What “Packaging and Shipping” Means in Kubernetes

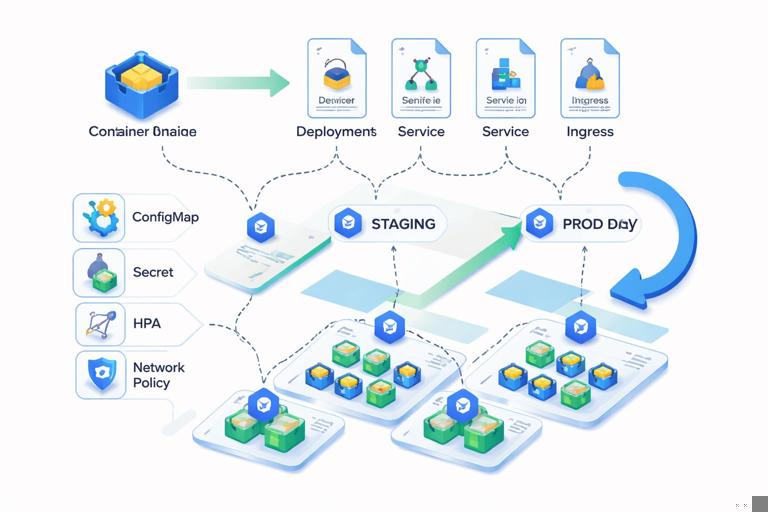

After you already have a container image for your service, “packaging and shipping” is the work of turning that image into a repeatable, configurable, and operable Kubernetes workload. Packaging answers: what Kubernetes objects are needed, how are they parameterized per environment, and how do you version them? Shipping answers: how do those objects get applied to clusters safely and consistently, with promotion across environments and rollback when needed?

In practice, packaging and shipping typically includes: defining Deployments/StatefulSets, Services, Ingress/Gateway routes, ConfigMaps/Secrets references, resource requests/limits, probes, autoscaling, and policies (security context, network policies). It also includes a delivery mechanism such as Helm charts, Kustomize overlays, or GitOps workflows that apply manifests from a source-controlled repository.

Choosing the Right Workload Primitive

Deployment: stateless, horizontally scalable workloads

A Deployment manages a ReplicaSet and is the default choice for stateless services (web APIs, workers that can be replicated). It supports rolling updates, rollback, and declarative scaling. Most application shipping starts with a Deployment plus a Service.

StatefulSet: stable identity and storage

A StatefulSet is used when each replica needs a stable network identity and/or persistent volume claims per replica (databases, queues, some clustered systems). Shipping a StatefulSet usually includes a StorageClass assumption, volume claim templates, and careful update strategy decisions.

Job and CronJob: run-to-completion workloads

Job is for batch tasks that run until completion. CronJob schedules Jobs. Packaging these often includes concurrency policy, backoff limits, deadlines, and resource sizing, plus a clear strategy for passing parameters and handling output.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

DaemonSet: one pod per node

DaemonSet runs a pod on each node (or a subset via node selectors). It’s common for node-level agents (log collectors, monitoring agents). For application developers, DaemonSets appear when you ship supporting components or sidecars as separate node-level services.

From Image to Workload: The Core Kubernetes Objects

A shippable Kubernetes workload is usually a small set of objects that work together. The minimum for a web service is typically: Deployment + Service. Many real workloads add Ingress/Gateway, HPA, PodDisruptionBudget, and NetworkPolicy.

Deployment manifest (baseline)

The Deployment is where you encode runtime configuration: container image, ports, environment variables, probes, resources, security context, and rollout strategy. Keep it environment-agnostic by using placeholders/values injected by Helm or Kustomize rather than hardcoding cluster-specific details.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: orders

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: orders

spec:

replicas: 3

revisionHistoryLimit: 5

strategy:

type: RollingUpdate

rollingUpdate:

maxSurge: 25%

maxUnavailable: 25%

selector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: orders

template:

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: orders

spec:

securityContext:

runAsNonRoot: true

containers:

- name: orders

image: ghcr.io/acme/orders:1.7.2

imagePullPolicy: IfNotPresent

ports:

- name: http

containerPort: 8080

env:

- name: PORT

value: "8080"

resources:

requests:

cpu: "200m"

memory: "256Mi"

limits:

cpu: "1"

memory: "512Mi"

readinessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /ready

port: http

initialDelaySeconds: 5

periodSeconds: 10

livenessProbe:

httpGet:

path: /health

port: http

initialDelaySeconds: 15

periodSeconds: 20Key packaging decisions here include: the label schema (prefer app.kubernetes.io/*), resource sizing, and probe endpoints. These are not “nice to have”: they directly affect scheduling, rollout safety, and autoscaling behavior.

Service manifest (stable networking)

A Service provides stable DNS and load balancing across pods. Even if you use an Ingress/Gateway, you typically still create a ClusterIP Service as the backend target.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: orders

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: orders

spec:

type: ClusterIP

selector:

app.kubernetes.io/name: orders

ports:

- name: http

port: 80

targetPort: httpIngress (or Gateway API) for HTTP exposure

To expose HTTP routes outside the cluster, you can package an Ingress resource (if your cluster uses an Ingress controller) or Gateway API resources (if supported). The exact annotations and class names are environment-specific, so they are good candidates for templating.

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: orders

spec:

ingressClassName: nginx

rules:

- host: orders.example.com

http:

paths:

- path: /

pathType: Prefix

backend:

service:

name: orders

port:

number: 80Configuration and Secrets: Packaging Without Hardcoding

Shipping manifests should avoid embedding environment-specific values (database endpoints, API keys, feature flags). Instead, package your workload to reference configuration sources that can differ per environment.

ConfigMaps for non-sensitive configuration

Use ConfigMaps for values that are safe to store in Git and safe to expose to cluster readers. Prefer explicit keys and stable naming. Mount as environment variables or files.

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: orders-config

data:

LOG_LEVEL: "info"

FEATURE_X_ENABLED: "false"envFrom:

- configMapRef:

name: orders-configSecrets for sensitive configuration

For sensitive values, reference Secrets. In many teams, the Secret object itself is not stored in plain text in Git; instead, it is generated by a secret manager integration or stored encrypted. Regardless of how it is created, your workload packaging should reference it consistently.

env:

- name: DATABASE_URL

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: orders-secrets

key: DATABASE_URLPackaging tip: keep the Secret key names stable across environments so that the Deployment template does not change; only the Secret content changes.

Operational Packaging: Probes, Resources, and Disruptions

Readiness and liveness probes

Readiness gates traffic; liveness triggers restarts. When shipping workloads, define both and ensure the endpoints are lightweight and reliable. A common pattern is: /ready checks dependencies required to serve traffic, while /health checks the process is alive.

Resource requests/limits

Requests drive scheduling and autoscaling signals; limits prevent noisy-neighbor issues. When packaging, start with conservative requests based on profiling or staging measurements. Avoid setting CPU limits too low for latency-sensitive services, as CPU throttling can cause unpredictable response times.

PodDisruptionBudget (PDB)

A PDB helps maintain availability during voluntary disruptions (node drains, upgrades). It’s a shipping artifact that encodes your availability expectations.

apiVersion: policy/v1

kind: PodDisruptionBudget

metadata:

name: orders

spec:

minAvailable: 2

selector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: ordersAutoscaling (HPA)

HorizontalPodAutoscaler is often part of a production-ready package. Even if you don’t enable it in all environments, shipping it as an optional component makes scaling behavior consistent.

apiVersion: autoscaling/v2

kind: HorizontalPodAutoscaler

metadata:

name: orders

spec:

scaleTargetRef:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

name: orders

minReplicas: 2

maxReplicas: 10

metrics:

- type: Resource

resource:

name: cpu

target:

type: Utilization

averageUtilization: 70Step-by-Step: Shipping a Workload with Plain Manifests

This approach is useful for learning and for small internal services. The trade-off is that you must manage environment differences manually or with separate directories.

Step 1: Create a minimal manifest set

- Create

deployment.yamlandservice.yamlas shown above. - If needed, add

ingress.yaml,configmap.yaml, andhpa.yaml.

Step 2: Apply to a namespace

Use a dedicated namespace per app or per team to isolate resources.

kubectl create namespace apps

kubectl -n apps apply -f deployment.yaml

kubectl -n apps apply -f service.yaml

kubectl -n apps apply -f ingress.yamlStep 3: Verify rollout and connectivity

kubectl -n apps rollout status deploy/orders

kubectl -n apps get pods -l app.kubernetes.io/name=orders

kubectl -n apps get svc orders

kubectl -n apps describe ingress ordersStep 4: Update the image (shipping a new version)

When you ship a new image tag, update the Deployment and apply again. Kubernetes will perform a rolling update according to your strategy.

kubectl -n apps set image deploy/orders orders=ghcr.io/acme/orders:1.7.3

kubectl -n apps rollout status deploy/ordersFor repeatability, prefer updating the YAML and applying it, rather than imperative commands, once you move beyond experimentation.

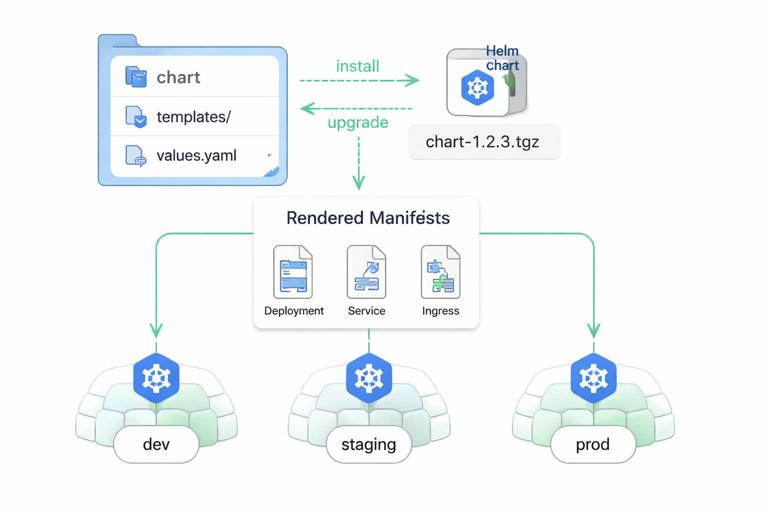

Step-by-Step: Packaging as a Helm Chart

Helm is a packaging format for Kubernetes that lets you template manifests and ship them as a versioned chart. This is especially useful when you need the same workload deployed to multiple environments with different values (replicas, hostnames, resource sizes, feature flags).

Step 1: Create a chart skeleton

helm create ordersThis generates a chart directory with templates and a values.yaml. You will typically remove the example templates and replace them with your own.

Step 2: Define values (the configuration surface)

Design values.yaml to expose only what operators need to change. Keep it small and stable; too many knobs make upgrades risky.

# values.yaml

image:

repository: ghcr.io/acme/orders

tag: "1.7.2"

replicaCount: 3

service:

port: 80

containerPort: 8080

ingress:

enabled: true

className: nginx

host: orders.example.com

resources:

requests:

cpu: 200m

memory: 256Mi

limits:

cpu: "1"

memory: 512MiStep 3: Template the Deployment

In templates/deployment.yaml, replace hardcoded values with Helm expressions. Keep labels consistent across templates.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: {{ include "orders.fullname" . }}

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: {{ include "orders.name" . }}

spec:

replicas: {{ .Values.replicaCount }}

selector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: {{ include "orders.name" . }}

template:

metadata:

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: {{ include "orders.name" . }}

spec:

containers:

- name: orders

image: "{{ .Values.image.repository }}:{{ .Values.image.tag }}"

ports:

- name: http

containerPort: {{ .Values.containerPort }}

resources:

{{ toYaml .Values.resources | indent 10 }}Step 4: Template optional components

For Ingress, wrap the template in a conditional so it can be enabled per environment.

{{- if .Values.ingress.enabled }}

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: {{ include "orders.fullname" . }}

spec:

ingressClassName: {{ .Values.ingress.className }}

rules:

- host: {{ .Values.ingress.host }}

http:

paths:

- path: /

pathType: Prefix

backend:

service:

name: {{ include "orders.fullname" . }}

port:

number: {{ .Values.service.port }}

{{- end }}Step 5: Install and upgrade

helm install orders ./orders -n apps --create-namespace

helm upgrade orders ./orders -n apps --set image.tag=1.7.3Packaging tip: treat the chart as an API. Changing value names or semantics is a breaking change; bump chart versions accordingly and document migrations.

Step-by-Step: Environment Variants with Kustomize

Kustomize is a manifest customization tool built into kubectl. It works well when you want to keep base manifests and apply overlays per environment (dev/staging/prod) without templating logic.

Step 1: Create a base

base/deployment.yaml,base/service.yaml, optionalbase/ingress.yamlbase/kustomization.yamlreferencing those resources

# base/kustomization.yaml

resources:

- deployment.yaml

- service.yamlStep 2: Create overlays

Overlays patch the base. For example, production might increase replicas and set a different image tag.

# overlays/prod/kustomization.yaml

resources:

- ../../base

patches:

- target:

kind: Deployment

name: orders

patch: |-

- op: replace

path: /spec/replicas

value: 6

images:

- name: ghcr.io/acme/orders

newTag: 1.7.3Step 3: Apply an overlay

kubectl apply -k overlays/prod -n appsKustomize packaging tip: keep overlays small and focused. If overlays become complex, consider Helm or a higher-level GitOps pattern that manages per-environment values cleanly.

Versioning and Release Artifacts

Shipping is easier when you define what constitutes a “release.” In Kubernetes, a release commonly includes:

- An immutable container image tag (or digest) that identifies the runtime bits.

- A manifest package version (Helm chart version or Git commit SHA) that identifies the desired state.

- A change log of configuration changes that affect runtime behavior (replicas, resources, flags).

A practical approach is to pin images by digest in production to guarantee immutability, while still using tags for human readability in lower environments. If you use Helm, you can store the chart version separately from the app version and bump them independently when only packaging changes.

Shipping Safety: Rollouts, Rollbacks, and Compatibility

Rollout strategy choices

Rolling updates are the default, but you must ensure your app supports running old and new versions simultaneously during the rollout window. Packaging should reflect this reality: readiness probes must only pass when the instance can serve traffic, and you should avoid schema-breaking changes without a migration strategy.

Rollback mechanics

Kubernetes Deployments keep a rollout history (controlled by revisionHistoryLimit). Helm also tracks release revisions. Packaging should make rollback safe by keeping configuration compatible across versions and by avoiding irreversible changes in the same release as the application update.

Health gates and progressive delivery hooks

Even without advanced tooling, you can ship safer by ensuring that readiness probes reflect real readiness and by setting maxUnavailable to a value that preserves capacity. If you later adopt progressive delivery (canary/blue-green), you will reuse the same packaging primitives (labels, Services, and stable selectors), so it pays to keep them clean and consistent now.

Common Packaging Pitfalls (and How to Avoid Them)

Hardcoding environment details

Hardcoding hostnames, storage classes, node selectors, or secret values makes manifests non-portable. Instead, expose them as Helm values or Kustomize patches, and keep the base workload generic.

Unstable labels and selectors

Changing spec.selector on a Deployment is not allowed and often forces recreation. Choose a stable label key (for example, app.kubernetes.io/name) and never change it after first release.

Missing resource requests

Without requests, the scheduler cannot make good placement decisions, and autoscaling signals become noisy. Always ship requests; treat limits as a deliberate choice rather than a default.

Probes that cause self-inflicted outages

Overly aggressive liveness probes can restart healthy pods during temporary latency spikes. Start with conservative timings, and ensure the liveness endpoint does not depend on external systems.

Shipping “everything” in one chart without boundaries

It’s tempting to package your app plus databases plus ingress controller plus monitoring in one unit. Prefer packaging your application workload separately from shared platform components. Your chart or manifests should focus on what your team owns and can safely upgrade.