Why the finish date is not driven by “a lot of work,” but by a specific chain

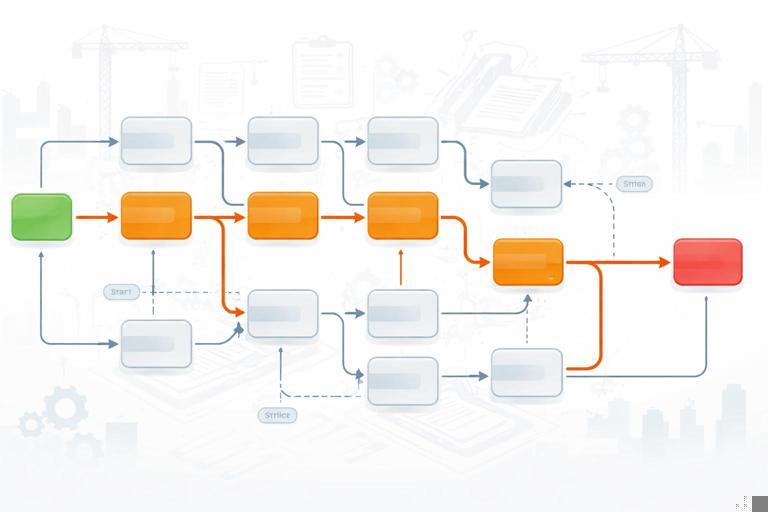

On a real project, dozens (or hundreds) of activities happen in parallel. Some are truly time-critical; others have flexibility. The finish date is driven by the longest continuous chain of dependent activities from the start of the schedule to the end. That chain is the critical path. If you shorten an activity that is not on that chain, you may improve utilization or reduce risk, but you may not move the project finish date at all.

To manage time intentionally, you need three things working together: (1) identify the critical path, (2) understand float (how much flexibility each activity has), and (3) recognize that the “driver” of the finish date can change as the job progresses. The goal is not to memorize definitions; it is to know where to focus daily attention and what to protect.

Critical path in practical terms

The critical path is the sequence of activities that determines the earliest possible project completion date given the current logic and durations. Activities on the critical path have zero total float (or near-zero, depending on software settings and calendars). If any critical activity slips by one day and nothing else changes, the project finish slips by one day.

Two important clarifications for construction schedules:

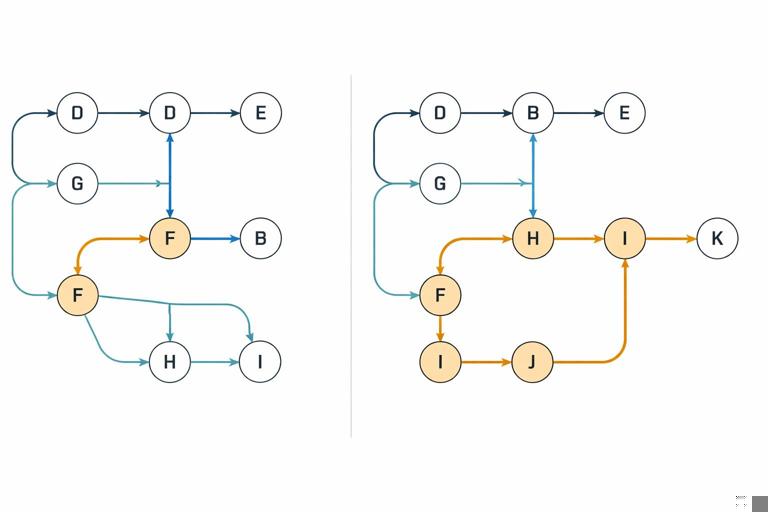

- There can be more than one critical path. If two different chains tie for the longest duration, both are critical. This is common when you have parallel workstreams (e.g., base building and tenant improvements) that both must finish before turnover.

- Critical is a property of the network, not the activity type. “Inspections” or “submittals” are not automatically critical; they become critical when their position in the logic makes them part of the longest chain.

Early dates, late dates, and the idea of “driving”

Critical path is computed using two passes through the network:

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

- Forward pass calculates the earliest start (ES) and earliest finish (EF) for each activity based on predecessors.

- Backward pass calculates the latest finish (LF) and latest start (LS) that still allow the project to finish on the calculated completion date.

An activity is “driving” another when its finish (or start) actually controls the successor’s earliest possible start (or finish) under the logic type. In many schedules, multiple predecessors feed a successor; only the one that finishes last is the driving predecessor at that moment.

Float: the flexibility you can spend (or waste)

Float is the amount of time an activity can slip without causing a delay to something else. Float is not “extra time the project manager added.” It is a calculated result of the network logic and durations.

Total float vs. free float

- Total float (TF): how much an activity can slip without delaying the project finish date (or the end of its controlling path). This is the most commonly used float in CPM management.

- Free float (FF): how much an activity can slip without delaying the early start of its immediate successor(s). Free float is usually less than or equal to total float.

In field management, total float answers: “Can I move this activity later and still hit the overall completion?” Free float answers: “If I move this activity later, will I immediately push the next crew?”

Float is not a permission slip

A common failure mode is treating float as “available days to burn.” Float is better treated as a buffer to protect because it absorbs uncertainty: weather, late deliveries, rework, inspections, and crew availability. When you consume float early, you reduce your ability to handle surprises later. Good teams spend float intentionally, not casually.

Negative float and what it really means

Negative float appears when a required date (often a contractual milestone, owner move-in, or constraint) is earlier than what the current network can achieve. It is the schedule’s way of saying: “With these durations and logic, you cannot meet the required date.”

Negative float is not solved by hiding it. It is solved by changing reality in the model: resequencing, adding resources, changing means and methods, splitting work, overlapping phases, or negotiating the required date.

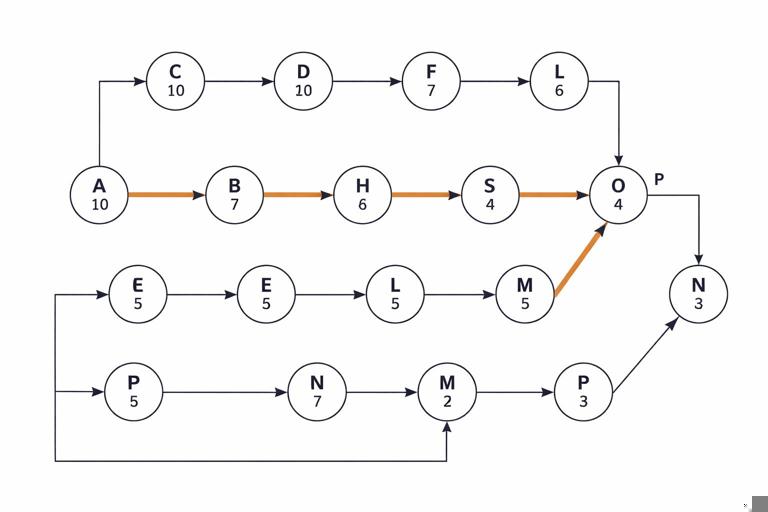

A worked example: find the critical path and float by hand

The most reliable way to understand critical path is to compute it on a small network. Below is a simplified example with finish-to-start relationships and a single project finish milestone. Durations are in workdays.

Activities (Duration) and Logic (FS unless noted) A: Mobilize (2) B: Layout (1) after A C: Excavate (4) after B D: Form footings (3) after C E: Rebar footings (2) after D F: Pour footings (1) after E G: Cure footings (2) after F H: Frame (6) after G I: Rough MEP (5) after H J: Insulate (2) after I K: Drywall (4) after J L: Paint (3) after K M: Flooring (3) after L N: Final inspection (1) after M O: Owner move-in milestone (0) after N Parallel branch: P: Order windows (0) after A Q: Fabricate windows (10) after P R: Deliver windows (1) after Q S: Install windows (2) after H and RStep 1: Forward pass (earliest dates)

Start at day 0. Compute ES/EF by adding durations along each path.

- A ES 0 EF 2

- B ES 2 EF 3

- C ES 3 EF 7

- D ES 7 EF 10

- E ES 10 EF 12

- F ES 12 EF 13

- G ES 13 EF 15

- H ES 15 EF 21

- I ES 21 EF 26

- J ES 26 EF 28

- K ES 28 EF 32

- L ES 32 EF 35

- M ES 35 EF 38

- N ES 38 EF 39

- O milestone ES 39 EF 39

Now the window branch:

- P ES 2 EF 2 (0-day activity after A)

- Q ES 2 EF 12

- R ES 12 EF 13

- S depends on H (EF 21) and R (EF 13), so ES is the later of the two: ES 21 EF 23

Notice something important: even though windows take 10 days to fabricate, they are ready by day 13, long before framing finishes at day 21. In this model, windows are not driving the start of installation; framing is driving.

Step 2: Backward pass (latest dates)

Set the project finish milestone O at LF 39. Then move backward.

- N must finish by 39, so N LF 39 LS 38

- M LF 38 LS 35

- L LF 35 LS 32

- K LF 32 LS 28

- J LF 28 LS 26

- I LF 26 LS 21

- H LF 21 LS 15

- G LF 15 LS 13

- F LF 13 LS 12

- E LF 12 LS 10

- D LF 10 LS 7

- C LF 7 LS 3

- B LF 3 LS 2

- A LF 2 LS 0

For S (install windows), it is not tied to the finish milestone in this simplified network unless you connect it to a downstream activity. In a real schedule, window installation would typically be a predecessor to weather-tightness, rough-in, or inspections. To keep the example meaningful, assume S must be complete before Rough MEP (I) can start (common if you require building dried-in). Add logic: I after S. Now recompute the relevant portion:

With I after S, I ES becomes max(H EF 21, S EF 23) = 23, pushing the whole interior chain by 2 days. The project finish becomes day 41. That means the window chain becomes critical because it now drives I.

This illustrates a key jobsite lesson: the critical path is sensitive to the logic you choose. If “dried-in” is truly required before rough MEP, the schedule must reflect it; otherwise, you will underestimate the finish date and misallocate attention.

Step 3: Calculate total float

Total float is commonly computed as TF = LS − ES (equivalently LF − EF).

In the first version (without I after S), the main chain A→…→O has TF = 0 throughout, so it is the critical path. The window fabrication activities Q and R have significant float because they finish early and do not drive anything.

In the second version (with I after S), the controlling chain becomes A→P→Q→R→S→I→…→O (and also includes H because S depends on H). Many activities that previously had float may now have zero float. This is exactly what happens on projects when you add a missing relationship or when a late procurement item suddenly becomes the driver.

What really drives the finish date (and why it changes)

1) The longest path, not the busiest area

The finish date is driven by the longest chain of dependencies. The busiest area of the site may be irrelevant if it has float. For example, landscaping can be visually prominent near the end of a project, but if it has 15 days of float and the critical path runs through commissioning and inspections, the finish date is not driven by landscaping.

2) The current driving predecessor at merge points

Whenever multiple predecessors feed one successor, the predecessor that finishes last is the driver. This can change week to week. A practical way to manage this is to identify merge points such as:

- “Start drywall” (requires rough MEP complete, inspections passed, materials on site)

- “Start ceiling grid” (requires above-ceiling inspections, ductwork complete, lighting rough-in complete)

- “Start commissioning” (requires equipment startup, controls integration, TAB readiness)

At each merge point, ask: “Which predecessor is currently forecast to be last?” That is where you focus expediting and problem-solving.

3) Calendars, access windows, and non-working time

Critical path is calculated in working time. If one trade works Saturdays and another does not, the same “5-day duration” can land on different calendar dates. Also, access restrictions (night work, shutdown windows, owner occupancy constraints) can create hidden drivers. A path that looks shorter in workdays can become the driver in calendar days if it crosses more non-working time or restricted periods.

4) Long-lead procurement and approvals when they are truly linked

Procurement only drives the finish date when it is logically tied to installation and downstream work. The schedule must connect: approval → fabrication → delivery → install → downstream activities. If procurement is modeled as a standalone list with no successors, it will never appear critical even if it is the real-world driver.

5) Rework loops and quality gates

Inspections, testing, punchlists, and authority approvals can become critical when they are modeled as single activities with optimistic durations and no allowance for rework. In practice, the driver is often not the inspection itself but the cycle time: prepare → inspect → correct → re-inspect. If you do not model the loop, you may miss the true driver of the finish date.

Step-by-step: how to use critical path and float in weekly control

Step 1: Identify the current critical path and near-critical paths

In your scheduling tool, filter or highlight activities with total float ≤ a threshold (often 0–5 days). Near-critical paths are dangerous because small issues can make them critical. Treat “near-critical” as “needs management,” not as “safe.”

Step 2: Verify the logic at the next 4–8 week horizon

Critical path is only as good as the logic. For the lookahead window, verify that key handoffs are correctly linked. Typical checks:

- Does “start drywall” truly wait for “rough inspection passed,” or only for “rough complete”?

- Does “set RTU” link to “curb installed” and “crane scheduled,” or is it floating?

- Are temporary works (shoring removal, temp power, temp heat) linked to the activities that depend on them?

The objective is not to add thousands of links; it is to ensure the next set of commitments reflects real constraints.

Step 3: Use float to prioritize expediting and crew moves

When resources are limited, prioritize by impact:

- Critical activities (TF ≈ 0): protect them first. Ensure materials, access, and inspections are lined up.

- Near-critical activities (TF small): remove foreseeable blockers early (submittal status, lead times, coordination issues).

- High-float activities: you can shift them to solve a constraint elsewhere, but track float consumption so you do not create a new critical path unintentionally.

A practical rule: if you “borrow” float from an activity to solve a problem, record how much you borrowed and what you gained. This makes float a managed resource rather than an invisible one.

Step 4: Watch for critical path migration

Critical path migration happens when progress differs from plan. Examples:

- A critical concrete sequence recovers time, but a delayed equipment delivery becomes the new driver.

- Interior finishes accelerate, but commissioning and owner training become the longest chain.

- Weather delays push exterior enclosure later, making dried-in the driver for multiple interior trades.

To detect migration, compare last update’s critical path to this update’s. If the driver changed, adjust your weekly focus and communicate the change clearly to the team.

Step 5: Manage constraints that create “false criticality”

Sometimes an activity shows as critical because of a constraint date or a hard-coded milestone, not because it is truly the longest chain. Examples include “Must Start On” constraints or unrealistic imposed dates. These can mask the real driver by forcing dates rather than letting the network calculate them. In control meetings, distinguish:

- Network-driven criticality: the logic and durations create the finish date.

- Constraint-driven criticality: a fixed date forces the schedule, often producing negative float elsewhere.

Constraint-driven criticality is not automatically wrong—projects do have immovable dates—but it requires a plan to make the network achievable (resequencing, added shifts, scope tradeoffs, etc.).

Common field scenarios and how critical path/float clarifies decisions

Scenario A: “We need to start drywall Monday”

Drywall start is often a merge point. If rough MEP is 2 days late but has 3 days of float, and the above-ceiling inspection is 1 day late with 0 float, the inspection is the driver. The correct action is to expedite inspection readiness (labels, access, test results) rather than pushing crews harder on rough-in that is not currently driving.

Scenario B: “Add a second crew to flooring”

If flooring has 10 days of total float, adding a second crew may not move the finish date. It might still be worth it for other reasons (quality, risk, owner preference), but it is not a schedule recovery action. If commissioning has 0 float and is forecast late, resources should shift toward prerequisites for commissioning (startup, controls integration, TAB, punch closure) instead.

Scenario C: “The elevator is late”

An elevator can be either critical or irrelevant depending on turnover requirements. If the certificate of occupancy requires elevator operation, the elevator chain is likely critical. If the building can be occupied without it (temporary stairs allowed, partial occupancy), it may have float. The schedule must reflect the actual occupancy and inspection requirements; then float will tell you whether expediting the elevator affects the finish date.

Practical tips to keep critical path and float meaningful

- Avoid open ends. Activities without successors can hide critical work. Ensure every activity (especially procurement, inspections, and testing) ties into downstream deliverables.

- Use realistic activity splitting. If “MEP rough-in” is a single 20-day activity, it is hard to see what is driving. Splitting by area or system can reveal the true driver and create actionable float information.

- Be careful with excessive constraints. Over-constraining can produce misleading float and prevent the schedule from recalculating logically after updates.

- Track float trends, not just float values. An activity with 8 days float that had 20 days last month is a warning sign even if it is not yet near-critical.

- Validate with the field. If the schedule says a path is critical but the superintendent knows another item is gating access or inspections, the logic is missing something. Fix the model so the critical path matches reality.