Why anchors, targets, and concession plans matter in non‑sales negotiations

In non‑sales roles, you negotiate constantly: project scope with a partner team, timelines with engineering, budget with finance, hiring packages with candidates, service levels with vendors, or priorities with leadership. These negotiations often feel “soft” because there is no price tag on a product, but they still involve value, trade‑offs, and scarce resources. Anchors, targets, and concession planning give you a concrete structure for making offers, responding to pushback, and trading value without drifting into reactive decisions.

Think of these three elements as a navigation system:

- Anchor: the first credible reference point you put on the table (or the reference point you must respond to if the other side anchors first).

- Target: the outcome you are aiming to achieve (your “success point”).

- Concession plan: the sequence of conditional moves you are willing to make to reach agreement while protecting what matters most.

Used together, they prevent common problems: conceding too quickly, negotiating against yourself, accepting vague promises, or ending with an agreement that looks fine in the meeting but fails in execution.

Anchors: setting the reference point without losing credibility

What an anchor is (and what it is not)

An anchor is a specific starting point that shapes the rest of the negotiation. It can be a number (budget, headcount, timeline), a range, a policy reference, a benchmark, or a concrete proposal package. It is not a random extreme demand. A strong anchor is ambitious but defensible, and it is presented with a rationale that makes it hard to dismiss.

In non‑sales contexts, anchors often appear as:

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

- Timeline anchors: “We can commit to a launch window of May 6–May 20 if we freeze scope by March 15.”

- Scope anchors: “Phase 1 includes A, B, and C; D and E are Phase 2.”

- Resource anchors: “This initiative needs 0.5 FTE from data engineering for six weeks.”

- Service level anchors: “We need a 99.9% uptime SLA and 24-hour response for P1 incidents.”

- Decision process anchors: “We’ll evaluate vendors using security, total cost, and implementation time; final decision by April 10.”

Why anchoring works

Anchoring works because people use the first concrete figure or proposal as a reference point, even when they know it is negotiable. In practice, the anchor influences what feels “reasonable,” how far concessions seem to go, and where the final agreement lands.

When to anchor first vs. wait

Anchoring first can be advantageous when you have strong information and can justify your proposal. Waiting can be better when the other side may reveal constraints or offer more favorable terms than you expected.

- Anchor first when: you have benchmarks, you understand the other side’s constraints, you can defend your ask, and you want to frame the zone of discussion.

- Let them anchor when: you suspect they may over-offer (e.g., vendor discounts, internal team capacity), you lack data, or you want to learn their priorities before committing to a position.

In many internal negotiations, the other side will implicitly anchor with statements like “This should be quick” or “We can’t allocate anyone.” Treat these as anchors even if they are not numeric.

How to craft a credible anchor

Use a three-part structure: proposal + rationale + verification question.

- Proposal: a specific offer or request.

- Rationale: objective criteria, benchmarks, workload estimates, risk reduction, or precedent.

- Verification question: invites engagement and surfaces constraints.

Example (cross-functional timeline):

“To hit the compliance deadline, I’m proposing we target a May 10 launch with a scope freeze on March 15. That gives engineering two full sprints for build and one sprint for stabilization, which matches our last release cycle. What constraints would prevent us from committing to that freeze date?”

Anchoring with ranges (and when not to)

Ranges can be useful when uncertainty is real, but they can also weaken your position if the other side immediately pushes to the favorable end of your range. If you use a range, make it:

- Narrow enough to be meaningful.

- Directional (your preferred end is clear).

- Conditional (tied to assumptions).

Example (vendor implementation): “Implementation is 6–8 weeks assuming we get security approval within 10 business days; if approval takes longer, the timeline shifts accordingly.”

How to respond when the other side anchors first

If the other side anchors with an unfavorable number or position, avoid immediate countering without context. Use a sequence that buys time and re-centers on criteria:

- Label: “I hear you’re targeting a two-week turnaround.”

- Question: “What’s driving that timeline?”

- Re-anchor with criteria: “Given testing requirements and our current sprint commitments, a realistic window is four to six weeks unless we reduce scope or add resources.”

- Offer options: “We can do two weeks if we limit to A and B, or we can keep full scope with a later date.”

Targets: defining what “success” looks like in measurable terms

Targets vs. anchors

Your target is the outcome you want to land on after negotiation. Your anchor is where you start. Confusing the two leads to either timid anchors (starting at your target) or unrealistic targets (anchoring with wishful thinking).

Targets should be:

- Specific: measurable and observable.

- Multi-dimensional: not only one variable (e.g., not just timeline, but timeline + scope + quality + resourcing).

- Documentable: can be written into an agreement, ticket, project plan, or email recap.

Building a target as a “package”

In non‑sales negotiations, the best targets are often packages rather than single points. A package ties together multiple variables so you can trade across them.

Example (internal service request):

- Target package: “Data team delivers dashboard v1 by April 12, includes metrics X/Y/Z, refresh daily, with one enablement session for stakeholders.”

- Why it works: it clarifies deliverable, date, and support, reducing later disputes.

Example (vendor contract):

- Target package: “Annual cost under $120k, 99.9% uptime, SSO included, 30-day termination for cause, implementation support included.”

Setting targets under uncertainty

When you cannot know the exact right target, define a target with assumptions and triggers. This keeps you from committing to a fixed point that becomes unrealistic.

- Assumption-based target: “Target is a 6-week delivery assuming we receive final requirements by Friday.”

- Trigger-based adjustment: “If requirements change after sign-off, we re-estimate and adjust timeline.”

Target ladders: primary, secondary, and stretch

Instead of one target, create a ladder:

- Stretch target: best realistic outcome.

- Primary target: what you expect to achieve with solid negotiation.

- Secondary target: still acceptable, but requires compensating gains elsewhere.

Example (headcount request):

- Stretch: 1.0 FTE hire in Q2.

- Primary: 0.5 FTE contractor for 6 months starting Q2.

- Secondary: shared resource 0.25 FTE plus tooling budget to automate part of the workload.

This ladder makes it easier to stay calm when you can’t get the ideal outcome; you already know what “acceptable with trade-offs” looks like.

Concession planning: trading value deliberately instead of giving it away

What a concession plan is

A concession plan is a pre-decided map of what you can give, in what order, and under what conditions. It prevents “on-the-spot generosity” driven by discomfort, urgency, or pressure from senior stakeholders.

Concessions are not only about money. In non‑sales roles, common concessions include:

- Reducing scope or features

- Changing delivery dates

- Adjusting quality thresholds (carefully)

- Providing additional support or training

- Changing reporting cadence or governance

- Offering references, case studies, or internal visibility (for vendors/partners)

- Agreeing to a pilot before a full rollout

Principles of effective concessions

- Concede slowly: small steps signal that value is real.

- Concede conditionally: “If we do X, then we need Y.”

- Concede on lower-priority items first: protect what matters most.

- Make concessions visible: name them explicitly so they are recognized.

- Ask for something every time: even small reciprocation maintains balance.

Step-by-step: building a concession plan

Step 1: List negotiable variables (not just the obvious one)

Write down all variables you could adjust. For a project negotiation, that might include scope, timeline, staffing, dependencies, acceptance criteria, escalation path, and meeting load.

Example list (cross-functional project):

- Scope items A/B/C/D

- Delivery date

- Number of review cycles

- Definition of done

- Who provides test data

- On-call support after launch

- Reporting cadence

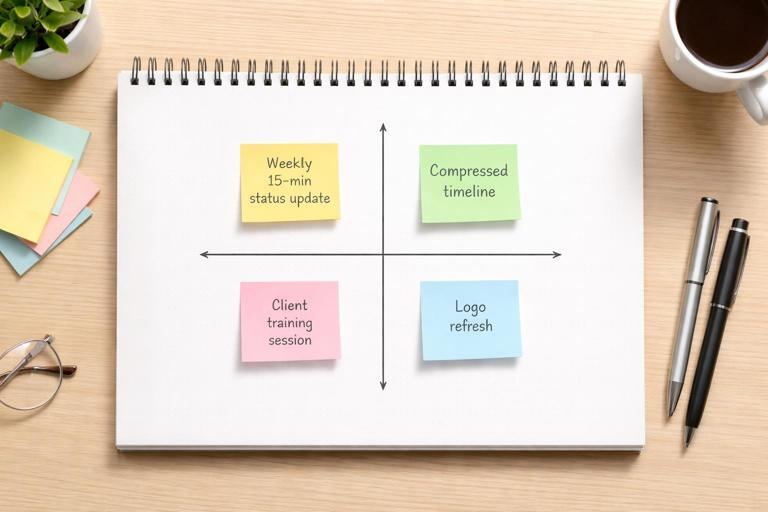

Step 2: Rank variables by cost-to-you and value-to-them

Create a simple 2x2 in your notes: low/high cost to you and low/high value to them. Your best concessions are typically low cost to you, high value to them.

Example: Offering a weekly 15-minute status update might be low cost to you but high value to a stakeholder who fears surprises. Agreeing to a compressed timeline might be high cost to you and high value to them; that should require significant reciprocity.

Step 3: Pre-plan 3–5 concession moves

Define a sequence from least costly to most costly. Each move should be paired with a “get.”

Example (vendor negotiation):

- Move 1: You offer a longer contract term. Get: lower annual price.

- Move 2: You agree to be a reference after 90 days. Get: implementation support included.

- Move 3: You accept quarterly billing. Get: SSO included at no extra cost.

- Move 4: You accept a narrower SLA for non-critical systems. Get: stronger SLA for critical components.

Step 4: Define “if-then” language for each concession

Write the sentence you will say. This reduces hesitation and prevents accidental giveaways.

- “If we move the deadline up by two weeks, then we’ll need you to provide a dedicated reviewer within 24 hours for approvals.”

- “If we include feature D in Phase 1, then we’ll remove feature B or add one engineer for the sprint.”

- “If we agree to a pilot, then success criteria and decision date need to be defined upfront.”

Step 5: Decide your stopping points and escalation triggers

Your plan should include when you pause and escalate rather than continue conceding. Examples of triggers:

- They ask for a concession that increases risk beyond what you can own.

- They refuse to reciprocate after multiple concessions.

- They introduce new stakeholders late who reopen settled items.

- They demand commitments without clarifying acceptance criteria.

Practical phrasing: “I can’t commit to that in this meeting. I need to validate impact with the team and come back with options by tomorrow.”

Putting it together: anchor-target-concession workflow

Step-by-step workflow you can use before any negotiation meeting

Step 1: Choose your anchor format

Decide whether you will anchor with a single proposal, a package, or an option set.

- Single package: best when you want clarity and you can defend it.

- Option set (2–3 packages): best when you want to show flexibility without conceding. Each option should be acceptable to you, with one clearly preferred.

Example option set (project delivery):

- Option A (preferred): Deliver A/B/C by May 10; freeze scope March 15; stakeholder review within 48 hours.

- Option B: Deliver A/B by April 26; C moves to Phase 2; freeze scope March 8.

- Option C: Deliver A/B/C by April 26; add 1 contractor for 6 weeks funded by requesting team.

Step 2: Write your target as a measurable agreement

Draft the sentence you want to be able to send in a recap email. If you cannot write it clearly, it is not yet a usable target.

Example: “We agreed that Legal will review the updated terms by Wednesday EOD, and we will sign by Friday if no redlines affect liability section 4.”

Step 3: Prepare your first two concessions (and what you’ll ask for)

Do not plan ten concessions; plan the first two or three that are most likely. Overplanning can make you rigid. Underplanning makes you reactive.

Step 4: Decide how you will handle their anchor

Write two neutral questions that uncover rationale:

- “What’s driving that number/timeline?”

- “What would make this workable on your side?”

Write one re-anchoring statement tied to criteria:

“Based on the testing and approval steps required, the realistic range is X–Y unless we change scope or resources.”

Practical examples in common non‑sales scenarios

Example 1: Negotiating a deadline with a partner team

Situation: A partner team asks for a full integration in two weeks.

Your anchor: “We can deliver the integration in five weeks with full testing and monitoring.”

Your rationale: “The work includes API changes, QA, security review, and a staged rollout. The last similar integration took four weeks without security changes.”

Your target: “Four to five weeks with scope A/B, plus agreed test plan and a single point of contact for approvals.”

Concession plan:

- Concession 1 (low cost): Offer a partial delivery in two weeks. If-then: “If you need something in two weeks, then we can deliver read-only data first, and full write capability in week five.”

- Concession 2 (higher cost): Accelerate timeline with added resources. If-then: “If we compress to three weeks, then we need a dedicated engineer from your team to pair daily and you’ll accept reduced monitoring for the first week post-launch.”

Example 2: Negotiating scope with leadership

Situation: Leadership wants “everything” in the next release.

Your anchor: Present a package: “Release includes A/B/C; D/E are Phase 2.”

Your target: “A/B/C shipped with quality gates met and no on-call overload.”

Concession plan:

- Concession 1: Add D if E is removed. If-then: “If we include D, then we need to move E to Phase 2 to keep the date.”

- Concession 2: Keep D and E only if date moves. If-then: “If D and E are both must-have, then the earliest date is two sprints later.”

Key technique: you are not saying “no”; you are trading across variables while keeping the anchor package intact.

Example 3: Negotiating vendor terms without being procurement

Situation: A SaaS vendor anchors with a high annual price and a strict contract.

Your response to their anchor: “Help me understand what’s included in that tier and what flexibility you have for implementation support and SSO.”

Your counter-anchor: “For this to work, we need total annual cost under $120k with SSO included and a 30-day termination for cause.”

Your target: “$110–$120k, SSO included, implementation support included, SLA aligned to criticality.”

Concession plan:

- Concession 1: Offer a longer term for price reduction. If-then: “If we sign a two-year term, then we need the annual price reduced to $115k and SSO included.”

- Concession 2: Accept a narrower SLA for non-critical modules. If-then: “If we accept standard SLA for non-critical modules, then we need premium SLA for the core service at no added cost.”

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

Mistake 1: Anchoring with your target

If you start at what you actually want, you leave no room to negotiate and you invite the other side to push you below your target. Fix: anchor above your target while staying credible, and be ready to justify it with criteria.

Mistake 2: Making “free” concessions to be nice

Unconditional concessions teach the other side that pressure works. Fix: attach conditions. Even small asks (faster approvals, clearer requirements, fewer meetings) create reciprocity.

Mistake 3: Conceding in big jumps

Large jumps signal that your earlier position was inflated or that more movement is available. Fix: plan smaller increments and pause to summarize after each move.

Mistake 4: Negotiating one variable in isolation

Arguing only about timeline or only about scope traps you. Fix: negotiate packages and options so you can trade across variables.

Mistake 5: Forgetting to document the final anchor and concessions

Agreements fail when the negotiated trade-offs are not captured. Fix: recap in writing with specifics: deliverables, dates, owners, acceptance criteria, and what was traded.

Tools you can copy into your notes

Anchor statement template

Proposal: [specific package or number] Rationale: [objective criteria/benchmark/work estimate/risk] Question: [what constraints or assumptions should we validate?]Target package template

Target agreement: By [date], [owner/team] delivers [deliverable] with [scope/quality criteria], assuming [assumptions]. Success is measured by [metric/acceptance test].Concession plan template (3 moves)

Concession 1 (low cost): If we [give], then you [give]. Concession 2 (medium cost): If we [give], then you [give]. Concession 3 (high cost): If we [give], then you [give]. Escalation trigger: If [condition], then pause and escalate to [person/process].