What “Closing” Really Means in Non‑Sales Negotiations

In non‑sales roles, “closing” is rarely a dramatic moment where someone says yes and signs on the spot. More often, closing is the disciplined process of converting a tentative alignment (“Sounds good”) into a shared, unambiguous commitment that survives handoffs, time pressure, and organizational complexity.

A close is successful when: (1) both sides can restate the agreement the same way, (2) the agreement is actionable (who does what by when), and (3) the agreement is resilient—meaning it anticipates predictable misunderstandings and prevents them from turning into rework or conflict.

Misunderstandings at the close usually come from one of four gaps:

- Language gap: vague terms like “ASAP,” “best effort,” “reasonable,” “support,” or “done.”

- Scope gap: different assumptions about what is included/excluded.

- Authority gap: the person agreeing cannot actually commit resources or approvals.

- Memory gap: people remember different versions after the meeting, especially when multiple topics were discussed.

Closing is the set of techniques that closes these gaps before they become problems.

Common Failure Modes at the Finish Line

1) “We agreed… but we meant something else”

This happens when the agreement is expressed in broad outcomes but not translated into deliverables and acceptance criteria. Example: “Your team will provide analytics support.” One side imagines a dedicated analyst; the other imagines a monthly dashboard template.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

2) “We agreed… but it’s not approved”

Teams often negotiate with someone who is influential but not the final approver (procurement, legal, finance, security, leadership). If approvals are not explicitly built into the close, the agreement can unravel later.

3) “We agreed… but priorities changed”

When timelines are not tied to dependencies and escalation paths, shifting priorities can quietly stall execution. A close should include what happens if a deadline slips or a dependency fails.

4) “We agreed… but it wasn’t written down”

Verbal alignment is fragile. Even with high trust, people forget details or interpret them through their own constraints. A written recap is not bureaucracy; it is insurance.

A Practical Closing Process (Step‑by‑Step)

The following steps work for internal agreements (cross‑functional commitments, resourcing, scope) and external agreements (vendors, partners, service terms). Adapt the formality to the risk level, but keep the structure.

Step 1: Signal the transition from exploring to committing

Many misunderstandings start because the conversation never clearly shifts into “decision mode.” Use a simple verbal marker that you are moving to closure.

- Phrase options: “Let’s summarize what we’re agreeing to so we can execute cleanly.” “I want to make sure we’re aligned on the final terms and next steps.”

- Why it works: It invites correction without sounding adversarial and prepares everyone to listen for specifics.

Step 2: Restate the agreement in a structured summary

Use a consistent template so nothing important is missed. Keep it short, but specific.

- Deliverables: What will be produced or provided?

- Scope boundaries: What is explicitly included and excluded?

- Timeline: Key dates, milestones, and review points.

- Owners: One accountable owner per deliverable.

- Dependencies: What must happen first, and who controls it?

- Quality/acceptance: How will “done” be verified?

- Resources/costs: Budget, headcount, tools, or access required.

- Risks and mitigations: Known risks and what you’ll do if they occur.

Example (internal): “To confirm: your team will provide one data extract per week (CSV, fields A–F) starting Feb 1. We’ll own the transformation and dashboard build. If the schema changes, you’ll notify us 5 business days in advance. We’ll review the first two extracts together to confirm accuracy. Owner on your side: Priya; on ours: Mateo.”

Step 3: Convert vague terms into operational definitions

Listen for words that invite interpretation. Replace them with measurable or observable definitions.

- “ASAP” → “by end of day Thursday” or “within 2 business days.”

- “Support” → “attend weekly 30‑minute sync, respond to questions within 24 hours, and provide up to 6 hours/week of analyst time.”

- “Priority” → “ranked #2 for the team this sprint; if an incident occurs, this may slip by up to 3 days.”

- “Best effort” → “we will attempt X; if not feasible by date Y, we will escalate to Z for a decision.”

A useful prompt: “When we say ‘done,’ what would we see that proves it’s done?”

Step 4: Confirm authority and approval path

Prevent the “I need to run this by…” surprise by explicitly mapping approvals into the close.

- Ask: “Who else needs to approve this for it to be real?”

- Clarify: “Is this within your signing/decision authority?”

- Document: “Pending legal review by Friday; procurement to issue PO next week.”

If approvals are uncertain, close on a conditional agreement with a clear next step: “We’re aligned on the commercial terms, contingent on security review. If security requests changes, we’ll reconvene within 48 hours to adjust.”

Step 5: Lock the trade‑offs and prevent “term drift”

Misunderstandings often appear when one side later tries to adjust a single term without revisiting the balance of the whole deal. Prevent this by explicitly linking the terms.

Example: “We can commit to the two‑week timeline because you’re providing the test environment by Monday and limiting scope to the three core workflows. If either changes, we’ll revisit the timeline.”

This is not a threat; it is a reality statement that protects both sides from hidden costs.

Step 6: Define change control (how new requests will be handled)

Even small agreements benefit from a lightweight change process. Without it, misunderstandings show up as “quick asks” that accumulate.

- Trigger: What counts as a change? (new deliverable, new stakeholder requirement, timeline shift, additional review cycles)

- Process: Who evaluates impact and who approves?

- Options: “Add time,” “add resources,” “remove scope,” or “defer to later.”

Example language: “If new requirements emerge after sign‑off, we’ll document them in a change request, estimate impact within 2 business days, and agree whether to extend the deadline or swap out lower‑priority items.”

Step 7: Establish communication cadence and escalation

Many misunderstandings are not about the deal terms but about silence: people assume progress, while the other side is blocked. Close with a simple operating rhythm.

- Cadence: weekly check‑in, async updates, or milestone reviews.

- Single points of contact: one primary and one backup per side.

- Escalation: “If blocked more than 48 hours, escalate to X and Y.”

Example: “We’ll do a 20‑minute check‑in every Tuesday. If we miss a milestone, we’ll flag it same day and propose a recovery plan within 24 hours.”

Step 8: Write the recap immediately (and invite corrections)

The fastest way to prevent misunderstandings is a written summary sent while the conversation is fresh. The recap should be neutral, structured, and easy to confirm.

Send it within a few hours when possible. Use a subject line that makes it easy to find later (e.g., “Agreement summary + next steps — Project X”).

Include a correction prompt: “Reply with any edits by tomorrow 3pm; otherwise we’ll proceed based on this summary.” This is not a legal trick; it is a coordination mechanism.

Templates You Can Reuse

1) Meeting recap template (internal or external)

Subject: Agreement summary + next steps — [Topic/Project] (Date) Hi [Name/team], Thanks for today. Here’s my understanding of what we agreed: 1) Objective/outcome: - [One sentence] 2) Deliverables (what “done” looks like): - [Deliverable 1 + acceptance criteria] - [Deliverable 2 + acceptance criteria] 3) Scope boundaries: - Included: [items] - Excluded: [items] 4) Timeline & milestones: - [Milestone + date] - [Milestone + date] 5) Owners & responsibilities: - [Name] owns [X] - [Name] owns [Y] 6) Dependencies/inputs needed: - From [team]: [input] by [date] 7) Approvals/conditions: - [Legal/procurement/security/leadership] review by [date] 8) Change control: - Any new requirements will be documented; impact assessed within [time]; we’ll agree on [add time/add resources/remove scope]. 9) Communication & escalation: - Cadence: [weekly/biweekly] - Escalation if blocked > [time]: [person/role] Please reply with any corrections by [deadline]. If I don’t hear back, we’ll proceed on this basis. Best, [You]2) “Definition of done” checklist (quick version)

- What artifact exists at the end? (document, dataset, feature, report, training)

- Who reviews/approves it?

- What objective criteria must be met? (accuracy %, performance, formatting, compliance)

- What is explicitly not included?

- Where will it live and who maintains it?

3) Conditional close language (when approvals are pending)

Use conditional closes when you have alignment but not final authority. Keep them explicit and time‑bound.

- “We’re aligned on X and Y, contingent on Z approval by Friday. If Z requests changes, we’ll meet Monday to adjust.”

- “Assuming security signs off on the data flow, we’ll start implementation on the 15th. If security blocks it, we’ll switch to the alternative approach we discussed.”

Preventing Misunderstandings: Practical Techniques

Use “mirror summaries” to confirm shared understanding

After you summarize, ask the other side to restate it in their own words. This is one of the most reliable misunderstanding detectors.

Phrase options:

- “Can you sanity‑check my summary? What did I miss?”

- “Just to be safe, how are you describing this agreement to your team?”

If their restatement differs, treat it as a normal coordination issue: “That’s helpful—let’s reconcile those two versions now.”

Separate “decision” from “discussion” items

Meetings often mix brainstorming with commitments. In your recap, label items clearly:

- Decisions: final, executable commitments.

- Open questions: unresolved items with an owner and deadline.

- Parking lot: ideas acknowledged but not agreed.

This prevents someone from later treating a brainstormed idea as a promise.

Make implicit assumptions explicit

Assumptions are where misunderstandings hide. Common assumption categories:

- Capacity: “We assumed you have 10 hours/week available.”

- Access: “We assumed we’ll get admin access to the tool.”

- Data quality: “We assumed the data is complete and stable.”

- Response times: “We assumed feedback within 2 business days.”

Ask: “What are we each assuming that could break this plan?” Then write the assumptions into the agreement as conditions or risks.

Use “if‑then” clauses for predictable failure points

Instead of hoping everything goes smoothly, pre‑agree what happens if it doesn’t.

- “If the dependency is late by more than 3 days, then we move the milestone and notify stakeholders.”

- “If the first deliverable fails acceptance, then we’ll do one revision cycle within 5 business days; additional cycles require reprioritization.”

This reduces emotional escalation later because the response is already agreed.

Control the number of versions and sources of truth

Misunderstandings multiply when different teams reference different documents. Close by naming the source of truth.

- “The signed statement of work is the source of truth; the email recap is a plain‑language summary.”

- “The project brief in the shared folder is the source of truth; changes must be made there and announced in the weekly update.”

Examples: Turning “Agreement” into “Execution”

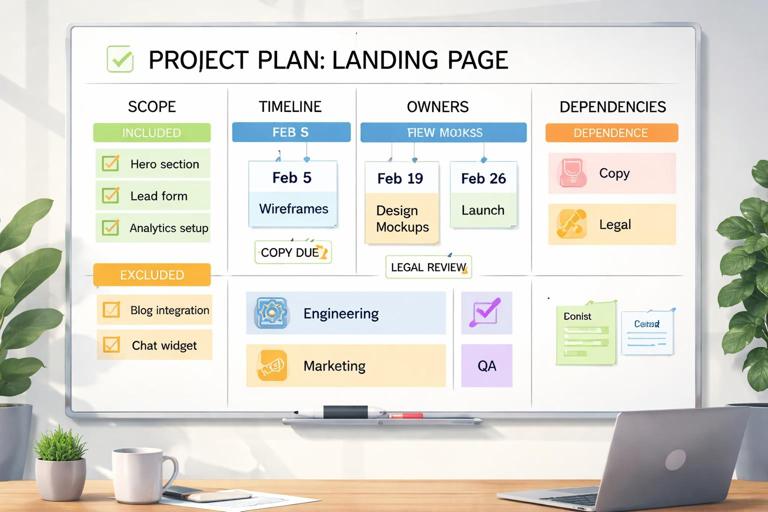

Example 1: Cross‑functional delivery commitment

Vague close: “Engineering will help Marketing launch the new page next month.”

Robust close:

- Deliverable: landing page with form integration and analytics events (list events).

- Scope boundaries: includes desktop + mobile responsive; excludes localization and A/B testing.

- Timeline: design handoff Feb 5; dev complete Feb 19; QA Feb 20–23; launch Feb 26.

- Owners: Eng owner, Marketing owner, QA owner.

- Dependencies: copy finalized by Feb 7; legal disclaimer approved by Feb 9.

- Acceptance: form submits to CRM; events visible in analytics within 30 minutes; page loads under X seconds.

- Change control: new sections after Feb 7 push launch or replace existing sections.

Result: fewer “surprise” requests and fewer disputes about what was promised.

Example 2: Vendor deliverable with review cycles

Misunderstanding risk: review cycles and response times are often assumed, not agreed.

Close elements to include:

- Two design concepts delivered by March 1.

- Client provides consolidated feedback within 3 business days.

- Two revision rounds included; additional rounds billed at a stated rate or require scope swap.

- Final files delivered in specified formats; handoff includes editable source files.

- Acceptance criteria: brand guidelines met; accessibility checks passed; file naming conventions followed.

This prevents the common conflict where one side expects unlimited revisions and the other priced for two.

Handling Last‑Minute Changes Without Reopening Everything

Near the end, someone may introduce a new requirement (“One more thing…”). The goal is to address it without letting the entire agreement become unstable.

A simple triage script

- Name it: “That’s a new requirement compared to what we summarized.”

- Assess impact: “What does it change in timeline, cost, or scope?”

- Offer options: “We can add it by extending the deadline, adding resources, or swapping out another item.”

- Re‑summarize: “So the updated agreement is…”

This keeps the conversation factual and prevents “free” additions that later cause resentment.

When to Use a More Formal Close

Not every agreement needs a contract, but some need more than an email. Increase formality when:

- Multiple departments must execute and handoffs are complex.

- There is meaningful budget, compliance, or security risk.

- Timelines are tight and delays are costly.

- Success depends on measurable performance (SLAs, uptime, response times).

- There is a history of misunderstandings or frequent scope changes.

In these cases, your close may include a signed statement of work, a project charter, a RACI, an SLA, or a change request log. The principle is the same: translate intent into unambiguous commitments and a shared operating system.