Why preparation frameworks matter in non-sales negotiations

In non-sales roles, negotiation often happens under time pressure and with incomplete information: prioritizing work with another team, agreeing on scope with a vendor, setting timelines with a project sponsor, or resolving resource conflicts. Stress rises when you feel you might miss a hidden constraint, overcommit, or get surprised in the meeting. Preparation frameworks reduce that risk by turning “I hope this goes well” into a repeatable process that surfaces assumptions, quantifies trade-offs, and creates ready-to-use language for the conversation.

Good preparation does not mean writing a long document. It means doing the smallest amount of structured thinking that reliably prevents avoidable mistakes: agreeing to terms you cannot deliver, failing to ask for what you need, or letting the other side anchor the discussion with numbers and deadlines that become “default truth.” The goal is to walk into the negotiation with: (1) a clear picture of the decision you are trying to make, (2) a small set of options you can propose, (3) a plan for uncertainty, and (4) a way to keep the conversation calm and productive even if the other side pushes.

Framework 1: The “Decision Brief” (one page) to reduce ambiguity

A Decision Brief is a one-page preparation template that forces clarity before you negotiate. It is especially useful when you are negotiating internally (cross-functional) because ambiguity is the main risk: people leave meetings with different interpretations of what was agreed.

Step-by-step: build a Decision Brief in 15–25 minutes

- 1) Decision statement (one sentence). Write the decision you need to reach in the negotiation. Example: “Agree on the launch date and minimum scope for the Q3 release.”

- 2) Context (3–5 bullets). Only facts that matter for the decision: deadlines, dependencies, constraints, current status. Avoid storytelling.

- 3) What is negotiable vs. non-negotiable (two lists). “Negotiable” might include scope, sequencing, service levels, reporting cadence. “Non-negotiable” might include legal requirements, security controls, fixed external deadlines, or hard capacity limits.

- 4) Options you can live with (2–4 options). Each option should be a package, not a single demand. Example: Option A: “Ship core features by Aug 15, defer analytics to Sept 10.” Option B: “Ship full scope by Sept 10, add two contractors funded by marketing.”

- 5) Risks and triggers (3–6 items). Identify what could break each option and what early warning signs look like. Example: “If vendor onboarding is not complete by May 5, Aug 15 becomes unrealistic.”

- 6) Ask and give (one line each per option). For each option, write what you will ask for and what you will offer. This prevents one-sided proposals that stall.

- 7) Confirmation plan. Decide how you will confirm agreement: a recap email, updated ticket scope, revised SOW, or a shared doc with version control.

Practical example: You are an operations manager negotiating with IT for a reporting dashboard. Your Decision Brief might include: Decision statement: “Agree on dashboard delivery date and data sources.” Options: (A) “Basic dashboard in 3 weeks using existing data tables; enhancements later.” (B) “Full dashboard in 6 weeks; ops provides analyst time for data cleanup.” Risks: “Data definitions not aligned; access approvals delayed.” Confirmation plan: “Update Jira epic and send recap with acceptance criteria.”

This framework reduces stress because it replaces vague “we’ll figure it out” with concrete packages and a method to lock in shared understanding.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Framework 2: Assumption Audit to prevent surprises

Many negotiations fail not because people disagree, but because they are negotiating on different assumptions. An Assumption Audit is a quick method to list, test, and prioritize assumptions before you enter the room. It reduces the risk of being blindsided by “We can’t do that because…” halfway through the conversation.

Step-by-step: run an Assumption Audit

- 1) List assumptions in three buckets. Bucket A: “About them” (their constraints, incentives, approval process). Bucket B: “About us” (capacity, policy, budget, technical feasibility). Bucket C: “About the environment” (market timing, regulatory deadlines, vendor lead times).

- 2) Mark each assumption as High/Medium/Low impact. Impact means: if wrong, would it change your proposal or your ability to deliver?

- 3) Mark each assumption as Known/Uncertain. Be honest. If you have not verified it, it is uncertain.

- 4) Create a “must-verify” list. These are assumptions that are both high impact and uncertain. Aim for 3–7 items.

- 5) Convert must-verify items into questions. Write neutral, non-accusatory questions you can ask early. Example: “What approvals are needed on your side before we can confirm the date?”

- 6) Decide what you will do if an assumption is false. Pre-plan a pivot. Example: “If legal review takes 3 weeks, we propose a phased start with non-sensitive work first.”

Practical example: You are a finance partner negotiating with a department head about a budget reforecast. Assumptions might include: “They can freeze hiring for 60 days,” “They have discretion to reallocate travel budget,” “The CFO requires a written justification for any variance above 5%.” Your must-verify questions become: “Which cost lines do you have authority to adjust without additional approvals?” and “What documentation does your leadership need to sign off?”

This framework reduces stress because you stop relying on hope and start relying on verified constraints. It also prevents you from making commitments that later collapse due to a hidden dependency.

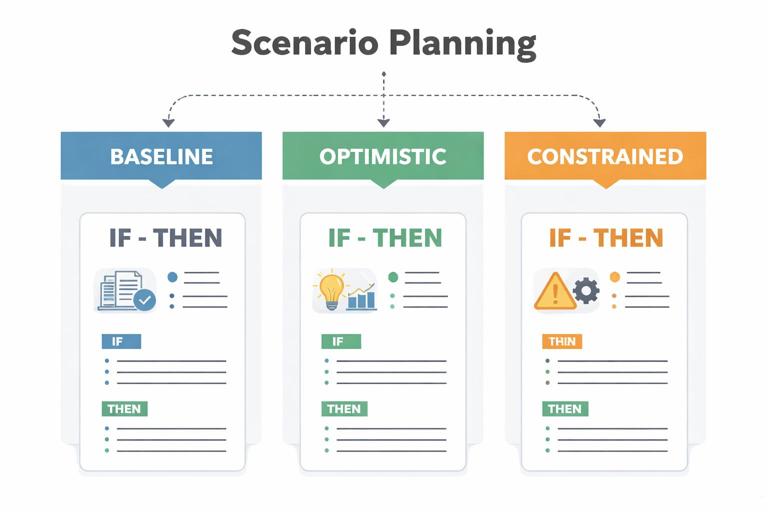

Framework 3: Scenario Planning with “If–Then” packages

Negotiations often become stressful when the other side introduces new information: a tighter deadline, a budget cut, a new compliance requirement. Scenario planning prepares you for these turns by building “If–Then” packages: conditional offers that keep you flexible without appearing indecisive.

Step-by-step: build three scenarios

- 1) Define the baseline scenario. What you expect if things go normally: typical timelines, standard resources, usual approval speed.

- 2) Define the optimistic scenario. What becomes possible if key constraints loosen (extra resources, faster approvals, fewer dependencies).

- 3) Define the constrained scenario. What you can still deliver if constraints tighten (less budget, fewer people, shorter timeline).

- 4) For each scenario, create an If–Then package. Example: “If we need the date moved up by two weeks, then we will reduce scope to X and you will provide Y.”

- 5) Prepare “decision criteria” questions. Ask what matters most so you can choose the right scenario. Example: “Is the priority hitting the date, or keeping the full feature set?”

Practical example: You are a product operations lead negotiating with customer support about a new workflow rollout. Baseline: “Roll out to 2 regions in June, 2 more in July.” Optimistic: “All regions in June if training time is doubled and a support champion is assigned per region.” Constrained: “One region in June if the knowledge base rewrite is delayed.” In the meeting, when support says, “We need all regions by end of June,” you can respond with a prepared conditional: “If end of June is fixed, then we’ll need to limit to the new ticket tags and defer the automation rules until July, and we’ll need two hours per week from your team for training.”

This framework reduces risk because you are not improvising under pressure. You are selecting from pre-built packages that protect delivery and credibility.

Framework 4: The Concession Plan (trade-offs without regret)

Stress spikes when you feel forced to give something away in the moment. A Concession Plan prevents impulsive concessions by defining what you can trade, in what order, and for what return. The key is to treat concessions as exchanges, not giveaways.

Step-by-step: create a Concession Plan

- 1) List your concession variables. Examples: timeline flexibility, scope, service levels, reporting frequency, payment terms (if relevant), meeting cadence, escalation paths, pilot vs. full rollout.

- 2) Rank them by cost to you. Cost can be time, risk, reputation, operational burden, or opportunity cost. Rank from low-cost to high-cost.

- 3) Define “currency” you want in return. Examples: faster approvals, access to data, dedicated point of contact, reduced rework, clearer acceptance criteria, resource support, executive sponsorship.

- 4) Create concession rules. Examples: “Never concede on high-cost items without getting something measurable back.” “Concede low-cost items early only if it buys goodwill or speed.”

- 5) Prepare language for trading. Write 3–5 phrases you can use calmly: “I can do X if we can agree on Y.” “If we adjust A, then we’ll need B to keep the risk manageable.”

Practical example: You are a data engineer negotiating with a marketing team requesting a custom report. Your concession variables: delivery date, number of metrics, refresh frequency, documentation level. Low-cost: documentation format. Medium: refresh frequency. High: adding new data sources. Your trade currency: a single decision-maker, stable requirements, and test cases. In the meeting, if marketing asks for daily refresh plus new sources, you can trade: “We can do daily refresh if we keep to existing sources and you provide sample outputs for validation by Friday.”

This framework reduces stress because you are not deciding what to give up while being watched. You already know your sequence and your exchange rates.

Framework 5: Risk Register for negotiations (not just projects)

A Risk Register is usually associated with project management, but it is equally useful for negotiation preparation. It helps you identify what could go wrong in the agreement itself: unclear responsibilities, unmeasurable deliverables, dependency risks, or enforcement issues. The goal is to prevent “agreement now, pain later.”

Step-by-step: build a lightweight negotiation risk register

- 1) Identify 8–12 risks. Think in categories: scope ambiguity, timeline slippage, quality disputes, handoff failures, approval delays, compliance/security, resource availability, communication breakdowns.

- 2) Rate likelihood and impact (High/Medium/Low). Keep it simple; you are prioritizing attention, not doing a statistical model.

- 3) Define mitigations as negotiation clauses or process steps. Example: “Scope ambiguity” mitigation: written acceptance criteria and a change-control process. “Approval delays” mitigation: named approver and response time expectation.

- 4) Assign an owner for each mitigation. Some mitigations are yours; others must be owned by the other side.

- 5) Turn top risks into agenda items. If it is high impact, it deserves explicit discussion, not a footnote.

Practical example: You are negotiating with an external training vendor. Risks: “Trainer substitution,” “Content not aligned to internal policy,” “Scheduling conflicts,” “Data privacy if recordings are stored externally.” Mitigations: “Named trainer in contract with substitution approval,” “Content review checkpoint,” “Cancellation/reschedule terms,” “No external storage of recordings; internal repository only.”

This framework reduces risk because it forces you to negotiate the operational details that determine whether the agreement will actually work.

Framework 6: Agenda Engineering to control pace and reduce tension

Many negotiations become stressful because the meeting structure is poor: people jump to numbers too early, sensitive topics appear at the end, or decisions are attempted without shared definitions. Agenda Engineering is the practice of designing the conversation flow so that agreement becomes easier and conflict becomes less personal.

Step-by-step: engineer a negotiation agenda

- 1) Start with shared facts and definitions. Example: define what “done” means, what the timeline labels refer to, what data source is authoritative.

- 2) Put decision criteria before options. Ask what matters most (speed, quality, cost, risk). This reduces positional arguing later.

- 3) Sequence from easy alignment to harder trade-offs. Begin with areas of agreement to build momentum, then address the biggest trade-offs.

- 4) Timebox contentious items. Example: “Let’s spend 10 minutes on timeline constraints, then 10 minutes on scope options.” Timeboxing reduces spirals.

- 5) Reserve time for recap and next steps. A negotiation without a recap is a risk event. Plan 5 minutes for “What we agreed, what remains open, who does what by when.”

Practical example agenda:

1) Confirm objective of the meeting (2 min) 2) Align on constraints and definitions (8 min) 3) Agree on decision criteria (5 min) 4) Review 2–3 option packages (15 min) 5) Confirm risks, owners, and checkpoints (8 min) 6) Recap agreements and document next steps (5 min)This framework reduces stress because it gives you a “railway track” for the conversation. When emotions rise, you can return to the structure: “Before we decide, can we confirm the criteria we’re using?”

Framework 7: Scripted language blocks for calm, professional delivery

Even with solid analysis, stress can spike when you need to say something difficult: pushing back, asking for more time, or refusing an unreasonable request. Scripted language blocks are short, reusable phrases you prepare in advance. They reduce cognitive load and help you stay respectful and firm.

Step-by-step: prepare your language blocks

- 1) Identify your high-stress moments. Examples: being asked for an immediate commitment, being blamed for delays, being pressured to accept scope creep.

- 2) Write 2–3 sentences for each moment. Keep them neutral and specific.

- 3) Include a redirect to options. The goal is not to argue; it is to move back to trade-offs and decisions.

Useful language blocks (examples):

- To slow down a forced decision: “I want to give you a reliable answer. I can confirm by tomorrow at 3 p.m. after I verify the dependency with the team.”

- To respond to an aggressive anchor: “I hear the target. To see if it’s feasible, can we walk through the constraints and what would need to change to hit it?”

- To handle scope creep: “We can add that, but it changes the effort. Which of these should we trade off: timeline, another feature, or additional resourcing?”

- To request reciprocity: “If we’re going to commit to that date, we’ll need a single point of approval and a 48-hour turnaround on feedback.”

- To protect quality: “I’m not comfortable committing to that without a definition of acceptance. Let’s write the criteria so we both know what success looks like.”

This framework reduces stress because it prevents emotional improvisation. You are less likely to sound defensive or vague, and more likely to sound measured and collaborative.

Framework 8: The “Pre-Mortem” to uncover hidden failure modes

A pre-mortem is a structured exercise where you assume the negotiation outcome failed and then work backward to identify why. It is especially helpful when the negotiation involves ongoing collaboration, because many failures come from implementation issues rather than the initial agreement.

Step-by-step: run a 10-minute pre-mortem

- 1) Imagine it is 60 days after the agreement and it is considered a failure. Write that sentence at the top: “This agreement failed because…”

- 2) List 10 reasons quickly. Speed matters; you want candid possibilities, not polished answers.

- 3) Cluster reasons into themes. Common themes: unclear ownership, unrealistic timeline, missing approvals, poor communication cadence, misaligned definitions, lack of enforcement.

- 4) Convert top themes into negotiation checkpoints. Example: “Unclear ownership” becomes a RACI-like responsibility list for the deliverables. “Missing approvals” becomes a named approver and timeline.

- 5) Decide what you will explicitly say in the negotiation. Example: “To avoid rework, can we agree that feedback will be consolidated by one person?”

Practical example: You are negotiating a shared-service arrangement with another department. Pre-mortem reasons might include: “Requests came in without required info,” “Priorities changed weekly,” “No one owned escalations,” “Service levels were assumed, not written.” You then negotiate mitigations: intake form requirements, weekly prioritization meeting, escalation path, and measurable service levels.

This framework reduces risk because it makes you address the “how it will work” details before they become conflict later.

How to combine frameworks into a repeatable preparation routine

Frameworks are most effective when combined into a short routine you can execute consistently. A practical approach is to choose a “core set” for most negotiations and add others when complexity increases.

Routine A (30–45 minutes): for common internal negotiations

- Decision Brief (10–15 min)

- Assumption Audit (10 min)

- Concession Plan (10 min)

- Agenda Engineering (5–10 min)

Routine B (60–90 minutes): for high-risk or cross-company negotiations

- Decision Brief (15–20 min)

- Scenario Planning (15 min)

- Risk Register (15–20 min)

- Pre-Mortem (10 min)

- Scripted language blocks (5–10 min)

Practical tip: Store these templates as reusable documents. The stress reduction comes from not having to invent a process each time. Over time, you will notice that your negotiations become shorter and cleaner because you surface the real issues early and propose workable packages instead of debating vague preferences.