Why “business hypothesis” is not yet a causal question

Teams often start with statements like “Free shipping will increase sales,” “A new onboarding flow will reduce churn,” or “Raising prices won’t hurt demand.” These are useful business hypotheses because they express intent and expected direction. But they are not yet testable causal questions because they usually leave key elements ambiguous: what exactly changes, for whom, when, compared to what baseline, and which outcome window matters for the decision.

A causal question is operational: it specifies an intervention (what you will do), a target population (who is affected), a comparison condition (what would happen otherwise), a time horizon (when effects are measured), and an estimand (the precise quantity you want to estimate). Turning a hypothesis into a causal question is the bridge between strategy and evidence. It is also the difference between “we saw a lift” and “we can confidently choose option A over option B.”

In practice, the transformation is a structured translation exercise. You take a narrative claim and rewrite it into a question that an experiment, quasi-experiment, or causal model can answer unambiguously.

The anatomy of a testable causal question

A well-formed causal question typically includes the following components. You do not always need to write them as a single sentence, but you should be able to point to each element explicitly.

1) The intervention (actionable change)

The intervention must be something you can set or assign, at least in principle. “Customer satisfaction” is not an intervention; “send a proactive support email within 24 hours of first login” is. Interventions should be described at the level of implementation details that matter for replication: what is delivered, through which channel, with what eligibility rules.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

2) The comparison condition (baseline or alternative)

Every causal claim is relative to a counterfactual baseline: what would happen if you did not apply the intervention, or if you applied a different one. The baseline might be “current experience,” “no message,” “existing pricing,” or “variant B.” If the baseline is unclear, the question is not testable because different baselines can imply different effects.

3) The unit and population (who/what is affected)

Specify the unit of analysis (user, account, session, store, region, sales rep) and the population you care about. “New users in the US on mobile who completed signup” is different from “all users.” This matters because effects can vary across segments, and because feasibility and interference issues depend on the unit.

4) The outcome and measurement window (what changes, and when)

Outcomes must be measurable and aligned with the decision. “Engagement” is vague; “number of active days in the first 14 days after signup” is measurable. Also specify the window: immediate (same session), short-term (7 days), medium-term (30–90 days), or long-term (annual retention). Many interventions shift timing rather than total value, so the window can change the sign of the effect.

5) The estimand (the exact effect you want)

Different estimands answer different business decisions. Examples include average treatment effect (ATE) for all eligible units, effect on the treated (when not everyone complies), or conditional effects for a segment. You do not need advanced notation, but you should state whether you want the average effect, the effect among compliers, or the effect for a specific subgroup.

6) The decision threshold (how big is “worth it”)

While not strictly part of the causal estimand, a testable business question benefits from a minimum detectable or minimum worthwhile effect: “We will ship if conversion increases by at least 0.5 percentage points without increasing refunds.” This prevents “statistically significant but irrelevant” wins and clarifies trade-offs.

A practical translation workflow: from hypothesis to causal question

The following step-by-step workflow can be used in planning meetings to convert fuzzy hypotheses into testable causal questions. It is designed to be fast enough for real teams, but rigorous enough to prevent common misinterpretations.

Step 1: Write the hypothesis in plain language

Capture the business belief as the team currently states it. Do not correct it yet.

- Example: “Adding live chat will reduce churn.”

Step 2: Identify the decision that depends on the answer

Ask: what will we do differently depending on the result? This forces clarity on scope and constraints.

- Decision: “Should we invest in staffing live chat 24/7 for all customers, only for high-value customers, or not at all?”

Step 3: Specify the intervention precisely

Define what “adding live chat” means operationally. Include eligibility and delivery rules.

- Intervention: “Show an in-app live chat widget on the billing page and dashboard; route chats to agents 9am–9pm local time; eligible accounts are paid plans with at least 3 active seats.”

Step 4: Define the baseline or alternative

Clarify what happens without the change. If there are multiple plausible baselines, pick the one that matches the decision.

- Baseline: “No live chat widget; support remains email-only with current SLA.”

Step 5: Choose unit, population, and timing

Pick the unit that the intervention is assigned to and the population you want to generalize to. Specify when outcomes are measured relative to assignment.

- Unit: account

- Population: eligible paid accounts in North America

- Timing: measure churn within 60 days after first exposure to the widget

Step 6: Define primary outcome and guardrails

Choose one primary outcome for decision-making, plus guardrails to detect harm or gaming.

- Primary outcome: 60-day account churn rate

- Guardrails: support cost per account, refund rate, CSAT, time-to-resolution

Step 7: State the estimand in business terms

Write the effect as a difference between intervention and baseline for the chosen population and window.

- Estimand: “Average change in 60-day churn rate for eligible paid accounts if we enable the live chat widget versus keep email-only support.”

Step 8: Add a minimum worthwhile effect and constraints

Define what magnitude justifies rollout given costs and operational limits.

- Threshold: “At least a 1.0 percentage point reduction in 60-day churn, while keeping support cost increase under $2 per account per month.”

Step 9: Check for ambiguity and hidden multiple questions

Many hypotheses bundle several mechanisms. Split them into separate questions if needed.

- Bundled: “Live chat reduces churn because customers get faster help.”

- Split: (a) effect on churn, (b) effect on time-to-resolution, (c) mediation question about whether time-to-resolution explains churn changes.

Common patterns of business hypotheses and how to rewrite them

Pattern A: “Feature X will increase metric Y”

These hypotheses often omit the baseline, the population, and the window.

- Hypothesis: “Personalized recommendations will increase revenue.”

- Testable causal question: “For returning users who have made at least one purchase in the last 90 days, what is the average change in revenue per user over the next 30 days if we show a personalized recommendation carousel on the home page versus showing the generic bestseller carousel?”

Pattern B: “Campaign X drives growth”

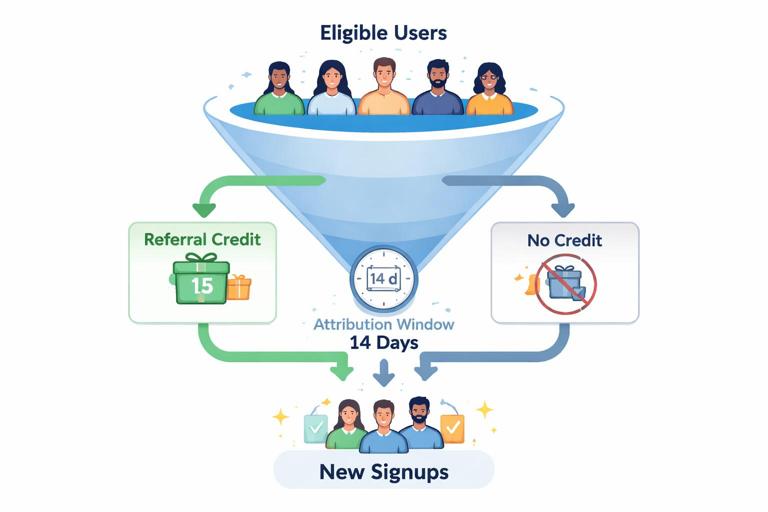

Campaigns often have spillovers and timing effects. The question should specify attribution window and unit.

- Hypothesis: “A referral bonus will drive new signups.”

- Testable causal question: “Among existing active users eligible for referrals, what is the average change in the number of referred signups within 14 days if we offer a $10 referral credit versus no referral credit?”

Pattern C: “Price change won’t hurt demand”

Pricing hypotheses must define the price schedule and the demand metric, and often require segment-specific estimands.

- Hypothesis: “We can raise prices without losing customers.”

- Testable causal question: “For new subscriptions started in the US, what is the average change in conversion rate and first-30-day revenue if we increase the monthly price from $29 to $35 versus keeping it at $29, measured at checkout over a 21-day test period?”

Pattern D: “Operational improvement will reduce costs”

Cost-saving interventions can shift costs elsewhere; guardrails are essential.

- Hypothesis: “Automating ticket triage will reduce support costs.”

- Testable causal question: “For incoming support tickets, what is the average change in cost per resolved ticket and resolution time if we use automated triage to route tickets versus manual routing, measured over 4 weeks, while maintaining CSAT above 4.2/5?”

Turning “why” questions into testable causal questions

Stakeholders often ask “Why did churn increase?” or “Why are conversions down?” These are diagnostic questions, not directly intervention questions. To make them causal and testable, reframe them as “Which change, if applied, would move the outcome?” or “Which candidate drivers, if altered, would change the outcome?”

A practical approach is to list plausible levers and convert each into a separate causal question. This avoids the trap of trying to infer causality from a single observed change in a complex system.

- Diagnostic prompt: “Why did churn increase last month?”

- Candidate levers: billing email timing, onboarding completion, product outages, price changes, support backlog

- Converted causal questions: “What is the effect of sending the billing reminder 7 days before renewal versus 2 days before renewal on renewal rate?” and “What is the effect of reducing onboarding steps from 6 to 4 on 14-day activation and 60-day churn?”

Scope control: avoid the “everything changed” causal question

Business initiatives are often bundles: “We redesigned the homepage, changed navigation, updated copy, and launched a new promo.” A single causal question about the whole bundle may be testable, but it is often not decision-useful because you cannot learn which component mattered, and you cannot iterate efficiently.

Use scope control techniques:

Define the minimal intervention: isolate one change that is feasible to test independently.

Use factorial thinking: if you must change multiple components, plan questions that separate main effects (e.g., copy vs layout) rather than only the combined effect.

Prioritize by reversibility: test changes that are easy to roll back first, so you can learn quickly with lower risk.

Choosing the right time horizon: short-term lifts vs durable effects

Many business hypotheses implicitly assume that short-term improvements translate into long-term value. For example, a more aggressive discount might boost same-day conversion but reduce long-term margin or attract low-retention customers. A testable causal question should explicitly state the horizon and, when needed, include both near-term and longer-term outcomes.

Practical guidance:

If the intervention affects first-time conversion, include at least one downstream outcome such as 30-day retention, refund rate, or repeat purchase rate.

If the intervention affects engagement, include a business outcome that engagement is supposed to drive (e.g., upgrades, renewals), not only clicks.

When long-term outcomes are slow, define a leading indicator that is validated as predictive, and write the question as a two-stage decision: “Ship if leading indicator improves and guardrails hold; then run a longer follow-up.”

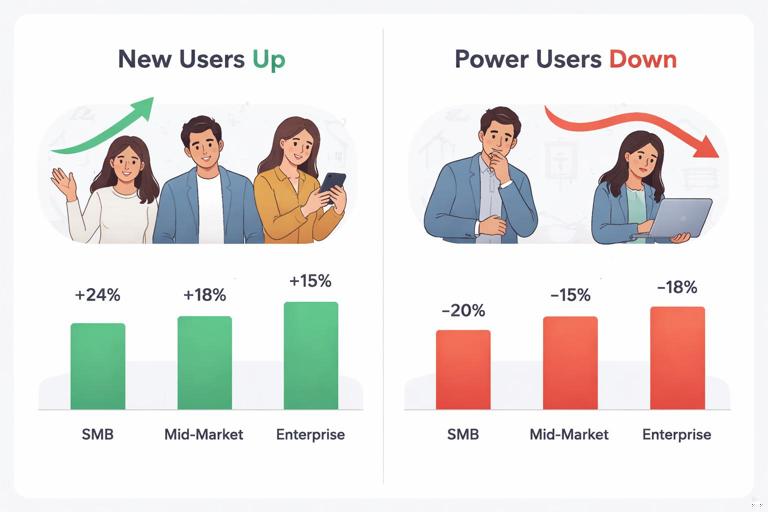

Handling heterogeneity: when one average effect is not enough

Business decisions often depend on segment-specific effects: a change might help new users but hurt power users, or increase revenue for enterprise accounts but reduce satisfaction for small businesses. A testable causal question can incorporate heterogeneity in two ways: by defining the population narrowly, or by explicitly asking for conditional effects.

Narrow population approach: “For new users who have not completed onboarding within 24 hours…”

Conditional effect approach: “What is the effect on churn for SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise accounts?”

Be careful not to turn every hypothesis into dozens of subgroup questions. A practical rule is to pre-specify a small number of segments that correspond to real operational decisions (e.g., different rollout rules, different pricing tiers, different eligibility criteria).

Interference and network effects: when one unit’s treatment affects another

Some hypotheses involve spillovers: “If we improve driver incentives, delivery times will improve,” “If we change marketplace ranking, sellers will adjust prices,” “If we add a social sharing feature, users influence each other.” In these cases, a naive causal question at the individual level can be ill-posed because the effect depends on how many others are treated.

To make the question testable, include the exposure regime:

Individual-level intervention with minimal spillover: “Show feature to a user” may be fine if others are unaffected.

Cluster-level intervention: “Enable feature for all users in a region” when interactions are local.

Saturation-based question: “What is the effect on engagement when 30% of a user’s contacts have access versus 0%?”

Even if you do not yet design the experiment, writing the question this way prevents misinterpretation of results from partial rollouts.

From causal question to a pre-analysis checklist (without repeating prior material)

Once the causal question is written, teams can use a lightweight checklist to ensure it is ready for testing and decision-making. This is not about statistical technique; it is about clarity and operational readiness.

Actionability: Can we actually implement the intervention as specified, and can we keep the baseline stable during the test?

Observability: Can we measure the outcome and guardrails reliably for the chosen unit and window?

Interpretability: If the effect is positive, do we know what decision we will take? If negative, do we know what we will do instead?

Risk controls: Are there safety or brand constraints that require staged rollout or stricter guardrails?

Operational constraints: Are there capacity limits (support staffing, inventory, budget) that mean the effect under full rollout could differ from the effect under test conditions?

Worked examples: rewriting real-world hypotheses

Example 1: E-commerce checkout friction

Business hypothesis: “Reducing checkout steps will increase purchases.”

Clarify the intervention: Remove the “create account” step and allow guest checkout, while keeping payment options unchanged.

Define baseline: Current checkout requires account creation before payment.

Unit and population: Sessions from new visitors on mobile web in the US.

Outcome and window: Purchase conversion within the same session; guardrails include fraud rate and refund rate within 30 days.

Testable causal question: “For mobile web sessions from new US visitors, what is the average change in same-session purchase conversion if we enable guest checkout (no account creation required) versus requiring account creation, while monitoring 30-day fraud and refund rates?”

Example 2: B2B SaaS activation messaging

Business hypothesis: “Sending onboarding emails will improve activation.”

Clarify the intervention: A 3-email sequence triggered after signup: day 0 setup guide, day 2 use-case template, day 5 invitation to a live webinar.

Baseline: No automated onboarding emails; only a welcome email.

Unit and population: New accounts created via self-serve signup; exclude accounts created by sales.

Outcome and window: Activation defined as completing key setup actions within 14 days; guardrails include unsubscribe rate and support ticket volume.

Testable causal question: “Among self-serve new accounts, what is the average change in 14-day activation rate if we send a 3-email onboarding sequence versus sending only the welcome email, while tracking unsubscribe rate and support tickets per account?”

Example 3: Marketplace ranking change

Business hypothesis: “Ranking by fastest delivery will increase conversion.”

Clarify the intervention: Change default sort order on category pages to prioritize listings with estimated delivery under 2 days.

Baseline: Current ranking prioritizes relevance score and price competitiveness.

Unit and population: Category-page visits; note potential seller response and inventory shifts.

Outcome and window: Conversion per visit and gross merchandise value over 7 days; guardrails include seller cancellations and customer complaints.

Testable causal question: “For category-page visits in the electronics category, what is the average change in 7-day conversion per visit and GMV if we rank listings primarily by fastest delivery versus the current relevance/price ranking, while monitoring seller cancellation rate and complaint rate?”

Templates you can reuse in planning documents

Use these fill-in-the-blank templates to standardize how your organization writes causal questions. The goal is consistency and fewer misunderstandings across product, marketing, finance, and data teams.

Template 1: Simple A vs current

“For [population] at the [unit] level, what is the average change in [primary outcome] over [time window] if we [intervention] versus [baseline], while ensuring [guardrails] do not worsen beyond [thresholds]?”

Template 2: Multiple outcomes with trade-offs

“What is the effect of [intervention] versus [baseline] on [outcome 1] and [outcome 2] for [population] over [window], and does it meet the decision rule: [minimum worthwhile effect] with [constraints]?”

Template 3: Segment-aware question

“For [population], what is the effect of [intervention] versus [baseline] on [outcome] over [window], and how does the effect differ across [pre-specified segments] that correspond to [operational decisions]?”

Operationalizing the question into test specifications (practical steps)

After you have the testable causal question, you can translate it into a test specification document that engineering, analytics, and stakeholders can execute. The steps below focus on turning the question into implementable requirements, without relying on any single evaluation method.

Step 1: Define eligibility and exposure rules

Eligibility: who can be assigned (e.g., new users only, paid plans only).

Exposure: what counts as “treated” (e.g., saw the widget at least once, received the email, encountered new price at checkout).

Exclusions: bots, internal users, edge cases (e.g., chargebacks, enterprise contracts).

Step 2: Define event instrumentation and data sources

List required events (e.g., “checkout_started,” “purchase_completed,” “chat_opened,” “ticket_resolved”).

Specify source of truth for outcomes (billing system vs analytics events).

Define how to handle missing data and delayed reporting.

Step 3: Pre-specify outcome calculations

Exact formula for rates and denominators (per user, per session, per account).

Time window alignment (e.g., 14 days from signup timestamp, not calendar weeks).

Handling of multiple exposures (e.g., first exposure date anchors the window).

Step 4: Define guardrails and stop conditions

Guardrail thresholds (e.g., fraud rate must not increase by more than 0.2 percentage points).

Operational stop rules (e.g., if support backlog exceeds capacity, pause rollout).

Ethical or compliance constraints (e.g., pricing transparency requirements).

Step 5: Define the decision rule

Write a simple “if/then” rule that maps results to action. This keeps the organization honest about what evidence is needed.

If primary outcome improves by at least X and guardrails stay within limits, then roll out to Y% of population. If primary outcome is neutral but guardrails improve (e.g., cost decreases), then run follow-up test focused on long-term outcomes. If guardrails worsen beyond limits, do not roll out and investigate failure modes.