Why internal negotiations are different (and why they matter)

Internal negotiations are the agreements you make inside your organization to secure priorities, resources, and scope: headcount, budget, timelines, access to data, engineering capacity, legal review time, marketing support, or the right to say “no” to extra work. Unlike external deals, you rarely have the option to walk away cleanly. You will likely work with the same people next week, and the “currency” is not only money—it includes attention, risk, reputation, and future reciprocity.

Internal negotiations also happen under constraints that are easy to underestimate: shared leadership goals, fixed planning cycles, cross-team dependencies, and invisible workload. People can agree verbally but still fail to deliver because their own priorities shift or because they never truly had the capacity. That is why internal negotiation is not just persuasion; it is operational agreement-making: clarifying what will be done, by whom, by when, with what resources, and what will not be done.

The three levers: priorities, resources, and scope

1) Priorities: deciding what matters now

Priority negotiation is about sequencing and focus. Most internal conflict is not about whether something is valuable; it is about whether it is valuable enough to displace something else. When you ask a team for support, you are implicitly asking them to move your work up their list. The practical question to solve is: “What gets deprioritized or delayed to make room?”

Priority agreements should be explicit. If they are not, you may receive a polite “yes” that translates into “we’ll try,” which often becomes “we didn’t get to it.”

2) Resources: capacity, budget, and access

Resources include tangible items (budget, tools, contractors) and intangible ones (time from senior experts, decision-maker attention, access to customers, data permissions). Internal resource negotiations often fail because requests are framed as “help us” rather than “here is the capacity trade we are proposing.”

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Resource commitments should be measurable: number of hours per week, named individuals, service-level expectations (e.g., review within 48 hours), and escalation paths when capacity is squeezed.

3) Scope: what is included, excluded, and the quality bar

Scope is the boundary of work: features, deliverables, acceptance criteria, and non-goals. Scope negotiation is where you prevent “silent expansion”—the gradual addition of requirements without corresponding time or resources. Internally, scope creep often comes from good intentions (“while you’re at it…”) and from risk management (“we need one more check”).

Scope agreements should include a definition of “done,” a change-control mechanism, and explicit trade-offs (if scope increases, what moves: timeline, resources, or quality).

Common internal negotiation scenarios (and what is really being negotiated)

- Project timelines: negotiating sequencing, dependency ownership, and what can be parallelized.

- Headcount or staffing: negotiating which outcomes justify capacity, and what work stops if staffing is approved.

- Cross-functional support (engineering, design, data, legal, finance): negotiating service levels, prioritization, and risk tolerance.

- Scope changes from leadership: negotiating the “triangle” of scope/time/resources and protecting quality.

- Operational process changes: negotiating who bears the transition cost and how success will be measured.

- Budget reallocation: negotiating opportunity cost, timing, and accountability for results.

A practical step-by-step: the Internal Agreement Canvas

Use the following step-by-step structure to turn a vague request into a concrete internal agreement. This is designed for non-sales roles (product, operations, HR, finance, engineering, analytics, legal, customer success) where execution reliability matters as much as “getting to yes.”

Step 1: State the decision and the deadline

Internal negotiations drift when the decision is unclear. Start with a crisp decision statement and a time constraint.

- Decision: “Approve two weeks of engineering time in February for the onboarding experiment.”

- Deadline: “We need confirmation by Friday to hit the release train.”

If there is no real deadline, say so. Artificial urgency erodes trust and invites pushback later.

Step 2: Define the deliverable and the “definition of done”

Many internal conflicts are scope conflicts disguised as priority conflicts. Prevent that by specifying what success looks like in observable terms.

- Deliverable: “A new onboarding flow for segment A.”

- Definition of done: “Shipped behind a feature flag, tracked with event X, with rollback plan, and QA completed.”

Include quality and risk requirements up front (security review, compliance checks, performance thresholds). If you omit them, they will reappear later as “surprises.”

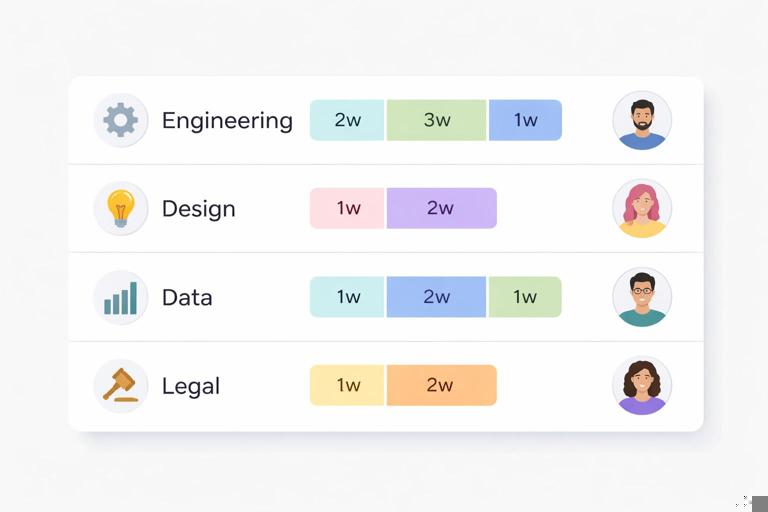

Step 3: List required inputs and name owners

Translate “support” into specific inputs. Name the function, the role, and the expected effort.

- Engineering: “1 backend engineer, 6 days; 1 frontend engineer, 4 days.”

- Design: “1 designer, 2 days for flow + assets.”

- Data: “1 analyst, 1 day for tracking plan + dashboard.”

- Legal: “Review copy and consent language within 3 business days.”

If you cannot name individuals yet, name the team and ask for a single point of contact who can allocate internally.

Step 4: Surface constraints and non-negotiables

Internal partners often have constraints you do not see: on-call rotations, quarter-end close, audit windows, or a major launch. Invite constraints early so you can design around them.

Also state your non-negotiables clearly (e.g., “We cannot ship without security sign-off,” or “We must meet the regulatory deadline”). This prevents later pressure to “just make an exception.”

Step 5: Propose a trade-off package (not a single ask)

Internal negotiation works best when you present options that respect capacity. Instead of “Can you do this?” offer packages that vary scope, timeline, and resource load.

Example packages for an internal tool request:

- Package A (fast, narrow): 2 weeks, minimal UI, covers top 3 workflows, manual backfill.

- Package B (balanced): 4 weeks, includes permissions and audit logs, automated backfill.

- Package C (robust, slower): 6–8 weeks, full workflow coverage, integrations, performance hardening.

Packages make it easier for partners to say “yes” to something without feeling trapped by an all-or-nothing request.

Step 6: Make the opportunity cost explicit

Because internal teams share goals, people often avoid stating what will be delayed. But without opportunity cost, priority is not real.

Use a neutral, operational framing:

- “If we take Package B in February, which of these items moves to March: bug backlog reduction, the reporting migration, or the partner API?”

- “If we keep the current timeline, we will need either additional QA support or a reduced test matrix. Which is acceptable?”

This is not a threat; it is a planning requirement.

Step 7: Agree on decision rights and escalation

Internal negotiations stall when nobody knows who can decide. Clarify:

- Decision maker: who can approve the trade-off (e.g., engineering manager, product director).

- Consulted roles: who must be consulted (security, finance).

- Escalation path: what happens if priorities conflict (e.g., “If we can’t resolve by Thursday, we bring it to the weekly leadership sync”).

Escalation should be framed as a normal mechanism, not a punishment.

Step 8: Write the agreement in a one-page “working contract”

Verbal alignment is fragile. Capture the agreement in a short document or message that includes:

- Goal and success metric

- Scope (in/out)

- Owners and time commitments

- Milestones and dates

- Risks and assumptions

- Change-control rule (how new requests are handled)

Keep it short enough that people will actually read it. The purpose is shared memory and accountability, not bureaucracy.

Negotiating priorities: how to get real commitment (not polite agreement)

Use “priority language” instead of “importance language”

People will agree your work is important. That does not mean it is prioritized. Use language that forces ordering:

- “Where does this sit in your top five for the next two weeks?”

- “What is the item this displaces?”

- “If we can only do one thing this sprint, is it this or the reliability work?”

Ask for a calendar commitment

Priority becomes real when it appears on a plan: sprint board, roadmap, capacity sheet, or calendar. A practical move is to ask for a specific scheduling action:

- “Can we put the design review on Tuesday and reserve two engineering days next week?”

This converts abstract support into an operational commitment.

Use “if-then” agreements to handle uncertainty

Internal work often depends on unknowns (bug volume, incident response). Use conditional commitments:

- “If there are no P0 incidents next week, we will complete the API changes by Thursday; if incidents occur, we will deliver the tracking plan and reschedule implementation.”

This protects relationships because it acknowledges reality while still creating a plan.

Negotiating resources: getting capacity without triggering defensiveness

Translate your request into workload units

“We need help” is hard to evaluate. Convert to workload units that match how the other team plans:

- Engineering: story points, days, or sprint capacity

- Legal: number of documents, complexity level, turnaround time

- Finance: hours of analysis, number of scenarios

- Data: number of events, dashboards, pipelines

Then ask for confirmation: “Is this estimate realistic from your side?” This invites collaboration rather than debate.

Offer resource substitutions

When the exact resource is scarce, propose substitutes:

- “If senior engineer time is limited, could we get 2 hours of architecture review and use a junior engineer for implementation?”

- “If legal cannot review full copy this week, can we get pre-approved templates and a quick spot-check?”

Substitutions reduce the “all or nothing” pressure.

Negotiate access as a resource

Access is often the hidden bottleneck: access to customer calls, production data, decision-makers, or systems. Treat access like any other resource with clear terms:

- “We need two customer interviews with segment A by next Wednesday; can your team recruit and schedule them?”

- “We need read-only access to dataset X for three analysts; approval by Monday.”

Negotiating scope: controlling change without being labeled “difficult”

Use a scope boundary statement

A boundary statement is a short, neutral sentence that defines what is included and excluded. Example:

- “This phase covers onboarding for new users in region 1. It does not include migration of existing users or localization.”

Boundary statements reduce misunderstandings and make later trade-offs easier.

Install a change-control rule that feels fair

Change control does not need to be heavy. A simple rule can be:

- “New requirements are welcome, but we will review them weekly and decide whether to swap them with existing items or move the deadline.”

This frames scope control as a shared decision, not a refusal.

Separate “nice-to-have” from “must-have” with acceptance criteria

Scope arguments often happen because “must-have” is undefined. Use acceptance criteria to make it concrete:

- Must-have: “Users can complete onboarding in under 3 minutes; events are tracked; rollback exists.”

- Nice-to-have: “Animated tips; personalized recommendations; multi-language support.”

When pressure arrives, you can protect the must-haves while flexing the nice-to-haves.

Practical scripts for internal negotiations (adapt and use)

When you need a clear priority decision

“I want to make sure we’re not just aligned in principle. For the next two weeks, is this in your top three? If yes, what moves down to make room?”

When you suspect a “yes” is actually a “maybe”

“I’m hearing support, but I’m not sure we have capacity locked. What would prevent this from happening as planned? Let’s name it now and adjust.”

When leadership adds scope late

“We can include that. To keep the date, we would need to drop X and Y, or add Z days of engineering. Which trade-off do you prefer?”

When another team is overloaded

“Given your current load, what is the smallest version you can commit to reliably? We can design around that and phase the rest.”

When you need faster reviews (legal, security, finance)

“What would make a 48-hour turnaround feasible? If we provide a template, a risk summary, and a single point of contact, can we agree on that service level for this project?”

Mini case studies (realistic examples)

Case 1: Operations negotiating scope with Product

Situation: Operations is asked to “improve onboarding” but receives new requests weekly: new email sequences, training content, CRM changes.

Internal negotiation move: Ops proposes a two-phase scope agreement.

- Phase 1 (2 weeks): update onboarding checklist, add two automated emails, create a single training deck. Definition of done includes adoption metric and support ticket reduction.

- Phase 2 (later): CRM workflow redesign and advanced segmentation.

Resulting agreement: Product agrees to freeze Phase 1 scope and route new requests into a weekly review where each new item must replace an existing one or move to Phase 2.

Case 2: Data team negotiating priorities with Marketing

Situation: Marketing requests “a dashboard” but the data team has a migration deadline.

Internal negotiation move: Data offers packages:

- Quick dashboard: 1 day, uses existing tables, limited segmentation.

- Full dashboard: 1–2 weeks, new pipeline, validated metrics.

Opportunity cost made explicit: “If we do the full dashboard now, the migration slips by one week and increases risk. If we do the quick dashboard, you get directional insight this week.”

Resulting agreement: Marketing chooses the quick version now and schedules the full version after migration, with a named owner and date.

Case 3: Engineering negotiating resources with Security

Situation: Engineering needs security review for a new integration, but security is understaffed.

Internal negotiation move: Engineering proposes a resource substitution: a 60-minute threat-model session plus a checklist-based review, instead of a full audit.

Scope boundary: “We will limit the integration to read-only access in Phase 1; write access is out of scope until the full audit.”

Resulting agreement: Security agrees to the lighter review with clear conditions, and the project ships safely within the timeline.

Tools to keep internal agreements from unraveling

1) The “single source of truth” note

Create one shared note (or ticket) that contains the working contract. Link it in chat and meeting invites. When someone asks for a change, update the note and tag the impacted owners. This prevents parallel versions of reality.

2) Milestone check-ins focused on trade-offs

Status meetings become political when they are only about progress. Make them about trade-offs:

- “What changed in capacity?”

- “What new risks appeared?”

- “Do we need to adjust scope, timeline, or resources?”

This keeps negotiation continuous and reduces last-minute conflict.

3) A lightweight RACI for cross-team work

For complex projects, list who is Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed for each major deliverable. Keep it minimal—only the deliverables that commonly cause confusion (e.g., requirements sign-off, launch approval, comms, incident response).

4) Pre-mortem for internal delivery risk

Before committing, run a 10-minute pre-mortem: “Assume this fails. What caused it?” Capture the top 5 risks and assign mitigations. This is especially useful when negotiating resources because it turns “we’re too busy” into specific risk items you can address.

What to do when internal negotiations get stuck

Diagnose the stuck point: priority, resource, or scope

Stalls often happen because people argue on the surface while the real issue is different. Use a direct diagnostic question:

- “Is the issue that this isn’t a priority, that you don’t have capacity, or that the scope feels risky?”

Each answer leads to a different solution: reprioritization, resourcing changes, or scope/risk reduction.

Use a “decision memo” to force clarity

When debate loops, write a short decision memo with options and trade-offs:

Decision needed: Choose delivery approach for Q2 compliance update by Jan 15. Option 1: Minimal scope, meet deadline, lower automation. Option 2: Full automation, slip by 3 weeks, requires 1 contractor. Risks: audit exposure if deadline missed; operational cost if automation deferred. Recommendation: Option 1 now, Option 2 scheduled for Q3.Send it to the decision maker and ask for a choice by a specific date. This reduces endless discussion and makes the trade-offs visible.

Escalate with neutrality and shared goals

Escalation is appropriate when trade-offs affect multiple teams and cannot be resolved at your level. Keep it neutral:

- “We have two valid priorities competing for the same capacity. We need a leadership decision on which outcome to optimize for this month.”

Bring options, not complaints.