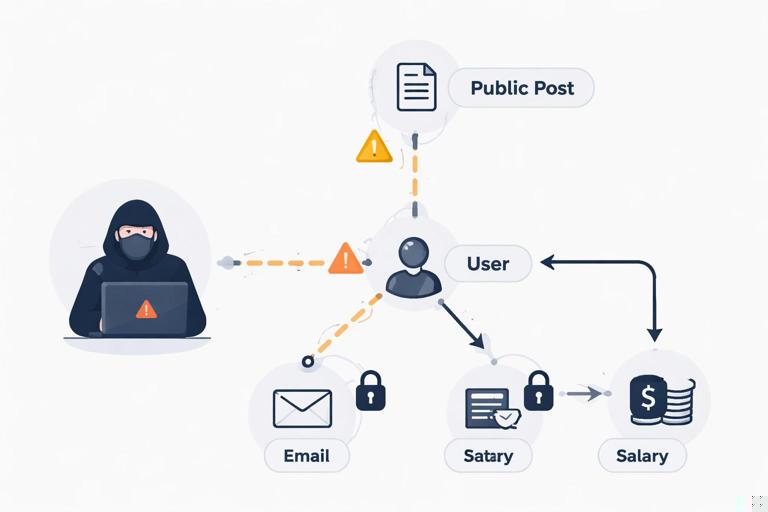

Authorization answers “is this authenticated caller allowed to do this specific thing with this specific data?” In GraphQL, that question appears at multiple levels: operation (can the caller run this mutation?), object (can they see this record?), and field (can they see this attribute?). A common pitfall is assuming that hiding a field from the schema or relying on client behavior is enough. In practice, clients can request any field that exists in the schema, and attackers can craft operations that traverse relationships to reach sensitive data. Good authorization design therefore focuses on: consistent policy definitions, enforcement close to the data, least privilege by default, and predictable failure behavior (deny-by-default, no data leakage through errors).

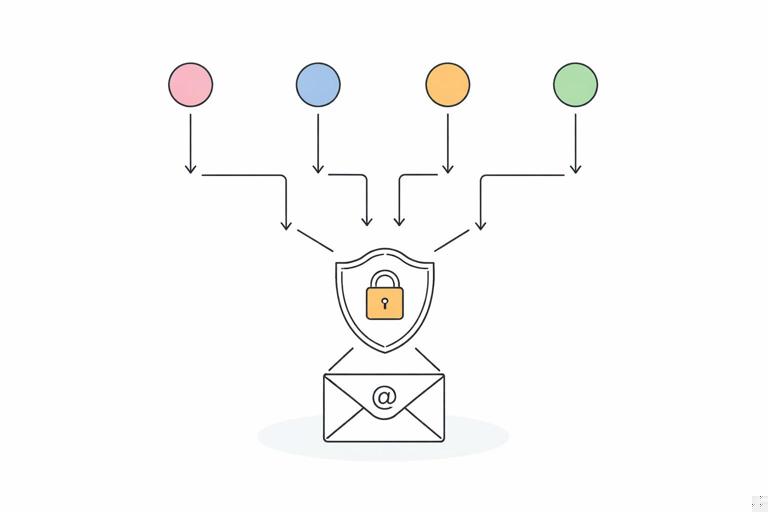

GraphQL’s flexibility also means the same data can be reached through multiple paths. For example, an email address might be accessible via viewer { email }, user(id) { email }, or nested under organization { members { email } }. Authorization must be path-independent: the policy should be enforced wherever the field is resolved, not only in one “main” query. This chapter focuses on role-based access control (RBAC) and field-level permissions, and how to combine them with ownership and contextual checks without duplicating logic across resolvers.

RBAC vs Field-Level Permissions (and Why You Usually Need Both)

RBAC assigns permissions based on roles such as ADMIN, SUPPORT, EDITOR, or USER. It is easy to reason about and works well for coarse-grained access: “admins can manage users,” “support can view billing,” “users can edit their own profile.” Field-level permissions are finer-grained rules that decide whether a specific field is visible or writable. This is essential when a type mixes public and sensitive attributes (for example, User includes email, phone, lastLoginAt, mfaEnabled, salaryBand, etc.).

In GraphQL, field-level permissions are not just “nice to have.” They prevent accidental overexposure when new fields are added. If your default is “allow,” a newly introduced field might become visible to everyone until you remember to add checks. A safer posture is deny-by-default for sensitive fields, and explicit allow rules for roles or conditions. RBAC can decide broad capabilities, while field-level permissions can enforce “only admins can see lastLoginAt” or “only the user themselves can see email.”

Designing a Permission Model: Roles, Scopes, and Actions

Start by defining what you authorize. A practical approach is to model permissions as actions on resources, then map roles to those permissions. Even if you keep “roles” in your identity system, internally you can translate roles into a set of capabilities. For example: user:read, user:write, user:read:sensitive, billing:read, org:manage. This avoids hard-coding role names throughout resolvers and makes it easier to add a new role later.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

For GraphQL, define permissions at three layers: operation-level (queries/mutations), type-level (object access), and field-level (attribute access). Operation-level checks can block entire mutations like deleteUser. Type-level checks ensure the caller can access a specific object instance (e.g., only members of an organization can access that organization). Field-level checks handle sensitive attributes and can also enforce write restrictions (e.g., only admins can set role on a user).

Step-by-step: Build a permission vocabulary

- List sensitive domains: identity, billing, admin controls, audit logs, internal notes.

- For each domain, list actions: read, write, delete, manage, impersonate, export.

- Decide which actions are global (admin-only) vs contextual (allowed if user is owner or org member).

- Create a stable set of permission strings (or enums) that your server can check quickly.

- Map roles to permissions in one place (config or database), not scattered across resolvers.

Where to Enforce Authorization in a GraphQL Server

You can enforce authorization in several places, and mature systems often use more than one. Common enforcement points include: schema directives (declarative), resolver wrappers/middleware (centralized), and data-source layer checks (closest to data). The key is consistency: whichever approach you choose, it must be hard to bypass. If you only check in top-level resolvers, nested resolvers might leak data. If you only check in field resolvers, a list query might still reveal existence of objects through IDs or counts.

A robust pattern is “defense in depth”: operation-level checks at the resolver entry, plus object/field checks at resolution time, plus data-source constraints (like filtering by tenant/org) so that even a missing check does not return cross-tenant data. This chapter focuses on RBAC and field-level permissions, so the examples will show resolver and directive patterns, but you should still ensure your underlying queries are tenant-safe.

Operation-Level RBAC: Guarding Queries and Mutations

Operation-level authorization is the simplest: before executing the resolver logic, verify the caller has the required permission. This is ideal for admin mutations and privileged queries. It also improves performance by failing fast before expensive downstream calls. In GraphQL, operation-level checks are typically implemented as resolver wrappers or middleware that reads context (which contains the authenticated principal and their permissions) and throws a “forbidden” error if not allowed.

Step-by-step: Implement a reusable requirePermission guard

// Pseudocode (Node/TypeScript style) - adapt to your server framework

class ForbiddenError extends Error {

constructor(message = 'Forbidden') { super(message); }

}

type Context = {

principal: { userId: string; roles: string[]; permissions: Set<string> } | null;

};

function requirePermission(permission: string) {

return (resolver: any) => async (parent: any, args: any, ctx: Context, info: any) => {

if (!ctx.principal) throw new ForbiddenError('Authentication required');

if (!ctx.principal.permissions.has(permission)) throw new ForbiddenError('Missing permission');

return resolver(parent, args, ctx, info);

};

}

// Usage: wrap a resolver

const resolvers = {

Mutation: {

deleteUser: requirePermission('user:delete')(async (_: any, { id }: any, ctx: Context) => {

// ... perform deletion

return true;

})

}

};Keep the permission mapping centralized. For example, translate roles to permissions when building the context, so resolvers only check permissions. This reduces coupling between business logic and identity representation.

Object-Level Authorization: Ownership and Tenancy Checks

RBAC alone is often insufficient because many rules are contextual: a user can read their own profile but not others; an org admin can manage users in their org but not in other orgs. These are object-level checks. In GraphQL, object-level authorization must be applied wherever objects are fetched, including list queries and nested fields. A common approach is to encode “visibility constraints” into the data access layer (for example, always filter by orgId from context), and then apply additional checks for special cases (like support staff who can access multiple orgs).

When object-level rules are not enforced at the data layer, you risk “IDOR” (insecure direct object reference): a caller guesses an ID and fetches an object they should not see. GraphQL makes this easy to exploit because IDs are often exposed widely. Even if you use opaque IDs, attackers can still obtain IDs through other queries unless you enforce object-level checks consistently.

Step-by-step: Apply object constraints in list and node fetches

- Identify entry points that fetch objects by ID (e.g.,

user(id),node(id)). - Ensure the fetch function accepts

contextand applies tenant/org constraints. - For list queries, filter by the caller’s accessible scope (org membership, project membership).

- For nested resolvers, avoid refetching without constraints; pass parent identifiers and re-check scope.

Field-Level Authorization: Read and Write Controls Per Field

Field-level authorization decides whether a caller can read or write a specific field. In GraphQL, “write” typically occurs through mutations and input types, but the effect is still field-level: can the caller set User.role? can they set User.email? can they set Organization.plan? For reads, field-level checks prevent sensitive data from being returned even when the object itself is visible.

There are two main strategies for read permissions: (1) throw an authorization error when a forbidden field is requested, or (2) return null for that field (possibly with an error entry) while allowing the rest of the response. The choice depends on your product requirements and how clients handle partial data. A common pattern is: for truly sensitive fields (secrets, tokens), deny with an error; for “optional visibility” fields (like internal notes), return null and optionally include a structured error so clients can distinguish “not set” from “not allowed.”

Implementing field checks in resolvers

// Example: field resolver with a permission check

const resolvers = {

User: {

email: async (user: any, _: any, ctx: Context) => {

if (!ctx.principal) return null; // or throw

const isSelf = ctx.principal.userId === user.id;

const canReadSensitive = ctx.principal.permissions.has('user:read:sensitive');

if (!isSelf && !canReadSensitive) return null;

return user.email;

},

lastLoginAt: async (user: any, _: any, ctx: Context) => {

if (!ctx.principal?.permissions.has('audit:read')) throw new ForbiddenError();

return user.lastLoginAt;

}

}

};This approach is explicit and easy to test, but can become repetitive. To reduce duplication, you can use higher-order functions, resolver middleware, or schema directives that wrap field resolvers automatically.

Schema Directives for Declarative Authorization

Schema directives let you annotate fields and types with authorization requirements, keeping policy close to the schema. For example, @requires(permission: "audit:read") on User.lastLoginAt. The server then enforces the directive by wrapping resolvers at schema build time. This can dramatically reduce boilerplate and makes it easier to review authorization during schema changes.

Directives work best for rules that are mostly static (role/permission based). For contextual rules (ownership, org membership), directives can still help, but you need a way to reference runtime data (parent object, arguments) and context. In practice, teams often use directives for coarse rules and keep complex checks in resolvers or policy functions.

Step-by-step: Add a @requires directive for permissions

# SDL example

directive @requires(permission: String!) on FIELD_DEFINITION

type User {

id: ID!

email: String @requires(permission: "user:read:sensitive")

lastLoginAt: DateTime @requires(permission: "audit:read")

}// Pseudocode directive implementation idea

function wrapFieldResolverWithRequires(schema: any) {

// Iterate fields; if @requires exists, wrap resolver with permission check

// The wrapper reads ctx.principal.permissions

return schema;

}Even with directives, consider exceptions like “self can read email.” You can model that as a different directive (e.g., @requiresAny(permissions: [...])) plus a separate “self” rule, or handle it in a dedicated policy function for that field.

Policy Functions: Centralize Logic Without Losing Flexibility

To avoid scattering authorization logic, create policy functions that encapsulate rules per domain. A policy function takes context, the target object, and sometimes arguments, and returns allow/deny (and optionally a reason). Resolvers call these policies, and directives can also call them. This yields a single source of truth while still supporting contextual checks.

// Pseudocode policy module

const UserPolicy = {

canReadEmail(ctx: Context, user: any) {

if (!ctx.principal) return false;

if (ctx.principal.userId === user.id) return true;

return ctx.principal.permissions.has('user:read:sensitive');

},

canUpdateRole(ctx: Context) {

return !!ctx.principal && ctx.principal.permissions.has('user:manage');

}

};Policies also improve testing: you can unit test policy functions with a matrix of roles, permissions, and object ownership without running a full GraphQL execution.

Write Authorization: Validating Inputs and Protecting Sensitive Updates

Field-level write authorization is often overlooked because GraphQL mutations feel “operation-level.” But most security issues happen when a caller can set fields they should not. For example, a mutation updateUser(input) might allow updating name and email, but must not allow setting role or mfaEnabled unless the caller has elevated permissions. You should treat each input field as a write target with its own rule.

A practical approach is to validate the input against a “write mask” derived from permissions. If the input contains forbidden fields, reject the request with a clear error. This is safer than silently ignoring fields because silent ignores can hide client bugs and make auditing harder.

Step-by-step: Enforce per-field write rules in a mutation

// Example mutation resolver enforcing write permissions

async function updateUser(_: any, { id, input }: any, ctx: Context) {

if (!ctx.principal) throw new ForbiddenError('Authentication required');

const isSelf = ctx.principal.userId === id;

// Allowed fields for self-service

const selfAllowed = new Set(['name', 'email']);

// Elevated fields

const adminAllowed = new Set(['role', 'status', 'mfaRequired']);

for (const key of Object.keys(input)) {

const allowed = (isSelf && selfAllowed.has(key)) ||

(ctx.principal.permissions.has('user:manage') && adminAllowed.has(key)) ||

(isSelf && selfAllowed.has(key));

if (!allowed) throw new ForbiddenError(`Not allowed to set field: ${key}`);

}

// Proceed with update using only validated fields

return /* updated user */;

}Also consider “derived” authorization: even if a caller can update email, you might require recent authentication, verified session, or additional checks. Keep those requirements in the policy layer so they are consistently applied.

Handling Partial Results and Errors for Forbidden Fields

GraphQL can return partial data with errors. Decide your strategy for forbidden fields and keep it consistent. If you throw an error in a field resolver, GraphQL will null that field (or bubble null up depending on non-null types) and include an error entry. This can be useful for debugging and for clients that can handle partial data. However, error messages must not leak sensitive information (for example, “user exists but you’re not allowed” can become an enumeration vector). Prefer generic messages like “Forbidden” and avoid including identifiers or internal rule details.

If you choose to return null without an error for some fields, document it for client teams and ensure the schema reflects optionality. For example, if User.email might be hidden, it should be nullable in the schema, or you must accept that authorization failures can cause null bubbling that removes larger parts of the response. Many teams intentionally keep sensitive fields nullable to avoid cascading nulls.

Performance Considerations: Avoid Per-Field Permission Lookups

Field-level authorization can become expensive if each field triggers database checks (e.g., “is caller an org admin?”) repeatedly across a list. Optimize by computing permissions and scopes once per request and storing them in context, and by batching any required membership checks. For example, if resolving Organization.members.email for many users, you do not want to query membership for each user-field pair. Instead, precompute “accessible org IDs” and “isOrgAdmin(orgId)” in a cached structure, or batch membership checks by org.

A practical pattern is to store in context: permissions (set), tenantId/orgId, and optionally a “scope object” like ctx.access = { orgIds: [...], projectIds: [...] }. Field resolvers and policies then do constant-time checks against these sets. If you must consult the database, do it once and cache the result for the request lifetime.

Auditing and Testing Authorization Rules

Authorization is easiest to break during schema evolution: new fields, new relationships, new mutations. Build a testing strategy that covers RBAC and field-level permissions as first-class behavior. Unit test policy functions with role/permission matrices. Add integration tests that execute representative GraphQL operations for different personas (anonymous, user, org admin, support, super admin) and assert both data visibility and error behavior. Also test “alternate paths” to the same data to ensure path-independent enforcement.

Step-by-step: Create an authorization test matrix

- Define personas: anonymous, basic user, org member, org admin, support, super admin.

- For each persona, list allowed operations and forbidden operations.

- For key types, list sensitive fields and expected visibility per persona.

- Write tests that query the same sensitive field through multiple query shapes (direct, nested, list).

- Include negative tests for write attempts: try setting forbidden input fields and assert rejection.

Common Pitfalls and Safer Defaults

Several mistakes recur in GraphQL authorization implementations. First, relying on client-side hiding: if it’s in the schema, it can be requested. Second, checking only at top-level resolvers and forgetting nested resolvers. Third, using role checks directly everywhere, which makes refactoring roles risky and encourages inconsistent rules. Fourth, making sensitive fields non-nullable, which can cause unexpected null bubbling and larger data loss when authorization denies a field. Fifth, returning overly specific error messages that enable resource enumeration.

Safer defaults include: deny-by-default for sensitive fields, central policy functions, permission-based checks rather than role-name checks, and consistent error messaging. When adding a new field, decide immediately: is it public, restricted, or conditionally visible? If restricted, implement the field-level rule at the same time as the field, and add tests that prove the restriction.