Why ethics belongs inside causal inference (not after it)

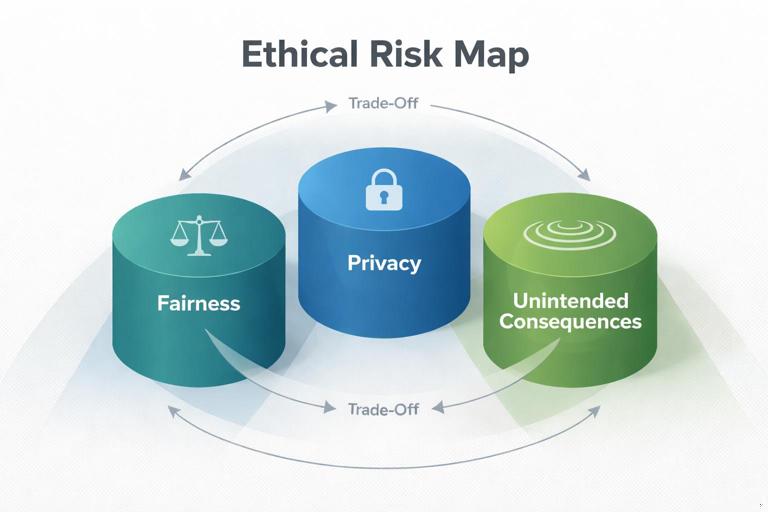

Causal inference is often introduced as a way to answer “What happens if we do X?” Ethically, the question is bigger: “What happens to whom, under what constraints, and at what cost?” Ethical causal inference treats fairness, privacy, and unintended consequences as first-class design requirements—alongside statistical validity and business impact.

In practice, ethics shows up in three places: (1) how you define the decision and success metrics, (2) how you collect and use data, and (3) how you deploy and monitor the resulting policy. Causal methods can reduce harm by clarifying trade-offs and preventing misleading correlations from driving decisions, but they can also amplify harm if you optimize the wrong objective, ignore distributional impacts, or collect data in invasive ways.

Ethical risk map: fairness, privacy, and unintended consequences

Fairness risks

Disparate impact from a “neutral” treatment: A policy may raise average outcomes while harming a subgroup.

Unequal access to treatment: Eligibility rules, targeting, or rollout constraints can systematically exclude groups.

Measurement inequity: Outcomes and labels (e.g., “fraud,” “quality,” “engagement”) may be noisier or biased for some groups, leading to distorted effect estimates.

Continue in our app.- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Feedback loops: Decisions change the data-generating process (e.g., more policing leads to more recorded crime), which can create self-fulfilling patterns.

Privacy risks

Over-collection: Gathering sensitive attributes “just in case” increases exposure without clear benefit.

Re-identification: Even if direct identifiers are removed, combinations of features can identify individuals.

Secondary use: Data collected for one purpose is reused for another without appropriate consent or governance.

Inference attacks: Models can leak information about individuals (membership inference, attribute inference), especially when trained on small or unique cohorts.

Unintended consequence risks

Goodhart’s law: When a metric becomes a target, it stops being a good metric. Optimizing a proxy can degrade the true goal.

Behavioral adaptation: Users, employees, or counterparties change behavior in response to the policy (gaming, avoidance, strategic compliance).

Spillovers and displacement: Benefits in one area can push harm elsewhere (e.g., shifting support load, moving fraud to another channel).

Long-term effects: Short-term gains can create long-term harm (burnout, churn, reduced trust).

Fairness in causal terms: effects, not just predictions

Many fairness discussions focus on predictive models (e.g., equal error rates). Causal inference reframes fairness around interventions: “If we apply this policy, do outcomes improve equitably?” This matters because a model can be “fair” by some predictive metric yet still produce unfair outcomes when deployed as a decision rule.

Key fairness questions that are causal

Average effect by group: Does the treatment help one group more than another? Are any groups harmed?

Fair access: Who receives the treatment under the policy, and who is systematically excluded?

Counterfactual fairness (conceptual): Would the decision change for an individual if a sensitive attribute were different, holding everything else constant? This is a demanding standard and often not fully testable, but it is useful as a design lens.

Practical approach: distributional reporting, not just a single number

Ethical causal reporting should include more than an overall effect estimate. At minimum, report effects across relevant subgroups and include uncertainty. If subgroup sample sizes are small, avoid overconfident claims; instead, treat subgroup analysis as a risk scan and plan targeted data collection or staged rollouts.

# Example reporting template (pseudo-output, not code execution):

Overall effect on outcome: +1.8% (95% CI: +0.9% to +2.7%)

Group A effect: +2.4% (CI: +1.0% to +3.8%)

Group B effect: +0.2% (CI: -1.5% to +1.9%)

Group C effect: -1.1% (CI: -3.0% to +0.8%)

Flag: potential harm for Group C; require mitigation before full rolloutStep-by-step: an ethical checklist for causal projects

Step 1: Define the ethical objective alongside the business objective

Write down the business goal and the ethical constraints in plain language. Ethical constraints are not vague values; they should be operationalizable.

Business objective: “Reduce customer support wait time.”

Ethical constraints: “Do not increase abandonment for non-native speakers,” “Do not reduce access for customers with disabilities,” “Do not collect new sensitive attributes.”

Translate constraints into measurable guardrails: subgroup-specific thresholds, complaint rates, accessibility metrics, or opt-out rates.

Step 2: Identify who could be harmed and how

Create a harm inventory. Include direct harms (worse outcomes) and indirect harms (loss of autonomy, privacy intrusion, stigmatization).

Stakeholders: customers, employees, vendors, communities, regulators.

Harm channels: denial of service, price discrimination, increased surveillance, reduced transparency, manipulation, safety risks.

Step 3: Choose sensitive attributes and proxies carefully

Fairness analysis often requires sensitive attributes (e.g., age band, disability status) to detect disparities. Privacy and legal constraints may limit collection. If you cannot measure sensitive attributes, be explicit about what you can and cannot claim. Avoid pretending fairness is guaranteed because you “didn’t use” sensitive features—proxies can recreate them.

Practical compromise patterns:

Use coarse categories: age bands instead of exact birthdate.

Use voluntary, purpose-limited collection: collect only for fairness auditing with strict access controls.

Use privacy-preserving aggregation: compute group metrics in a secure environment and export only aggregates.

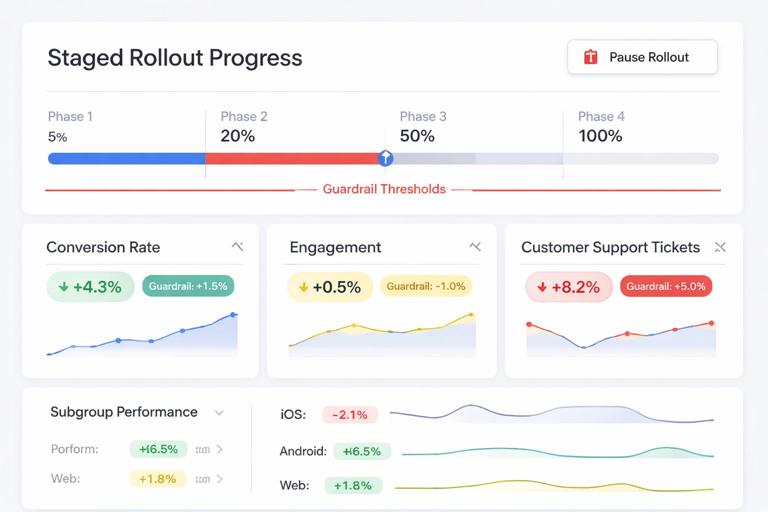

Step 4: Design the evaluation to detect harm early

Ethical evaluation emphasizes early warning. Use staged rollouts and guardrails that can stop or reverse deployment if harm appears.

Predefine harm thresholds: e.g., “If any protected group’s outcome drops by more than 0.5% relative to baseline, pause rollout.”

Use multiple time horizons: short-term and medium-term checks to catch delayed effects.

Monitor distributional shifts: not only mean outcomes; look at tails (e.g., worst 5% experience).

Step 5: Document assumptions and decision rights

Ethical causal inference requires accountability. Maintain a short “decision record” that includes: intended use, excluded uses, data sources, key assumptions, known limitations, and who can approve changes. This is especially important when models or policies will be reused beyond the original context.

Fairness patterns in experiments and policy rollouts

Pattern 1: Averages hide harm

Scenario: A new recommendation algorithm increases overall engagement. However, it decreases engagement for new users in a specific region because content becomes less locally relevant.

Ethical causal response: Treat subgroup harm as a first-order outcome. Options include: (a) restrict rollout for the harmed subgroup, (b) adjust the algorithm to include local relevance constraints, (c) create a separate policy for that subgroup if justified and lawful.

Pattern 2: Eligibility rules create unfair access

Scenario: A retention offer is given only to customers with high predicted churn. If the churn model underestimates churn for a subgroup (due to measurement issues), that subgroup receives fewer offers.

Ethical causal response: Evaluate not only the effect of the offer but also the effect of the targeting rule on access. Consider auditing the targeting pipeline: who is eligible, who is selected, and whether selection aligns with need.

Pattern 3: Interventions can change the meaning of the outcome

Scenario: A fraud-prevention step reduces chargebacks (measured outcome) but increases false declines, pushing legitimate customers away. Chargebacks fall, but trust and long-term revenue decline.

Ethical causal response: Add outcomes that capture customer harm (false decline rate, complaint rate, repeat purchase). Treat them as guardrails, not optional secondary metrics.

Privacy-aware causal inference: data minimization and safe measurement

Privacy is not only about compliance; it is about reducing unnecessary exposure while still enabling reliable decisions. Causal projects often tempt teams to collect more data to “control for everything.” Ethical practice pushes the opposite direction: collect the minimum needed to answer the question, and prefer designs that reduce reliance on sensitive individual-level data.

Data minimization checklist (practical)

Purpose specification: What decision will this data support? What will it not be used for?

Field-level justification: For each feature, write why it is needed and what risk it introduces.

Retention limits: Keep raw data only as long as needed for analysis and auditing.

Access controls: Separate duties (analysts vs. engineers vs. approvers), log access, and review permissions.

Aggregation first: When possible, compute metrics in aggregate rather than exporting row-level data.

Privacy-preserving techniques commonly used in causal work

Pseudonymization and secure joins: Use stable hashed IDs and perform joins in controlled environments to reduce exposure.

Differential privacy for reporting: Add calibrated noise to published metrics so individuals cannot be inferred from outputs. This is especially relevant when reporting subgroup effects on small cohorts.

Federated or on-device measurement (when feasible): Keep raw behavioral data on-device and send only aggregates or model updates.

Synthetic data for development: Use synthetic datasets for pipeline testing; reserve real data for final analysis in secure contexts.

Important practical note: privacy techniques can reduce statistical power or introduce bias if applied naively (e.g., heavy noise on small groups). Treat privacy as a design parameter and plan sample sizes and reporting granularity accordingly.

Unintended consequences: causal thinking beyond the primary outcome

Unintended consequences are often causal effects on outcomes you did not prioritize. Ethical practice requires anticipating them and measuring them explicitly.

Common unintended consequence categories (with examples)

Risk shifting: A safety feature reduces incidents in one category but increases them elsewhere (e.g., fewer account takeovers but more social engineering attempts).

Burden shifting: Automation reduces cost but increases employee cognitive load or customer effort.

Equity regressions: A policy improves average service speed but increases variance, making the worst experiences worse.

Trust erosion: Aggressive personalization increases short-term conversion but triggers “creepy” perceptions and opt-outs.

Step-by-step: building a guardrail metric set

Guardrails are metrics that, if degraded, indicate harm even if the primary metric improves. Build them systematically:

Step 1: List stakeholders and what “harm” looks like for each (customers: unfair denial; employees: burnout; business: regulatory risk).

Step 2: For each harm, define a measurable proxy (complaints, opt-outs, refund rates, accessibility failures, error rates).

Step 3: Set thresholds and escalation paths before running the intervention.

Step 4: Ensure guardrails are measured with the same rigor as the primary outcome (instrumentation, latency, subgroup cuts).

Step 5: Decide what action is triggered (pause, rollback, mitigation experiment, narrower targeting).

# Example guardrail table (conceptual)

Primary outcome: conversion rate

Guardrails:

- Refund rate (overall and by region)

- Customer support contacts per order

- Opt-out / unsubscribe rate

- Accessibility error rate (screen reader failures)

- Subgroup outcome floors (no group below -0.5% relative change)Ethical pitfalls specific to causal workflows

Pitfall: “Fairness through unawareness”

Not using sensitive attributes does not guarantee fairness. If other variables act as proxies (zip code, device type, browsing patterns), the policy can still create disparate impact. Ethical practice requires auditing outcomes by group, not only auditing inputs.

Pitfall: Biased measurement of the outcome

If the outcome is recorded differently across groups, estimated effects can be misleading. Example: “customer satisfaction” measured via survey responses may underrepresent groups with lower response rates or language barriers. Practical mitigation includes alternative measurement channels, weighting adjustments for response propensity, and triangulation with behavioral indicators.

Pitfall: Selective reporting of subgroup results

Teams may highlight favorable subgroup effects and downplay harms. Prevent this by predefining which subgroup cuts will be reported and by using a standard reporting template that always includes both benefits and harms.

Pitfall: Overreacting to noisy subgroup estimates

Small subgroups can produce wide uncertainty. Ethical practice is not to ignore them, but to treat uncertainty as risk: consider protective rollouts, targeted data collection, or conservative policies until evidence improves.

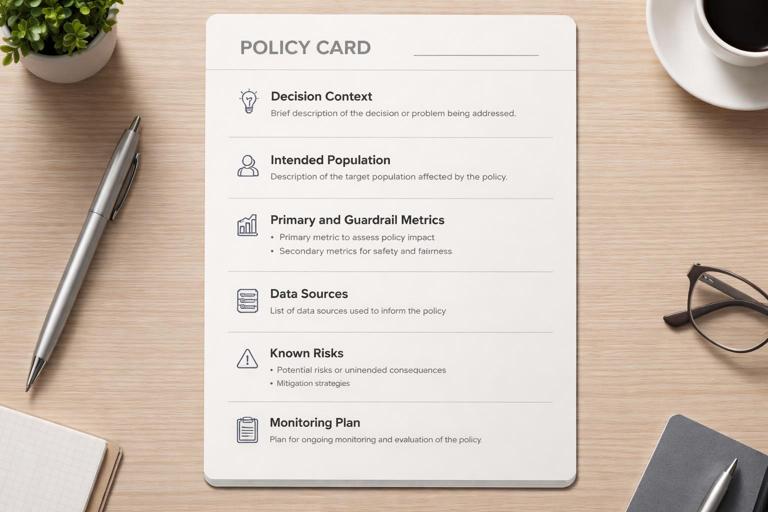

Practical governance: making ethical causal inference repeatable

Model/policy cards for interventions

Create a lightweight document for each intervention that includes:

Decision context: what decision is being automated or supported.

Intended population: who is in scope and who is out of scope.

Primary and guardrail metrics: including subgroup definitions.

Data sources: what is collected, retention, and access controls.

Known risks: fairness, privacy, and unintended consequences.

Monitoring plan: dashboards, alert thresholds, rollback plan.

Decision review and escalation

Ethical issues often require cross-functional judgment. Define who can approve: product owner, data science lead, privacy officer, legal/compliance, and an operational owner who can execute rollbacks. Establish an escalation path when guardrails trigger.

Worked example: ethically evaluating a targeted discount policy

Scenario: A company wants to offer targeted discounts to reduce churn. The treatment is “receive a discount offer.” The outcome is “retained after 60 days.” Ethical concerns: price discrimination perceptions, unfair exclusion, and privacy risks from using detailed behavioral data.

Step-by-step ethical plan

1) Define constraints: No subgroup should experience a retention decrease; discount targeting must not use sensitive attributes directly; do not collect new sensitive data.

2) Harm inventory: customers may feel manipulated; some may pay more than others; vulnerable groups may be excluded; increased support contacts due to confusion.

3) Data minimization: use existing account tenure and product usage aggregates; avoid granular clickstream if not needed; restrict access to targeting features.

4) Guardrails: complaint rate, opt-out rate, net revenue (to detect unsustainable discounting), subgroup retention floors, and “perceived fairness” survey for a sample.

5) Rollout strategy: staged rollout with a small initial fraction; monitor guardrails daily; pause if any subgroup floor is violated.

6) Reporting: publish a standard table of overall and subgroup effects, plus guardrail movements, with uncertainty intervals and a clear decision recommendation.

Ethical trade-offs: when fairness and privacy pull in different directions

Fairness auditing may require collecting sensitive attributes; privacy principles push you to collect less. Handle this tension explicitly:

Prefer voluntary disclosure: allow users to self-report for fairness auditing with clear purpose and benefits.

Use secure enclaves: keep sensitive attributes in a restricted environment; export only aggregated fairness metrics.

Limit granularity: avoid overly fine subgroup slicing that risks re-identification.

Time-bound audits: collect sensitive attributes for a limited audit window, then delete or heavily restrict.

When you cannot measure sensitive attributes at all, be honest: you can still monitor for broad harms (e.g., by geography or language settings), but you cannot claim protected-group fairness without measurement.

Operational monitoring: ethics after deployment

Ethical causal inference does not stop at estimating an effect. Once deployed, the environment changes: user behavior adapts, competitors respond, and the policy may drift. Monitoring should include:

Outcome drift: the effect size changes over time.

Distribution shift: the treated population changes (e.g., new user mix).

Fairness drift: subgroup effects diverge as conditions change.

Privacy incidents: unexpected data flows, access anomalies, or new linkage risks.

Set up alerts that are actionable: who gets paged, what decision they can make, and what rollback mechanism exists. Ethics is operational when the organization can actually stop harm quickly.