Why “secure cluster usage” is different from “secure apps”

In a shared Kubernetes cluster, most security incidents come from misuse of cluster capabilities rather than a single vulnerable container image. Developers and automation systems interact with the Kubernetes API, create resources, and connect services over the network. “Secure cluster usage” focuses on controlling who can do what (authorization), where they can do it (tenancy boundaries), and which workloads may talk to each other (network segmentation). In Kubernetes, these map cleanly to RBAC, namespaces, and NetworkPolicies.

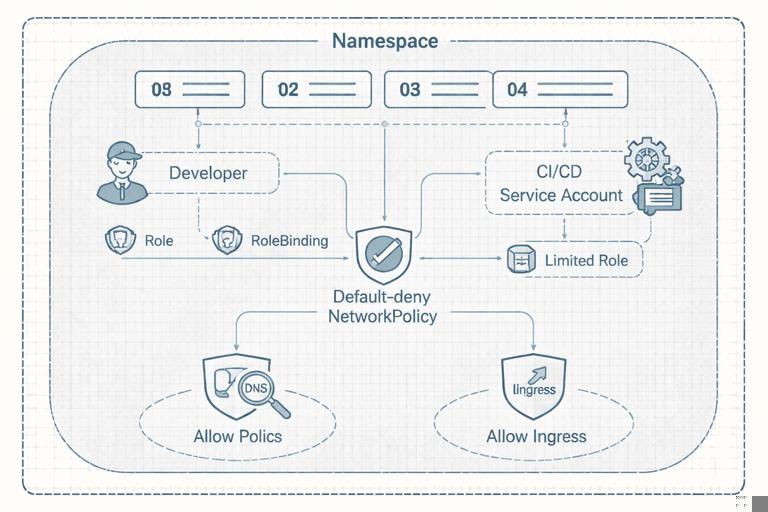

These controls are most effective when you treat them as a coherent model: namespaces provide the scope, RBAC grants permissions within that scope, and NetworkPolicies enforce least-privilege connectivity between pods. If you implement only one of them, you often end up with a “soft boundary” that can be bypassed (for example, a namespace boundary without RBAC still allows broad access if credentials are over-privileged; RBAC without NetworkPolicies still allows lateral movement over the network).

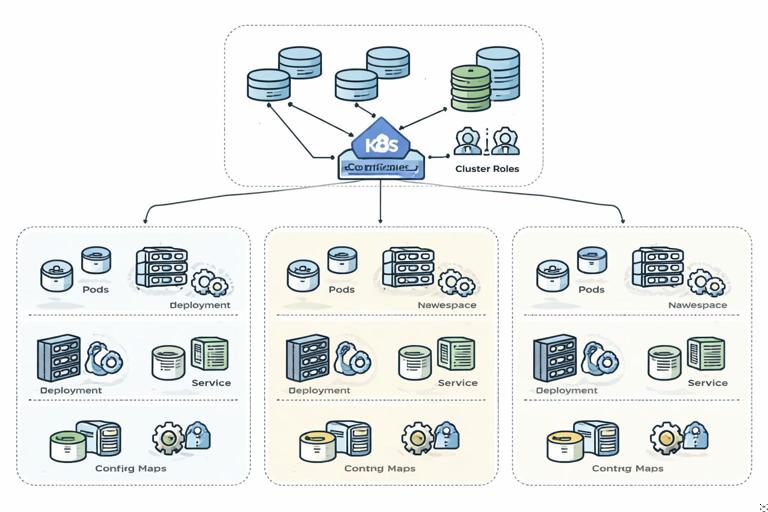

Namespaces as tenancy and blast-radius boundaries

A namespace is a logical partition of the Kubernetes API. Many resource types are namespaced (Pods, Deployments, Services, ConfigMaps), while some are cluster-scoped (Nodes, PersistentVolumes, ClusterRoles). Namespaces are not a security boundary by themselves, but they are the primary unit for organizing teams, environments, and applications, and they are the scope in which most RBAC and NetworkPolicies are applied.

Practical namespace layout patterns

- Team namespaces:

team-a,team-b. Good for platform teams running a shared cluster with multiple product teams. - App namespaces:

payments,catalog. Useful when each app has multiple components and you want app-level isolation. - Hybrid:

team-a-paymentsto avoid naming collisions and clarify ownership.

Pick a pattern that makes ownership obvious and makes it easy to apply consistent policy. Avoid putting unrelated workloads into default. Treat kube-system as off-limits for application workloads.

Create a namespace with labels for policy selection

Labels on namespaces are useful because NetworkPolicies can select pods by labels, and many policy engines (and admission controls) can target namespaces by label.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

kubectl create namespace team-akubectl label namespace team-a owner=team-a purpose=appsFrom here on, you can write policies that apply to “all namespaces with purpose=apps” (via external policy tooling) or use the namespace labels for organizational clarity and auditing.

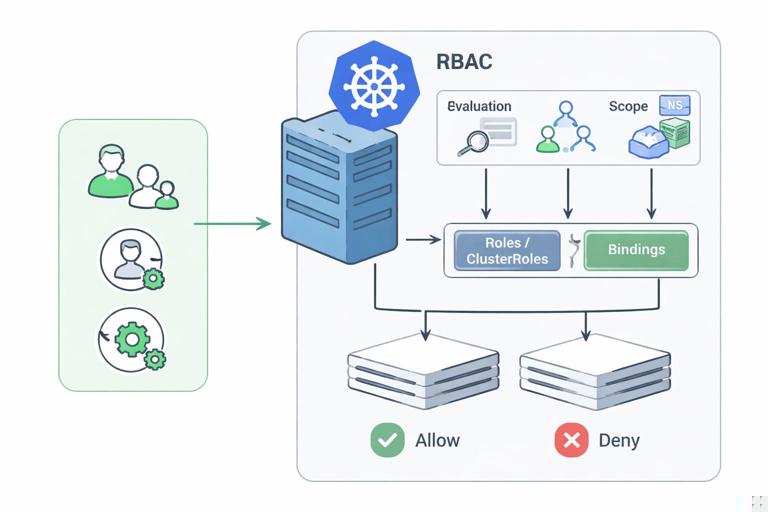

RBAC: controlling access to the Kubernetes API

RBAC (Role-Based Access Control) is Kubernetes’ built-in authorization system. It answers: “Is this authenticated identity allowed to perform this verb on this resource in this scope?” RBAC does not authenticate users by itself; it relies on authentication (certs, OIDC, service account tokens) and then authorizes requests.

Core RBAC objects and how they fit together

- Role: namespaced set of permissions (rules) for namespaced resources.

- ClusterRole: cluster-wide set of permissions; can grant access to cluster-scoped resources and can also be used within a namespace.

- RoleBinding: binds a Role or ClusterRole to a subject (user, group, or service account) within a namespace.

- ClusterRoleBinding: binds a ClusterRole to subjects cluster-wide.

Most developer access should be granted with Role + RoleBinding in a namespace. Use ClusterRoleBinding sparingly because it expands blast radius.

RBAC rules: verbs, resources, and API groups

An RBAC rule is a combination of:

- apiGroups: e.g.,

""(core),apps,batch,networking.k8s.io - resources: e.g.,

pods,deployments,services - verbs: e.g.,

get,list,watch,create,update,patch,delete

Least privilege means granting only the verbs and resources needed for the job. A common anti-pattern is giving developers "*" verbs on "*" resources in a namespace “to unblock them.” That usually becomes permanent and makes incident response harder.

Step-by-step: create a developer role scoped to a namespace

This example grants a developer the ability to view and manage typical application resources in team-a, while avoiding sensitive permissions like reading Secrets or modifying RBAC.

1) Create a Role

cat <<'YAML' > team-a-developer-role.yaml

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

name: developer

namespace: team-a

rules:

- apiGroups: ["", "apps", "batch"]

resources: ["pods", "pods/log", "services", "endpoints", "configmaps", "deployments", "replicasets", "statefulsets", "jobs", "cronjobs"]

verbs: ["get", "list", "watch", "create", "update", "patch", "delete"]

- apiGroups: ["networking.k8s.io"]

resources: ["networkpolicies"]

verbs: ["get", "list", "watch"]

YAML

kubectl apply -f team-a-developer-role.yamlNotes:

pods/logis a subresource; include it if developers need logs.- We intentionally did not include

secrets. If developers need to reference secrets, they usually don’t need permission to read them. - We allowed read-only access to NetworkPolicies so developers can understand connectivity constraints without changing them.

2) Bind the Role to a subject

In real clusters, human identities typically come from an identity provider (OIDC) and appear as users/groups. The following example binds to a group name (your cluster’s group claim mapping may differ).

cat <<'YAML' > team-a-developer-binding.yaml

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: RoleBinding

metadata:

name: developer-binding

namespace: team-a

subjects:

- kind: Group

name: team-a-developers

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

roleRef:

kind: Role

name: developer

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

YAML

kubectl apply -f team-a-developer-binding.yaml3) Verify permissions with kubectl auth can-i

Use kubectl auth can-i to test what an identity can do. If you can impersonate a user/group (cluster-admin required), you can validate the intended access.

kubectl auth can-i create deployments -n team-a --as=some.user@example.comkubectl auth can-i get secrets -n team-a --as=some.user@example.comMake permission tests part of your change review: every RBAC change should come with “can-i” examples that prove the minimal set works.

Service accounts for in-cluster automation (and how to avoid over-privilege)

Workloads running in the cluster authenticate to the API using service accounts. A common security failure is binding a powerful ClusterRole to a service account “just to make it work.” That turns a single compromised pod into a cluster-wide compromise.

Step-by-step: grant a CI job limited deploy permissions

Imagine a CI runner in team-a needs to update Deployments and read Pods for rollout status, but should not touch RBAC, Secrets, or other namespaces.

1) Create a service account

kubectl -n team-a create serviceaccount ci-deployer2) Create a Role with only required permissions

cat <<'YAML' > team-a-ci-role.yaml

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

name: ci-deployer

namespace: team-a

rules:

- apiGroups: ["apps"]

resources: ["deployments", "replicasets"]

verbs: ["get", "list", "watch", "patch", "update"]

- apiGroups: [""]

resources: ["pods", "pods/log", "events"]

verbs: ["get", "list", "watch"]

YAML

kubectl apply -f team-a-ci-role.yaml3) Bind the Role to the service account

cat <<'YAML' > team-a-ci-binding.yaml

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: RoleBinding

metadata:

name: ci-deployer-binding

namespace: team-a

subjects:

- kind: ServiceAccount

name: ci-deployer

namespace: team-a

roleRef:

kind: Role

name: ci-deployer

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

YAML

kubectl apply -f team-a-ci-binding.yamlOperational tip: if your CI runs outside the cluster, prefer short-lived credentials via your identity provider rather than exporting long-lived service account tokens. If you must use a service account token, scope it tightly and rotate it.

Common RBAC pitfalls and safer alternatives

Granting “edit” or “admin” cluster-wide

Kubernetes ships with default ClusterRoles like view, edit, and admin. Binding these cluster-wide is convenient but risky. Prefer binding them with a RoleBinding in a namespace if you use them at all.

# Safer: bind the built-in ClusterRole 'edit' only within a namespace

kubectl create rolebinding team-a-edit \

--clusterrole=edit \

--group=team-a-developers \

-n team-aAllowing access to Secrets unintentionally

Reading Secrets is effectively equivalent to reading production credentials. Many teams allow it for debugging, then forget to remove it. Instead, use application-level debugging that doesn’t require secret exfiltration, and restrict secret read access to a small set of break-glass operators.

Forgetting subresources

Developers may need pods/log or deployments/scale. If you grant broad permissions to “fix it quickly,” you lose least privilege. Add the specific subresources instead.

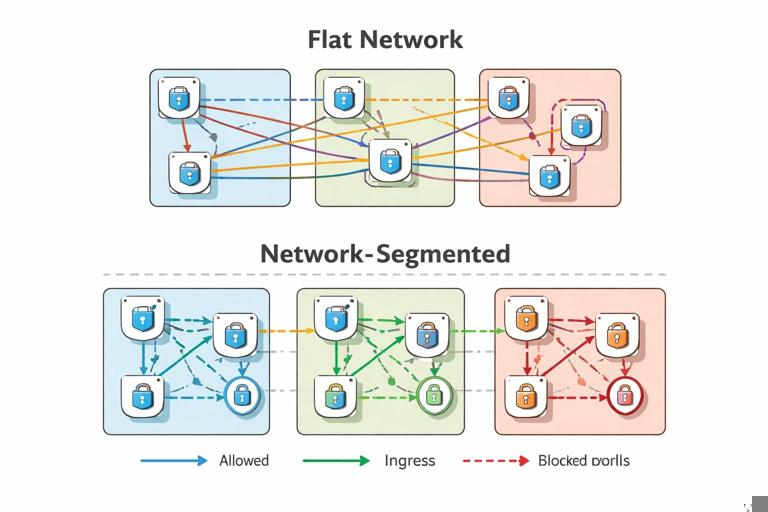

NetworkPolicies: enforcing least-privilege pod-to-pod connectivity

By default, Kubernetes networking is typically “flat”: any pod can talk to any other pod in the cluster (subject to Service exposure). NetworkPolicies let you restrict traffic at the pod level for ingress and egress. They are enforced by the cluster’s CNI plugin; if your CNI doesn’t implement NetworkPolicy, the resources will exist but won’t do anything.

How NetworkPolicies work

- Policies select target pods using

podSelector(and optionallynamespaceSelector). - Once a pod is selected by any policy for a given direction (Ingress/Egress), that direction becomes default deny for that pod, except what is explicitly allowed.

- Rules can allow traffic based on pod labels, namespace labels, and ports/protocols.

NetworkPolicies are most effective when you start with a clear labeling strategy (for example, label pods by app and component, and label namespaces by owner or purpose).

Step-by-step: implement default-deny and then open required paths

A practical approach is: (1) apply default-deny in a namespace, (2) add explicit allow rules for DNS, ingress from gateways, and app-to-app calls.

1) Default deny all ingress and egress in a namespace

cat <<'YAML' > team-a-default-deny.yaml

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: default-deny-all

namespace: team-a

spec:

podSelector: {}

policyTypes:

- Ingress

- Egress

YAML

kubectl apply -f team-a-default-deny.yamlThis selects all pods in team-a. After applying it, pods will not be able to receive or initiate connections unless you add allow policies. Apply this during a planned change window and be ready to add the necessary exceptions.

2) Allow DNS egress to kube-dns/CoreDNS

Most apps need DNS. CoreDNS typically runs in kube-system with labels like k8s-app=kube-dns (varies by distribution). This policy allows UDP/TCP 53 egress to DNS pods.

cat <<'YAML' > team-a-allow-dns.yaml

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: allow-dns-egress

namespace: team-a

spec:

podSelector: {}

policyTypes:

- Egress

egress:

- to:

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

kubernetes.io/metadata.name: kube-system

podSelector:

matchLabels:

k8s-app: kube-dns

ports:

- protocol: UDP

port: 53

- protocol: TCP

port: 53

YAML

kubectl apply -f team-a-allow-dns.yamlIf your cluster doesn’t label namespaces with kubernetes.io/metadata.name, use whatever label is present, or select the namespace by adding your own label to kube-system (if your platform allows it).

3) Allow ingress to a web app from an ingress controller namespace

Assume your web pods are labeled app=storefront and listen on port 8080. Your ingress controller runs in ingress-nginx namespace labeled purpose=ingress (label it if needed). Allow only ingress traffic from that namespace to the web pods.

cat <<'YAML' > storefront-allow-from-ingress.yaml

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: storefront-allow-from-ingress

namespace: team-a

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: storefront

policyTypes:

- Ingress

ingress:

- from:

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

purpose: ingress

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 8080

YAML

kubectl apply -f storefront-allow-from-ingress.yamlThis prevents other namespaces from directly calling the storefront pods, reducing lateral movement opportunities.

4) Allow app-to-database traffic within the namespace

Assume app=storefront needs to talk to app=postgres on 5432. You can allow egress from storefront to postgres and ingress to postgres from storefront. Many teams implement only the database ingress rule (since the client egress is already restricted by default deny).

cat <<'YAML' > postgres-allow-from-storefront.yaml

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: postgres-allow-from-storefront

namespace: team-a

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: postgres

policyTypes:

- Ingress

ingress:

- from:

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: storefront

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 5432

YAML

kubectl apply -f postgres-allow-from-storefront.yamlIf you also want to restrict storefront egress to only postgres (and DNS), add an egress policy selecting storefront pods and allowing only those destinations.

Designing labels to make policies maintainable

NetworkPolicies and RBAC both benefit from consistent labeling and naming. For NetworkPolicies, labels are the “API” you use to express intent. Avoid selecting by highly dynamic labels (like pod-template-hash). Prefer stable labels such as:

app: the application namecomponent:api,worker,dbtier:frontend,backend,dataowner: team ownership (often on namespace)

When you add a new component, you should be able to answer: “Which labels will it have, and which existing policies will select it?” If the answer is unclear, policy drift is likely.

Putting it together: a secure-by-default namespace blueprint

A repeatable pattern for each application/team namespace is:

- Create namespace with ownership labels.

- Bind developer group to a least-privilege Role (or bind built-in

view/editwithin the namespace only). - Create service accounts for automation with narrowly scoped Roles.

- Apply default-deny NetworkPolicy (Ingress + Egress).

- Add allow policies for DNS, ingress from gateways, and explicit service-to-service calls.

This blueprint can be templated and applied consistently across namespaces. The key is that the defaults should be restrictive, and exceptions should be explicit and reviewable.

Troubleshooting and validation techniques

Validate RBAC failures

When an action fails, Kubernetes returns “forbidden” errors that include the resource and verb. Use these to adjust Roles precisely rather than broadening permissions.

# Example: check what your current identity can do

kubectl auth can-i list pods -n team-a

kubectl auth can-i patch deployments -n team-aFor service accounts, you can impersonate them to test permissions (requires sufficient privileges):

kubectl auth can-i update deployments -n team-a \

--as=system:serviceaccount:team-a:ci-deployerValidate NetworkPolicy behavior

NetworkPolicy issues often look like timeouts. A systematic approach:

- Confirm your CNI enforces NetworkPolicies.

- List policies in the namespace and check which pods they select.

- Test connectivity from a pod with a known toolset (curl/nc) and compare expected vs actual.

kubectl get networkpolicy -n team-akubectl describe networkpolicy default-deny-all -n team-aIf DNS breaks, you’ll see failures resolving service names. That’s usually a missing DNS egress policy or incorrect selectors for CoreDNS.

Operational guardrails: limiting who can change the guardrails

RBAC and NetworkPolicies are only effective if they can’t be casually modified by the same actors they constrain. A common model is:

- Developers: manage workloads (Deployments, Services), view logs/events, but cannot modify RBAC or baseline NetworkPolicies.

- Platform/SRE: manage namespace-level guardrails (RBAC templates, default-deny policies, ingress allowances).

- Security: audits permissions and reviews exceptions; may own cluster-wide policies.

In RBAC terms, this means developers should not have permissions on roles, rolebindings, clusterroles, clusterrolebindings, and often not on networkpolicies either. If developers need to request connectivity changes, treat it like an interface: they propose label-based intents (source, destination, port), and a privileged role applies the policy change after review.