What “Breaks in Production” Really Means

Definition and scope: In production, cryptography rarely “breaks” because AES or RSA suddenly fails. It breaks because real systems violate assumptions: keys leak, randomness degrades, time and state drift, libraries are misused, or operational processes create new attack surfaces. A production failure case is any situation where the system still appears to work for legitimate users, but confidentiality, integrity, or authenticity is silently lost.

Why these failures are hard to notice: Crypto failures often look like normal bugs: intermittent login issues, occasional signature verification errors, or “works on my machine” differences between environments. Many failures are partial: only some tenants, some regions, some time windows, or only after a deploy. Attackers exploit exactly these edges because monitoring typically focuses on availability, not on cryptographic correctness.

Failure Case 1: Randomness and Nonce Mismanagement

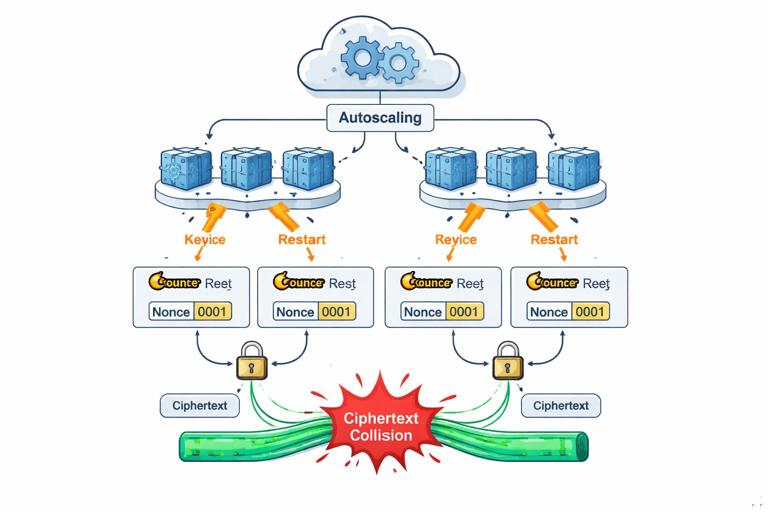

What goes wrong: Many modern schemes require a unique nonce/IV per encryption under a given key. In production, uniqueness can fail due to counter resets, multi-process concurrency, container restarts, VM snapshots, or using time-based nonces with insufficient resolution. Even if the underlying cipher is strong, nonce reuse can catastrophically reveal plaintext relationships or allow forgeries depending on the mode.

Step-by-step: How nonce reuse happens in real deployments

- Step 1 — A developer chooses a “simple” nonce: e.g., nonce = current timestamp in milliseconds, or a per-process counter stored in memory.

- Step 2 — The service scales horizontally: multiple instances start at the same time, producing the same timestamp-derived nonce or the same counter starting value.

- Step 3 — A restart or autoscaling event occurs: counters reset; timestamps collide under load; a snapshot restores a VM with the same counter state.

- Step 4 — Two encryptions under the same key reuse a nonce: the system still decrypts fine, so no one notices.

- Step 5 — An attacker collects ciphertexts: they exploit nonce reuse to infer relationships (e.g., XOR of plaintexts in some constructions) or to forge messages in certain AEAD misuse scenarios.

Practical mitigations you can implement

Use library-managed nonces when possible: Prefer APIs that generate nonces internally and return them with the ciphertext. If you must supply a nonce, generate it using a cryptographically secure RNG and ensure uniqueness by design.

Make nonce uniqueness resilient to restarts: If you use counters, persist them durably and atomically (and handle rollback). If you use random nonces, ensure the RNG is strong and properly seeded in all environments, including early boot and minimal containers.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

// Example pattern: store nonce alongside ciphertext; nonce generated via CSPRNG. Pseudocode. nonce = CSPRNG.randomBytes(12) ciphertext = AEAD_Encrypt(key, nonce, plaintext, aad) store(nonce || ciphertext)Failure Case 2: Key/Algorithm Confusion and “Works with the Wrong Key”

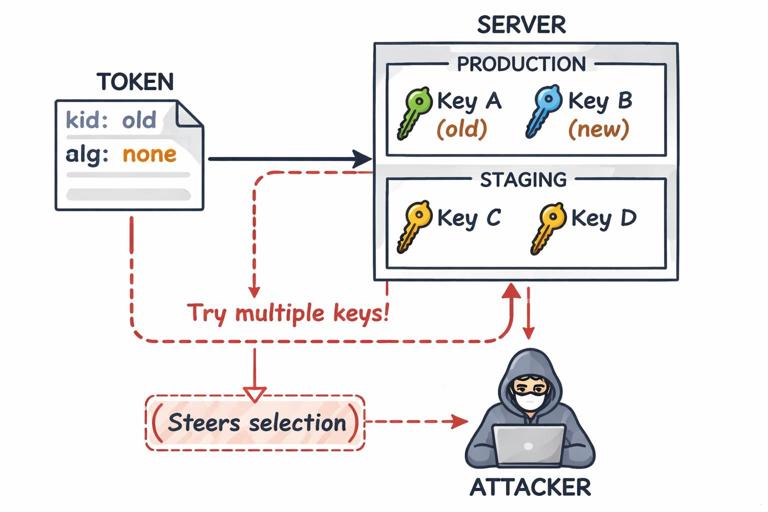

What goes wrong: Systems often support multiple algorithms, key versions, or tenants. A common production failure is “confusion”: verifying a signature with the wrong key, decrypting with a fallback key, or accepting tokens/certificates from the wrong environment (staging vs production). Confusion bugs are especially dangerous because they can become authentication bypasses.

Step-by-step: A typical key confusion incident

- Step 1 — Introduce key rotation: you add key IDs (kid) and keep old keys for a grace period.

- Step 2 — Add fallback logic: “If verification fails, try the previous key” to reduce outages.

- Step 3 — Accept untrusted metadata: the client supplies kid, algorithm, or issuer fields that influence which key is used.

- Step 4 — An attacker crafts inputs: they choose a kid that points to a weaker or unintended key, or they exploit a parsing discrepancy to make the server select a different verification path.

- Step 5 — Verification succeeds incorrectly: the system authenticates the attacker while logs show “signature verified.”

Practical mitigations

Bind identity to key selection: Key choice should be derived from trusted server-side context (tenant ID, environment, issuer) rather than client-controlled fields. If you must read kid, treat it as a lookup hint, not an authority.

Fail closed, not “try everything”: Avoid broad fallback loops. If you support multiple keys, verify against the expected key set for that context only. If verification fails, return an error rather than searching for a key that makes it pass.

// Pseudocode: key selection bound to tenant and issuer, not just kid. expectedIssuer = tenantConfig.issuer keySet = tenantConfig.keySet // server-side trusted if token.issuer != expectedIssuer: reject key = keySet.lookup(token.kid) if key == null: reject if !verify(token, key): rejectFailure Case 3: Serialization, Canonicalization, and Parsing Mismatches

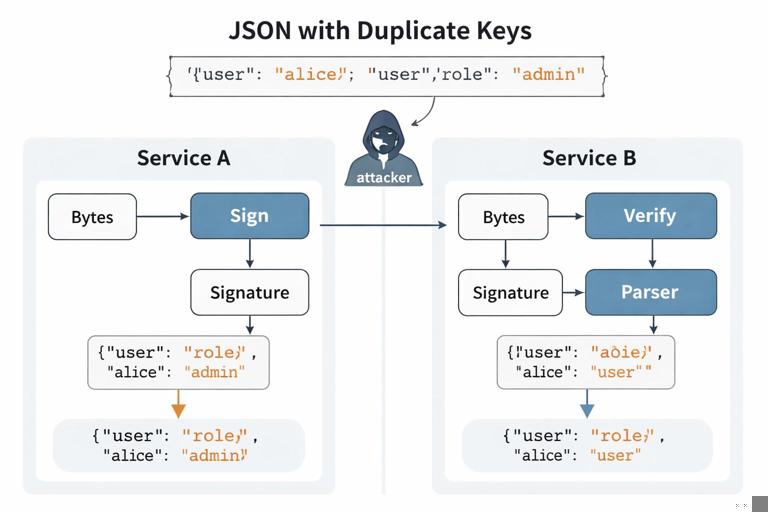

What goes wrong: Crypto often signs or MACs “bytes,” but applications think in terms of objects: JSON, protobuf, query strings, headers. If the producer and verifier do not agree on a canonical byte representation, attackers can create two different interpretations of “the same” message: one that verifies and one that the application processes differently.

Common production sources of mismatch

- JSON ambiguity: whitespace, key ordering, duplicate keys, numeric formats (1 vs 1.0), Unicode normalization.

- HTTP normalization: header folding, case-insensitive header names, multiple headers with same name, proxy rewriting.

- URL/query parsing: “+” vs “%20”, repeated parameters, different decoding rules across services.

- Cross-language differences: one service uses a library that preserves duplicate JSON keys; another keeps the last key only.

Step-by-step: A signature bypass via parsing differences

- Step 1 — Service A signs a JSON payload: it serializes an object to JSON and signs the resulting bytes.

- Step 2 — Service B verifies then parses: it verifies the signature over the raw bytes, then parses JSON into an object.

- Step 3 — Attacker crafts “weird but valid” JSON: e.g., duplicate keys: {"role":"user","role":"admin"}.

- Step 4 — Signature verifies: bytes match what was signed (or the attacker gets something signed in a workflow).

- Step 5 — Parser chooses a different semantic meaning: Service B keeps the last key and treats role as admin.

Practical mitigations

Sign a canonical form: Use a canonical serialization format with strict rules, or sign a stable encoding like protobuf with deterministic serialization enabled. If you must use JSON, enforce a canonical JSON scheme and reject non-canonical inputs.

Verify what you use: Perform parsing first into a strict internal representation, then re-serialize canonically and verify the signature over that canonical representation (or compute the MAC over the canonical representation). This reduces “verify bytes, use different bytes” bugs.

// Pseudocode: strict parse + canonicalize before verify. obj = strictParseJSON(inputBytes) canonical = canonicalJSON(obj) if !verify(signature, canonical): reject process(obj)Failure Case 4: Time, Clock Skew, and Replay Windows

What goes wrong: Production systems rely on time for expiry, freshness, and replay protection. But clocks drift, NTP steps time backward, containers inherit incorrect time, and distributed systems observe events out of order. Crypto mechanisms that assume “time is reliable” can fail open (accept expired tokens) or fail closed (lock out legitimate users), and both can be exploitable.

Step-by-step: Replay protection that fails under skew

- Step 1 — You add a timestamp to requests: client sends ts and a MAC/signature over (ts || request).

- Step 2 — Server accepts within a window: e.g., ±5 minutes to tolerate skew.

- Step 3 — Load balancer routes to multiple servers: each server has slightly different time and different replay caches.

- Step 4 — Attacker replays within the window: they send the same request to different servers that don’t share replay state.

- Step 5 — Duplicate actions occur: double withdrawals, repeated password reset emails, duplicated purchases.

Practical mitigations

Use idempotency keys and server-side replay state: For state-changing operations, require an idempotency key and store it in a shared datastore with a TTL. Cryptographic freshness signals should be backed by shared state when the action matters.

Design for monotonicity: Use monotonic clocks for measuring durations; treat wall-clock time as untrusted input. When validating expiry, consider “not before” and “not after” with explicit skew allowances, and log skew anomalies.

// Pseudocode: shared replay protection for a signed request. if !verify(sig, requestBytes): reject if replayStore.exists(request.idempotencyKey): return previousResult replayStore.put(request.idempotencyKey, ttl=10m) result = executeAction(request) replayStore.update(request.idempotencyKey, result) return resultFailure Case 5: Side Channels in Real Systems (Not Just Academic)

What goes wrong: Side channels appear when secret-dependent behavior leaks through timing, error messages, response sizes, cache behavior, or observable retries. In production, the most common side channels are not CPU cache attacks; they are “API tells you too much” and “different errors for different failures.”

Concrete examples you can test for

- Padding/format oracles: different error codes for “bad padding” vs “bad MAC” vs “bad JSON.”

- Token probing: “unknown kid” vs “signature invalid” reveals which keys exist.

- User enumeration: “email not found” vs “wrong password” (even if passwords are stored safely, the protocol leaks identity existence).

- Timing differences: early returns on first mismatch in MAC compare, or different code paths for different tenants.

Practical mitigations

Unify error handling: Return a single generic error for authentication/verification failures. Log detailed reasons internally with rate limits and careful access controls.

Constant-time comparisons where appropriate: Use constant-time equality for MACs, tokens, and secret values. Don’t implement your own; use vetted library functions.

// Pseudocode: constant-time compare and generic error. if !constantTimeEqual(expectedMac, providedMac): rejectGenericAuthError()Failure Case 6: Key Lifecycle and Operational Leakage

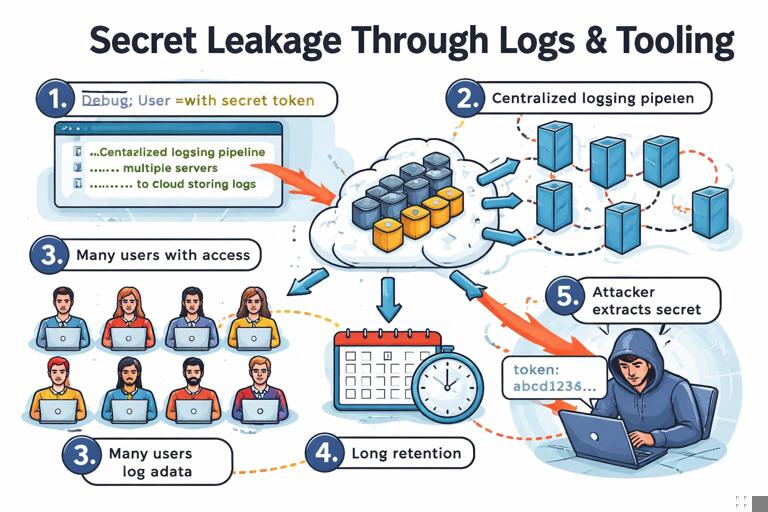

What goes wrong: Even with correct algorithms, keys leak through operational channels: logs, crash dumps, metrics labels, debug endpoints, support tickets, CI artifacts, backups, or misconfigured object storage. Another common failure is “keys live too long”: old keys remain valid indefinitely, or decommissioned environments still accept production credentials.

Step-by-step: How keys end up in logs

- Step 1 — Add debug logging during an incident: log “request context” or “decrypted payload” to troubleshoot.

- Step 2 — Logs are shipped centrally: to a third-party log platform or shared cluster.

- Step 3 — Access expands: more engineers, contractors, or support roles can query logs.

- Step 4 — Sensitive material persists: retention policies keep logs for months.

- Step 5 — Attacker obtains log access: via account takeover, SSRF to metadata endpoints, or misconfiguration, and extracts secrets.

Practical mitigations

Redaction by default: Implement structured logging with field-level redaction. Treat decrypted data, raw tokens, private keys, and session secrets as “never log.” Add automated tests that scan logs in CI for patterns (e.g., PEM headers, JWT-like strings).

Short validity and revocation paths: Ensure you can revoke keys and credentials quickly. Rotation is not just generating new keys; it’s also removing trust in old keys and verifying that old environments can’t still authenticate.

Failure Case 7: Dependency and Configuration Drift

What goes wrong: Production differs from development: FIPS mode toggles, OpenSSL versions differ, JVM security providers change, container images pin old libraries, or a reverse proxy terminates TLS and forwards plaintext internally. Crypto breaks when assumptions about the runtime environment are wrong.

Step-by-step: A drift-driven outage or vulnerability

- Step 1 — You deploy a new service version: it uses a newer crypto API or expects a certain provider.

- Step 2 — One region runs an older base image: missing ciphers, different defaults, or different certificate stores.

- Step 3 — Fallback behavior kicks in: weaker algorithms, disabled verification, or “accept self-signed in non-prod” accidentally enabled.

- Step 4 — Only some traffic is affected: making it hard to detect and easy to exploit selectively.

Practical mitigations

Pin and attest runtimes: Use reproducible builds, pinned base images, and dependency scanning. Record crypto-relevant runtime facts at startup (provider versions, enabled modes) and alert on changes.

Make insecure modes impossible to enable accidentally: Separate configuration for development vs production should be enforced by build-time flags or deployment policy, not by a boolean in a shared config file.

Failure Case 8: Multi-Tenant and Cross-Environment Boundary Failures

What goes wrong: In multi-tenant systems, the cryptographic boundary must align with the authorization boundary. Production failures occur when a key is shared across tenants unintentionally, when tenant identifiers are not bound to signatures/MACs, or when staging and production share trust roots.

Step-by-step: Cross-tenant data exposure via missing binding

- Step 1 — Encrypt tenant data with a “service key”: for simplicity, one key for all tenants.

- Step 2 — Store ciphertexts in a shared database: keyed by tenant_id and record_id.

- Step 3 — An authorization bug leaks a ciphertext: tenant A can fetch tenant B’s ciphertext due to an IDOR or query bug.

- Step 4 — Decryption succeeds: because the same key works for all tenants.

- Step 5 — Confidentiality is lost across tenants: crypto provided no compartmentalization.

Practical mitigations

Compartmentalize keys: Use per-tenant keys or envelope encryption with tenant-specific wrapping keys. Bind tenant identity into associated data (AAD) so ciphertexts cannot be replayed across tenants without detection.

// Pseudocode: bind tenantId as AAD for AEAD. aad = encode("tenant:") || tenantId ciphertext = AEAD_Encrypt(tenantKey, nonce, plaintext, aad) // On decrypt, require same aadFailure Case 9: Backups, Snapshots, and “Undelete” of Secrets

What goes wrong: Production systems create backups, snapshots, and replicas. If secrets are present in those artifacts, “deleting” a key or revoking access may not remove it from historical copies. Attackers target backups because they are often less monitored and more broadly accessible.

Practical steps to reduce backup-related crypto failures

- Encrypt backups with separate keys: do not reuse the same keys used for live data paths.

- Control access tightly: backups should have stricter access than production databases, not looser.

- Test restore paths: ensure restored environments don’t come up with production trust, credentials, or outbound access.

- Plan for key compromise: know which backups become readable if a given key leaks, and how you would rotate and re-encrypt.

Failure Case 10: Observability, Debuggability, and the “Security Tax”

What goes wrong: Teams add instrumentation to understand systems: tracing, metrics, sampling, request/response capture. These tools can undermine crypto by capturing plaintext, headers, tokens, or decrypted payloads. Another failure is disabling verification “temporarily” to reduce alert noise, then forgetting to re-enable it.

Step-by-step: How tracing captures secrets

- Step 1 — Enable distributed tracing: capture HTTP headers and bodies for debugging.

- Step 2 — Sampling increases during an incident: more data is captured.

- Step 3 — Sensitive fields are included: Authorization headers, cookies, signed URLs, reset tokens.

- Step 4 — Traces are stored and shared: across teams and vendors.

- Step 5 — Tokens are replayed: attackers or insiders use captured secrets to impersonate users or services.

Practical mitigations

Secret-aware instrumentation: Configure tracing to drop or hash sensitive headers and fields. Implement allowlists (only capture known-safe fields) rather than blocklists (which miss new secrets).

Guardrails for “temporary” insecure changes: Use feature flags with expiration, require approvals for disabling verification, and alert when verification is off. Treat “verification disabled” as a production incident.

How to Diagnose Crypto Failures Without Guessing

Build a failure-focused checklist: When something looks like a crypto issue, don’t start by changing algorithms. Start by checking invariants: nonce uniqueness, key selection context, canonicalization, time assumptions, environment drift, and secret leakage paths.

Practical step-by-step triage workflow

- Step 1 — Reproduce with captured inputs: capture the exact bytes (request body, headers, token) in a secure way. Avoid copying secrets into tickets; use a secure vault or redacted artifacts.

- Step 2 — Verify invariants: confirm which key ID/version was used, which algorithm/provider, and whether the same bytes were verified and later parsed/used.

- Step 3 — Check time and state: compare server clocks, look for NTP steps, restarts, autoscaling events, and replay cache behavior.

- Step 4 — Compare environments: library versions, FIPS mode, container images, proxy behavior, certificate stores.

- Step 5 — Look for “helpful” fallbacks: any code that retries with different keys, different algorithms, or relaxed verification.

// Minimal diagnostic logging pattern (structured, redacted). log.info({ event: "verify_failed", tenant: tenantId, key_id: kid, alg: alg, provider: cryptoProviderVersion, reason: "generic" })