Why risk management matters in partnerships

Partnerships create leverage, but they also create shared dependencies. Risk management is the discipline of anticipating where a partnership can harm your business (financially, operationally, legally, or strategically) and designing guardrails so you can capture upside without losing control. In this chapter, we focus on four recurring risk zones that show up in most strategic alliances: exclusivity, revenue share, intellectual property (IP), and data sharing. Each zone has predictable failure modes, and each can be managed with clear definitions, measurable triggers, and practical operating procedures.

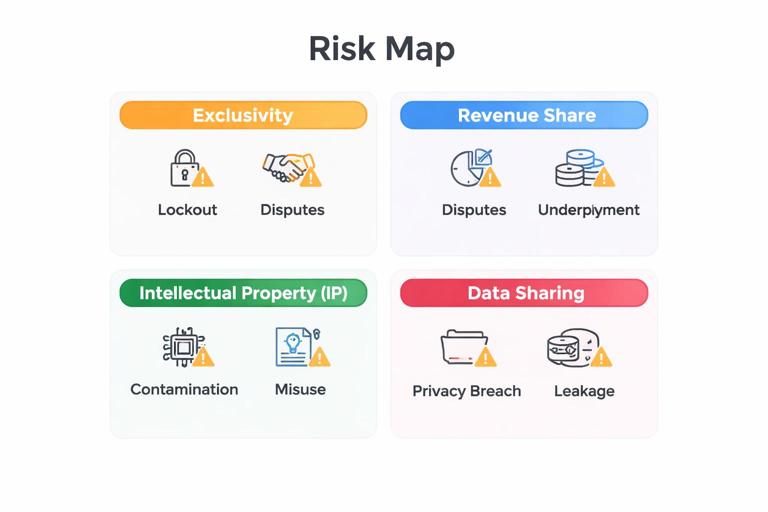

Risk map: the four zones and their typical failure modes

Before drafting clauses or processes, it helps to name the most common ways these areas go wrong. Exclusivity can lock you out of better channels or partners, or prevent you from serving parts of the market. Revenue share can create disputes about what counts as “revenue,” when it is recognized, and what happens with refunds or discounts. IP can be unintentionally transferred, co-owned, or contaminated by the other party’s code or content. Data sharing can violate privacy laws, breach customer trust, or create security exposure. The goal is not to eliminate risk; it is to price it, limit it, and monitor it.

Exclusivity: define it narrowly or pay for it

What exclusivity is (and what it is not)

Exclusivity is a restriction on your ability to partner, sell, market, or distribute in a defined scope. It is not a vague promise to “prioritize” a partner; it is a contractual limitation that can reduce your options. Exclusivity can be mutual or one-way, and it can apply to products, customer segments, geographies, channels, or even specific named accounts. The risk is that you give away future flexibility for current access.

Common exclusivity structures

- Category exclusivity: you won’t partner with competitors in a defined category (often hard to define).

- Channel exclusivity: you won’t sell through other channels (e.g., only through a marketplace).

- Territory exclusivity: a partner is exclusive in a geography (e.g., DACH region).

- Segment exclusivity: exclusive rights for a customer segment (e.g., “mid-market healthcare”).

- Account exclusivity: exclusive rights for a list of named accounts (usually easiest to manage).

Risk controls for exclusivity

The safest exclusivity is narrow, time-bound, and conditional. If exclusivity is broad and unconditional, you are effectively betting your growth on the partner’s execution. To manage this, use three guardrails: scope precision, performance triggers, and exit ramps.

- Scope precision: define the exact products, SKUs, or modules covered; define the exact customer segment; define the exact geography; define the exact channel. Avoid undefined terms like “similar products” or “competitive solutions” unless you attach an exhibit with examples and a change-control process.

- Performance triggers: exclusivity should “earn itself” via measurable commitments (minimum revenue, minimum qualified leads, minimum marketing activities, minimum enablement milestones). If the partner misses targets, exclusivity automatically converts to non-exclusive or narrows in scope.

- Exit ramps: include a short cure period and a clear termination right for underperformance, non-payment, compliance issues, or reputational harm. Also include a transition period so customers are not stranded.

Step-by-step: deciding whether to grant exclusivity

Step 1: Identify what you are giving up. List the top 5 alternative partners or channels you would pursue if you were not exclusive, and estimate their expected value. This becomes your “opportunity cost baseline.”

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Step 2: Define the minimum acceptable compensation. If exclusivity blocks $X of expected value, the partner must compensate through guaranteed minimums, upfront fees, co-marketing funding, or committed resources that plausibly exceed $X.

Step 3: Choose the narrowest workable scope. Prefer named-account or segment exclusivity over category exclusivity. Prefer a single geography over “global.” Prefer a single channel over “all channels.”

Step 4: Add measurable milestones. Convert the partner’s promises into a schedule: enablement completed by date, first campaign by date, pipeline target by date, revenue target by date.

Step 5: Add automatic conversion language. If targets are missed, exclusivity converts to non-exclusive without needing renegotiation. This avoids stalemates.

Step 6: Add a “carve-out list.” Carve out existing customers, inbound leads, strategic accounts you already pursue, affiliates, or other channels you must keep open (e.g., direct enterprise sales).

Practical example: marketplace exclusivity

A SaaS company is offered featured placement on a marketplace if it agrees not to list on competing marketplaces for 12 months. The company narrows exclusivity to “marketplaces serving SMB accounting firms in North America,” carves out direct sales and its own website, and makes exclusivity conditional on the marketplace delivering a minimum number of qualified trials per quarter. If the marketplace misses the target in any quarter, exclusivity becomes non-exclusive for the remainder of the term.

Revenue share: prevent disputes with definitions and auditability

What revenue share really allocates

Revenue share is not just a percentage; it is a set of rules for how money flows, what transactions qualify, and how edge cases are handled. Most revenue-share conflicts come from ambiguity: what counts as “referred,” what counts as “net revenue,” and when the share is earned. Risk management here is about making the calculation deterministic and verifiable.

Key definitions you must lock down

- Qualifying event: what triggers eligibility (e.g., signed contract, paid invoice, activated subscription).

- Attribution window: how long after a referral the partner gets credit (e.g., 90 days, 180 days).

- Net vs gross: whether the share is based on gross receipts or net of taxes, payment processing fees, refunds, chargebacks, discounts, credits, and reseller margins.

- Revenue recognition timing: whether share is paid on cash received or on invoiced amounts.

- Expansion and renewals: whether upsells, cross-sells, renewals, and seat expansions are included, and for how long.

- Refunds and churn: how clawbacks work if a customer cancels or is refunded.

- Bundles: how revenue is allocated when your product is sold as part of a bundle.

Risk controls for revenue share

Use three layers: calculation clarity, reporting cadence, and dispute resolution mechanics.

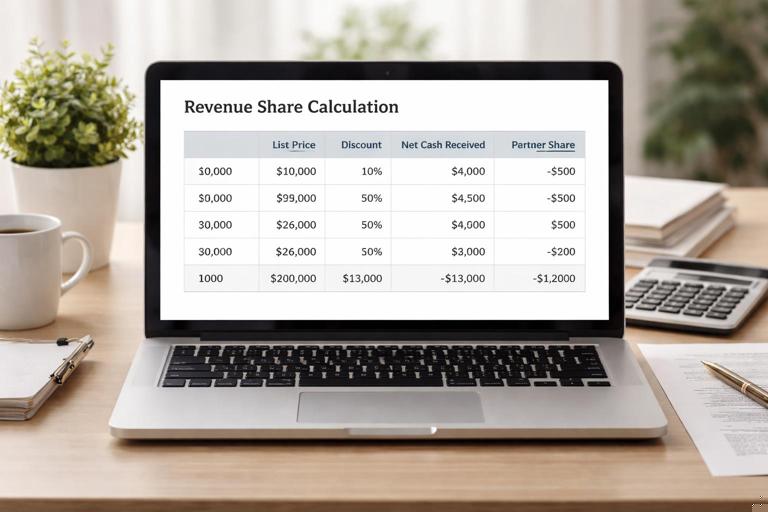

- Calculation clarity: include a worked example table showing how a typical deal is calculated, including discounts and refunds. If a clause cannot be illustrated with numbers, it is likely ambiguous.

- Reporting cadence: define monthly or quarterly statements, the fields included (customer ID, invoice date, amount, discount, net amount, share rate), and the payment timeline.

- Dispute mechanics: define a dispute window (e.g., 30 days after statement), an audit right with reasonable limits, and a process for corrections.

Step-by-step: building a revenue-share model that survives real life

Step 1: Choose the simplest eligible event. “Cash received” is often simpler than “booked revenue” because it avoids recognition debates.

Step 2: Define net revenue explicitly. List allowable deductions in a single clause. Avoid “customary deductions” without a list.

Step 3: Decide how to treat renewals and expansions. A common approach is: partner earns on initial term plus renewals for 12 months, or earns on renewals only if the partner remains active in account management.

Step 4: Add a clawback policy. If a refund occurs within a defined period (e.g., 60 days), the partner’s share is reversed on the next statement.

Step 5: Add a cap or tiering if needed. If margins are thin, use tiered rates based on volume or product line, or cap the share for heavily discounted deals.

Step 6: Make it auditable. Ensure your billing system can produce the statement fields. If you cannot report it, you cannot defend it.

Practical example: co-selling with discounts

You and a partner co-sell to an enterprise customer. The customer negotiates a 30% discount. If the agreement says “10% of revenue,” the partner may expect 10% of list price. To prevent conflict, define revenue share as “10% of net cash received, excluding taxes and refunds,” and include an example: list price $100,000, discount $30,000, net $70,000, partner share $7,000. If a $10,000 refund occurs within 45 days, the next statement deducts $1,000 from the partner’s payout.

IP: protect ownership, avoid contamination, and control derivative works

IP risk in partnerships

Partnerships often involve joint marketing assets, integrations, co-developed features, or shared know-how. IP risk appears when ownership is unclear, when one party’s confidential materials are used beyond the intended scope, or when code and content are combined in ways that create unintended rights. The most expensive IP disputes are not about theft; they are about ambiguity around derivative works and improvements.

Core IP categories to separate

- Background IP: what each party owned before the partnership (software, trademarks, content, patents, processes).

- Foreground IP: what is created during the partnership (integration code, joint collateral, new workflows).

- Improvements: enhancements to a party’s background IP created during the partnership.

- Brand assets: logos, trademarks, product names, and brand guidelines.

Risk controls for IP

Use four controls: ownership clarity, license scope, contribution tracking, and open-source hygiene (for software partnerships).

- Ownership clarity: state that each party retains ownership of its background IP. For foreground IP, choose a default rule: either one party owns it with a license back, or each party owns what it creates. Joint ownership is possible but often creates operational friction because each party may have rights to exploit without accounting, depending on jurisdiction.

- License scope: define purpose, territory, term, sublicensing rights, and whether the license is exclusive or non-exclusive. Most partnership IP licenses should be non-exclusive, limited to the partnership purpose, and revocable upon termination.

- Contribution tracking: for co-created assets, keep a simple register: what was created, by whom, when, and where it is stored. This reduces later disputes.

- Open-source hygiene: if code is exchanged, require that contributions do not introduce restrictive licenses unintentionally, and define who is responsible for scanning and compliance.

Step-by-step: setting IP rules for an integration

Step 1: List integration components. For example: API client library, connector service, UI widgets, documentation, and test suites.

Step 2: Assign ownership per component. A common pattern is: each party owns what it writes; shared documentation is owned by one party with a license to the other.

Step 3: Define permitted use. Example: “Partner may use our SDK solely to build and maintain the integration and to market the integration to mutual customers.”

Step 4: Define derivative works and improvements. If the partner improves your SDK, do you get those improvements back? If yes, specify assignment or a perpetual license to use improvements.

Step 5: Add brand usage rules. Require approval for press releases, define logo placement, and require compliance with brand guidelines.

Step 6: Plan for termination. Specify what happens to code repositories, documentation access, and the right to keep supporting existing customers.

Practical example: co-created playbooks

You and a consulting partner co-create an implementation playbook that includes your proprietary methodology and their templates. If ownership is not defined, both parties may later claim rights to sell the playbook independently. A safer approach is to define the playbook as foreground IP owned by you, with the partner receiving a limited license to use it only when delivering services for mutual customers, and with a restriction against distributing it publicly. Alternatively, each party owns its contributions, and the compiled document is licensed for partnership use only.

Data sharing: minimize, secure, and document lawful purpose

What “data sharing” includes

Data sharing in partnerships can include personal data (names, emails, IP addresses), customer account data (usage metrics, subscription status), and business data (pipeline details, pricing, product roadmaps). The risks include privacy non-compliance, security breaches, unauthorized secondary use, and loss of customer trust. The safest data strategy is to share the minimum necessary data for a defined purpose, for the shortest necessary time, with clear controls.

Data-sharing models and their risk levels

- No transfer (clean room model): each party keeps data; only aggregated insights are exchanged. Lowest risk.

- Tokenized identifiers: share hashed emails or IDs for matching. Moderate risk if re-identification is possible.

- Direct transfer: share identifiable customer data for joint operations. Highest risk; requires strong governance.

Risk controls for data sharing

Use five controls: purpose limitation, data minimization, security standards, retention/deletion, and incident response.

- Purpose limitation: specify exactly why data is shared (e.g., provisioning accounts, joint support, measuring referrals). Prohibit using shared data to market unrelated products or to build competing audiences.

- Data minimization: define the exact fields shared (e.g., company name, admin email, plan tier). If a field is not needed, do not share it.

- Security standards: require encryption in transit and at rest, access controls, least privilege, logging, and secure transfer methods. If applicable, require alignment to a recognized standard (e.g., SOC 2 controls) without overpromising.

- Retention and deletion: define how long data can be kept and how it must be deleted or returned upon termination or upon request.

- Incident response: define notification timelines, cooperation duties, and who bears costs for breaches caused by each party.

Step-by-step: designing a safe data-sharing workflow

Step 1: Write a “data inventory” for the partnership. List each data element, its source, where it will be stored, and who will access it.

Step 2: Map the lawful basis and permissions. Ensure you have customer consent or another lawful basis to share data, and ensure your privacy policy and contracts allow it. If you cannot clearly justify sharing a field, remove it.

Step 3: Choose the lowest-risk model that still works. Start with aggregated reporting or tokenized matching before moving to direct transfer.

Step 4: Implement access controls. Create role-based access, limit to named users, and require multi-factor authentication for systems holding shared data.

Step 5: Define operational procedures. How referrals are submitted, how customer records are updated, how support escalations are handled, and how opt-outs are processed.

Step 6: Test and audit. Run a tabletop exercise for a breach scenario and verify you can produce logs and deletion confirmations.

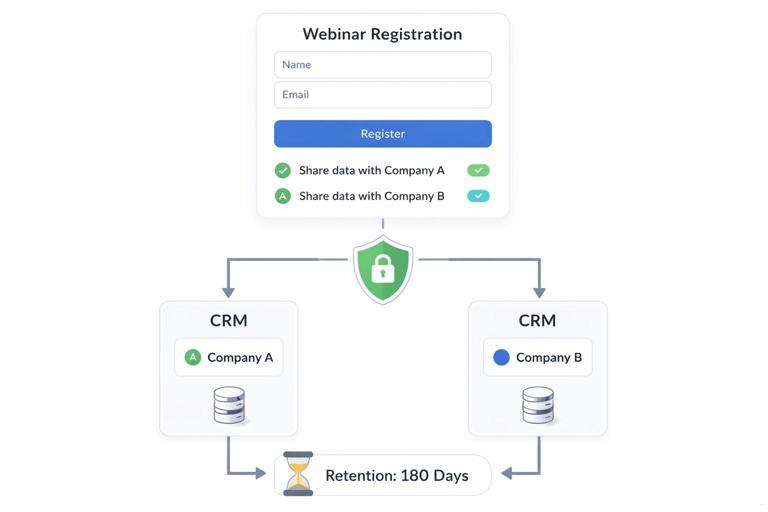

Practical example: joint webinar leads

You run a joint webinar and want to share attendee lists. The lowest-risk approach is to collect explicit opt-in at registration: attendees choose whether to share their details with each company. Then you share only the fields needed for follow-up (name, email, company) and exclude sensitive fields. You also define a retention period (e.g., 180 days) and prohibit uploading the list into broad advertising audiences unless the attendee opted in for marketing.

Putting it together: a partnership risk register you can actually run

What a risk register is

A risk register is a living document that lists key partnership risks, their likelihood and impact, the controls you have in place, and the owner responsible for monitoring them. It turns “legal terms” into operational habits. For the four zones in this chapter, the register should connect contract language to real monitoring signals.

Minimum viable risk register fields

- Risk: e.g., “Exclusivity blocks higher-performing channel.”

- Trigger: e.g., “Partner misses quarterly lead minimum.”

- Control: e.g., “Auto-convert to non-exclusive.”

- Owner: person accountable for monitoring.

- Evidence: report or artifact proving compliance (statements, logs, approvals).

- Review cadence: monthly or quarterly.

Example risk register entries (template)

1) Exclusivity underperformance | Trigger: <80% of quarterly target | Control: convert to non-exclusive | Owner: Partnerships Lead | Evidence: quarterly performance report | Cadence: quarterly

2) Revenue share dispute | Trigger: partner disputes statement | Control: 30-day dispute window + audit process | Owner: Finance Ops | Evidence: payout statements + billing exports | Cadence: monthly

3) IP ownership ambiguity | Trigger: new co-created asset | Control: asset register + ownership rule | Owner: Product Counsel/PM | Evidence: IP register entry + repo links | Cadence: per release

4) Data misuse or over-sharing | Trigger: new data field requested | Control: data inventory approval + minimization | Owner: Security/Privacy | Evidence: approved data map + access logs | Cadence: monthlyNegotiating posture for risk terms: trade risk for value, not for hope

Risk terms are not “legal fine print”; they are business levers. If a partner asks for exclusivity, broader data access, or rights to co-created IP, treat that as a request for additional value. The practical mindset is: every incremental risk you accept should be matched by an incremental commitment you can measure and enforce. When you cannot measure it, you cannot manage it. When you cannot enforce it, you are relying on goodwill rather than governance.