Why query complexity and depth controls matter

GraphQL gives clients the power to shape responses, but that same flexibility can be abused. A single request can ask for deeply nested fields, wide selections with many siblings, or expensive fields repeated across many nodes. Even if each resolver is “correct,” the combined work can overwhelm CPU, memory, downstream services, or databases. Query complexity limits and depth controls are defensive mechanisms that constrain the maximum work a single operation can trigger, reducing the risk of denial-of-service patterns and protecting shared infrastructure.

Two abuse patterns show up frequently in production. The first is “deep nesting,” where a query walks relationships many levels down, causing repeated resolver execution and large response payloads. The second is “wide fan-out,” where a query requests many expensive fields across a large list of nodes, multiplying cost. Depth controls primarily address deep nesting; complexity controls address both depth and width by assigning a cost model to the operation.

Threat model: what you are defending against

Before implementing limits, define what “abuse” means for your system. Abuse can be malicious (intentional DoS) or accidental (a client developer writes an overly broad query). Typical failure modes include timeouts, memory pressure from large JSON responses, saturation of downstream services, and noisy-neighbor effects where one tenant degrades others. Complexity and depth controls are not a substitute for authentication, authorization, or rate limiting, but they are an important layer that limits per-request blast radius.

GraphQL-specific risk is that the server cannot rely on a fixed endpoint shape. In REST, you can pre-size the work per endpoint; in GraphQL, the work depends on the query document. That is why you need request-time analysis of the operation’s structure and a policy that decides whether to execute it.

Depth limiting: controlling nested traversal

Depth limiting sets a maximum nesting level for a query. Depth is usually measured as the longest path from the operation root to a leaf field, counting field selections along the way. For example, a query that requests viewer { organization { teams { members { profile { avatarUrl } } } } } has a depth equal to the number of nested selection steps. Depth limits are simple to reason about and cheap to compute, making them a good baseline control.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

How depth is calculated (and common pitfalls)

Depth calculation must account for fragments and inline fragments, because attackers can hide nesting inside fragments. The depth algorithm should traverse the parsed GraphQL AST after validation, expanding fragment spreads and tracking the maximum depth across all possible type conditions. Another pitfall is counting introspection fields; many teams allow introspection only in non-production, or they apply separate limits to introspection queries.

Depth alone does not capture “width.” A query can be shallow but still expensive by requesting many fields or large lists. That is why depth limiting is best paired with complexity scoring.

Step-by-step: implementing depth limiting

Step 1: Choose a depth policy. Start with a conservative default such as 8–12 for general APIs, then adjust based on real client needs. If your schema has naturally deep hierarchies (for example, nested comments), you may need a higher limit but should pair it with stronger complexity scoring.

Step 2: Parse and validate the query. Depth checks should run after parsing and basic validation so you can reliably traverse selections and fragments.

Step 3: Traverse the AST and compute maximum depth. Track current depth as you descend into selection sets, and update a global maximum. When encountering fragment spreads, resolve them from the document’s fragment definitions and traverse their selection sets as if they were inlined.

Step 4: Reject or require special handling when the limit is exceeded. The server should return a client-safe error indicating the query is too deep, ideally including the allowed maximum and the measured depth.

Step 5: Add observability. Log the measured depth, operation name, client identifier, and whether it was blocked. This helps tune limits and detect abuse patterns.

// Pseudocode: depth calculation over a GraphQL AST (language-agnostic) function maxDepth(operation, fragments): visitedFragments = set() function walk(selectionSet, depth): maxSeen = depth for selection in selectionSet: if selection is Field: if selection has selectionSet: maxSeen = max(maxSeen, walk(selection.selectionSet, depth + 1)) else: maxSeen = max(maxSeen, depth + 1) if selection is InlineFragment: maxSeen = max(maxSeen, walk(selection.selectionSet, depth + 1)) if selection is FragmentSpread: name = selection.name if name not in visitedFragments: visitedFragments.add(name) maxSeen = max(maxSeen, walk(fragments[name].selectionSet, depth + 1)) return maxSeen return walk(operation.selectionSet, 0)Query complexity scoring: limiting total work

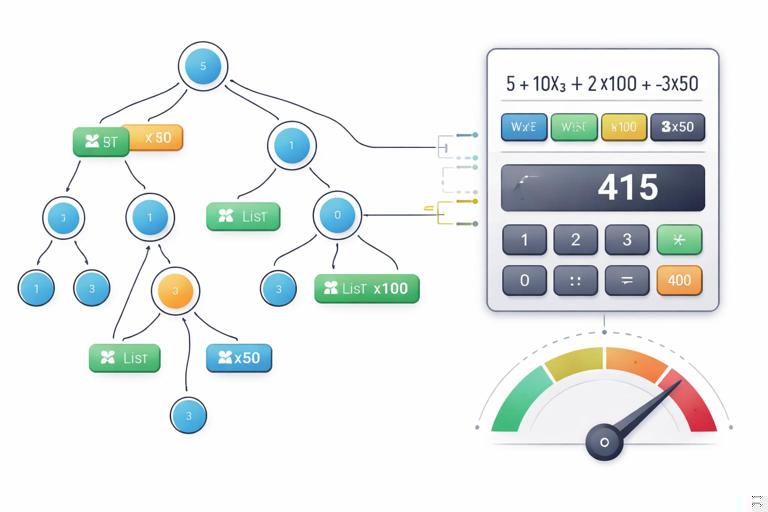

Complexity scoring assigns a numeric “cost” to a query and rejects queries whose cost exceeds a threshold. Unlike depth, complexity can model expensive fields, list multipliers, and repeated work. The goal is not to predict exact runtime, but to approximate relative cost and prevent pathological queries from executing.

A practical complexity model has three ingredients: a base cost per field, multipliers for list fields, and custom costs for known expensive resolvers. For example, a scalar field might cost 1, a field that triggers a downstream call might cost 10, and a list field might multiply the cost of its children by an estimated item count.

Understanding “width” and list multipliers

Consider a query that requests 100 items and for each item requests 10 fields, including two expensive fields. Even with batching and caching, the server still has to compute and serialize a large response. Complexity scoring captures this by multiplying child costs by the expected list size. The list size can be derived from pagination arguments (for example, first), or from a default estimate when the size is unknown.

Because list size is often client-controlled, complexity scoring should treat missing limits as risky. If a list field supports pagination arguments, enforce that a limit argument is present and bounded, and use that bound in the complexity calculation. If a list field does not have a limit argument, consider assigning it a high default multiplier or disallowing it for untrusted clients.

Step-by-step: building a complexity model

Step 1: Define a default cost per field. Many teams start with 1 for most fields. This ensures that “wide” queries still accumulate cost even if no field is marked expensive.

Step 2: Identify expensive fields and assign custom costs. Examples include fields that call external services, perform full-text search, compute aggregations, or generate signed URLs. Assign higher costs to these fields to reflect their impact.

Step 3: Define list multipliers. For list-returning fields, multiply the complexity of the child selection set by an estimated item count. Prefer using explicit pagination arguments (like first, limit, or pageSize) and cap them at a maximum.

Step 4: Handle fragments and inline fragments. Complexity must include costs from all selections, including those introduced via fragments. For inline fragments on unions/interfaces, include the maximum possible cost across type conditions or sum them depending on execution semantics. A conservative approach is to take the maximum per possible runtime type to avoid over-penalizing polymorphic selections, but if your execution can resolve multiple types in a list, you may need to account for that multiplicative effect.

Step 5: Set thresholds per client tier. A public API might allow a lower maximum complexity than an internal trusted client. If you have multi-tenant traffic, consider per-tenant thresholds and combine them with rate limits.

Step 6: Enforce at request time. Compute complexity before execution and reject queries above the threshold with a clear error message. Include the computed score and the allowed maximum to help client developers adjust.

// Pseudocode: complexity scoring with list multipliers function complexity(operation, fragments, schemaCostConfig, variables): function fieldCost(fieldName, parentType): return schemaCostConfig.customCost[parentType + '.' + fieldName] ?? schemaCostConfig.defaultFieldCost function listMultiplier(fieldNode, parentType): // Example: use 'first' argument if present, else default estimate if fieldNode has argument 'first': n = valueOf(fieldNode.argument('first'), variables) return clamp(n, 0, schemaCostConfig.maxPageSize) return schemaCostConfig.defaultListSizeEstimate function walk(selectionSet, parentType): total = 0 for selection in selectionSet: if selection is Field: base = fieldCost(selection.name, parentType) if selection returns List: mult = listMultiplier(selection, parentType) child = selection.selectionSet ? walk(selection.selectionSet, selection.returnType) : 0 total += base + mult * child else: child = selection.selectionSet ? walk(selection.selectionSet, selection.returnType) : 0 total += base + child if selection is InlineFragment: total += walk(selection.selectionSet, selection.typeCondition ?? parentType) if selection is FragmentSpread: total += walk(fragments[selection.name].selectionSet, parentType) return total return walk(operation.selectionSet, operation.rootType)Depth vs complexity: choosing the right combination

Depth limits are easy and effective against recursive nesting patterns, but they do not stop shallow, wide queries. Complexity scoring is more flexible but requires a cost model and ongoing tuning. In practice, use both: depth as a hard guardrail and complexity as the main control for overall work. If you must choose one, complexity provides broader coverage, but depth is often a simpler first step and can be implemented quickly.

Also consider response size as a separate axis. A query might have acceptable complexity but still produce a huge payload (for example, many large strings). Some teams enforce a maximum response size or maximum nodes returned. Response size limits are not strictly “complexity,” but they complement it by protecting memory and bandwidth.

Handling variables, aliases, and repeated fields

Complexity analysis must evaluate argument values after variable substitution. Attackers can hide large list sizes in variables, so compute multipliers using resolved variable values. Aliases can also be used to request the same field multiple times with different arguments; complexity should count each occurrence because execution work and response size increase.

Another subtle case is repeated selections across fragments. Even if the same field appears multiple times, GraphQL execution merges identical fields at the same response path, but aliases and differing arguments prevent merging. A safe approach is to compute complexity on the normalized selection set after validation and field collection, or to conservatively count occurrences in the AST while still accounting for merging rules where applicable.

Special treatment for expensive operations

Some fields are inherently heavy regardless of selection shape: search, analytics, exports, or fields that trigger complex authorization checks. For these, complexity scoring should incorporate fixed surcharges and sometimes additional constraints. For example, a search field might require a minimum query length, enforce a maximum page size, and have a high base cost. An export field might be disallowed in synchronous GraphQL and instead return a job identifier.

Another pattern is “cost by argument.” A field that accepts a list of IDs might have cost proportional to the number of IDs. Similarly, a field that accepts a time range might have cost proportional to the range length. Complexity scoring can incorporate these by reading argument values and applying a formula.

// Example: cost-by-argument for a field that accepts ids: [ID!] function idsCost(args, variables): ids = valueOf(args['ids'], variables) return 1 + 2 * length(ids) // base + per-id costPer-operation and per-field policies

Not all operations are equal. You may want different limits for queries vs mutations, or for specific operation names. For example, mutations that write data might be shallow but still expensive due to validation and side effects; you can assign higher base costs to mutation root fields or apply separate thresholds.

Per-field policies can also include hard caps. A list field might require first and reject requests without it. Another field might disallow nested selections beyond a certain depth under that field (a “local depth limit”), which is useful when a particular subtree is risky.

Implementation patterns in common GraphQL servers

Most GraphQL servers allow request middleware or validation rules that run before execution. Depth and complexity checks fit naturally as validation rules: parse the document, validate it, compute depth/complexity, and either proceed or return an error. This approach ensures you block abusive queries before resolvers run and before any downstream calls are made.

When implementing, keep the computation fast and deterministic. Avoid any network calls during analysis. Use cached schema metadata (for example, which fields are lists, custom costs, and maximum page sizes). If you support persisted operations, store precomputed depth/complexity for each operation hash and only recompute when variables affect multipliers.

Tuning limits with real traffic

Setting the right thresholds is an iterative process. Start by measuring depth and complexity for real client operations in a “report-only” mode where you compute scores but do not block. Collect distributions by client, operation name, and endpoint. Then choose thresholds that block outliers while allowing normal traffic.

When you begin enforcing, provide actionable errors. A generic “query too complex” message frustrates clients. Include the computed score, the maximum allowed, and optionally which field contributed most to the cost. Some teams also expose a developer-only header or extension field that returns the computed complexity for debugging.

Operational safeguards that complement complexity controls

Complexity and depth limits work best alongside timeouts and concurrency limits at the GraphQL server layer. Even well-scored queries can become slow if downstream services degrade. Enforce per-request timeouts, limit concurrent resolver execution where appropriate, and apply circuit breakers for unstable dependencies. These are not replacements for complexity controls, but they reduce the impact of unpredictable runtime conditions.

Finally, treat limits as part of an abuse-prevention policy. Different clients may have different trust levels. Combine complexity thresholds with client identification, authentication context, and tenant-level quotas so that a single client cannot consume disproportionate resources.