Why outcomes, interests, and boundaries matter in non-sales negotiations

In non-sales roles, negotiation often looks like prioritization, scope decisions, resourcing, timelines, risk acceptance, and cross-team commitments. The fastest way for these discussions to become frustrating is to enter them with only a vague desire ("I need this done") or a single position ("We must ship by Friday"). Defining outcomes, interests, and boundaries gives you a structured way to clarify what you are trying to achieve, why it matters, and what you can and cannot accept. This clarity improves your ability to propose trade-offs, evaluate options quickly, and avoid accidental commitments.

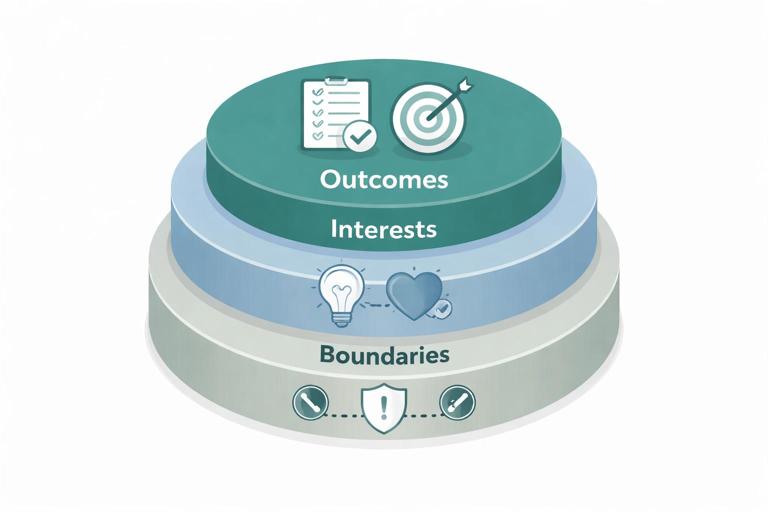

Think of these three elements as different layers of the same negotiation:

- Outcomes: the concrete results you want to walk away with (deliverables, decisions, commitments, timelines, quality levels).

- Interests: the underlying needs, motivations, constraints, and risks that make those outcomes valuable.

- Boundaries: the limits that define what is acceptable (minimum requirements, non-negotiables, legal/compliance constraints, capacity realities, and walk-away points).

When you define all three, you can negotiate with precision: you know what success looks like, you can explain the “why” in a way that invites collaboration, and you can protect yourself and your team from over-commitment.

Defining outcomes: what “done” looks like

An outcome is a specific, observable end state. In workplace negotiations, outcomes are often multi-part: a decision plus a timeline plus responsibilities plus acceptance criteria. If you only define the timeline, you may end up with a rushed deliverable that fails quality checks. If you only define the deliverable, you may end up with no owner or no deadline.

Common outcome categories in non-sales roles

- Scope outcomes: what is included/excluded, what is “phase 1” vs “later.”

- Time outcomes: dates, milestones, response times, meeting cadence.

- Quality outcomes: acceptance criteria, testing requirements, review steps, definition of “ready.”

- Resource outcomes: headcount allocation, budget, tooling, access to subject matter experts.

- Decision outcomes: who decides, by when, with what input, and how disagreements are resolved.

- Risk outcomes: what risks are accepted, mitigated, or escalated; what monitoring is required.

Outcome statements: make them measurable

A useful outcome statement is measurable and time-bound. Compare:

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

- Vague: “We need better reporting.”

- Clear: “By the 15th, we will deliver a weekly dashboard that shows pipeline volume, conversion rate, and cycle time by segment, refreshed every Monday by 10 a.m., with access for Finance and RevOps.”

Clarity reduces hidden disagreements. If someone says “yes” to “better reporting,” they may imagine a one-time spreadsheet; you may imagine an automated dashboard with governance and definitions.

Practical step-by-step: outcome definition worksheet

Before the conversation, write a one-page outcome worksheet:

- 1) Primary outcome: What is the single most important result? (One sentence.)

- 2) Secondary outcomes: What else would make this successful? (3–5 bullets.)

- 3) Acceptance criteria: How will we know it meets the need? (List checks or metrics.)

- 4) Timeline: What is the target date and the latest acceptable date?

- 5) Owners: Who owns delivery, review, approval, and ongoing maintenance?

- 6) Dependencies: What must happen first, and who controls it?

Then translate the worksheet into a short “ask” you can say in a meeting. Example:

Ask: “Can we align today on a phase-1 deliverable: a weekly dashboard with these three metrics, refreshed Mondays by 10 a.m., delivered by the 15th, with RevOps owning maintenance and Finance approving definitions by next Wednesday?”Defining interests: why the outcome matters

Interests are the drivers behind your outcomes. They include business goals (reduce churn), personal or team goals (avoid weekend work), constraints (limited engineering capacity), and risk considerations (compliance exposure). Interests are not “soft”; they are the logic that makes trade-offs possible. If you can explain your interests, the other party can propose alternative outcomes that still satisfy what you truly need.

How interests differ from positions

A position is what you say you want. An interest is why you want it. Positions tend to collide; interests can be reconciled.

- Position: “We need this feature in the next sprint.”

- Interests: “We have a customer renewal tied to it, and we need a credible plan to reduce churn risk without burning out the team.”

Once interests are visible, options expand: maybe the renewal risk can be handled with a workaround, a partial release, a customer communication plan, or a temporary manual process.

Interest types to surface explicitly

- Business impact: revenue protection, cost reduction, customer experience, operational efficiency.

- Risk and compliance: legal requirements, security standards, auditability, reputational risk.

- Capacity and sustainability: workload, on-call stability, cognitive load, competing priorities.

- Quality and reliability: defect rates, performance, maintainability, support burden.

- Stakeholder expectations: executive commitments, external deadlines, partner dependencies.

- Fairness and reciprocity: perceived balance of effort, avoiding one-sided “favors.”

Practical step-by-step: the “Five Whys for negotiation”

To uncover your own interests, run a short “why” chain on each key outcome. Keep it grounded in work realities rather than abstract values.

- 1) Write the outcome: “Launch the policy update by March 1.”

- 2) Ask why it matters: “Because the current policy creates inconsistent approvals.”

- 3) Ask why that matters: “Because inconsistency increases audit findings and escalations.”

- 4) Ask why that matters: “Because audit findings trigger remediation work and leadership scrutiny.”

- 5) Summarize the interest: “We need consistency to reduce audit risk and prevent reactive remediation.”

Now you can negotiate alternatives: if March 1 is hard for another team, perhaps you can implement a narrower rule set by March 1 and a full update later, as long as the audit-risk drivers are addressed.

Practical example: negotiating with IT for access

Scenario: You are in Analytics and need access to a production dataset. IT is reluctant due to security concerns.

- Your outcome: “Read-only access to dataset X for the analytics team by next week.”

- Your interests: “We need timely insights for a leadership review; delays create decision risk. We also need a repeatable process so we don’t request ad hoc access every month.”

- IT’s likely interests: “Prevent data leakage, maintain least-privilege access, ensure audit trails, avoid setting a precedent that increases risk.”

With interests on the table, you can propose options: read-only access through a governed view, time-bound access, access via a secure analytics environment, or a service account with logging. You are no longer stuck arguing “access vs no access”; you are negotiating “insight speed vs security risk” with multiple ways to balance them.

Defining boundaries: what you will not accept

Boundaries are your limits. They protect you from agreeing to outcomes that create unacceptable risk, violate policy, or overload your team. Boundaries also make you more credible: when you can clearly state what is and is not possible, others can plan realistically.

Boundaries are not the same as being inflexible. They are the conditions under which flexibility is safe. The goal is to be explicit early, so you do not discover conflicts after commitments are made.

Types of boundaries

- Minimum acceptable outcome: the least you can accept and still meet the core need.

- Non-negotiables: compliance rules, safety requirements, contractual obligations, ethical standards.

- Capacity boundaries: maximum hours, staffing limits, on-call constraints, competing deadlines.

- Quality boundaries: no release without testing, no policy without legal review, no data access without logging.

- Authority boundaries: what you can approve vs what must be escalated.

- Time boundaries: latest acceptable decision date, freeze periods, blackout windows.

Boundaries vs threats: how to communicate them

A boundary is most effective when framed as a constraint and paired with a path forward. Compare:

- Threat-like: “If you don’t do this, we’re not helping.”

- Boundary-based: “We can’t commit to a Friday launch without QA sign-off; if Friday is fixed, we can reduce scope to these two items and schedule the rest for next sprint.”

The second version communicates a limit while preserving collaboration.

Practical step-by-step: set your “walk-away” and “escalation” points

In workplace negotiations, “walking away” often means escalating, deferring, or choosing a different approach rather than ending a relationship. Define these points in advance:

- 1) Identify the unacceptable outcomes: What would create serious harm (risk, burnout, compliance breach, reputational damage)?

- 2) Define the walk-away alternative: If you cannot reach agreement, what will you do? (Escalate to steering committee, delay launch, use a manual workaround, re-prioritize.)

- 3) Set an escalation trigger: What specific condition triggers escalation? (No decision by date X, scope exceeds Y, risk rating above Z.)

- 4) Prepare a neutral escalation script: “We’re not aligned on risk acceptance; let’s bring this to the risk owner for a decision by Thursday.”

This prevents escalation from feeling emotional or personal; it becomes a predefined governance step.

Putting it together: the Outcomes–Interests–Boundaries (OIB) map

The most practical way to prepare is to map your negotiation in a simple structure. This helps you speak clearly, ask better questions, and identify trade-offs quickly.

OIB map template

Outcomes (what we want): 1–3 bullets with measurable details (scope/time/quality/owners) Interests (why it matters): 3–6 bullets (impact, risk, constraints, stakeholders) Boundaries (limits): 3–6 bullets (non-negotiables, minimums, capacity, authority) Trade-offs we can offer: 3–5 bullets (scope, timing, resources, process changes) Questions to uncover their OIB: 5–8 questionsNotice “trade-offs we can offer” is included. Boundaries are not enough; you also need levers you can move. If you cannot offer anything, you are not negotiating—you are requesting.

Questions that reveal the other side’s outcomes, interests, and boundaries

- “What does success look like for you by the end of this month?”

- “Which part of this is most important: speed, cost, or risk reduction?”

- “What constraints are you operating under that I should know about?”

- “What would make this unacceptable from your perspective?”

- “If we can’t do the full scope, what is the minimum viable version?”

- “Who needs to approve this, and what criteria will they use?”

- “What happens if we delay by two weeks—what breaks?”

- “Is there a deadline driven by an external commitment or an internal preference?”

These questions are especially useful in cross-functional work where people may not volunteer constraints until asked.

Practical step-by-step: preparing for a negotiation meeting using OIB

Use this preparation flow when you have a meeting where commitments will be made (roadmap, staffing, policy, vendor selection, incident follow-up, process changes).

Step 1: Draft your outcomes (3 levels)

- Target outcome: what you want most.

- Acceptable outcome: what still works.

- Minimum outcome: the least you can accept without causing harm.

Example (Project Management negotiating timeline):

- Target: “Release by May 15 with full onboarding flow and analytics.”

- Acceptable: “Release by May 15 with onboarding flow; analytics by June 1.”

- Minimum: “Release by May 30 with onboarding flow; no release without security review.”

Step 2: List your interests and rank them

Ranking matters because it tells you what to protect when trade-offs appear. Example interests:

- Reduce churn risk for a renewal cohort (high)

- Maintain on-call stability (high)

- Hit an internal milestone for leadership visibility (medium)

- Improve documentation quality (low)

If documentation is low, you can trade it for speed (for example, commit to a lighter doc now and a fuller one later) without sacrificing core needs.

Step 3: Write boundaries as conditions, not emotions

Convert vague discomfort into explicit conditions:

- Vague: “This feels risky.”

- Boundary: “We cannot deploy without a rollback plan and monitoring alerts configured.”

Convert personal overload into capacity boundaries:

- Vague: “My team is slammed.”

- Boundary: “We can take this on if we drop one of these two tasks or if we get a dedicated reviewer for two hours per week.”

Step 4: Identify your negotiable levers

List what you can adjust without violating boundaries:

- Scope: reduce features, split into phases, remove edge cases

- Time: move non-critical items later, adjust milestones

- Resources: borrow a reviewer, add a temporary contractor, swap priorities

- Process: change approval sequence, add a working session, use templates

- Risk: accept a known limitation with monitoring and a follow-up date

Step 5: Prepare two packages (not single offers)

Instead of proposing one solution, propose two “packages” that each satisfy your interests differently. This invites choice and reduces positional conflict.

Example packages (Operations negotiating with Engineering for automation):

- Package A (speed): “Automate top 3 steps by end of month; Ops provides detailed requirements in 48 hours; Engineering gets a dedicated Ops tester for 2 hours/day.”

- Package B (risk reduction): “Automate full workflow by next quarter; start with instrumentation and error handling this month; Ops commits to cleaning input data weekly.”

Both packages are framed as mutual commitments, not demands.

Practical examples across common non-sales roles

HR / People Ops: negotiating hiring timeline with a hiring manager

Outcome: “Finalize job description and interview panel by Friday; begin sourcing Monday; offer target in 6 weeks.”

Interests: “Speed matters because workload is high; quality matters because a bad hire increases churn and manager time; candidate experience matters for employer brand.”

Boundaries: “No offer without structured interview feedback; compensation must stay within band; panel must include required stakeholders.”

Trade-offs: “If you want faster, we can reduce the number of interview rounds; if you want broader candidate pool, we may need more time or a sourcing budget.”

Finance: negotiating budget with a department lead

Outcome: “Approve $40k tooling budget with monthly reporting and a 90-day review.”

Interests: “Control spend, ensure ROI visibility, avoid surprise overages, support productivity.”

Boundaries: “No multi-year commitment without procurement review; spend must map to an approved cost center; security review required for SaaS.”

Trade-offs: “We can approve a pilot budget now if you agree to usage metrics and a stop/go decision date.”

Product / Engineering: negotiating scope with stakeholders

Outcome: “Deliver core user flow by sprint end; defer advanced settings to next sprint.”

Interests: “Protect reliability, reduce rework, meet a customer commitment, keep team sustainable.”

Boundaries: “No release without performance testing; no new scope added mid-sprint without removing equivalent scope.”

Trade-offs: “We can add one advanced setting if we remove two low-impact UI enhancements and accept a known limitation documented for support.”

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

Pitfall 1: confusing outcomes with tasks

“Schedule a meeting” is a task; “decide on vendor by Thursday with criteria X” is an outcome. If you negotiate tasks, you may complete activity without achieving the result. Always convert tasks into the decision or deliverable they enable.

Pitfall 2: listing interests that are actually positions

“My interest is shipping by Friday” is still a position. Ask what Friday enables (customer promise, regulatory date, internal demo). The more you can articulate the underlying driver, the more options you create.

Pitfall 3: boundaries that are hidden until late

Hidden boundaries create last-minute surprises (“Legal must review,” “We can’t work weekends,” “This requires security approval”). Surface boundaries early, ideally when you first share your outcome, so the other side can plan around them.

Pitfall 4: boundaries without alternatives

“No” without a path forward stalls collaboration. Pair boundaries with at least one alternative that respects them: phased delivery, reduced scope, different resourcing, or escalation to the right decision-maker.

Pitfall 5: failing to align on whose boundaries matter

Some boundaries are personal preferences; others are organizational constraints. Clarify which is which. For example, “I prefer not to meet Fridays” is different from “Finance cannot approve spend without a purchase order.” When you label boundaries accurately, you avoid unnecessary rigidity and focus attention on real constraints.