What “schema-first” means in GraphQL API design

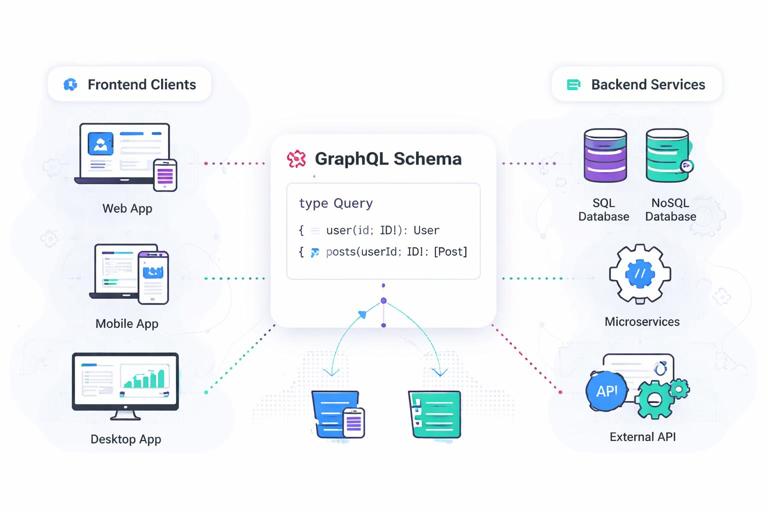

Schema-first API design treats the GraphQL schema as the primary contract that drives implementation. Instead of starting from database tables, ORM models, or REST endpoints, you start by describing the domain in GraphQL types, fields, and operations. This contract becomes the shared reference for backend and frontend teams: clients can plan queries against the schema, and server developers implement resolvers to satisfy the contract.

In practice, schema-first means you iterate on the schema in small, reviewable changes, validate it with tooling, and only then implement or adjust resolvers and data sources. The schema is not a byproduct of code; it is the design artifact that captures naming, relationships, nullability, pagination, and error semantics. When done well, schema-first enables flexible backends because you can evolve underlying services and storage without forcing clients to change, as long as the schema contract remains stable.

Design goals: flexibility, stability, and evolvability

Before writing types, define what “flexible backend” means for your product. Typically it includes: the ability to add new fields without breaking existing clients, the ability to compose data from multiple sources, and the ability to change internal implementations while keeping the external contract stable. Schema-first supports these goals by making compatibility rules explicit through field-level changes and by encouraging additive evolution.

Stability comes from careful use of nullability and from avoiding “leaky abstractions” that expose internal storage details. Evolvability comes from designing types around business concepts rather than around tables, and from planning for versionless evolution: add fields, deprecate old ones, and keep old behavior working until clients migrate.

Step-by-step workflow: from domain language to a first schema draft

Step 1: Capture domain nouns and verbs

Start by listing domain nouns (entities) and verbs (actions). Nouns often become object types; verbs often become queries or mutations. For example, in a commerce domain: nouns might be Product, Cart, Order, Customer; verbs might be addToCart, placeOrder, cancelOrder, searchProducts.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Keep the list business-oriented. Avoid naming types after microservices (e.g., InventoryServiceProduct) or database concepts (e.g., ProductRow). The schema should read like a domain model that clients can understand.

Step 2: Define object types with stable identifiers

For each noun, define an object type and decide how it is identified. Stable IDs are critical for caching, refetching, and linking between types. Prefer opaque IDs (strings) that do not encode internal meaning. If you plan to support global object identification, standardize on an ID! field named id.

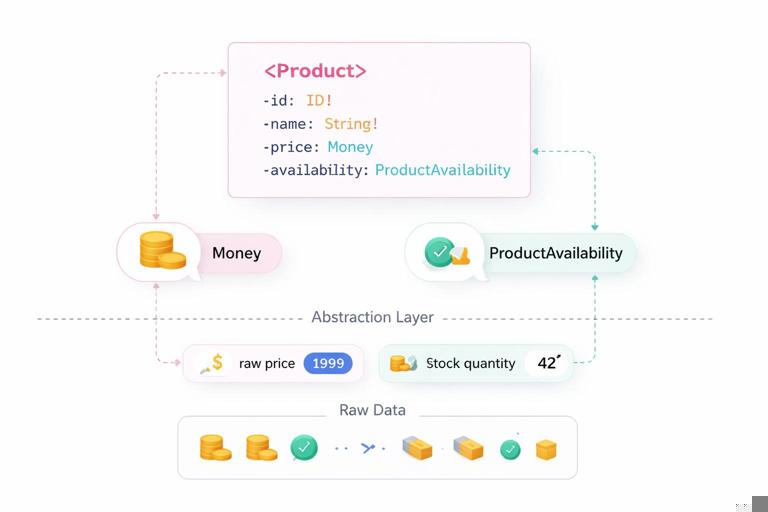

type Product { id: ID! sku: String! name: String! description: String price: Money! availability: ProductAvailability!}Notice the use of a domain-specific Money type and an availability field rather than exposing raw inventory counts unless clients truly need them. This is an example of designing for flexibility: you can change how availability is computed without changing the schema.

Step 3: Model relationships explicitly and choose list semantics

Relationships are where schemas can become either expressive or fragile. Decide whether a relationship is one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-many, and represent it with fields that return either an object or a list/connection. For lists, decide whether you need pagination now or soon. If the list could grow, design it as a connection from the start to avoid later breaking changes.

type Product { id: ID! name: String! categories: [Category!]! reviews(first: Int = 10, after: String): ReviewConnection!}Here, categories is a bounded list (often small), while reviews is potentially large and uses a connection. Schema-first design encourages you to make this decision intentionally rather than letting implementation details decide.

Step 4: Define queries around use cases, not tables

Queries should map to client use cases: fetching a product by ID, searching products, viewing the current cart, or listing orders for the current user. Avoid exposing “list all X” without filters if it is not a real use case, because it can become a performance and security liability.

type Query { product(id: ID!): Product products(search: String, categoryId: ID, first: Int = 20, after: String): ProductConnection! me: Customer cart: Cart}Note the nullability: product returns Product (nullable) to represent “not found” without forcing an error. products returns a non-null connection, even if it contains zero items, which simplifies client code and communicates that the field itself is reliably available.

Step 5: Define mutations with clear inputs and payloads

Mutations should be designed for clarity and forward compatibility. A common schema-first pattern is to use a single input object and a payload object. This allows you to add new input fields later without changing the mutation signature, and to return structured results that can grow over time.

type Mutation { addToCart(input: AddToCartInput!): AddToCartPayload!}input AddToCartInput { productId: ID! quantity: Int!}type AddToCartPayload { cart: Cart! userErrors: [UserError!]!}type UserError { code: String! message: String! field: [String!]}This pattern also separates business-level validation errors (userErrors) from transport-level GraphQL errors. Clients can handle expected failures without relying on parsing error strings.

Nullability as a design tool (and a compatibility constraint)

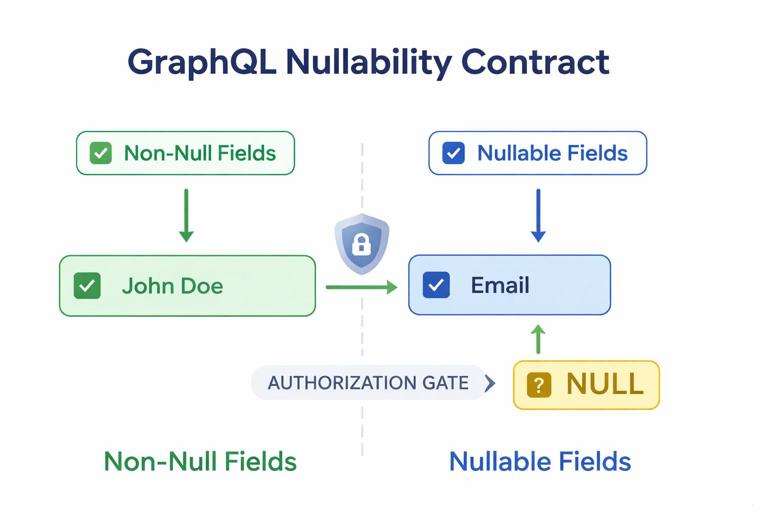

In schema-first design, nullability is not an afterthought; it is part of the contract. A non-null field (String!) promises clients that if the parent object exists, the field will be present. Changing a field from nullable to non-null is a breaking change for clients that were prepared for nulls. Changing from non-null to nullable is usually safe but can hide bugs and reduce guarantees.

Use non-null for fields that are truly guaranteed by your domain rules, such as stable IDs and required names. Use nullable for fields that may legitimately be absent, such as optional descriptions, or fields that depend on permissions (for example, email might be nullable if the viewer is not allowed to see it). If a field can be absent due to authorization, consider whether returning null is the right contract or whether the field should be moved behind a dedicated type or query that implies permission.

Designing custom scalars and value objects for clarity

Schema-first design benefits from value objects that encode meaning: Money, DateTime, URL, Locale, PhoneNumber. These improve readability and reduce ambiguity compared to plain strings. They also allow validation and consistent formatting at the schema boundary.

scalar DateTimescalar URLtype Money { amount: Decimal! currency: String!}scalar DecimalEven if your implementation uses integers for cents, the schema can present a stable, expressive representation. This decouples clients from storage and lets you evolve internal representations without changing the API contract.

Enums, unions, and interfaces: choosing the right abstraction

Enums are useful for bounded sets that change rarely, such as order status. However, adding enum values can still break some clients if they assume exhaustive handling. When you introduce enums, document that clients should handle unknown values gracefully, and consider whether a string field is safer for rapidly evolving categories.

enum OrderStatus { PENDING PAID FULFILLED CANCELED}Interfaces and unions help model polymorphism. Use an interface when multiple types share fields and clients benefit from querying those shared fields. Use a union when types are related conceptually but do not share a stable common shape.

interface Node { id: ID!}type Product implements Node { id: ID! name: String!}type Category implements Node { id: ID! title: String!}union SearchResult = Product | Categorytype Query { search(q: String!, first: Int = 10): [SearchResult!]!}This design supports flexible backends: you can add new types to SearchResult later, but remember that adding a union member can require clients to update their fragment handling. If you expect frequent expansion, consider returning a connection with a discriminated object that includes a __typename-like field usage pattern and ensure clients handle unknown types.

Pagination and filtering as first-class schema concerns

Schema-first design encourages you to standardize pagination and filtering patterns early. Inconsistent pagination across fields makes client development harder and increases server complexity. Choose a consistent approach for large lists and apply it everywhere it matters.

A connection-based design typically includes edges, node, and pageInfo. Filtering and sorting should be expressed through input objects so you can add new filters later without breaking signatures.

type ProductConnection { edges: [ProductEdge!]! pageInfo: PageInfo!}type ProductEdge { cursor: String! node: Product!}type PageInfo { hasNextPage: Boolean! endCursor: String}input ProductFilter { categoryId: ID minPrice: MoneyInput maxPrice: MoneyInput inStock: Boolean}input MoneyInput { amount: Decimal! currency: String!}enum ProductSort { RELEVANCE PRICE_ASC PRICE_DESC}type Query { products(filter: ProductFilter, sort: ProductSort = RELEVANCE, first: Int = 20, after: String): ProductConnection!}This schema is flexible because you can add new filter fields (e.g., brandId) and new sort options without changing the query name or argument structure. It is also easier to validate and document.

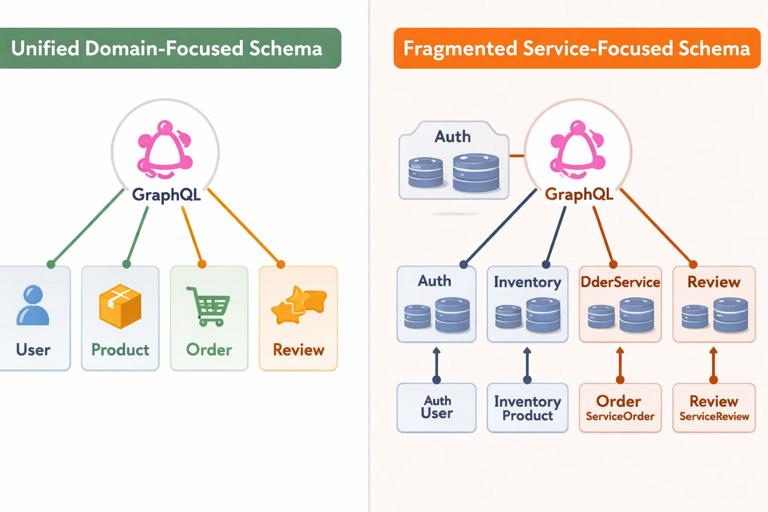

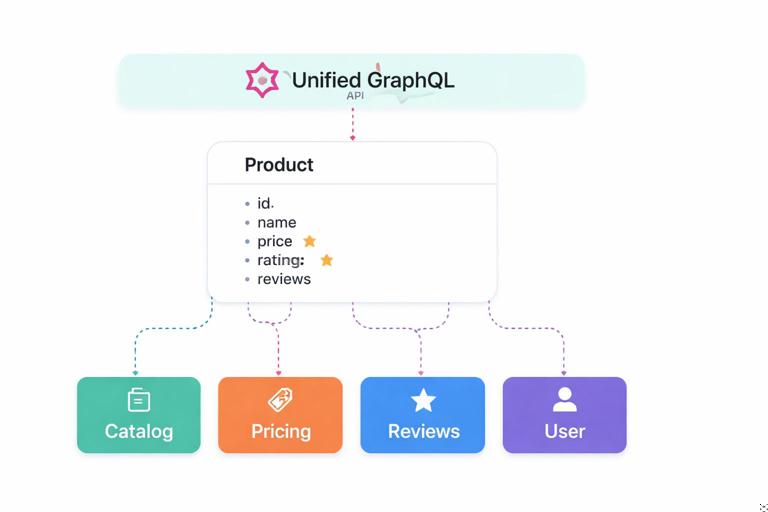

Schema composition: designing boundaries for multi-source backends

Flexible backends often aggregate data from multiple systems: a product catalog service, pricing service, reviews service, and user service. Schema-first design helps you define a unified graph that hides these boundaries from clients. The key is to keep types cohesive and to avoid forcing clients to know which backend owns which field.

One practical technique is to define types around the domain and annotate (in your internal design docs or schema comments) which subsystem owns each field. Then implement resolvers that fetch from the appropriate source. If you later move a field to a different service, the schema does not change.

type Product { id: ID! name: String! price: Money! reviewSummary: ReviewSummary!}type ReviewSummary { averageRating: Float! count: Int!}In implementation, price might come from pricing, and reviewSummary from reviews, but the schema remains a stable contract. Schema-first design pushes you to decide the shape first and then solve the data-fetching problem behind it.

Deprecation and safe evolution without versioning

Schema-first APIs evolve by adding fields and deprecating old ones. Deprecation is a contract-level signal to clients and tooling. When you deprecate, provide a reason and a replacement field when possible. Keep the old field working until usage drops to an acceptable level.

type Product { id: ID! name: String! sku: String! @deprecated(reason: "Use inventorySku for warehouse operations; sku remains for storefront display") inventorySku: String!}Avoid removing fields abruptly. If you must change behavior, consider adding a new field with the new semantics and deprecating the old one. Schema-first design makes these changes explicit and reviewable.

Practical schema-first iteration: a mini design exercise

Step 1: Start with a thin vertical slice

Pick one end-to-end use case and design only what is needed. For example: “Product detail page” might need product name, price, availability, and a few reviews. Draft the schema for those fields first, even if you know more will come later.

type Query { product(id: ID!): Product}type Product { id: ID! name: String! price: Money! availability: ProductAvailability! topReviews(first: Int = 3): [Review!]!}type Review { id: ID! rating: Int! title: String! body: String author: ReviewAuthor!}type ReviewAuthor { displayName: String!}enum ProductAvailability { IN_STOCK OUT_OF_STOCK PREORDER}This slice is intentionally small. It gives clients something usable quickly and provides a foundation for later expansion.

Step 2: Add extensibility points where change is likely

Identify areas likely to change: availability rules, pricing formats, review author details. Instead of exposing raw fields that might need rework, introduce types that can grow. For example, ReviewAuthor can later add avatarUrl or profileUrl without changing existing queries.

Similarly, if pricing might include discounts, taxes, or price ranges, design Money and possibly a Price object that can evolve.

type Price { current: Money! original: Money discountPercent: Int}type Product { id: ID! name: String! price: Price!}Clients that only need current can query it, while others can opt into additional fields later.

Step 3: Validate the schema and run a contract review

Before implementing resolvers, validate the schema with a linter and run a contract review with stakeholders. Check naming consistency (singular vs plural), argument naming, nullability, and whether types reflect business language. Ask: “Can we add a new field here without breaking anyone?” and “Does this expose internal details we might regret?”

Also check for accidental coupling: for example, returning database IDs that might change, or exposing internal status codes. Schema-first design is the moment to correct these issues before they become client dependencies.

Common schema-first pitfalls and how to avoid them

One pitfall is over-modeling: creating too many types too early, which slows iteration. Prefer a thin slice and expand as real use cases appear. Another pitfall is under-modeling: using generic strings everywhere, which makes the schema ambiguous and harder to validate. Use custom scalars and value objects where they add clarity.

A frequent issue is inconsistent list patterns: some fields use offset pagination, others use cursors, others return raw arrays with no arguments. Standardize early. Another issue is careless nullability: marking fields non-null because “it should be there,” then discovering real-world cases where it is missing. Be honest about guarantees and use non-null only when you can enforce it.

Finally, avoid designing the schema as a mirror of internal services. If clients must know which service owns which field, your schema is not acting as a unified graph. Keep the schema domain-focused and let resolvers handle composition behind the scenes.