Why scope definition matters to the schedule

A construction schedule is only as reliable as the scope it represents. “Scope definition” means translating what the project must deliver (and what it explicitly will not deliver) into a structured set of work that can be planned, sequenced, resourced, and tracked. If scope is vague, the schedule becomes a collection of guesses: activities are missing, durations are optimistic, dependencies are wrong, and progress reporting becomes subjective.

Scheduling assumptions are the companion to scope definition. They are the explicit statements you make to fill in what is not yet fully known (or what is known but not yet documented) so that a workable schedule can be produced. Assumptions are not excuses; they are placeholders that must be visible, testable, and updated as the project develops.

In practice, scope definition answers “What work exists?” and scheduling assumptions answer “Under what conditions will we perform that work?” Both must be documented and controlled so that schedule changes can be traced to a cause (scope change, assumption invalidation, or performance issue).

Scope definition: what it is (and what it is not)

Scope definition in scheduling terms

For scheduling, scope definition is the process of converting project requirements, drawings, specifications, and stakeholder expectations into a complete list of deliverables and work packages that can be represented in the schedule. The output is not just a narrative; it is a structured scope model that supports:

- Activity identification (what tasks must be performed)

- Work breakdown alignment (how tasks roll up to areas, systems, or phases)

- Responsibility assignment (who performs and who approves)

- Interfaces (where trades and vendors hand off work)

- Acceptance criteria (what “done” means for each deliverable)

What scope definition is not

It is not a full estimate. You may use estimating data, but scope definition focuses on completeness and boundaries, not pricing.

Continue in our app.- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

It is not a design exercise. You can schedule with incomplete design, but you must state assumptions and identify design-dependent work.

It is not a contract rewrite. Contract language informs scope, but the schedule needs operational work packages and measurable deliverables.

Scheduling assumptions: the “rules of the game”

Scheduling assumptions are the conditions you assume to be true when building the schedule. They typically cover calendars, access, productivity, procurement lead times, permitting, inspections, owner decisions, and constraints such as noise ordinances or limited laydown space.

Assumptions should be written so they can be verified. A good assumption is specific, measurable, and tied to a schedule element. A weak assumption is vague and cannot be tested.

Examples of strong vs. weak assumptions

Weak: “Materials will arrive on time.”

Strong: “Curtain wall fabrication lead time assumed 14 weeks from approved shop drawings; delivery in two shipments (floors 2–6, floors 7–12) with 5 working days between shipments.”

Weak: “Inspections will be available.”

Strong: “City framing inspections assumed available within 48 hours of request; inspection requests submitted by 10:00 a.m. the day prior.”

Step-by-step: define scope so it can be scheduled

Step 1: Gather scope inputs and identify the “scope sources of truth”

Start by listing the documents and stakeholders that define scope. Typical inputs include drawings, specifications, addenda, owner standards, geotechnical reports, utility letters, contract exhibits, and vendor proposals. The key is to identify which documents govern when conflicts occur and which items are still pending.

Create a simple register of scope inputs with version/date and status (issued for bid, issued for construction, preliminary, etc.). This prevents building a schedule on outdated information.

Step 2: Define project boundaries (in-scope vs. out-of-scope)

Write explicit boundaries that affect schedule logic. Boundaries should be stated in operational terms. Examples:

- Sitework includes demolition of existing slab but excludes offsite roadway improvements beyond property line.

- Owner provides furniture procurement; contractor provides receiving coordination and installation labor only if owner issues a separate directive.

- Commissioning includes HVAC and controls; excludes process equipment commissioning by vendor.

These boundaries prevent “phantom activities” (work you are assumed to do but is not in your scope) and “missing activities” (work someone expects but no one planned).

Step 3: Break scope into deliverables and work packages

Convert the scope into a structured list that can be scheduled. A practical approach is to break by:

- Area (building A, building B, floors, zones)

- System (structural, envelope, MEP, fire protection, finishes)

- Phase (demo, foundations, superstructure, rough-in, close-in, commissioning)

Each work package should be small enough to plan and track, but not so small that the schedule becomes unmanageable. A common test: can the superintendent or trade foreman reliably report percent complete and forecast remaining duration for the package?

Step 4: Define “done” for each deliverable

Scheduling depends on clear completion criteria. For each deliverable, define what must be true for it to be considered complete and ready for successor work. Examples:

- “Slab on grade complete” = rebar inspected, concrete placed, cured to specified strength, sawcut complete, layout control points re-established.

- “Electrical rough-in complete in Zone 3” = conduit and boxes installed, pull strings in place, above-ceiling inspection passed, sleeves/firestopping installed where required for rough-in stage.

Without this, activities finish “on paper” but successors cannot start, creating hidden float consumption and rework.

Step 5: Identify interfaces and handoffs

Interfaces are where schedule risk concentrates: trade-to-trade handoffs, vendor-to-field transitions, and owner/authority approvals. Document them explicitly. Examples:

- Steel erection handoff to metal deck and shear studs

- MEP rough-in handoff to drywall close-in

- Controls vendor handoff to TAB and commissioning

- Utility company energization handoff to startup

For each interface, define prerequisites, responsible party, and required lead time (submittals, inspections, access).

Step 6: Translate work packages into schedule activities

Now convert work packages into activities with measurable outputs. Avoid activities that are too broad (“MEP rough-in”) unless they are broken by area/zone or by system. A practical pattern is:

- Prep (layout, mobilize, material staging)

- Install (production work)

- Inspect/test (hold points)

- Close (punch, documentation)

Keep activity names action-oriented and specific: “Install duct mains Level 4 East,” “Pressure test domestic water risers,” “Insulate chilled water mains Level 4,” etc.

Step-by-step: build and manage scheduling assumptions

Step 1: Create an assumptions log tied to schedule elements

Maintain a scheduling assumptions log (a simple table works) with fields such as: assumption ID, description, category, impacted activities/WBS, owner (who validates), date created, target validation date, status (open/validated/invalid), and schedule impact if invalid.

Link assumptions to the schedule by referencing activity IDs or WBS codes. This makes it possible to quantify impact when an assumption changes.

Step 2: Define the project calendar assumptions

Calendar assumptions set the baseline for durations and productivity. Document:

- Working days per week (e.g., Mon–Fri)

- Working hours per day (e.g., 7:00 a.m.–3:30 p.m.)

- Planned overtime rules (if any)

- Holiday shutdowns

- Weather allowances (if used) and how they are applied

Example assumption: “Concrete pours permitted Saturdays with prior notice; all other trades limited to Mon–Fri due to local ordinance.” This directly affects sequencing and achievable durations.

Step 3: Access, logistics, and constraints assumptions

Construction is often constrained by access and logistics more than by pure task duration. Document assumptions such as:

- Laydown area availability and size

- Crane availability windows and swing restrictions

- Elevator/hoist commissioning date for material movement

- Floor loading limits and material storage rules

- Noise/vibration restrictions and allowable work hours

These assumptions should be reflected in logic (e.g., hoist required before drywall delivery to upper floors) rather than left as informal notes.

Step 4: Procurement and submittal assumptions

Procurement is a frequent driver of critical path. Assumptions should cover:

- Submittal preparation durations by trade

- Review cycles (contractor review, designer review, resubmittals)

- Fabrication lead times after approval

- Shipping durations and delivery constraints

- Mockups and first-article approvals

Example: “Generator submittal: 10 working days contractor review + 15 working days engineer review + 10 working days resubmittal review; fabrication 20 weeks after approval; startup requires factory rep with 3-week notice.” Each component becomes schedule activities and constraints.

Step 5: Permitting, inspections, and authority assumptions

Authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs) can introduce hard constraints. Document:

- Permit issuance durations and prerequisites

- Inspection request lead times

- Special inspections requirements (who provides, when scheduled)

- Utility company timelines (service application, transformer set, meter install)

- Fire alarm acceptance testing and fire marshal availability

Where possible, convert these into activities with predecessors and successors rather than fixed dates, so the schedule remains logic-driven.

Step 6: Productivity and crew assumptions (used carefully)

Productivity assumptions should be explicit and based on realistic constraints. Examples:

- “Drywall: 2 crews, each 4 installers, producing 8,000 SF board/day per crew in open areas; reduce by 30% in congested MEP corridors.”

- “Concrete cycle: 5-day cycle per bay assuming one forming crew and one rebar crew; inspections available within 24 hours.”

If productivity is uncertain, treat it as a risk and consider range-based planning (best/most likely/worst) for internal forecasting, while keeping the baseline schedule consistent with agreed assumptions.

How scope and assumptions show up inside the CPM schedule

Make scope completeness visible through the WBS

A well-structured WBS is a scope map. Organize the schedule so that every major deliverable has a corresponding branch. If a deliverable exists in the drawings/specs but not in the WBS, it is a red flag that the schedule may be incomplete.

Use milestones to represent scope boundaries and approvals

Milestones are effective for scope control when they represent objective events, such as:

- “Permit issued”

- “Structural steel complete”

- “Building dried-in”

- “Permanent power available”

- “Substantial completion inspection”

Each milestone should have clear entry criteria and should not be used as a placeholder for missing logic.

Convert assumptions into logic, not just notes

If an assumption affects sequence, represent it with relationships and activities. Example: if you assume “Area A available for fit-out after tenant vacates,” create an activity “Tenant vacates Area A” (even if it is owner-driven) and tie it as a predecessor to demolition or build-out. This makes the dependency visible and reportable.

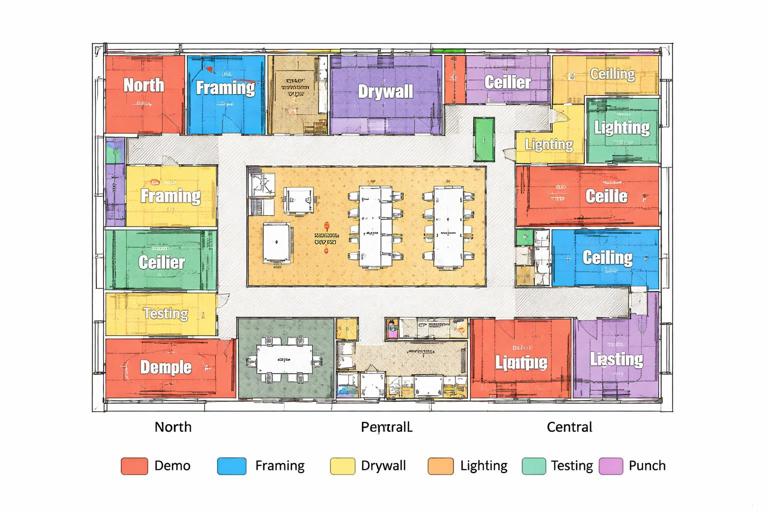

Practical example: defining scope and assumptions for a small commercial fit-out

Scope definition snapshot

Project: 12,000 SF office fit-out on one floor of an occupied building. Key deliverables include selective demolition, new partitions, MEP modifications, finishes, and commissioning of modified systems.

- In-scope: demo of existing partitions in Suite 400, new conference rooms, new lighting controls, HVAC rebalancing, fire alarm device relocations, patch/paint, carpet tile.

- Out-of-scope: base building chiller plant work, elevator modernization, furniture procurement (owner-provided).

Work packages that schedule well

- Demo by zone (north, central, south)

- Framing and above-ceiling rough-in by zone

- Drywall hang/tape by zone

- Ceiling grid and tile by zone

- Lighting fixtures and controls by zone

- Test/inspect: above-ceiling inspection, fire alarm testing, HVAC TAB

- Punch and owner walkthrough

Scheduling assumptions snapshot

- Work hours: nights only (6:00 p.m.–2:30 a.m.) due to occupied building; weekends allowed with 72-hour notice.

- Noise: coring limited to weekends.

- Access: freight elevator reserved 6:00 p.m.–7:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m.–2:30 a.m. only.

- Inspections: building engineer walkthrough required before ceiling close-in; assumed available within 24 hours of request.

- Materials: lighting fixtures lead time assumed 6 weeks after approved submittals; controls gear 8 weeks.

Notice how these assumptions directly shape the schedule: night shift reduces productivity, elevator windows constrain material flow, and weekend-only coring creates a hard sequence constraint for MEP penetrations.

Common scope-definition gaps that break schedules (and how to prevent them)

Gap 1: Missing temporary works and enabling activities

Schedules often omit enabling work like temporary power, temporary lighting, protection, scaffolding, shoring, and dust control. Prevent this by adding a “temporary works” scope checklist during scope breakdown and ensuring each item is assigned to a responsible party.

Gap 2: Under-defined closeout and turnover scope

Turnover is not a single event; it includes testing, documentation, training, O&M manuals, as-builts, and punchlist cycles. Define these deliverables early and create activities for them with realistic durations and dependencies (e.g., O&M manuals depend on approved submittals and vendor data).

Gap 3: Commissioning and startup boundaries unclear

When it is unclear who performs startup, who provides factory reps, and what prerequisites exist (permanent power, controls integration, TAB complete), schedules become optimistic. Define commissioning scope by system and include prerequisite milestones such as “controls point-to-point complete” and “TAB complete” before functional testing.

Gap 4: Owner decisions treated as “instant”

Selections and approvals (finishes, equipment, signage) consume time and can be on the critical path. Treat them as scope-driven activities with durations and required dates, and document the assumption for review turnaround.

How to validate scope and assumptions with the project team

Run a scope-to-schedule workshop

Hold a structured session with superintendent, key subcontractors, and project management. Use the WBS as the agenda and confirm:

- Every deliverable is represented

- Handoffs are understood

- Completion criteria are agreed

- Constraints are captured as assumptions or activities

Use “challenge questions” to expose hidden scope

- What must be in place before you can start this activity?

- What inspections or hold points stop you from proceeding?

- What materials have the longest lead times?

- What work happens in parallel that could create congestion?

- What rework loops are common (e.g., above-ceiling inspection failures)?

Document the answers as either scope items (new activities/work packages) or assumptions (conditions that must hold true).

Documenting scope and assumptions inside the schedule package

Minimum documentation set

To keep scope and assumptions from becoming tribal knowledge, include them in the schedule narrative or schedule basis document. At minimum, provide:

- Scope summary and explicit exclusions

- WBS description and how areas/systems are organized

- Key milestones and their definitions

- Calendars and work-hour assumptions

- Procurement/submittal lead time assumptions

- Constraints and access assumptions

- Inspection/permit assumptions

- List of open assumptions with validation dates

Example: assumptions log format (template)

ID | Category | Assumption | Impacts (WBS/Activities) | Owner | Validate By | Status | If Invalid, Likely Impact

A-01 | Calendar | 5x8 workweek, no Sat except concrete | All structural concrete | PM | 2026-02-01 | Open | +10% duration on pours if Sat not allowed

A-02 | Procurement | AHU lead time 16 weeks after approved submittal | MEP procurement, startup | MEP Sub | 2026-01-20 | Open | Delays commissioning milestone

A-03 | Inspections | Framing inspection within 48 hrs of request | Interior close-in | Super | 2026-02-10 | Open | Ceiling close-in delayed, impacts finishesThis format forces clarity: who owns validation, when it must be confirmed, and what the schedule consequence is.

Managing changes: distinguishing scope change from assumption failure

When the schedule shifts, you need to identify whether the cause is:

- Scope change: new deliverables added, exclusions removed, design changes that add work.

- Assumption invalidation: a condition you planned on is not true (e.g., inspection turnaround becomes 5 days instead of 2).

- Performance variance: the plan was sound but execution underperformed (productivity, coordination, rework).

To make this distinction, keep your assumptions log current and tie it to schedule updates. When an assumption changes, record the date it was invalidated and update the affected activities (durations, logic, or calendars). This creates a defensible record of why the schedule changed and what actions are required (mitigation, resequencing, added crews, or formal change management).