Why trade-offs create value (even when budgets and policies feel fixed)

In many non-sales negotiations—project scope discussions, cross-functional prioritization, vendor management, hiring packages, service-level agreements, or internal resource allocation—people assume the only lever is price or “yes/no.” Value creation through trade-offs is the practice of expanding what can be negotiated so both sides can get more of what they care about, without either side feeling they “lost.”

A trade-off is not simply giving something up. It is exchanging something you value less for something you value more, while the other side does the opposite. This works because parties rarely value every issue equally. One team might care most about speed; another cares most about predictability. One vendor might care about referenceability; you care about uptime. One stakeholder might care about headcount; you care about tooling. When you identify these differences and structure them into package deals, you can create agreements that outperform a single-issue compromise.

Package deals are bundles of multiple terms negotiated together (e.g., scope + timeline + support + reporting cadence + payment terms). They reduce the risk of “winning” one point while losing overall value, and they help you avoid piecemeal concessions that accumulate into a bad deal.

Core concepts: issues, priorities, and “currencies”

1) Issues: the negotiable dimensions

An issue is any term that can vary. In non-sales roles, issues often hide in operational details rather than in a formal contract. Examples include:

- Timeline: start date, milestones, delivery windows, freeze periods

- Scope: features, acceptance criteria, exclusions, change-control rules

- Quality: performance thresholds, testing depth, documentation level

- Risk allocation: warranties, liability caps, escalation paths

- Support: response times, on-call coverage, training, office hours

- Governance: meeting cadence, reporting format, decision rights

- Resources: named individuals vs pooled team, dedicated capacity

- Flexibility: cancellation terms, pause/resume options, swap rights

- Visibility: case study permission, internal demo, reference calls

- Payment mechanics: invoicing schedule, prepay discounts, net terms

When someone says “We can’t move on price,” they may still be able to move on payment timing, scope boundaries, or risk-sharing. Your job is to surface additional issues so you can trade across them.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

2) Priorities: what matters most (and least)

Trade-offs require knowing relative priorities. You do not need to reveal your full ranking, but you must understand it. A practical way is to label each issue for you as:

- Must-have: deal fails without it

- Important: high value, but flexible on how achieved

- Nice-to-have: low value; useful as trade currency

Do the same hypothesizing for the other side. You will rarely know their true ranking at the start, so you test assumptions through questions and by observing reactions to proposals.

3) Currencies: what you can give that costs you little

In non-sales roles, the best trade currencies are often non-monetary and low-cost to you but meaningful to them. Examples:

- Faster feedback cycles (you commit to 24-hour review turnaround)

- Reduced coordination overhead (single point of contact, fewer meetings)

- Predictable demand (longer commitment, forecast sharing)

- Visibility and credibility (reference, testimonial, internal showcase)

- Operational convenience (standardized templates, automated reporting)

- Risk reduction (clear acceptance criteria, fewer last-minute changes)

Value creation is frequently the art of finding these currencies and exchanging them for what you truly need.

From single-issue bargaining to multi-issue problem solving

Single-issue bargaining sounds like: “Can you do it for X?” or “Can you deliver by Friday?” It tends to produce either stalemate or a compromise that neither side loves. Multi-issue negotiation sounds like: “If we can be flexible on A, can you improve B and C?” This shift changes the conversation from “who wins” to “how do we design a workable exchange.”

Key principle: Never concede on one issue without linking it to another issue. Linking turns a concession into a trade. The language is simple:

- “If we do X, can you do Y?”

- “Assuming we can agree on A, what flexibility do you have on B?”

- “We can move on timeline if we can lock scope and acceptance criteria.”

Step-by-step: building value-creating trade-offs

Step 1: Expand the issue list beyond the obvious

Start by writing down the obvious issues (often price, timeline, scope). Then deliberately add operational and risk-related issues. A useful prompt is: “What would make this easier for them to deliver?” and “What would make this safer for us to accept?”

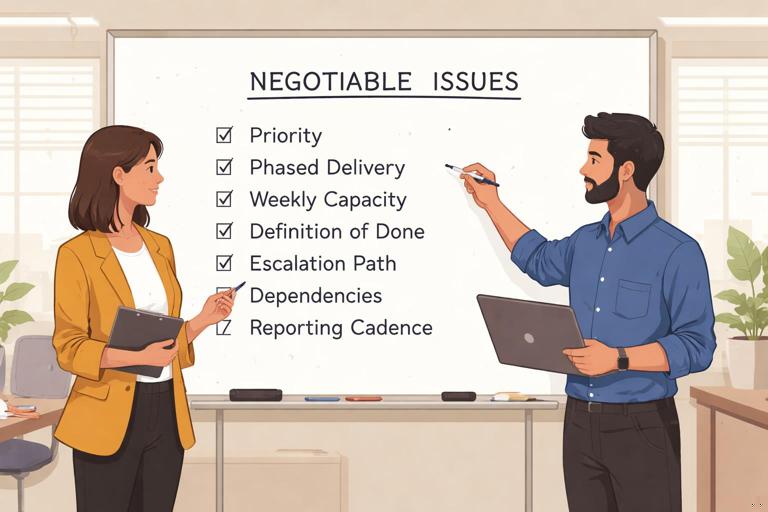

Example (internal project negotiation): You need engineering support for a compliance initiative. The obvious issue is “priority.” Expand issues to include: phased delivery, dedicated weekly capacity, definition of done, escalation path, dependency support from your team, and reporting cadence.

Step 2: Assign relative weights (simple scoring)

Use a lightweight scoring system to clarify your own preferences. For each issue, assign an importance weight from 1–5 and define what “better” means. You are not creating a perfect model; you are creating clarity.

Issue: Delivery date (Weight 5) Better = earlier, but only if quality holds

Issue: Scope (Weight 4) Better = includes audit logs + access controls

Issue: Reporting (Weight 2) Better = weekly summary email vs meeting

Issue: Payment terms (Weight 1) Better = net 45 vs net 30This helps you avoid trading away a high-weight issue for a low-weight improvement.

Step 3: Diagnose the other side’s likely priorities

Before proposing packages, gather signals. Ask questions that reveal constraints and preferences without triggering defensiveness:

- “What’s hardest about delivering this by that date?”

- “Which part of the scope drives most of the effort?”

- “If we had to simplify, what would you remove first?”

- “What does success look like for your team?”

- “What internal commitments are you managing this quarter?”

Listen for words like “risk,” “uncertainty,” “rework,” “approvals,” “capacity,” and “visibility.” These often point to trade currencies you can offer.

Step 4: Create 2–3 package options (not one)

Instead of presenting a single demand, propose multiple packages that are all acceptable to you but emphasize different priorities. This accomplishes three things: it reveals their preferences, reduces deadlock, and frames the negotiation as collaborative design.

Each package should be internally consistent: if you ask for faster delivery, you might offer reduced scope or more support from your side. If you ask for lower cost, you might offer longer commitment or fewer customizations.

Template:

- Package A (Speed): You get faster delivery; they get scope control and fewer change requests.

- Package B (Cost): You get lower cost; they get longer commitment and predictable demand.

- Package C (Risk): You get stronger guarantees; they get clearer acceptance criteria and staged sign-offs.

Step 5: Trade across issues using conditional language

When they push back on one element, avoid unlinked concessions. Use conditional trades:

- “We can accept a later date if we can add interim milestones and a weekly progress report.”

- “If we reduce the scope, can you include training and a runbook?”

- “If we commit to a 12-month term, can you improve response time and cap annual increases?”

Conditional language keeps the negotiation balanced and prevents “concession drift,” where you keep giving without receiving.

Step 6: Verify feasibility and implementation details

Value is only real if it can be delivered. Many package deals fail because operational details are vague. Convert the package into clear terms:

- Define acceptance criteria and who signs off

- Specify response times and measurement windows (e.g., “P1 within 30 minutes, 24/7”)

- Clarify what is included vs excluded

- Document change-control: how new requests are estimated and approved

- Set governance: cadence, attendees, escalation path

This step is where non-sales negotiators often add the most value: you translate “agreement” into “execution.”

Practical examples of trade-offs and package deals

Example 1: Product manager negotiating with engineering on timeline vs scope

Situation: A PM needs a feature for a partner launch. Engineering says the date is unrealistic.

Issues to negotiate: launch date, scope, quality/testing depth, partner-facing commitments, PM support (requirements clarity), and post-launch iteration plan.

Package options:

- Package A (Launch on time, reduced scope): Deliver core workflow by launch date; defer advanced settings; PM provides daily clarifications; acceptance criteria locked by end of week; post-launch sprint reserved for enhancements.

- Package B (Full scope, later launch): Deliver full settings and analytics; launch moves by 3 weeks; engineering commits to full automated tests; PM reduces stakeholder meetings to one weekly review.

- Package C (Phased launch, risk-managed): Soft launch to 10% of users on original date; full rollout 2 weeks later; engineering gets a freeze on new requirements; PM commits to partner messaging that frames phased rollout.

Why it creates value: Engineering gets reduced uncertainty and fewer late changes; PM gets a credible launch plan and avoids a binary “no.”

Example 2: HR/business partner negotiating a candidate offer package

Situation: Candidate asks for higher base salary, but comp bands are tight.

Issues to negotiate: base salary, sign-on bonus, start date, remote days, learning budget, title leveling, performance review timing, equity, and role scope.

Package options:

- Package A (Band-compliant base + sign-on): Base at top of band; one-time sign-on bonus; review at 6 months with clear criteria; start date flexible by 4 weeks.

- Package B (Equity-forward): Base slightly below top; increased equity grant; learning budget; defined project ownership in first quarter.

- Package C (Flexibility and growth): Base at band; additional remote day; conference attendance; mentorship plan; title review after successful delivery of a specified initiative.

Why it creates value: The organization stays within policy while addressing what the candidate may value (cash now, long-term upside, flexibility, growth). The candidate feels heard because the negotiation is not reduced to a single number.

Example 3: Operations lead negotiating with a vendor on service levels

Situation: Vendor won’t reduce price. You need higher reliability and faster support.

Issues to negotiate: uptime SLA, response times, escalation path, service credits, onboarding/training, reporting, contract term, payment schedule, and referenceability.

Package options:

- Package A (SLA upgrade for term): Keep price; upgrade to 99.9% uptime; P1 response within 30 minutes; you commit to a 24-month term and provide quarterly product feedback sessions.

- Package B (Support upgrade for operational ease): Keep price; add dedicated support channel and monthly health check; you standardize ticket templates and provide logs within 1 hour of incident request.

- Package C (Risk-sharing): Keep price; add service credits for missed SLA; define incident severity and measurement; you accept net-30 payment and a joint incident postmortem process.

Why it creates value: Vendor gets predictability and lower support friction; you get improved outcomes where it matters (reliability, response) without needing a price concession.

How to invent trade-offs when the other side says “nothing else is negotiable”

Sometimes you face rigid policies or a counterpart who wants to keep the negotiation narrow. Your move is to shift from “What can you change?” to “What can we design?” Use these approaches:

Ask about constraints, then trade to relieve them

If they can’t move on a term, ask what makes it hard. Constraints often reveal negotiable operational elements.

- “Is the challenge budget approval, resourcing, or risk?”

- “What would need to be true for you to be comfortable with X?”

Then offer a trade that reduces the constraint: clearer acceptance criteria, phased rollout, longer lead time, fewer stakeholders, or reduced variability.

Introduce contingent agreements (when uncertainty is the blocker)

If disagreement comes from different forecasts (e.g., workload, adoption, incident volume), propose a contingent term that adjusts based on what happens.

Examples:

- “If usage exceeds 10,000 active users, we move to tier-2 pricing; otherwise we stay at tier-1.”

- “If we miss the milestone due to our delayed feedback, we extend the date without penalty.”

- “If uptime falls below 99.5% in a month, service credits apply automatically.”

Contingent agreements turn arguments about the future into rules for handling the future.

Trade process improvements for outcome improvements

Many negotiations stall because delivery teams fear chaos: unclear requirements, constant changes, slow approvals. Offer process discipline in exchange for better outcomes.

- You provide a single decision-maker and a 48-hour approval SLA

- You agree to a change-control board and a weekly backlog freeze

- You commit to providing test data and environments by a specific date

Process trades are powerful because they often cost you little but reduce their risk significantly.

Package deal design patterns you can reuse

Pattern 1: “Speed for certainty”

You ask for faster delivery; you offer reduced uncertainty.

- You lock requirements by a date

- You limit stakeholders and feedback loops

- You accept phased delivery

Pattern 2: “Discount for commitment” (even internally)

You ask for a better rate or higher priority; you offer longer-term commitment or predictable demand.

- Multi-quarter roadmap commitment

- Reserved capacity planning

- Standardization across teams (fewer custom requests)

Pattern 3: “Quality for flexibility”

You ask for higher quality or stronger guarantees; you offer flexibility elsewhere.

- More lead time

- Off-peak maintenance windows

- Staged acceptance and clear defect definitions

Pattern 4: “Risk-sharing”

You reduce your downside while keeping the deal attractive.

- Service credits tied to measurable metrics

- Pilot period with exit option

- Joint governance and escalation

Common mistakes that destroy value (and how to avoid them)

Making unilateral concessions

If you say “Okay” repeatedly without getting anything back, you train the other side to ask for more. Replace “Okay” with a trade: “We can do that if we can also…”

Negotiating issues one at a time

Piecemeal bargaining hides the total cost. Insist on bundling: “Let’s look at timeline, scope, and support together so we can land a balanced plan.”

Offering packages where only one is acceptable to you

Counterparts can sense fake choices. Ensure each package is genuinely workable. If one is your clear favorite, make the others still viable so their selection reveals priorities rather than triggering distrust.

Vague terms that can’t be executed

“Better support” and “high priority” are not operational. Define metrics, hours, escalation steps, and responsibilities. Package deals should read like an implementation plan, not a wish list.

Mini toolkit: phrases and a simple worksheet

Phrases to propose trade-offs and packages

- “Let’s bundle a few terms so we can create options.”

- “If we’re flexible on X, what flexibility do you have on Y?”

- “Here are three packages—each works for us—tell me which is closest to what you need.”

- “What would you need from us to make that feasible?”

- “Can we make that contingent on actual volume/usage?”

One-page worksheet (copy/paste)

1) Issues (list 8–12):

-

-

2) Our priorities (Must/Important/Nice) + weight (1–5):

- Issue: Priority: Weight:

3) Hypothesis of their priorities:

- Issue: Likely priority signal:

4) Trade currencies we can offer (low cost to us):

-

-

5) Package A (emphasize speed):

- We give:

- We get:

6) Package B (emphasize cost/predictability):

- We give:

- We get:

7) Package C (emphasize risk/quality):

- We give:

- We get:

8) Implementation specifics to document:

- Acceptance criteria:

- Change control:

- Governance cadence:

- Escalation path:

- Metrics and measurement windows: