Why Pronunciation, Spacing, and Read-Aloud Accuracy Matter Together

When you read Korean stories aloud, three skills interact at the same time: (1) pronunciation (how each sound is produced), (2) spacing (where word boundaries are written and mentally grouped), and (3) read-aloud accuracy (how faithfully you deliver what is on the page, with correct sounds, rhythm, and phrasing). Many learners treat these as separate topics, but in real reading they are tightly linked. If spacing is misread, pronunciation often changes. If pronunciation is unclear, you may “repair” the sentence by guessing different words. If you read too fast without accuracy checks, small sound changes accumulate and comprehension drops.

This chapter focuses on practical control: producing clear sounds, respecting spacing as meaning, and building a repeatable routine to read mini-fictions aloud accurately.

Pronunciation: Building Reliable Sound Output

1) The core idea: Korean pronunciation is rule-governed, not letter-by-letter

Korean spelling is relatively consistent, but natural pronunciation involves predictable sound changes. Read-aloud accuracy means you apply these changes correctly while still “seeing” the original spelling. Your goal is not to pronounce every letter separately; your goal is to pronounce the intended spoken form while keeping the written form in mind.

Two practical principles help:

Chunk by syllable blocks, then connect across boundaries. Read each syllable clearly, then apply linking rules between syllables.

Continue in our app.- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

Prioritize consonant clarity at the start of syllables and vowel clarity in stressed information. Korean is not stress-timed like English, but important words still need clean vowels to be understood.

2) Tense vs. plain vs. aspirated consonants (accuracy anchor)

One of the most common sources of read-aloud errors is collapsing three-way consonant contrasts into two (or one). Korean distinguishes:

Plain: ㄱ ㄷ ㅂ ㅈ

Aspirated: ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅊ

Tense: ㄲ ㄸ ㅃ ㅉ ㅆ

Practical cues:

Aspirated sounds have a stronger burst of air. Put your hand in front of your mouth and feel the puff (especially with ㅋ, ㅌ, ㅍ, ㅊ).

Tense sounds feel “tight” and crisp, with less air than aspirated. They are not simply “louder.” They are more compressed and firm.

Plain sounds are lighter and can sound closer to English voiced sounds between vowels (e.g., ㄱ can sound like [g] between vowels), but you should still start from the Korean category.

Read-aloud drill (30 seconds): choose one line of text and underline all ㄱ/ㅋ/ㄲ (or ㄷ/ㅌ/ㄸ etc.). Read only those syllables slowly, then read the full line at normal speed.

3) 받침 (final consonants): the “seven sounds” and why they matter

In Korean, many final consonant spellings are pronounced as a smaller set of final sounds. This affects read-aloud accuracy because you must avoid “adding” extra consonants or releasing them too strongly. A practical approach is to remember that 받침 often ends with a closed, unreleased sound.

Common final sound categories (practical grouping):

ㄱ sound: ㄱ, ㄲ, ㅋ (often pronounced like a closed [k̚])

ㄴ sound: ㄴ

ㄷ sound: ㄷ, ㅅ, ㅆ, ㅈ, ㅊ, ㅌ, ㅎ (often pronounced like a closed [t̚])

ㄹ sound: ㄹ

ㅁ sound: ㅁ

ㅂ sound: ㅂ, ㅍ (often pronounced like a closed [p̚])

ㅇ sound: ㅇ

Accuracy tip: if you feel yourself “releasing” the final consonant with extra air (like English final “t”), reduce it. Korean final stops are typically unreleased.

4) Linking and sound change rules you must apply while reading

For story read-aloud, you do not need to memorize every phonology term, but you do need a few high-impact rules that appear constantly.

Rule A: Liaison (연음) when a final consonant meets a vowel

If a syllable ends in a consonant and the next syllable begins with a vowel (often written with ㅇ as placeholder), the consonant moves to the next syllable in pronunciation.

책이 → [채기] (final ㄱ links to 이) 옷을 → [오슬] (final ㅅ links to 을) Step-by-step practice:

Circle 받침 consonants.

Underline the next syllable if it begins with a vowel (ㅇ + vowel).

Read the two syllables as one connected unit.

Rule B: Nasal assimilation (받침 + ㄴ/ㅁ)

When certain final consonants meet ㄴ or ㅁ, the sound often becomes nasal for smoother pronunciation.

국물 → [궁물] 앞니 → [암니] Read-aloud accuracy benefit: this prevents “spelling pronunciation” that sounds stiff and can slow you down.

Rule C: ㄹ interactions (especially ㄴ/ㄹ)

When ㄴ and ㄹ meet, they often become ㄹㄹ in pronunciation.

설날 → [설랄] 신라 → [실라] Practice: mark ㄴ+ㄹ or ㄹ+ㄴ sequences and rehearse them as a single smooth “ll” sound.

Rule D: ㅎ effects (aspiration and weakening)

ㅎ can change neighboring consonants or disappear in fast speech. You will see this often in everyday narration and dialogue.

좋다 → [조타] 많다 → [만타] Accuracy tip: do not force a strong “h” sound; focus on the resulting aspirated consonant.

Spacing (띄어쓰기): Meaning, Rhythm, and Error Prevention

1) The core idea: spacing is not decoration; it is a reading map

Korean spacing helps you identify word units and grammatical relationships quickly. When spacing is misread, you may attach particles to the wrong noun, misidentify a verb, or miss a modifier relationship. In read-aloud, spacing also guides where you naturally pause and how you group sounds.

Two common learner problems:

Over-grouping: reading multiple words as if they were one long word, which causes slurred pronunciation and missed particles.

Over-separating: inserting pauses inside a word group (especially between a noun and its particle), which breaks rhythm and can change meaning emphasis.

2) Practical spacing checkpoints you can apply while reading

Instead of trying to master all spacing rules at once, use checkpoints that directly improve read-aloud accuracy.

Checkpoint A: Noun + particle should be read as one unit

Even though it is spaced as two parts in writing (noun and particle are attached without a space), in speech it behaves like one chunk. The key is: do not pause between them.

가방이 / 문을 / 친구가 Read-aloud drill: lightly tap once per chunk (가방이 = one tap), not per syllable.

Checkpoint B: Verb/adjective + ending is one unit (no internal pause)

Endings carry tense, politeness, and connection. Pausing inside them makes your speech sound hesitant and can confuse listeners.

기다렸어요 / 조용했지만 / 들어가려고 Practice: highlight the stem and endings in different colors, then read them smoothly as one word.

Checkpoint C: Modifier + noun should be grouped (but not rushed)

In stories, descriptive phrases appear frequently. You want a small, natural connection between modifier and noun.

작은 카페 / 어제 산 빵 / 창가에 앉은 사람 Accuracy tip: keep a micro-pause after the noun phrase, not inside it.

Checkpoint D: Numbers, counters, and time expressions are spacing traps

Time and quantity expressions can be read incorrectly if you do not recognize the unit boundaries.

세 시 반 / 두 번 / 3분 만에 / 열한 개 Step-by-step:

Identify the number.

Identify the counter/unit (시, 분, 번, 개, 명, 원, etc.).

Read as one rhythmic block.

3) Spacing and meaning: minimal pairs you should notice

Sometimes spacing changes meaning or at least changes what the reader expects. You do not need to become a spacing expert, but you should train your eyes to notice when spacing creates different groupings.

할 수 있다 (can do) 할수 있다 (nonstandard spacing; can slow reading) 잘 못해요 (often intended as “not good at it,” but standard is usually “잘 못해요/잘 못하다” vs “잘못해요” depending on meaning) 잘못해요 (do it wrong; “incorrectly”) Read-aloud accuracy tip: if you see a form that could be ambiguous, slow down for that phrase and confirm the intended meaning from nearby words. Then commit to one pronunciation and rhythm.

Read-Aloud Accuracy: A Repeatable Method

1) What “accuracy” includes (beyond not making mistakes)

Read-aloud accuracy has three layers:

Text accuracy: you say the correct words in the correct order (no skipping, no substitutions).

Sound accuracy: you apply pronunciation rules naturally (liaison, 받침, assimilation) and keep consonant contrasts clear.

Phrasing accuracy: you group words according to spacing and meaning, using natural pauses at phrase boundaries.

If you only focus on text accuracy, you may sound robotic. If you only focus on sounding natural, you may accidentally change the text. The method below balances both.

2) The 3-pass read-aloud routine (works with any mini-fiction)

Pass 1: Silent scan for “danger zones” (30–60 seconds)

Before speaking, scan the paragraph and mark:

받침 + vowel spots (likely liaison): e.g., 책이, 옷을, 밖에

받침 + ㄴ/ㅁ spots (nasal assimilation): e.g., 국물, 앞니

ㄴ/ㄹ interactions: e.g., 설날, 신라

ㅎ influence: 좋다, 많다, 그렇지

Long noun phrases: modifiers + noun

Numbers/counters: time, money, quantities

This pass prevents mid-sentence stumbles because you pre-decide how you will pronounce tricky transitions.

Pass 2: Slow read with chunking (accuracy-first)

Read aloud slowly, but do not read syllable-by-syllable. Read in chunks guided by spacing and grammar units.

Technique: use “slash chunking” on your text (mentally or with a pencil). Example format:

창가에 앉아서 / 커피를 한 모금 마시고 / 휴대폰을 확인했다. Rules for chunking:

One chunk per phrase (often 3–7 syllables, sometimes longer).

Pause briefly at slashes, not inside chunks.

Within a chunk, apply liaison and assimilation smoothly.

Pass 3: Normal-speed read with “shadow check” (naturalness + control)

Read again at a more natural speed. While reading, do a quick internal “shadow check” at the end of each chunk: did you pronounce the final consonant correctly? Did you link when needed? Did you keep tense consonants crisp?

If you notice an error, do not restart the entire paragraph. Stop at the chunk boundary, repeat only that chunk correctly twice, then continue. This trains recovery and prevents perfectionism from blocking fluency.

Micro-Skills for Cleaner Read-Aloud

1) The “final consonant lock” (받침 closure control)

Many learners add a small vowel after 받침 (e.g., pronouncing “밥” like “바브”). This reduces clarity. Practice locking the final consonant without adding a vowel.

Step-by-step drill:

Say the vowel alone: 바

Add the final consonant closure without extra sound: 밥 (stop cleanly)

Connect to a following vowel word: 밥을 (liaison makes it easier)

밥 / 밥을 / 밥을 먹었다 2) The “two-speed consonant contrast” drill

To keep plain/aspirated/tense contrasts stable, practice at two speeds.

Slow speed: exaggerate the difference (air for aspirated, tightness for tense).

Normal speed: keep the difference but reduce effort.

달 / 탈 / 딸 가 / 카 / 까 Then embed them in short story-like phrases:

달이 떴다 / 탈을 썼다 / 딸이 웃었다 3) Intonation and punctuation: reading like a narrator

Even without acting, punctuation guides accurate phrasing.

Comma (,): small pause, keep pitch moving forward.

Period (.): full stop, reset breath.

Question mark (?): rising or slightly rising intonation depending on question type.

Quotation marks: shift slightly into a “speaker voice” (not necessarily dramatic), and keep the quote as one coherent unit.

Accuracy tip: punctuation pauses should not break a word unit. If a comma appears after a particle or ending, pause after the full chunk, not in the middle of it.

Applied Practice with Mini-Fiction Style Sentences

Practice Set 1: Liaison and spacing chunks

Read each line in three passes (scan → slow chunk → normal). Mark liaison spots and chunk boundaries.

1) 책이 젖어서, 가방에 다시 넣지 않았다. 2) 옷을 갈아입고 밖에 나갔다. 3) 문을 열자마자, 고양이가 먼저 들어왔다. What to focus on:

책이, 옷을: liaison

밖에: 받침 + vowel sound connection in flow

문을: chunk as one unit, no pause between 문-을

Practice Set 2: Nasal assimilation and ㄴ/ㄹ interactions

1) 국물 냄새가 부엌에 가득했다. 2) 앞니가 시려서, 아이스크림을 천천히 먹었다. 3) 설날이라서 가족이 모였다. What to focus on:

국물: [궁물]

앞니: [암니]

설날: [설랄]

Practice Set 3: ㅎ influence and aspirated outcomes

1) 좋다면서도, 표정은 조금 굳어 있었다. 2) 비가 많이 와서 길이 미끄러웠다. 3) 그렇지? 나도 그렇게 생각했어. What to focus on:

좋다: [조타] style outcome

많이: common frequent word; keep it smooth (avoid over-pronouncing ㅎ)

그렇지: natural connected pronunciation, keep rhythm

Self-Checking Without a Teacher: Simple Tools

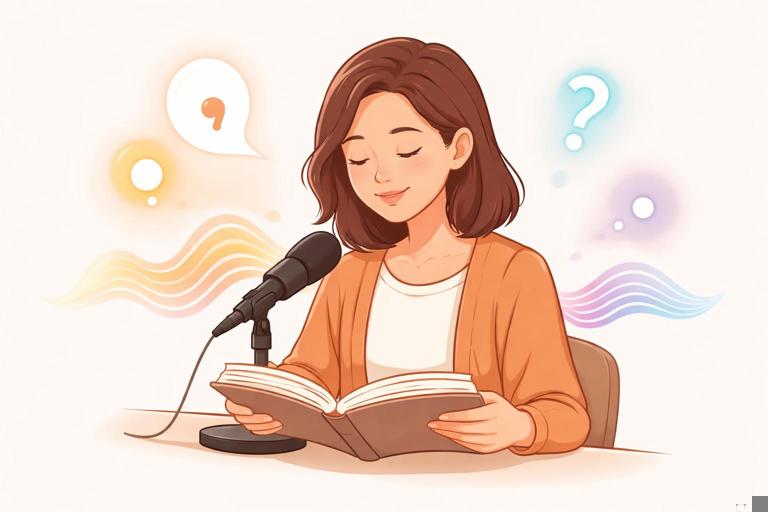

1) The “record and annotate” loop (5 minutes)

To improve read-aloud accuracy, you need feedback. If you do not have a teacher, you can create feedback with a short recording routine.

Step-by-step:

Record yourself reading 4–6 lines (about 20–40 seconds).

Listen once without looking at the text: do you sound smooth? Any unclear parts?

Listen again while looking at the text: mark where you skipped, changed, or hesitated.

Choose only two targets for the next read (e.g., liaison + tense consonants). Do not try to fix everything at once.

Re-record the same lines focusing on those two targets.

2) The “error type label” system

When you notice a mistake, label it. This turns random errors into patterns you can fix.

T = text error (skipped/added/changed word)

P = pronunciation rule error (liaison, assimilation, 받침)

S = spacing/phrasing error (paused in wrong place, wrong grouping)

R = rhythm/speed issue (too fast, monotone, breath problems)

Example annotation:

책이 젖어서, / 가방에 다시 넣지 않았다. → P (책이), S (pause too early) 3) Breath planning for longer sentences

In mini-fictions, sentences can be longer than everyday speech. If you run out of breath, you will distort pronunciation at the end of the sentence. Plan breaths at chunk boundaries.

Step-by-step:

Mark 1–2 safe breath points per sentence (often after a comma or after a completed phrase).

Practice reading to that point with stable volume.

Inhale quietly and continue without rushing the next chunk.

창문을 닫았지만, / 바람 소리가 계속 들렸다.