Why “Logic” Matters More Than a Long Activity List

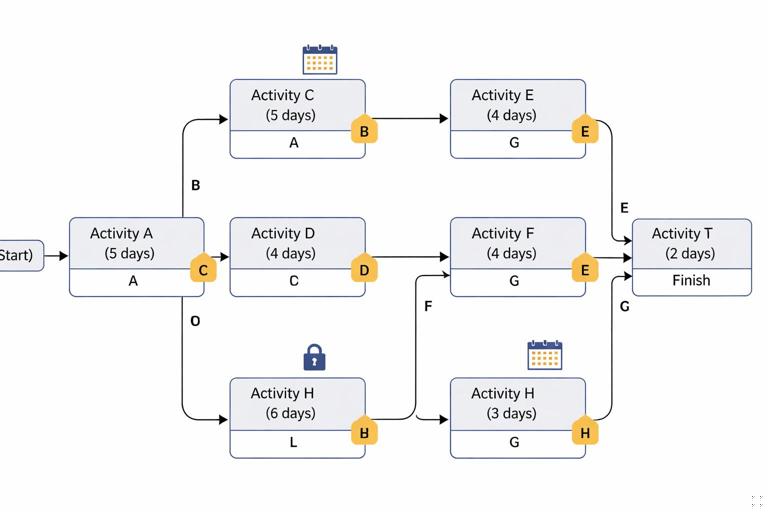

A schedule becomes useful when it behaves like the project will behave. That behavior is created by logic: the cause-and-effect relationships between activities. Logic answers questions like: What must happen before this can start? What can overlap safely? What must finish before inspection? What is allowed to start but cannot finish until something else is done?

In CPM scheduling, logic is built primarily with predecessors and successors (relationships) and refined with constraints (rules that limit dates). Good logic produces a network that responds correctly when you update progress or when a delay hits. Poor logic produces a schedule that looks detailed but gives misleading float, wrong critical path, and unrealistic dates.

Core Terms: Predecessors, Successors, and Relationship Types

An activity is a piece of work with a duration. A predecessor is an activity that must occur before (or in relation to) another activity. A successor is the activity that follows (or is linked after) another activity. The link between them is a relationship.

Finish-to-Start (FS)

FS means the successor cannot start until the predecessor finishes. This is the most common relationship and the easiest to understand.

- Example: “Pour slab” (predecessor) FS → “Start framing” (successor). Framing starts after the slab pour is complete (and typically after cure time, which may be modeled separately).

Start-to-Start (SS)

SS means the successor cannot start until the predecessor starts. This is used for controlled overlap.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

- Example: “Rough-in plumbing” SS → “Rough-in electrical.” Both can start once framing starts, or once the first rooms are ready, depending on how you model it.

Finish-to-Finish (FF)

FF means the successor cannot finish until the predecessor finishes. This is useful when two activities can proceed in parallel but must complete together or in a defined order of completion.

- Example: “Punchlist work” FF → “Final cleaning.” Cleaning can begin while punchlist is underway, but final cleaning cannot finish until punchlist is complete.

Start-to-Finish (SF)

SF means the successor cannot finish until the predecessor starts. This is rare in construction but can model handoffs (e.g., a temporary operation that ends only when a new operation begins).

- Example: “Temporary generator power” SF → “Permanent power online.” The temporary power activity cannot finish until permanent power starts (or is energized, depending on how you define the activities).

Leads and Lags: Modeling Time Offsets Without Breaking Logic

A lag adds time between linked activities; a lead (negative lag) overlaps them. Used carefully, they can model real-world waiting periods and controlled overlap. Used carelessly, they hide logic and make updates difficult.

Lag (positive offset)

- Example: “Concrete pour” FS+3d → “Strip forms.” The stripping starts three days after the pour finishes.

- Example: “Drywall hang” FS+1d → “Tape and mud.” If the crew always returns the next day, a short lag may be appropriate.

Lead (negative offset)

- Example: “Install duct mains” FS-2d → “Start insulation.” Insulation starts two days before duct mains finish (overlap). This can be realistic but can also create confusion if the overlap is not consistently achievable.

Preferred practice: model waiting and overlap explicitly when it matters

Instead of relying on large lags, consider creating explicit activities such as “Concrete cure” or “Inspection wait” when the time is significant, variable, or contractually important. Explicit activities are easier to status, easier to explain, and easier to analyze.

- Better than FS+14d: “Pour slab” FS → “Cure slab (14d)” FS → “Start framing.”

Step-by-Step: Building Logic from a Real Sequence of Work

The goal is to create a network that reflects how crews and approvals actually drive start and finish dates. Use this step-by-step method to build logic consistently.

Step 1: Identify “gates” and “handoffs”

Gates are points where work cannot proceed without a condition being met (inspection, permit, energization, turnover of an area). Handoffs are moments where one trade releases work to another.

- Examples of gates: “Underground inspection passed,” “Structural steel released,” “Permanent power available,” “Fire alarm acceptance test.”

- Examples of handoffs: “Framing complete in Area A,” “Drywall ready for paint,” “Ceiling grid complete for above-ceiling inspection.”

Step 2: Choose the relationship type that matches the physical dependency

Ask: Does the successor need the predecessor to finish, or just to start? Does it need to finish after something else finishes? Use FS by default, and use SS/FF only when overlap is real and repeatable.

- If the successor needs the predecessor’s output (a completed surface, installed equipment, signed-off inspection), use FS.

- If the successor can begin once the predecessor begins producing workable areas, use SS (often with a lag).

- If the successor can proceed but must not complete until the predecessor completes, use FF.

Step 3: Add lags only after you confirm the reason

Before adding a lag, name the reason in your notes or in the activity description (e.g., “cure,” “dry time,” “delivery window,” “inspection notice period”). If you cannot explain the lag in one sentence, it is usually a sign you should model the reason as an activity.

Step 4: Ensure every activity (except project start/end milestones) has at least one predecessor and one successor

Open ends create false float and allow activities to drift without affecting the completion date. A robust CPM network typically has:

- One start milestone with no predecessors.

- One finish milestone with no successors.

- All other activities tied into the network with logical predecessors and successors.

Step 5: Run a “reality check” by walking the job

Mentally simulate the work: if Activity B starts, what must be true on site? If Activity A finishes, what becomes possible next? This walk-through catches missing inspections, temporary works, access limitations, and trade stacking issues.

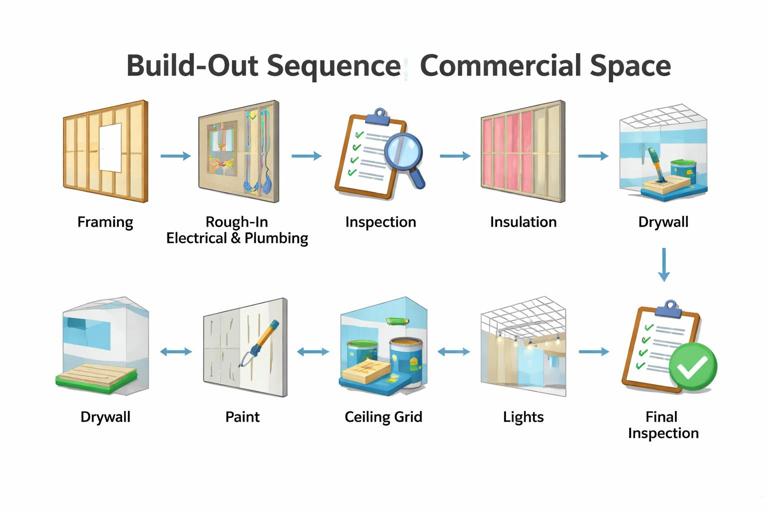

Practical Example: Building Logic for a Small Interior Build-Out

Assume you have these activities (durations omitted for brevity):

- A: Mobilize

- B: Layout

- C: Frame walls

- D: Rough-in electrical

- E: Rough-in plumbing

- F: Above-ceiling inspection

- G: Insulate

- H: Hang drywall

- I: Tape and mud

- J: Prime and paint

- K: Install ceiling grid and tile

- L: Install lights and devices

- M: Final inspection

Step-by-step logic build

Start with the obvious FS chain for gates and handoffs:

- A FS → B (layout after mobilization)

- B FS → C (framing after layout)

Now decide overlap for rough-ins. Rough-ins can often start once framing starts in the first rooms, not necessarily after all framing finishes. That suggests SS relationships with a small lag (or none) depending on your field plan.

- C SS+2d → D (electrical starts two days after framing starts)

- C SS+2d → E (plumbing starts two days after framing starts)

Inspection is a gate: it cannot occur until rough-ins are complete (and often framing is complete in the inspected area). Use FS from both rough-ins (and possibly framing) to inspection.

- D FS → F

- E FS → F

- C FS → F (if the inspector requires framing complete in the inspected area)

Insulation typically follows inspection approval:

- F FS → G

- G FS → H

Taping follows hanging. If your team always returns next day, you might use a short lag; otherwise keep it FS with no lag and let the calendar/crew availability drive it.

- H FS → I

- I FS → J

Ceiling grid often requires painting above-ceiling areas first, and above-ceiling inspection may be required before closing. Depending on your sequence, ceiling grid could follow paint (FS) or overlap (SS). A conservative, easy-to-explain logic is:

- J FS → K

Lights and devices usually follow ceiling and paint completion, and may also require rough-in completion earlier (but that is already embedded). Use FS from ceiling and paint:

- K FS → L

- J FS → L

Final inspection follows completion of devices and finishes:

- L FS → M

This network will respond predictably: if rough-in slips, inspection slips, and downstream work shifts. If framing starts late, rough-ins start late due to SS ties. If paint is delayed, ceiling and devices move accordingly.

Constraints: What They Are and When to Use Them

A constraint is a rule that restricts an activity’s start or finish date regardless of logic. Constraints can be necessary (contractual milestones, access windows, owner-driven dates), but they can also damage the schedule by overriding the network and hiding the true critical path.

Common constraint types (software names vary)

- Start On: activity must start on a specific date.

- Finish On: activity must finish on a specific date.

- Start No Earlier Than (SNET): activity cannot start before a date, but may start later.

- Finish No Later Than (FNLT): activity must finish by a date.

- Mandatory Start / Mandatory Finish: hard constraints that force dates and can break float calculations (use with extreme caution).

Best-practice hierarchy: logic first, constraints last

Use relationships to model cause-and-effect. Use constraints only to represent external rules that logic cannot represent, such as:

- Owner access window: “Tenant move-out complete” or “Weekend shutdown only.”

- Permit effective date: work cannot start before permit issuance.

- Contract milestone: “Substantial completion by June 30.”

- Long-lead delivery date that is fixed by vendor confirmation.

If you find yourself adding constraints to “make the dates look right,” it usually means the logic is missing a predecessor, a gate, a duration, or a calendar.

Step-by-Step: Applying Constraints Without Hiding the Critical Path

Step 1: Confirm the constraint is truly external

Ask: Is this date driven by the project team’s sequence (then it should be logic), or by an outside party/date commitment (then it may be a constraint)?

Step 2: Prefer “No Earlier Than” over “On”

If an activity simply cannot start before a date (e.g., permit not issued), use SNET. This preserves the network’s ability to move later if upstream work slips, without forcing an artificial exact start.

- Example: “Start demolition” SNET = Feb 1 (building access begins Feb 1).

Step 3: Put contractual completion targets on milestones, not on many activities

Instead of constraining multiple finish activities, create a milestone such as “Substantial Completion” and constrain that milestone if required. Then tie all completion-related activities to it with logic. This keeps the network readable and prevents conflicting constraints.

Step 4: Check for negative float and understand why it appears

When a constraint forces a milestone earlier than the logic-driven finish, the schedule may show negative float. Negative float is not “bad data” by itself; it is a signal that the plan, durations, resources, or sequence must change to meet the constrained date.

Logic Quality Checks: How to Spot and Fix Common Problems

Problem 1: Overuse of Finish-to-Start creates unrealistic stacking

If everything is FS, the schedule may prohibit reasonable overlap and show an overly long duration. Fix by introducing SS/FF where overlap is truly workable and repeatable.

- Example fix: Instead of “Frame complete” FS → “Rough-in start,” use “Frame start” SS+lag → “Rough-in start” if crews can follow behind.

Problem 2: Overuse of Start-to-Start creates unrealistic concurrency

If too many activities are SS with zero lag, the schedule may imply that every trade starts on the same day, which is rarely feasible. Add lags or break work into areas/phases so the overlap reflects actual access and production.

Problem 3: Dangling activities (missing predecessors or successors)

Activities without predecessors can start at time zero; activities without successors do not affect completion. Both distort float and critical path. Fix by tying them to the correct gate or handoff.

- Example: “Order doors” has no successor. Add a successor link to “Install doors” (or to “Doors delivered” milestone) so procurement affects installation.

Problem 4: Circular logic

A circular relationship occurs when Activity A depends on B, and B depends on A (directly or through a chain). Scheduling tools will flag this because it is impossible. Fix by clarifying the real dependency and removing the incorrect link.

Problem 5: Hidden logic inside long lags

A 30-day lag might actually include submittals, fabrication, shipping, and receiving. If you need to manage or report those steps, replace the lag with explicit activities and milestones.

Constraints vs. Logic: Choosing the Right Tool in Common Construction Scenarios

Scenario: Permit issuance date is known

Use a milestone “Permit Issued” and tie work to it with FS. If the permit date is fixed externally, you may constrain the milestone with SNET or Start On.

- “Permit Issued” (milestone) Start On = Mar 10

- “Start sitework” FS → from “Permit Issued”

Scenario: Inspection requires 48-hour notice

Model notice as an activity or a lag, depending on how you manage it.

- Option A (explicit): “Request inspection (48h notice)” FS → “Inspection”

- Option B (lag): “Rough-in complete” FS+2d → “Inspection”

If you want accountability for who requests and when, use Option A.

Scenario: Owner only allows shutdown on weekends

Instead of forcing a hard date, consider using a calendar for the shutdown activity (weekends only) and tie it logically. If a specific weekend is mandated, then use a Start On constraint for that shutdown milestone/activity.

Scenario: Material delivery is confirmed for a date

Create a “Material Delivered” milestone constrained to the confirmed delivery date, then link installation FS from that milestone. This prevents installation from floating earlier than delivery and makes the procurement driver visible.

Documenting Logic: Making the Schedule Explainable

Logic that cannot be explained will not be trusted. Use simple documentation habits:

- Use activity names that imply output: “Area A framing complete,” “MEP rough-in complete,” “Inspection passed.”

- For any SS/FF relationship, add a note describing the overlap assumption (e.g., “Electrical follows framing by 2 days per floor”).

- For any constraint, record the source (contract clause, owner email, permit letter, vendor confirmation).

Mini Workshop: Convert Field Notes into CPM Logic

Take this field note: “We can start duct rough-in once the first corridor is framed. Electrical can start shortly after. Above-ceiling inspection happens per zone; insulation and drywall follow. Ceiling grid can start after prime. Devices after ceiling. Final inspection after devices.”

Convert it into logic in a repeatable way:

- Create zone-based activities (Zone 1, Zone 2, etc.) if the project is large enough to benefit from phased turnover.

- Use SS with lag for “follow-behind” trades: framing start SS+lag → duct start; framing start SS+lag → electrical start.

- Use FS for gates: rough-ins FS → inspection; inspection FS → insulation; insulation FS → drywall.

- Use FS for finish handoffs: prime FS → ceiling grid; ceiling grid FS → devices; devices FS → final inspection.

This approach turns narrative sequencing into a network that can be updated weekly and will show the true drivers when something changes.