What “DAX Foundations” Means in a Business-Question Context

DAX (Data Analysis Expressions) is the calculation language in Power BI that turns a modeled dataset into answers. The “foundations” are not a list of functions to memorize; they are a set of mental models and repeatable patterns that help you translate a business question into a measure that returns the right number under the right filters. Business questions usually sound like: “How much did we sell this month?”, “Are we improving versus last year?”, “Which products drive margin?”, “What share of revenue comes from the top customers?”, or “How many customers are new?” DAX foundations help you answer these consistently across visuals, slicers, and drilldowns.

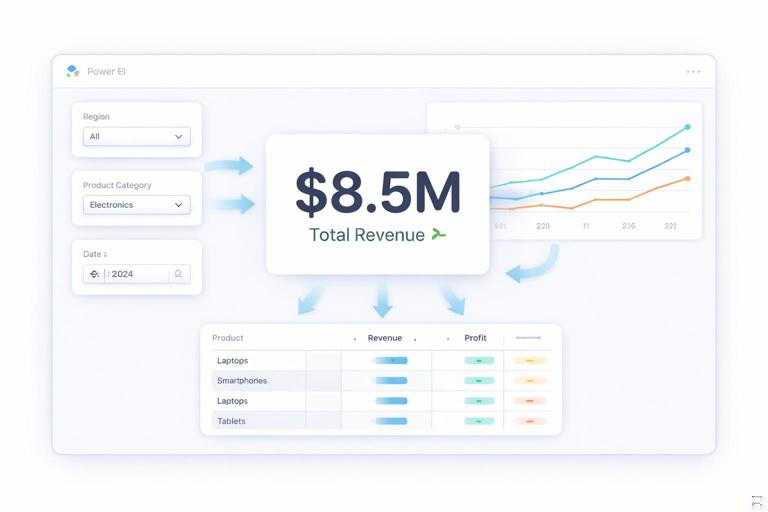

To support business questions, you will primarily use measures (not calculated columns) because measures respond to filter context coming from visuals. A KPI card, a line chart by month, and a matrix by region all need the same measure to behave correctly when the user slices by product, customer segment, or time. The core DAX skill is understanding how filter context is created and how to intentionally modify it to match the question.

Measures vs Calculated Columns: Choosing the Right Tool for the Question

Calculated columns are computed row by row during data refresh and stored in the model. Measures are computed at query time based on the current filter context. Most business questions are aggregations that must change when the user interacts with the report, so measures are the default choice. Use calculated columns when you need a stable attribute for slicing or grouping (for example, a “Customer Tenure Band” or “Is Weekend” flag), but keep numeric business answers as measures.

Practical rule of thumb: if the number should change when you click a bar in a chart or select a slicer, it should be a measure. If the value is a property of a single row (or a single entity) that does not depend on the report filters, it can be a calculated column.

Filter Context and Row Context: The Two Contexts You Must Control

Filter context is the set of filters applied to a calculation: slicers, visual axes, page filters, report filters, and cross-filtering from other visuals. When you place a measure in a visual, Power BI evaluates it once per cell using that cell’s filter context. This is why the same measure can show different values across months, regions, or products.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Row context exists when DAX iterates over rows, typically in calculated columns or iterator functions like SUMX, AVERAGEX, MINX, and MAXX. Row context is “current row” awareness. Many business questions require iterating over a table (for example, summing line-level margin or counting customers with a condition), so you need to understand when you are in row context and when you are not.

A common foundation concept is context transition: when CALCULATE is used inside a row context, it converts the current row into an equivalent filter context. This is crucial for patterns like “sum of per-customer revenue” or “count of customers meeting a threshold.”

Start with Base Measures: The Building Blocks for Every KPI

Executive-ready dashboards rely on a small set of trusted base measures that are reused everywhere. Base measures are simple, additive, and easy to validate. They typically include totals and counts that match accounting or operational definitions. Once base measures are correct, more advanced measures (time intelligence, ratios, segmentation) become safer and faster to build.

Base measure examples

Assume you have a fact table named Sales with columns Sales[SalesAmount], Sales[CostAmount], Sales[Quantity], and an Orders table or Sales[OrderID]. Create base measures like these:

Total Sales = SUM ( Sales[SalesAmount] )Total Cost = SUM ( Sales[CostAmount] )Total Quantity = SUM ( Sales[Quantity] )Order Count = DISTINCTCOUNT ( Sales[OrderID] )These measures are intentionally “boring.” Their value is that they behave predictably under any filter context and can be reconciled to source totals.

CALCULATE: The Most Important Function for Business Questions

CALCULATE changes the filter context for an expression. Most business questions include a condition like “for this year,” “excluding returns,” “only active customers,” “for the selected region but ignoring product,” or “for the last 30 days.” CALCULATE is how you express those conditions in a reusable way.

Example: Sales for Completed Orders Only

If Sales has a status column, you can define a measure that always filters to completed orders:

Sales (Completed) = CALCULATE ( [Total Sales], Sales[Status] = "Completed" )This measure will still respond to slicers for date, product, region, and customer, but it will always enforce Status = Completed. That is a direct translation of a business definition into DAX.

Example: Sales Ignoring Product (for Mix Analysis)

Sometimes you want to compare a product’s sales to the total sales in the same region and time period, ignoring the product filter. That is a classic “share of total” question.

Total Sales (All Products) = CALCULATE ( [Total Sales], ALL ( Product ) )ALL removes filters from the specified table (or column). Used carefully, it lets you compute denominators for shares and benchmarks.

ALL, REMOVEFILTERS, and ALLEXCEPT: Choosing the Right Filter Removal

Filter removal is foundational because many executive questions are comparative: share, rank, variance to benchmark, and contribution. The key is to remove only the filters you intend to remove.

- ALL(Table) removes all filters from that table, including filters coming from related tables via relationships in many scenarios.

- REMOVEFILTERS is similar in intent and often clearer to read; it removes filters from specified columns or tables.

- ALLEXCEPT removes all filters from a table except the columns you specify, useful when you want to keep a grouping level while removing other slicers.

Example: Share of Sales within Region (keep Region, ignore Product)

Assume Region is in a Geography table related to Sales, and Product is in a Product table. If your visual is by Product, you want the denominator to keep the current Region and Date filters but ignore Product:

Sales Share = DIVIDE ( [Total Sales], CALCULATE ( [Total Sales], REMOVEFILTERS ( Product ) ) )DIVIDE is preferred over the / operator because it handles divide-by-zero gracefully.

Iterators (SUMX, AVERAGEX) for Row-Level Business Logic

Many business questions require calculations at the row level before aggregation. For example, margin might be SalesAmount minus CostAmount per line, then summed. If you already have a stored margin column, SUM works. But if margin is derived from multiple columns or requires conditional logic, you often use SUMX.

Example: Total Margin from Line Items

Total Margin = SUMX ( Sales, Sales[SalesAmount] - Sales[CostAmount] )SUMX iterates over the rows of Sales in the current filter context, evaluates the expression per row, and sums the results. This is a direct way to encode “calculate margin per transaction, then total it.”

Example: Weighted Average Selling Price

Executives often ask for average price, but the correct definition is frequently weighted by quantity:

Avg Price (Weighted) = DIVIDE ( [Total Sales], [Total Quantity] )If you need a more complex weighting (for example, excluding free units), you can use an iterator over a summarized table, but start with the simplest correct definition.

Step-by-Step: Translating a Business Question into a DAX Measure

Use a repeatable workflow to avoid “trial-and-error DAX.” The steps below help you build measures that match business intent and remain maintainable.

Step 1: Write the question as a definition

Example question: “What is revenue from returning customers in the last 90 days?” Turn it into a definition: “Sum of SalesAmount for orders in the last 90 days where the customer had at least one purchase before that 90-day window.”

Step 2: Identify the grain and the entities

Grain: sales transactions. Entity: customer. Time window: last 90 days relative to the current date context (or relative to the max visible date).

Step 3: Confirm base measures exist

You need [Total Sales]. You also need a way to identify customers and dates (Customer[CustomerID], Date[Date]).

Step 4: Build helper measures or variables

Variables (VAR) make complex logic readable and faster by reusing intermediate results. You can define the window end date as the maximum visible date, then compute the start date.

Returning Customer Sales (Last 90 Days) = VAR EndDate = MAX ( 'Date'[Date] ) VAR StartDate = EndDate - 90 VAR CustomersWithPriorPurchase = CALCULATETABLE ( VALUES ( Customer[CustomerID] ), 'Date'[Date] < StartDate ) RETURN CALCULATE ( [Total Sales], DATESBETWEEN ( 'Date'[Date], StartDate, EndDate ), KEEPFILTERS ( CustomersWithPriorPurchase ) )This measure demonstrates several foundations: variables, CALCULATETABLE to create a customer set, DATESBETWEEN for the window, and KEEPFILTERS to apply the customer set without wiping out other customer filters. You may need to adjust the “prior purchase” logic depending on your model (for example, ensuring the customer set is derived from Sales rather than Customer alone).

Step 5: Validate with a simple table visual

Before putting the measure on a KPI card, validate it in a table by Customer and Date (or by Month) to ensure it behaves as expected. Check edge cases: customers with first purchase inside the window should not be counted as returning; customers with purchases both before and within the window should be included.

Time Intelligence Foundations: Answering “When” Questions Reliably

Business questions frequently involve comparisons over time: month-to-date, quarter-to-date, year-to-date, last year, rolling 12 months, and period-over-period change. DAX time intelligence becomes reliable when you base it on a proper Date table and write measures that clearly define the comparison period. The key foundation is that time intelligence functions operate over the Date table, not over a date column in the fact table.

Example: Year-to-Date Sales

Sales YTD = TOTALYTD ( [Total Sales], 'Date'[Date] )Example: Sales Same Period Last Year

Sales SPLY = CALCULATE ( [Total Sales], SAMEPERIODLASTYEAR ( 'Date'[Date] ) )Example: YoY Change and YoY %

Sales YoY Change = [Total Sales] - [Sales SPLY]Sales YoY % = DIVIDE ( [Sales YoY Change], [Sales SPLY] )These measures are foundational because they can be reused across any visual. The executive question “Are we up or down versus last year?” becomes a consistent set of measures that work at any time grain (month, quarter, year) as long as the Date table drives the axis.

Ratios and KPIs: Making Measures Executive-Friendly

Executives often want ratios: margin %, conversion rate, on-time delivery rate, churn rate, and utilization. Ratios require careful numerator and denominator definitions under the same filter context. A common mistake is to compute a ratio by averaging row-level ratios, which can distort results. Prefer dividing two additive measures.

Example: Gross Margin and Gross Margin %

Gross Margin = [Total Sales] - [Total Cost]Gross Margin % = DIVIDE ( [Gross Margin], [Total Sales] )Because both numerator and denominator respond to the same filters, the ratio remains consistent when slicing by product, region, or time.

Segmentation Patterns: Top N, Contribution, and Ranking

Segmentation questions include “Who are our top customers?”, “Which products contribute most to revenue?”, and “What is the long tail?” DAX foundations for these questions include RANKX, TOPN, and measures that compute contribution to total.

Example: Rank Products by Sales

Product Sales Rank = RANKX ( ALL ( Product[ProductName] ), [Total Sales], , DESC )ALL removes the product filter so the rank is computed across all products, while still respecting other filters like date and region.

Example: Sales for Top 10 Products

Sales (Top 10 Products) = VAR TopProducts = TOPN ( 10, ALL ( Product[ProductName] ), [Total Sales], DESC ) RETURN CALCULATE ( [Total Sales], KEEPFILTERS ( TopProducts ) )This pattern answers “How much revenue comes from the top 10 products?” and remains interactive with slicers for time and geography.

Handling Blanks, Zeros, and Business-Friendly Output

Executive dashboards must avoid misleading blanks and must handle missing data gracefully. DAX provides tools to control output: COALESCE to replace blanks, IF to apply business rules, and FORMAT for display (use FORMAT sparingly because it converts numbers to text and can break sorting and aggregation).

Example: Show 0 Instead of Blank

Total Sales (No Blank) = COALESCE ( [Total Sales], 0 )Example: Conditional KPI Labeling (numeric output preserved)

Sales YoY Status = VAR Pct = [Sales YoY %] RETURN IF ( ISBLANK ( Pct ), BLANK (), IF ( Pct >= 0, 1, -1 ) )This returns a numeric status you can map to icons or conditional formatting rules without turning the measure into text.

Debugging and Trust: Techniques to Validate DAX Against the Question

DAX foundations include not just writing measures, but proving they answer the question. A practical approach is to create “inspection measures” that reveal intermediate values. Use variables and return intermediate results temporarily to confirm assumptions about context and filters.

Example: Inspect the Current Date Range and Filtered Entities

Debug Max Date = MAX ( 'Date'[Date] )Debug Customer Count = DISTINCTCOUNT ( Customer[CustomerID] )Place these in a card visual while testing slicers. If a measure is wrong, the issue is often that the filter context is different than you expect. Debug measures help you see what the report is actually filtering.

Common Business-Question Templates and the DAX Pattern Behind Them

Many executive questions fall into templates. Recognizing the template helps you choose the right DAX pattern quickly.

- “Total for a subset” (e.g., completed orders, premium customers): use CALCULATE with a filter condition.

- “Share of total” (e.g., product share within region): use DIVIDE with a denominator that removes only the relevant filters.

- “Change over time” (e.g., YoY, MoM): compute current period, comparison period, then difference and percent.

- “Rolling window” (e.g., last 30/90/365 days): define StartDate and EndDate with variables, then apply DATESBETWEEN.

- “Top N / ranking” (e.g., top customers): use RANKX or TOPN with ALL on the ranked dimension.

- “Threshold-based counts” (e.g., customers with sales > 10k): build a summarized table and count rows meeting the condition.

Example: Count of Customers Above a Revenue Threshold

Question: “How many customers generated at least 10,000 in sales in the selected period?”

Customers >= 10k = VAR CustomerSales = SUMMARIZE ( Customer, Customer[CustomerID], "SalesAmt", [Total Sales] ) RETURN COUNTROWS ( FILTER ( CustomerSales, [SalesAmt] >= 10000 ) )This pattern uses SUMMARIZE to create a per-customer table in the current filter context, then FILTER and COUNTROWS to answer the threshold question. It is a common executive request for segmentation and pipeline-style reporting.