What an asthma attack is (and what it is not)

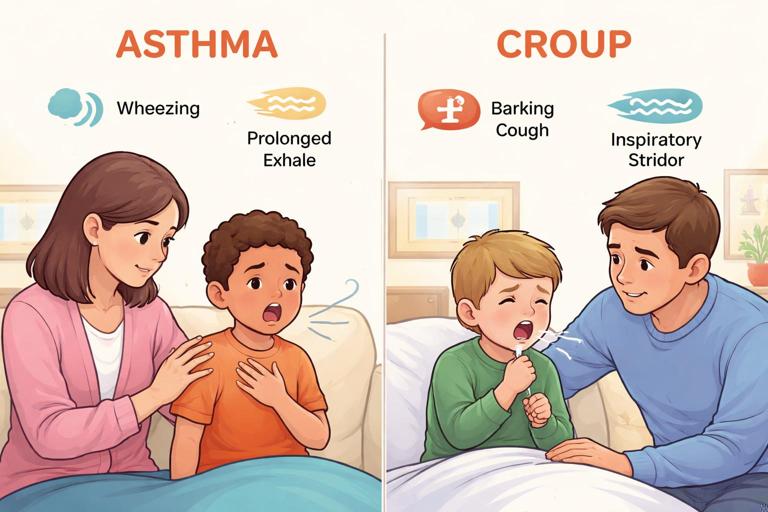

An asthma attack (also called an asthma flare or exacerbation) is a period when the airways in the lungs become narrowed and irritated. Three processes usually happen at the same time: the airway lining swells, the muscles around the airways tighten (bronchospasm), and extra mucus is produced. The result is that air has a harder time moving out of the lungs, which is why wheezing and prolonged breathing out are common.

In infants and children, asthma symptoms can look different from adult asthma. Some children mainly cough, especially at night or with exercise. Others wheeze only during colds. A key first-aid goal is to recognize when breathing is becoming difficult and to support the child in using their prescribed reliever medicine correctly, while watching for signs that the situation is escalating.

Not every episode of noisy breathing is asthma. Upper-airway problems (like croup) often cause a harsh, barking cough and a high-pitched sound when breathing in. Asthma is more often associated with wheeze (a musical sound) and difficulty breathing out. If you are unsure, treat the situation as a breathing emergency and follow the child’s action plan if one exists.

Common triggers in home and school settings

Knowing typical triggers helps you connect the dots quickly and reduce exposure while you support treatment. Triggers vary by child, but common ones include:

- Viral respiratory infections (colds are a very common trigger in children)

- Exercise, especially in cold or dry air

- Allergens (dust mites, pets, pollen, mold)

- Irritants (tobacco smoke, vaping aerosols, strong perfumes, cleaning sprays, air pollution)

- Weather changes and cold air

- Strong emotions or crying (can worsen symptoms once an attack starts)

In a classroom or daycare, triggers may include dusty carpets, art supplies with strong odors, cleaning products used during the day, or outdoor pollen. At home, smoke exposure and pet dander are frequent contributors.

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Recognition: what you can see, hear, and measure

Early signs (mild to moderate flare)

Early recognition allows faster treatment and often prevents escalation. Watch for:

- Coughing that is persistent, especially at night or after running

- Wheeze (may be faint at first)

- Chest tightness (older children may describe “my chest feels tight” or “it’s hard to breathe out”)

- Shortness of breath with activity; the child stops playing to catch their breath

- Faster breathing than usual

- Needing their reliever inhaler more often than usual

Moderate signs (needs prompt reliever support and close monitoring)

- Noticeable work of breathing: ribs or neck muscles pulling in with breaths (retractions)

- Difficulty speaking in full sentences; the child speaks in short phrases

- Wheeze that is clearly audible

- Child prefers sitting upright, leaning forward, or bracing arms (tripod posture)

- Agitation, anxiety, or unusual tiredness

Severe signs (high risk; urgent escalation)

Severe asthma attacks can become life-threatening. Signs include:

- Struggling to breathe, gasping, or very fast breathing

- Unable to speak more than a few words, or cannot cry strongly (in younger children)

- Blue/gray lips or face, or very pale skin

- “Silent chest” (little or no wheeze because airflow is too low to make sound)

- Marked drowsiness, confusion, or collapse

- Head bobbing in infants, or severe chest/neck retractions

If you see severe signs, treat it as an emergency while continuing reliever support if available and prescribed.

Peak flow (if the child uses one)

Some school-age children have a peak flow meter as part of their asthma plan. Peak flow measures how fast they can blow air out. If you are trained and the child is able to cooperate, it can help confirm severity and guide next steps according to their plan. Do not delay treatment to find or use a peak flow meter. If the child is too breathless to perform it correctly, that itself suggests significant severity.

Immediate first-aid priorities during an asthma attack

When a child is having asthma symptoms, your priorities are to reduce distress, support effective medication delivery, and monitor for worsening. Practical steps:

- Stay calm and keep the child calm. Anxiety increases breathing effort and can worsen symptoms.

- Position: sit the child upright. Do not force them to lie down. Let them lean forward if that feels easier.

- Loosen tight clothing around the neck and chest.

- Remove obvious triggers if possible: move away from smoke, strong odors, cold air, or heavy pollen; stop exercise.

- Encourage slow, steady breaths. For older children, coach breathing in through the nose and out through pursed lips if they can.

- Use the child’s prescribed reliever inhaler (usually a short-acting bronchodilator) with a spacer if available.

Avoid giving food or drink during significant breathlessness because it can increase coughing and aspiration risk. Small sips of water may be reasonable if the child is stable and asking, but medication and breathing support come first.

Inhaler and spacer support: making the medicine actually reach the lungs

In real-life emergencies, the biggest problem is often not the medicine but the technique. A metered-dose inhaler (MDI) works best when used with a spacer (and a mask for younger children). The spacer holds the medication cloud so the child can inhale it more effectively, even if they cannot coordinate pressing and breathing in at the same time.

Know the devices you may encounter

- MDI (press-and-breathe inhaler): often used with a spacer; common reliever type.

- Spacer (holding chamber): tube or chamber that attaches to the inhaler; may have a mouthpiece or a face mask.

- Dry powder inhaler (DPI): breath-activated; requires a strong, fast inhale and is harder to use during a severe attack.

- Nebulizer: machine that turns liquid medicine into a mist; sometimes used at home or in clinics.

In first aid, the most practical and widely recommended approach for children is an MDI with a spacer when available.

Step-by-step: MDI with spacer (mouthpiece)

Use these steps for a child who can seal lips around a mouthpiece (often school-age and older):

- 1) Check the medication label: confirm it is the child’s reliever inhaler, not a controller inhaler. If the child has an asthma action plan, follow it.

- 2) Assemble: attach the inhaler to the spacer.

- 3) Shake the inhaler well (about 5–10 seconds) unless the device instructions say otherwise.

- 4) Have the child sit upright and breathe out gently (do not force a long exhale if they are struggling).

- 5) Place the spacer mouthpiece in the mouth with a good seal.

- 6) Press the inhaler once to release one puff into the spacer.

- 7) Have the child breathe in slowly and deeply, then hold their breath for about 5–10 seconds if they can. If they cannot hold, have them take 4–6 normal breaths through the spacer instead.

- 8) Wait about 30–60 seconds between puffs (or follow the child’s plan), then repeat as directed.

- 9) Observe: breathing effort, ability to speak, wheeze, and overall comfort should improve within minutes if the medicine is reaching the lungs.

Practical coaching tip: if you hear a whistling sound from some spacers, it often means the child is inhaling too fast. Coach “slow breath in.”

Step-by-step: MDI with spacer and mask (infants and younger children)

For toddlers and many preschoolers, a mask is safer and more effective than a mouthpiece. Steps:

- 1) Attach inhaler to spacer and attach mask to spacer if it is not already connected.

- 2) Shake the inhaler.

- 3) Place the mask over the child’s nose and mouth with a snug seal. Leaks reduce the dose.

- 4) Press one puff into the spacer.

- 5) Keep the mask in place while the child takes 5–10 normal breaths (count them). Crying reduces effective delivery; calm the child and try again if possible.

- 6) Wait 30–60 seconds between puffs (or per plan) and repeat as directed.

Practical example: in daycare, a 3-year-old starts coughing and wheezing after running outside. The child is frightened and crying. An adult sits the child on their lap facing outward, supports the mask gently but firmly, and counts breaths out loud in a calm voice. After a few puffs, the child’s breathing slows and crying decreases, improving medication delivery further.

If the child has only a dry powder inhaler (DPI)

DPIs require a strong inhale. During an attack, some children cannot generate enough airflow to pull the medicine in. If a DPI is the only available prescribed reliever, help the child follow the device steps carefully: load the dose, seal lips, and inhale quickly and deeply. If the child cannot inhale strongly, treat this as a sign of severity and escalate care according to the action plan or emergency guidance.

Common technique errors and quick fixes

- Not shaking the inhaler: shake before each puff.

- Multiple puffs at once into the spacer: give one puff at a time, then breathe it in.

- Poor mask seal: reposition and check for gaps near the nose.

- Breathing too fast through the spacer: coach slower breaths.

- Child lying down: sit upright.

- Empty inhaler: if the inhaler has a dose counter, check it; if not, assume it may be empty if it has been used frequently and there is no improvement.

Monitoring response: what “improving” looks like

After reliever medicine, improvement often appears within 5–10 minutes. Look for:

- Breathing rate slows and becomes less labored

- Less pulling in at the ribs/neck

- Child can speak more comfortably

- Wheeze reduces (though mild wheeze may persist)

- Child becomes less anxious and can resume calm activity

Do not be reassured by wheeze disappearing if the child still looks very breathless. A “silent chest” can mean airflow is dangerously low.

Escalation: when symptoms are not settling

Escalation means moving from home/school management to urgent medical evaluation. The exact thresholds depend on the child’s asthma action plan, but the following are practical escalation triggers in first aid settings:

Escalate urgently if any severe signs are present

- Blue/gray lips or face, severe pallor

- Exhaustion, drowsiness, confusion, collapse

- Cannot speak/cry effectively

- Very fast breathing with severe retractions or gasping

- “Silent chest” or minimal air movement

Escalate if reliever is not working as expected

- No meaningful improvement within about 10 minutes after correct reliever/spacer use

- Symptoms return quickly after initial improvement

- Reliever is needed again sooner than the child’s plan indicates

- You suspect the inhaler is empty or technique cannot be performed effectively

Escalate if this is a first-time wheeze or diagnosis is uncertain

A child with no known asthma who is wheezing or struggling to breathe needs medical assessment. New wheeze can be asthma, but it can also be infection-related wheeze, inhaled irritant exposure, or other conditions that require evaluation.

Escalate if there are complicating factors

- History of severe asthma attacks, ICU admission, or previous intubation

- Multiple reliever treatments already used today

- Known poor access to medication or no action plan

- Other illness signs such as high fever with lethargy, or chest pain

In school settings, escalation also includes notifying parents/guardians promptly and following the institution’s emergency medication and documentation policies.

Supporting a child while help is on the way

While waiting for medical help or transport, continue supportive care:

- Keep the child upright and warm (but not overheated).

- Stay with the child; do not leave them alone in a bathroom or nurse’s office.

- Continue reliever treatment as directed by the child’s action plan or medical advice if available.

- Observe breathing effort continuously: speaking ability, color, alertness, and retractions.

- Prepare key information: what triggered symptoms, what medicine was given (name, number of puffs, time), and how the child responded.

Practical example: a 10-year-old uses their reliever with a spacer after coughing and wheezing during recess. After several minutes, they still cannot speak full sentences and are hunched forward. Staff keep the child seated upright, continue to follow the child’s written plan for additional puffs, and provide responders with the timeline and observed signs.

Special considerations by age

Infants and toddlers

Very young children may not be diagnosed with asthma yet, but they can still have wheezing episodes. They may show distress through poor feeding, irritability, or unusual quietness. Signs such as head bobbing, grunting, or marked chest retractions are concerning. Medication delivery typically requires a spacer with a mask. Because young children fatigue quickly, have a low threshold to escalate for medical evaluation when breathing effort is significant or persistent.

School-age children

Many can use a spacer mouthpiece and can describe symptoms. They may minimize symptoms to avoid missing activities. Watch for subtle signs: stopping mid-sentence to breathe, refusing to run, or sitting out. Encourage them to follow their action plan early rather than “pushing through.”

Teens

Teens may be embarrassed to use inhalers publicly or may have inconsistent controller use. During an attack, focus on privacy and straightforward coaching: sit upright, use spacer, slow breaths. Ask directly whether they have taken any doses already and whether the inhaler might be empty. If symptoms are severe or not improving, escalate without delay.

What to document and communicate (home, school, sports)

Clear communication prevents repeat dosing errors and helps clinicians. Record and share:

- Time symptoms started and suspected trigger (exercise, cold air, cleaning spray, pet exposure)

- Observed signs (wheeze, retractions, speaking ability, color, level of alertness)

- Medication given: device type, number of puffs/doses, times, and whether spacer/mask was used

- Response to treatment (improved, unchanged, worsened)

- Any barriers (child too distressed to cooperate, inhaler empty, spacer missing)

In schools, follow local policy for incident reporting and for returning medication to the appropriate storage location after the event.

Prevention-focused first aid: reducing the chance of the next attack

Although first aid focuses on the acute event, a caregiver can reduce repeat episodes by addressing practical gaps revealed during the attack:

- Ensure the child has an up-to-date asthma action plan on file at school and at home.

- Confirm the reliever inhaler is within reach during sports and field trips and is not expired or empty.

- Keep a spacer available where the child spends time; many children have better outcomes with a spacer than inhaler alone.

- Identify environmental triggers noticed during the episode (smoke exposure, cleaning sprays, dusty rooms) and reduce them.

- Encourage routine follow-up with the child’s clinician if attacks are frequent, nighttime cough is common, or reliever use is increasing.

Quick reference: Technique checklist for MDI + spacer

- Upright position

- Shake inhaler

- One puff into spacer at a time

- Slow deep breath + hold, OR 4–6 normal breaths

- Wait 30–60 seconds between puffs

- Reassess after 5–10 minutes