Why configuration and secrets become hard in real environments

In development, it is common to keep configuration in a local file and share a few environment variables. In real environments (staging, production, multiple regions, multiple clusters), configuration becomes a moving target: values differ per environment, per tenant, and sometimes per deployment wave. At the same time, secrets must be protected, rotated, audited, and delivered to workloads without leaking into logs, Git history, or container images.

A practical approach is to treat configuration and secrets as first-class deployment artifacts with clear ownership, lifecycle, and delivery mechanisms. The goal is to make changes safe and repeatable: you should be able to answer “what config is running?”, “who changed it?”, “how do we roll it back?”, and “how do we rotate credentials without downtime?”

Configuration vs secrets (and why the boundary matters)

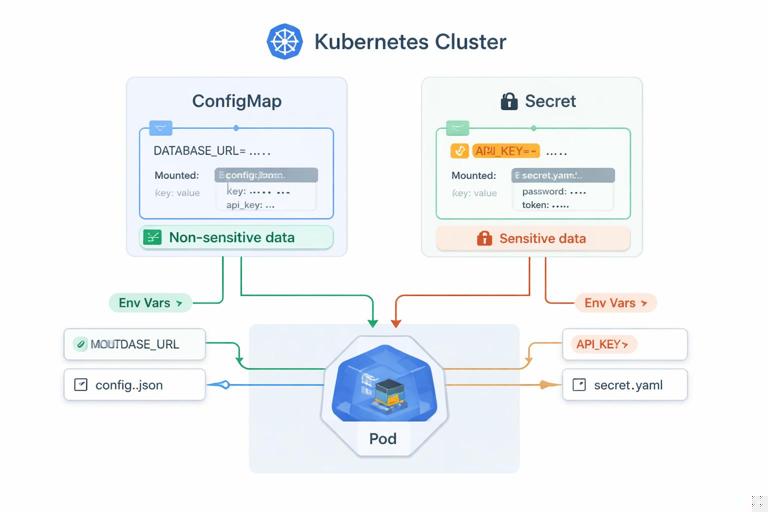

Configuration is any value that changes behavior without changing code: feature flags, URLs, timeouts, log levels, concurrency, cache sizes, and environment-specific toggles. Secrets are values that grant access or prove identity: passwords, API keys, tokens, private keys, database credentials, and encryption keys.

The boundary matters because secrets require stronger controls: encryption at rest, restricted RBAC, limited distribution, rotation, and careful handling in CI/CD. Configuration can often be stored in Git and reviewed like code; secrets usually should not be stored in Git in plaintext.

Kubernetes primitives for configuration delivery

ConfigMaps for non-sensitive configuration

A ConfigMap stores key/value pairs or entire files. It is designed for non-sensitive data. You can consume it as environment variables or mount it as files. File mounts are often preferable for larger structured config (YAML/JSON) and for applications that can reload config from disk.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: app-config

data:

LOG_LEVEL: "info"

FEATURE_X_ENABLED: "false"

app.yaml: |

server:

readTimeout: 5s

writeTimeout: 10s

limits:

maxItems: 1000Consume as environment variables:

envFrom:

- configMapRef:

name: app-configConsume as files:

volumeMounts:

- name: config

mountPath: /etc/app

volumes:

- name: config

configMap:

name: app-config

items:

- key: app.yaml

path: app.yamlSecrets for sensitive values

Kubernetes Secrets are base64-encoded objects intended for sensitive data. Base64 is not encryption; the security comes from access controls, optional encryption at rest in the cluster, and careful operational practices. Like ConfigMaps, Secrets can be injected as environment variables or mounted as files.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: db-credentials

type: Opaque

data:

username: YXBw

password: c3VwZXJzZWNyZXQ=Mount as files (often safer than env vars because env vars can leak via process listings, crash dumps, or debug endpoints):

volumeMounts:

- name: db-creds

mountPath: /var/run/secrets/db

readOnly: true

volumes:

- name: db-creds

secret:

secretName: db-credentialsThen your app reads /var/run/secrets/db/username and /var/run/secrets/db/password.

Real-environment patterns: layering, ownership, and drift control

Layer configuration by scope

Most teams benefit from a layered model:

- Base (global): defaults that apply everywhere (timeouts, common labels, standard ports, default feature flags).

- Environment: staging vs production differences (replica counts, log level, external endpoints, rate limits).

- Region/cluster: region-specific endpoints, failover priorities, data residency toggles.

- Tenant/customer (if applicable): per-tenant limits, feature entitlements.

Layering prevents copy/paste sprawl and makes it clear where a value should live. It also reduces the blast radius of changes: a tenant override should not require editing global defaults.

Keep configuration declarative and reviewable

For non-secret configuration, store it in Git and deploy it declaratively. This enables code review, change history, and easy rollbacks. Avoid “kubectl edit” in production for anything that should be reproducible.

Prevent configuration drift

Drift happens when the running cluster differs from the intended state. Even if you use GitOps, drift can occur through manual changes, controllers mutating resources, or emergency patches. Practical drift control includes:

- Restricting write access to production namespaces via RBAC.

- Using admission policies to block risky patterns (for example, disallowing plaintext secrets in ConfigMaps).

- Monitoring for changes to ConfigMaps/Secrets and alerting on unexpected updates.

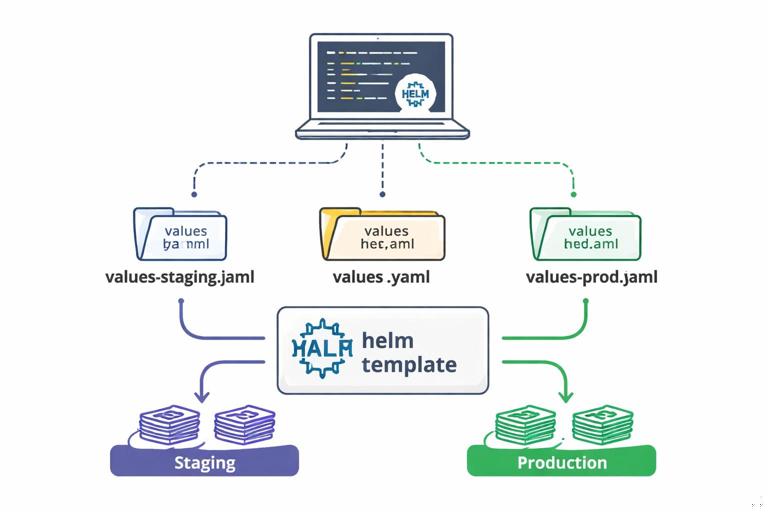

Step-by-step: environment-specific configuration with Helm values

Helm is commonly used to template Kubernetes manifests and manage environment-specific values. A practical pattern is to keep a chart with sane defaults and provide separate values files per environment.

1) Define values in values.yaml

# values.yaml

config:

logLevel: info

featureX: false

resources:

requests:

cpu: 100m

memory: 128Mi

limits:

cpu: 500m

memory: 512Mi2) Create environment overrides

# values-staging.yaml

config:

logLevel: debug

featureX: true# values-prod.yaml

config:

logLevel: warn

featureX: false

resources:

requests:

cpu: 300m

memory: 256Mi3) Template a ConfigMap from values

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: {{ include "myapp.fullname" . }}-config

data:

LOG_LEVEL: {{ .Values.config.logLevel | quote }}

FEATURE_X_ENABLED: {{ .Values.config.featureX | quote }}4) Deploy with the right values file

helm upgrade --install myapp ./chart -f values-staging.yaml -n staginghelm upgrade --install myapp ./chart -f values-prod.yaml -n prodThis keeps environment differences explicit and reviewable. For larger configs, template a file into the ConfigMap and mount it into the container.

Step-by-step: safe secret delivery without committing secrets to Git

In real environments, you typically want Git to contain references to secrets, not the secret material. Two common approaches are: (1) External secret stores synced into Kubernetes, or (2) Sealed/encrypted secrets stored in Git. The right choice depends on your compliance requirements and operational maturity.

Approach A: External Secrets Operator (sync from a secret manager)

This approach stores the source of truth in a dedicated secrets manager (for example, AWS Secrets Manager, Azure Key Vault, or HashiCorp Vault). Kubernetes receives a generated Secret, and workloads consume it normally.

1) Create a SecretStore (example structure)

apiVersion: external-secrets.io/v1beta1

kind: SecretStore

metadata:

name: cloud-secrets

spec:

provider:

aws:

service: SecretsManager

region: us-east-1

auth:

jwt:

serviceAccountRef:

name: external-secrets-sa2) Define an ExternalSecret mapping

apiVersion: external-secrets.io/v1beta1

kind: ExternalSecret

metadata:

name: db-credentials

spec:

refreshInterval: 1h

secretStoreRef:

name: cloud-secrets

kind: SecretStore

target:

name: db-credentials

creationPolicy: Owner

data:

- secretKey: username

remoteRef:

key: prod/myapp/db

property: username

- secretKey: password

remoteRef:

key: prod/myapp/db

property: password3) Consume the resulting Kubernetes Secret

Your Deployment mounts db-credentials like any other Secret. Rotation becomes a matter of updating the secret in the external manager; the operator refreshes it on schedule.

Operational notes:

- Use dedicated service accounts and least-privilege IAM policies so the operator can only read the secrets it needs.

- Set refresh intervals based on rotation requirements and API rate limits.

- Plan how your app reacts to secret updates: some apps need a restart to pick up new values.

Approach B: Sealed Secrets (encrypted secrets in Git)

Sealed Secrets encrypt secret data with a cluster public key. You commit the encrypted “SealedSecret” to Git; only the controller in the cluster can decrypt it into a normal Secret.

This is useful when you want GitOps-style workflows without running an external secret manager, but it introduces cluster-coupling: the sealed secret is typically bound to a specific cluster key (unless you manage key sharing carefully).

Operational notes:

- Back up the controller keys; losing them can make recovery difficult.

- Define a rotation process for the sealing keys and for the underlying credentials.

- Limit who can create SealedSecrets, because that effectively grants the ability to create Secrets in the cluster.

Secret consumption patterns: env vars vs files vs CSI

Environment variables

Pros: easy for twelve-factor style apps; no file parsing needed. Cons: can leak through debugging, process inspection, or accidental logging; updates usually require a restart.

Mounted files

Pros: avoids some env var leakage; supports structured secrets (cert bundles, JSON credentials). Cons: apps must read files; some frameworks read env vars more naturally.

Secrets Store CSI Driver (mount directly from external store)

With CSI, secrets can be mounted into pods directly from an external provider without creating a Kubernetes Secret (optional sync exists). This can reduce secret sprawl inside the cluster and can support short-lived credentials. It also adds a dependency on the CSI driver and provider configuration.

Operational notes:

- Prefer short-lived credentials when possible (dynamic DB users, cloud IAM tokens).

- Ensure node and pod identity is configured correctly (workload identity, IRSA, etc.).

- Test failure modes: what happens if the external secret store is temporarily unavailable?

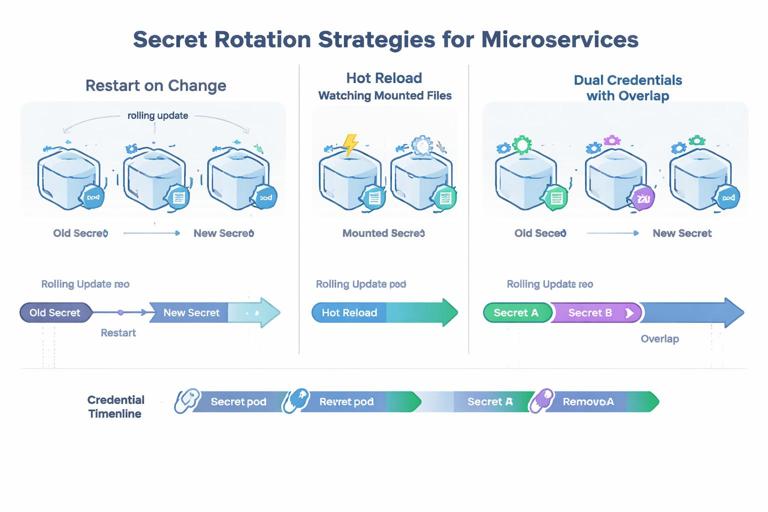

Rotation and reload: designing for change without downtime

Real environments require rotation: database passwords expire, API keys are compromised, and certificates renew. Rotation is not just “update the secret”; it is also “ensure the application picks it up safely.”

Common rotation strategies

- Restart on change: simplest. When the Secret changes, trigger a rollout restart. This works well if your app starts quickly and is stateless.

- Hot reload: the app watches files and reloads credentials without restarting. This is ideal for long-lived connections but requires careful coding and testing.

- Dual credentials: rotate by introducing a new credential while the old remains valid, then switch consumers, then revoke the old. This reduces downtime risk.

Triggering rollouts when ConfigMaps/Secrets change

Kubernetes does not automatically restart pods when a ConfigMap/Secret changes if you consume it via environment variables. Even with file mounts, updates may not be picked up by the application. A common pattern is to add an annotation to the Pod template that changes when the config changes, forcing a rollout.

In Helm, you can compute a checksum of the rendered ConfigMap/Secret and place it in the Deployment template metadata.

metadata:

annotations:

checksum/config: {{ include (print $.Template.BasePath "/configmap.yaml") . | sha256sum }}

checksum/secret: {{ include (print $.Template.BasePath "/secret.yaml") . | sha256sum }}When the ConfigMap or Secret content changes, the checksum changes, Kubernetes treats it as a new ReplicaSet, and performs a rolling update.

Hardening: RBAC, encryption at rest, and namespace boundaries

RBAC: least privilege for reading secrets

By default, any subject with permission to read Secrets in a namespace can exfiltrate credentials. In production, treat “get/list/watch secrets” as highly privileged.

- Grant applications access only to the specific secrets they need (often via mounting, not API reads).

- Avoid giving developers broad secret read access in production namespaces.

- Separate duties: CI/CD may apply manifests but should not necessarily be able to read back secret values.

Encrypt secrets at rest in the cluster

Enable encryption at rest for Kubernetes Secrets in etcd using an encryption provider configuration. This protects against disk theft or etcd snapshot exposure. It does not replace RBAC; it complements it.

Operational notes:

- Manage encryption keys securely (KMS integration if available).

- Plan key rotation and test recovery procedures.

- Ensure backups are encrypted and access-controlled.

Namespace and cluster segmentation

Use namespaces to separate environments and limit blast radius. For higher assurance, separate production into its own cluster. This reduces the chance that a staging compromise leads to production secret exposure.

Preventing accidental leakage in pipelines and runtime

CI/CD hygiene

- Do not print secrets in build logs. Mask sensitive variables and avoid verbose debug output.

- Use short-lived credentials for CI jobs (OIDC-based cloud auth, Vault dynamic tokens).

- Scan repositories for committed secrets and enforce pre-receive hooks or CI checks.

Application logging and error handling

Many leaks happen when applications log full configuration objects or include headers/tokens in error messages. Practical safeguards:

- Redact known sensitive keys (password, token, authorization, apiKey) in log middleware.

- Do not log full environment dumps on startup in production.

- Ensure panic/crash handlers do not include secret-bearing structures.

Kubernetes events and debugging tools

Be careful with tools that describe pods or dump environment variables. Limit who can run interactive debugging in production namespaces. Prefer controlled break-glass procedures with auditing.

Managing complex configuration: schemas, validation, and safe defaults

Use a schema and validate at startup

As configuration grows, failures shift from “missing env var” to subtle misconfiguration (wrong units, invalid URLs, contradictory flags). Use a schema (JSON Schema, typed config structs, or validation libraries) and fail fast with clear errors that do not print secrets.

Practical checklist:

- Validate required fields and ranges (timeouts, ports, concurrency).

- Validate cross-field constraints (if feature enabled, endpoint must be set).

- Provide safe defaults for optional values.

Separate “tuning knobs” from “identity and access”

Keep performance tuning (thread counts, cache sizes) in ConfigMaps and keep identity/access material in Secrets or external stores. This separation reduces the temptation to put everything into one blob and makes RBAC easier.

Step-by-step: putting it together for a production-ready workload

1) Create a ConfigMap for non-sensitive settings

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: myapp-config

data:

LOG_LEVEL: "warn"

REQUEST_TIMEOUT: "3s"

FEATURE_FLAGS: "payments_v2=false,search_v3=true"2) Provision secrets via an external store sync (or another approved method)

apiVersion: external-secrets.io/v1beta1

kind: ExternalSecret

metadata:

name: myapp-secrets

spec:

refreshInterval: 30m

secretStoreRef:

name: cloud-secrets

kind: SecretStore

target:

name: myapp-secrets

data:

- secretKey: DATABASE_URL

remoteRef:

key: prod/myapp/database

property: url

- secretKey: API_TOKEN

remoteRef:

key: prod/myapp/integrations

property: token3) Mount config and secrets with least exposure

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: myapp

spec:

template:

metadata:

annotations:

checksum/config: "replace-with-helm-checksum"

checksum/secret: "replace-with-helm-checksum"

spec:

containers:

- name: myapp

image: myorg/myapp:1.2.3

envFrom:

- configMapRef:

name: myapp-config

volumeMounts:

- name: secrets

mountPath: /var/run/secrets/myapp

readOnly: true

volumes:

- name: secrets

secret:

secretName: myapp-secretsIn the application, read sensitive values from files (for example, /var/run/secrets/myapp/API_TOKEN) and non-sensitive values from environment variables. This keeps the most sensitive data out of env var dumps and makes it easier to rotate.

4) Plan rotation and response

- Define how often each credential rotates and who owns it.

- Decide whether the app supports hot reload; if not, implement a controlled restart on secret change.

- Test rotation in staging: rotate the secret and verify the app continues to serve traffic and reconnects successfully.

Operational guardrails for teams

Define ownership and change workflows

Configuration changes should have an owner and a workflow. For example:

- Application team owns ConfigMap keys and their semantics.

- Platform/security team owns secret store policies, encryption, and access boundaries.

- On-call runbooks specify how to rotate a credential and how to roll back a bad config.

Auditability and traceability

Ensure you can trace changes to configuration and secrets:

- Use Git history and pull requests for ConfigMaps and Helm values.

- Use secret manager audit logs for reads and updates.

- Enable Kubernetes audit logs for access to Secret resources where required.