Why uncertainty changes how you decide

Troubled projects rarely fail because teams cannot make decisions; they fail because teams make decisions as if the situation were certain. Under uncertainty, you do not have complete information, you cannot reliably predict outcomes, and you often have limited time and political capital. The goal is not to “pick the perfect plan,” but to choose a direction that is defensible, reversible where possible, and monitored with explicit stop/go criteria.

Decision-making under uncertainty is the discipline of selecting actions while acknowledging what you do not know, quantifying (or at least ranking) the risks, and designing the next steps to reduce uncertainty quickly. In a rescue context, this means: (1) generating viable options, (2) making tradeoffs explicit, (3) choosing a path using a consistent decision method, and (4) defining objective criteria that trigger continue/pivot/stop decisions.

Core concepts: options, tradeoffs, and decision posture

Options are not “ideas”; they are executable choices

An option is a concrete course of action with a defined scope, timebox, cost range, and expected outcomes. In rescue work, options often include combinations of:

- Stabilize: stop the bleeding (freeze scope, reduce change, harden environments, reduce release frequency temporarily).

- Replan: adjust milestones, re-sequence work, or re-baseline.

- Reduce: cut scope, lower non-critical quality attributes, or defer integrations.

- Invest: add capacity, buy tooling, bring in specialists, or pay down technical debt.

- Change approach: switch delivery model (e.g., from big-bang to incremental), alter architecture boundaries, or change vendor strategy.

- Stop: pause, sunset, or replace the project/product.

Each option should be written so that an executive could approve it without needing to “fill in the blanks.”

Tradeoffs are unavoidable; make them explicit

Under uncertainty, tradeoffs are often hidden behind optimistic language (“We can do both”). A rescue leader surfaces tradeoffs explicitly so stakeholders can choose knowingly. Common tradeoff axes include:

- Listen to the audio with the screen off.

- Earn a certificate upon completion.

- Over 5000 courses for you to explore!

Download the app

- Speed vs. certainty: shipping sooner with higher risk vs. delaying to reduce risk.

- Scope vs. quality: delivering fewer features with higher reliability vs. more features with more defects.

- Cost vs. time: adding spend to accelerate vs. accepting longer timelines.

- Local optimization vs. system stability: pushing one team harder vs. protecting shared services and cross-team dependencies.

- Reversibility vs. commitment: choosing a reversible step (pilot) vs. a hard-to-reverse migration.

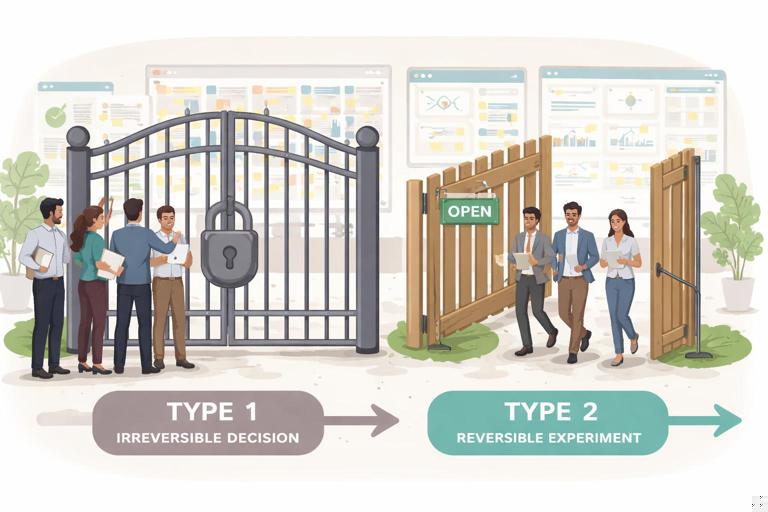

Decision posture: reversible vs. irreversible decisions

Not all decisions deserve the same rigor. A practical posture is to classify decisions into:

- Type 1 (hard to reverse): major vendor switch, platform migration, contractual commitments, public launch dates, layoffs. These require deeper analysis, broader alignment, and stronger stop/go gates.

- Type 2 (easy to reverse): short timeboxed experiments, feature flags, limited pilots, temporary process changes. These should be made quickly with lightweight governance.

In rescue situations, you want to convert as many decisions as possible into Type 2 by designing reversible steps (e.g., pilot one integration rather than migrate everything).

A practical decision framework for rescue situations

Step 1: Define the decision and the decision owner

Write a one-sentence decision statement that includes the action and the time horizon. Example: “Decide whether to proceed with the Q3 release as planned, re-scope to a minimal release, or pause for stabilization, by Friday 5pm.”

Assign a single decision owner (not a committee). Others are contributors. If ownership is unclear, decisions drift and uncertainty increases.

Step 2: Specify objectives and constraints (non-negotiables)

Under uncertainty, teams confuse objectives (“reduce risk”) with constraints (“must comply with regulation”). Separate them:

- Objectives: what you want to optimize (e.g., customer impact, reliability, time-to-value, learning speed).

- Constraints: what you cannot violate (e.g., legal compliance, safety, contractual penalties, data residency, security controls).

Example constraints: “No PII may leave region,” “Must meet audit logging requirements,” “Budget cannot exceed $X this quarter.”

Step 3: List options with “option cards”

Create 3–6 options. Too few options leads to false binaries; too many options causes analysis paralysis. Use a consistent template:

- Name (short and memorable)

- What changes (scope, plan, team, tooling)

- Expected benefits (measurable outcomes)

- Key risks (top 3–5)

- Cost and time range (use ranges, not single numbers)

- Dependencies (teams, vendors, approvals)

- Reversibility (how hard to undo)

- Leading indicators (what you will measure weekly)

Keep each option card to one page. The discipline of fitting it on one page forces clarity.

Step 4: Identify uncertainties and assumptions explicitly

For each option, list assumptions that must be true for the option to succeed. Then mark which assumptions are:

- Known (validated by evidence)

- Unknown but testable quickly (can be validated in days/weeks)

- Unknown and slow/expensive to test (requires major work or external approvals)

Example assumptions: “Vendor API can handle 10x traffic,” “Data migration can be completed with <2 hours downtime,” “Team can sustain two releases per week.”

Turn the most critical unknowns into learning tasks with owners and deadlines (e.g., run a load test, execute a migration rehearsal, complete a security review of a proposed workaround).

Step 5: Evaluate options using a simple scoring model (with ranges)

Use a lightweight multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) approach. Define 5–8 criteria aligned to objectives and constraints. Example criteria:

- Customer impact (near-term)

- Reliability and operational risk

- Time-to-value

- Total cost (next 90 days)

- Team sustainability

- Compliance/security risk

- Reversibility

Assign weights (e.g., 1–5) to reflect what matters most now. Then score each option 1–5 per criterion. Under uncertainty, avoid pretending you know exact scores; instead use ranges (e.g., 2–4) and note why.

Example (simplified): Weights: Customer impact 5, Reliability 5, Time-to-value 4, Cost 3, Team sustainability 4, Reversibility 3 Option A (Ship as planned): Customer 4, Reliability 1-2, Time 4, Cost 3, Team 1, Reversibility 2 Option B (Minimal release + stabilization): Customer 3, Reliability 3-4, Time 3, Cost 3, Team 3, Reversibility 4 Option C (Pause 4 weeks to stabilize): Customer 1-2, Reliability 4-5, Time 1, Cost 2-3, Team 4, Reversibility 3The scoring is not the decision; it is a forcing function to make disagreements visible. If stakeholders disagree on a score, ask: “What evidence would change your score?” That becomes a learning task.

Step 6: Run a pre-mortem to surface hidden failure modes

A pre-mortem assumes the chosen option failed and asks: “What caused the failure?” This is especially useful when optimism bias is strong. Keep it structured:

- Individually write 3–5 failure reasons (5 minutes).

- Share and cluster reasons.

- For the top 5 clusters, define mitigations and monitoring signals.

Example failure modes for a “minimal release” option: hidden integration defects, support team overload, incomplete monitoring, stakeholder backlash due to de-scoped features, compliance gaps in rushed changes.

Step 7: Decide and document the rationale

Document: chosen option, rejected options (and why), key assumptions, and the stop/go criteria. This reduces re-litigation later and protects the team from shifting narratives.

A useful format is a one-page decision record:

- Decision

- Date and owner

- Context (what uncertainty exists)

- Options considered

- Rationale (tradeoffs accepted)

- Risks and mitigations

- Stop/go criteria (with dates)

Designing stop/go criteria that actually work

What stop/go criteria are (and are not)

Stop/go criteria are pre-agreed thresholds that trigger a decision to continue, pivot, or stop. They are not vague intentions (“If things look bad, we’ll revisit”). They are measurable, time-bound, and tied to the project’s critical outcomes.

Good criteria reduce emotional decision-making and prevent sunk-cost fallacy. They also protect stakeholders: everyone knows in advance what “success” looks like for the next stage.

Types of criteria: leading vs. lagging indicators

Use both:

- Leading indicators: early signals that predict outcomes (e.g., defect discovery rate trend, build stability, cycle time, test coverage of critical paths, environment uptime, throughput of integration tests).

- Lagging indicators: outcomes after the fact (e.g., production incident count, customer churn, SLA breaches).

In rescue work, leading indicators matter more because you need early warning to pivot before damage occurs.

Criteria should be tied to decision gates

Define gates such as: “End of week 2,” “After pilot release,” “After migration rehearsal,” “Before contract renewal.” At each gate, you evaluate criteria and decide: continue, adjust, or stop.

Examples of strong stop/go criteria

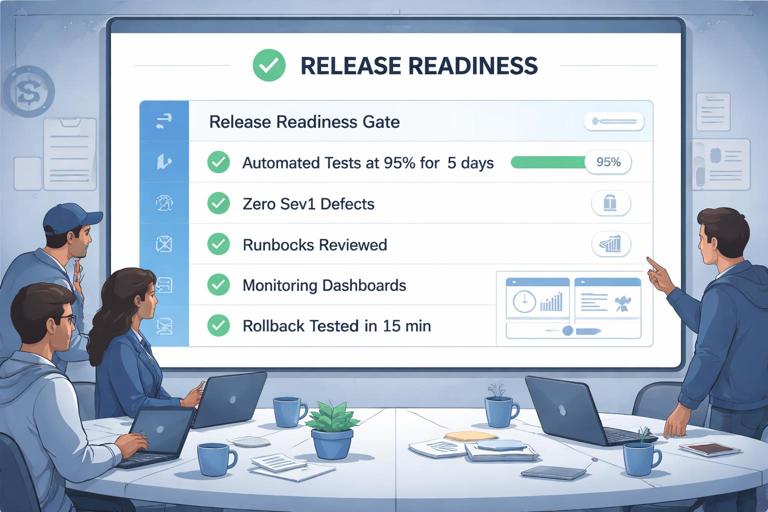

Release readiness gate (go if all are true):

- Critical-path automated tests pass at ≥ 95% for 5 consecutive days.

- No open Severity 1 defects; Severity 2 defects ≤ 3 with documented workarounds.

- On-call runbooks updated and reviewed; monitoring dashboards in place for top 10 failure modes.

- Rollback plan tested in staging with ≤ 15 minutes recovery time.

Stabilization gate (continue stabilization if any are true):

- Mean time to restore service (MTTR) > 60 minutes for two consecutive incidents.

- Change failure rate > 20% over the last 10 deployments.

- Support ticket backlog grows > 15% week-over-week.

Vendor dependency gate (stop/pivot if true):

- Vendor cannot commit to a fix date within 14 days for a blocking defect.

- Vendor performance test results fail to meet minimum throughput in two independent runs.

Budget/timebox gate:

- If the pilot does not demonstrate the target outcome by the end of the 3-week timebox, stop further rollout and reassess options.

Make criteria binary where possible

Ambiguous criteria invite debate. Prefer thresholds and yes/no checks. When a metric is noisy, define a trend requirement (e.g., “improving for 3 consecutive weeks”) rather than a single point.

Common rescue options and their typical tradeoffs

Option: Minimal viable release (MVR) with strict scope control

What it is: Deliver a reduced set of features that achieves a core business outcome, while deferring non-essential work.

Tradeoffs:

- Pros: faster time-to-value, reduces complexity, creates a concrete milestone.

- Cons: stakeholder disappointment, risk of “temporary” deferrals becoming permanent, potential rework if deferred items were foundational.

Stop/go examples: If the MVR cannot pass performance thresholds in staging by week 3, pivot to stabilization before release.

Option: Stabilization sprint(s) before any new scope

What it is: Timeboxed focus on reliability, build health, test automation for critical paths, and operational readiness.

Tradeoffs:

- Pros: reduces incident risk, improves predictability, protects team from burnout.

- Cons: delays visible feature delivery, may be politically hard to justify without clear metrics.

Stop/go examples: If deployment success rate does not improve to ≥ 90% within 2 weeks, escalate for deeper architectural or tooling changes.

Option: Add capacity (people, vendors, parallel teams)

What it is: Increase throughput by adding staff, contractors, or specialist support.

Tradeoffs:

- Pros: can accelerate specific bottlenecks (e.g., testing, DevOps, data migration).

- Cons: onboarding overhead, coordination costs, risk of making the system noisier, budget impact.

Stop/go examples: If added capacity does not increase throughput (e.g., completed stories/week) by an agreed threshold after 3–4 weeks, stop adding and re-evaluate constraints (process, architecture, decision latency).

Option: De-risk via pilot or canary release

What it is: Release to a small segment, one region, or one internal group to validate assumptions.

Tradeoffs:

- Pros: converts unknowns into knowns quickly, limits blast radius.

- Cons: requires tooling and operational maturity (feature flags, monitoring), may slow full rollout.

Stop/go examples: If error rate exceeds X% or support tickets exceed Y/day during pilot, stop rollout and fix before expanding.

Step-by-step: building an “options and criteria” pack in 90 minutes

This is a practical workshop format you can run with key stakeholders to move from debate to decision.

1) Prepare a one-page context brief (10 minutes)

- Decision statement and deadline

- Objectives and constraints

- Top uncertainties (3–7)

2) Generate options (15 minutes)

Facilitate rapid option generation. Require that each option includes a timebox and a measurable outcome. Combine duplicates and remove non-executable ideas.

3) Create option cards (25 minutes)

Split into small groups; each group drafts one option card using the template. Keep ranges for cost/time. Capture assumptions.

4) Score options (15 minutes)

Agree on criteria and weights quickly. Score with ranges. Highlight where scoring disagreements are largest; those are usually the real decision crux.

5) Define stop/go criteria for the top 1–2 options (20 minutes)

For each top option, define:

- 2–4 leading indicators

- 2–3 binary readiness checks

- Gate dates

- Who reviews and who decides at each gate

Write criteria as “If/then” statements to remove ambiguity.

6) Assign learning tasks (5 minutes)

For the top uncertainties, assign owners and deadlines for evidence collection that will be reviewed at the next gate.

Practical examples

Example 1: Integration-heavy release with uncertain performance

Situation: A project depends on three external systems. Performance in test environments is inconsistent, and stakeholders are split between “ship now” and “delay.”

Options:

- Option A: Ship full scope on the planned date with increased monitoring and a rollback plan.

- Option B: Ship a minimal release that uses only one external integration; defer the other two.

- Option C: Run a 2-week performance hardening timebox, then reassess.

Key tradeoff made explicit: Option A optimizes schedule but risks customer-facing incidents; Option B reduces risk but delays some business capabilities; Option C delays all value but may reduce incident probability.

Stop/go criteria for Option B:

- Go to pilot if load test meets p95 latency ≤ 400ms for critical endpoints in two runs.

- Stop rollout if error rate > 1% for 30 minutes during pilot.

- Pivot to Option C if the deferred integrations cannot provide test environments by a specific date.

Example 2: Data migration with uncertain downtime and data quality

Situation: A migration plan assumes a short downtime window, but rehearsals are incomplete and data quality issues are suspected.

Options:

- Option A: Big-bang migration during a weekend window.

- Option B: Phased migration by customer segment with dual-write temporarily.

- Option C: Pause migration, invest in data profiling and reconciliation tooling, then replan.

Stop/go criteria for Option B:

- Proceed to first segment only if reconciliation shows ≥ 99.9% record match on sampled datasets.

- Stop further segments if customer support tickets related to data issues exceed 20/day for 3 consecutive days.

- Pivot to Option C if dual-write introduces unacceptable latency (p95 > 600ms) or operational load (on-call pages > threshold).

Example 3: Team burnout and unpredictable delivery

Situation: Delivery is slipping, and the team is working nights/weekends. Leadership proposes adding more workstreams to “catch up.”

Options:

- Option A: Add parallel workstreams and increase overtime.

- Option B: Reduce scope and enforce sustainable pace; focus on finishing and hardening.

- Option C: Bring in a specialist team for testing/DevOps while core team focuses on feature completion.

Tradeoff made explicit: Option A may accelerate short-term output but increases defect risk and attrition probability; Option B protects sustainability but requires stakeholder acceptance of reduced scope; Option C costs more but may reduce load on the core team.

Stop/go criteria for Option C:

- Continue external support if cycle time decreases by ≥ 20% within 3 weeks.

- Stop and re-evaluate if coordination overhead increases (e.g., blocked work items > threshold) and throughput does not improve.

Anti-patterns to avoid when deciding under uncertainty

“Single-number certainty” estimates

Presenting a single date or cost implies precision you do not have. Use ranges and confidence levels. If stakeholders demand a single number, provide it as a scenario (“best case / most likely / worst case”) and tie it to assumptions.

Deciding based on sunk cost

Past spend is not a reason to continue. The relevant question is: “Given what we know now, is this the best use of the next dollar and the next week?” Stop/go criteria help prevent this bias.

Over-rotating on one stakeholder’s risk tolerance

Some stakeholders are naturally risk-accepting; others are risk-averse. A structured options-and-criteria approach prevents the loudest voice from setting the risk posture by default.

Criteria that measure activity instead of outcomes

“Complete 50 stories” is activity. Prefer outcome-linked measures like “reduce incident rate,” “achieve performance threshold,” or “meet audit requirement.” Activity metrics can be supporting indicators, not primary gates.

Templates you can reuse

Option card template

Name: Summary: (one sentence) What changes: - Scope: - Schedule: - Team/capacity: - Process/tooling: Expected benefits (measurable): - Key risks (top 3-5): - Assumptions (must be true): - Cost/time range: Dependencies: Reversibility (how to undo): Leading indicators (weekly): - Proposed stop/go criteria (gate + thresholds): -Stop/go criteria writing pattern

Gate date/event: GO if: - (binary check or threshold) - PIVOT if: - (threshold indicating plan is not working) - STOP if: - (threshold indicating unacceptable risk/cost) Decision owner: Evidence source: (dashboard, test report, audit sign-off, etc.)