Why stakeholder mapping matters in non-sales negotiations

In non-sales roles, many negotiations are not decided at the table. They are decided before the meeting, through internal alignment: who supports the proposal, who can block it, who must implement it, and who will be blamed if it fails. Stakeholder mapping is the structured process of identifying those people (and groups), understanding what they care about, and planning how to engage them so that your negotiation has a stable internal foundation.

Internal alignment is the companion discipline: turning a collection of individual preferences into a coherent organizational position. Without alignment, you may negotiate a deal that looks good on paper but collapses during approval, procurement review, legal review, security review, or implementation. With alignment, you can negotiate faster, make credible commitments, and avoid last-minute surprises such as “Finance won’t approve,” “Security needs a different clause,” or “Operations can’t support that timeline.”

Core concepts: stakeholders, influence, and alignment

What counts as a stakeholder

A stakeholder is anyone who can affect the negotiation outcome or is affected by it. In internal negotiations, stakeholders include managers, peers, cross-functional partners, and executive sponsors. In external negotiations, stakeholders include internal approvers and implementers as well as the counterpart’s stakeholders (to the extent you can infer them).

- Decision makers: People who can approve or reject (budget owner, VP, procurement lead).

- Influencers: People whose opinion shapes the decision (architect, security lead, senior analyst, trusted advisor to the exec).

- Implementers: People who must execute the agreement (IT ops, customer support, HR operations).

- Gatekeepers: People who control access to decision makers or process steps (EA, procurement coordinator, legal intake team).

- Beneficiaries and impacted groups: People who gain value or bear costs (end users, frontline staff, regional teams).

- Risk owners: People accountable for compliance, security, safety, or reputational risk (CISO org, compliance, data protection officer).

Power vs. interest vs. impact

Stakeholder mapping works because it separates three dimensions that are often confused:

- Power: Ability to block, approve, or materially change the deal.

- Interest: Level of attention and emotional investment in the outcome.

- Impact: Degree to which the agreement changes their workload, metrics, or risk exposure.

A person can have high impact but low power (an operations team that must implement a new process but cannot approve it). Ignoring them creates implementation failure. Another can have high power but low interest (a CFO who signs off if the numbers look standard). Your engagement plan differs for each.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Internal alignment as a negotiation asset

Alignment is not just “getting buy-in.” It is creating a shared, decision-ready package: a clear recommendation, known trade-offs, pre-vetted constraints, and a plan for execution. When you are aligned internally, you can negotiate externally with confidence because you know what you can offer, what you cannot, and what will require escalation.

When to map stakeholders (and when to refresh)

Map stakeholders early enough that you can still change the plan. A practical rule: create the first map as soon as you can answer “What decision is being made?” and “By when?” Refresh the map whenever one of these changes:

- Scope expands (new regions, new data types, new teams).

- Timeline compresses (sudden executive urgency).

- Risk profile changes (security incident, regulatory update).

- Budget source changes (different cost center, new approver).

- A key person changes roles (new manager, reorg).

Step-by-step: build a stakeholder map you can use

Step 1: Define the decision and the “decision path”

Stakeholder mapping becomes vague if you map “everyone.” Start by defining the specific decision you need. Examples:

- Approve a vendor contract with a 12-month commitment.

- Approve headcount for a new analyst role.

- Agree on a cross-team SLA for incident response.

Then outline the decision path: the sequence of approvals and reviews required. Even a rough path helps you identify hidden stakeholders. For example: manager approval → finance check → procurement intake → security review → legal redlines → VP signature → implementation kickoff.

Step 2: Brainstorm stakeholders using categories

Use a checklist so you do not miss quiet blockers:

- Budget: finance partner, cost center owner, FP&A.

- Risk: security, privacy, compliance, audit.

- Process: procurement, legal, vendor management.

- Technical: architecture, IT operations, data engineering.

- Business: product owner, operations lead, customer success.

- Change management: training, internal comms, HR (if roles change).

Add external stakeholders only if they influence your internal decision (e.g., a regulator, a strategic partner, a key customer requirement).

Step 3: Score each stakeholder on power, interest, and impact

Create a simple scoring model (1–5) for each dimension. Keep it lightweight; the goal is clarity, not precision. Example fields:

- Name / role

- Power (1–5)

- Interest (1–5)

- Impact (1–5)

- Likely stance (support / neutral / oppose / unknown)

- Primary concerns (cost, risk, timeline, workload, precedent)

- What they need to say “yes” (evidence, controls, options)

- Best channel (1:1, email brief, workshop, steering meeting)

You can visualize this as a power-interest grid, but the scoring table is often more actionable because it captures “what they need.”

Step 4: Identify the “critical few” and the “silent critical”

Not all stakeholders deserve equal attention. Identify:

- Critical few: High power stakeholders who must be actively managed.

- Silent critical: High impact implementers or risk owners who may not attend decision meetings but can derail execution later.

A common failure pattern is focusing only on the critical few (executives) and ignoring the silent critical (security reviewer, operations lead). The deal gets approved and then stalls in implementation or gets reopened.

Step 5: Build an engagement plan with specific asks

For each critical stakeholder, define a concrete objective for the interaction. Avoid vague goals like “get buy-in.” Use goals like:

- Confirm acceptance criteria for security controls.

- Validate that the proposed timeline is operationally feasible.

- Secure agreement on budget split across departments.

- Pre-approve fallback options if the vendor rejects a clause.

Then choose the right format:

- 1:1 pre-wire for high power stakeholders: short, focused, with a clear ask.

- Working session for implementers: surface constraints and create ownership.

- Written brief for low-interest approvers: make it easy to approve quickly.

Step 6: Document alignment in a one-page “internal negotiation brief”

To keep alignment durable, capture it in a short artifact that can travel across meetings. A useful template includes:

- Decision needed and deadline

- Recommended option and why

- Non-negotiable requirements (e.g., compliance controls)

- Pre-approved trade-offs (what you can flex)

- Open questions and owners

- Approval list and status

This brief reduces re-litigation because it makes the current agreement visible and reduces reliance on memory.

Practical tools and templates

Tool 1: Power–Interest–Impact grid (quick segmentation)

Use a 2x2 grid for power and interest, then annotate impact as a label (H/M/L). This helps you decide how to spend time.

- High power / high interest: manage closely (frequent updates, involve in trade-offs).

- High power / low interest: keep satisfied (concise brief, highlight risk and cost controls).

- Low power / high interest: keep informed (use them as sensors for issues).

- Low power / low interest: monitor (minimal effort).

Then check: are any high-impact implementers sitting in low-power boxes? If yes, schedule a working session anyway.

Tool 2: Stakeholder interview script (10-minute version)

When you have limited time, use a consistent set of questions:

- What would make this a success for your team?

- What risks or failure modes worry you most?

- What constraints must we respect (policy, capacity, timing)?

- What evidence would you need to support approval?

- Who else should be involved before we commit?

- If we cannot get the ideal outcome, what alternative would you accept?

Capture answers in your map. Patterns across interviews often reveal the real negotiation issues (e.g., capacity constraints disguised as “policy”).

Tool 3: RACI for implementation alignment

Many negotiations fail after agreement because responsibilities are unclear. Create a RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) for the post-deal work. This is especially important when negotiating cross-team service levels or shared processes.

Work item: Vendor onboarding + access provisioning (Week 1-2) Responsible: IT Ops Accountable: IT Manager Consulted: Security, Procurement Informed: Requesting team leadUse the RACI to test feasibility: if the “Responsible” team is not in the loop, you do not have alignment.

Internal alignment patterns you can apply

Pattern: Pre-wire before the group meeting

Group meetings are for decisions, not discovery. Pre-wire means you speak with key stakeholders individually before the decision meeting to surface objections and incorporate fixes. This reduces public resistance and prevents a meeting from turning into a surprise debate.

Example: You need approval to adopt a new analytics tool. Before the steering meeting, you meet the security lead to confirm data handling requirements, then meet finance to confirm budget treatment, then meet the operations manager to confirm training capacity. In the steering meeting, you present a plan that already reflects those inputs, making approval easier.

Pattern: Separate “principle agreement” from “implementation agreement”

Sometimes stakeholders agree on the goal but disagree on the path. Split alignment into two layers:

- Principle agreement: What we are trying to achieve and why it matters.

- Implementation agreement: Who does what, by when, with what resources and controls.

This prevents a common stall: executives agree in principle, but implementers later resist because details were never negotiated internally.

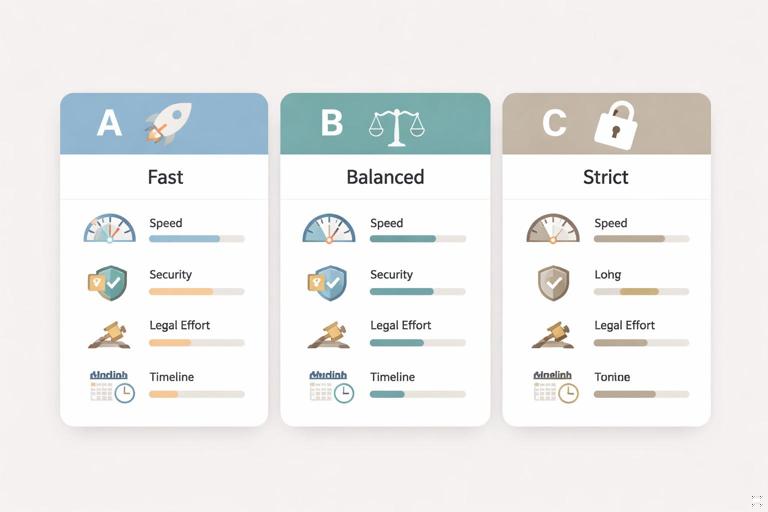

Pattern: Use “options packages” to align cross-functional teams

Cross-functional stakeholders often have incompatible preferences (e.g., security wants strict controls, product wants speed, finance wants cost certainty). Instead of arguing abstractly, present 2–3 options packages with explicit trade-offs.

Example options package for a vendor contract:

- Option A (Fast): Standard terms, minimal customization, go-live in 4 weeks, higher operational risk mitigated by monitoring.

- Option B (Balanced): Add key security addendum, go-live in 6–8 weeks, moderate legal effort.

- Option C (Strict): Full custom terms, go-live in 10–12 weeks, lowest risk but highest internal workload.

Alignment becomes a choice among packages rather than a tug-of-war over individual clauses.

Handling misalignment: common scenarios and interventions

Scenario 1: A late-stage blocker appears (“Legal says no”)

This often means legal was not engaged early enough or did not have clear context. Interventions:

- Ask legal for the specific clause(s) and the underlying risk they are managing.

- Identify whether the issue is policy-based (non-negotiable) or preference-based (negotiable).

- Bring a small working group (you + legal + business owner) to craft acceptable alternatives.

- Update the internal brief so everyone knows what changed and why.

Stakeholder mapping reduces this by identifying legal as a risk owner and scheduling an early review with a focused ask.

Scenario 2: Implementers quietly resist (“Ops can’t support this”)

Quiet resistance is common when implementers feel decisions are imposed. Interventions:

- Run an implementation feasibility check: capacity, tooling, training, on-call load.

- Offer choices: timeline extension, scope reduction, phased rollout, or temporary support.

- Make ownership explicit via RACI and confirm the accountable leader agrees.

In your stakeholder map, implementers should be tagged as high impact even if they have low formal power.

Scenario 3: Two executives disagree on direction

When power is split, alignment requires a structured escalation path.

- Clarify the decision rights: who is the final accountable executive for this domain?

- Prepare a short comparison of options with implications for each executive’s metrics.

- Propose a tie-breaker principle (e.g., customer risk, regulatory exposure, total cost).

- Pre-wire both executives separately to understand their red lines and acceptable alternatives.

Your stakeholder map should include not only the executives but also their trusted influencers (chief of staff, senior advisors) who can shape the conversation.

Example: stakeholder mapping for a cross-team SLA negotiation

Imagine you are a program manager negotiating an internal SLA between Engineering and Customer Support for incident response. The negotiation is internal, but the stakes are real: response times affect customer churn and engineering workload.

Stakeholders (sample)

- Support Director (Power 4, Interest 5, Impact 5): wants faster response and clear escalation paths.

- Engineering Manager (Power 4, Interest 4, Impact 5): wants protection from constant interruptions and realistic on-call expectations.

- SRE Lead (Power 3, Interest 4, Impact 5): cares about incident process quality and alert hygiene.

- Product VP (Power 5, Interest 3, Impact 3): cares about customer experience and roadmap impact.

- Finance Partner (Power 2, Interest 2, Impact 2): cares if new headcount or tooling is required.

- Frontline agents (Power 1, Interest 5, Impact 4): need clarity and training; can surface failure modes early.

Engagement plan (sample)

- 1:1 with Engineering Manager: agree on what qualifies as P1/P2, acceptable paging frequency, and possible mitigations (triage rotation, better runbooks).

- Working session with SRE + Support leads: draft escalation workflow and define required incident data fields.

- Brief Product VP: present 2 options packages (faster SLA requires investment; slower SLA risks churn) and ask for a decision principle.

- Pilot with frontline agents: test the workflow for one month and collect metrics.

Internal alignment artifact: a one-page SLA proposal with definitions, metrics, responsibilities, and a pilot plan. This prevents the negotiation from becoming a recurring argument every time an incident occurs.

Example: stakeholder mapping for an external vendor negotiation (internal alignment focus)

You are an HR operations lead negotiating with a benefits vendor. The external negotiation is with the vendor, but internal alignment determines what you can credibly commit to and what terms you must insist on.

Hidden stakeholders to map

- Payroll team (implementation and data integration impact)

- IT security (SSO, data encryption, access controls)

- Legal (data processing agreement, liability)

- Finance (pricing model, renewal terms)

- Employee communications (rollout messaging, training)

Alignment actions

- Run a 30-minute security intake to confirm minimum controls and documentation required from the vendor.

- Ask payroll for a feasibility estimate and blackout dates (e.g., year-end processing).

- Pre-approve a small set of contract fallbacks with legal (e.g., acceptable limitation of liability range, acceptable breach notification window).

- Confirm finance’s preferred pricing structure (per-employee vs. flat fee) and what variability is acceptable.

With this alignment, you can negotiate with the vendor without repeatedly pausing to “check internally,” which strengthens your position and reduces cycle time.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

Mistake: Mapping titles instead of real influence

Influence is not always tied to seniority. The architect who reviews integrations may have more blocking power than a director who is only loosely involved. Validate influence by asking: “Who must sign off?” and “Who can stop this in practice?”

Mistake: Treating alignment as a one-time event

Alignment decays as conditions change. Use your internal brief as a living document and schedule quick check-ins at key milestones (before sending terms, before final approval, before implementation kickoff).

Mistake: Over-involving everyone too early

Inviting too many stakeholders to early discussions can create noise and slow progress. Start with discovery in small groups, then broaden once you have options packages and clear asks. Stakeholder mapping helps you decide who needs deep involvement vs. who needs a concise update.

Mistake: Ignoring incentives and metrics

Stakeholders respond to what they are measured on. When you capture “primary concerns,” translate them into metrics: uptime, cost variance, audit findings, time-to-hire, customer churn, ticket backlog. Alignment improves when you show how the proposal protects or improves those metrics.

Checklist: internal alignment readiness before you negotiate externally

- All required approvers and reviewers identified (no unknown gatekeepers).

- Risk owners consulted and their minimum requirements documented.

- Implementers confirmed feasibility and capacity; RACI drafted.

- Options packages prepared with explicit trade-offs.

- Pre-approved fallback positions documented for predictable sticking points.

- One-page internal negotiation brief updated and shared with key stakeholders.

- Escalation path defined if stakeholders disagree late in the process.